Published online May 7, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i17.4362

Peer-review started: December 20, 2016

First decision: January 13, 2016

Revised: February 9, 2016

Accepted: March 2, 2016

Article in press: March 2, 2016

Published online: May 7, 2016

Processing time: 133 Days and 14.2 Hours

AIM: To examine the association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and general health perception.

METHODS: This cross sectional and prospective follow-up study was performed on a cohort of a sub-sample of the first Israeli national health and nutrition examination survey, with no secondary liver disease or history of alcohol abuse. On the first survey, in 2003-2004, 349 participants were included. In 2009-2010 participants from the baseline survey were invited to participate in a follow-up survey. On both baseline and follow-up surveys the data collected included: self-reported general health perception, physical activity habits, frequency of physician's visits, fatigue impact scale and abdominal ultrasound. Fatty liver was diagnosed by abdominal ultrasonography using standardized criteria and the ratio between the median brightness level of the liver and the right kidney was calculated to determine the Hepato-Renal Index.

RESULTS: Out of 349 eligible participants in the first survey, 213 volunteers participated in the follow-up cohort and were included in the current analysis, NAFLD was diagnosed in 70/213 (32.9%). The prevalence of "very good" self-reported health perception was lower among participants diagnosed with NAFLD compared to those without NAFLD. However, adjustment for BMI attenuated the association (OR = 0.73, 95%CI: 0.36-1.50, P = 0.392). Similar results were observed for the hepato-renal index; it was inversely associated with "very good" health perception but adjustment for BMI attenuated the association. In a full model of multivariate analysis, that included all potential predictors for health perception, NAFLD was not associated with the self-reported general health perception (OR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.40-1.86, P = 0.704). The odds for "very good" self-reported general health perception (compared to "else") increased among men (OR = 2.42, 95%CI: 1.26-4.66, P = 0.008) and those with higher performance of leisure time physical activity (OR = 1.01, 95%CI: 1.00-1.01, P < 0.001, per every minute/week) and decreased with increasing level of BMI (OR = 0.91, 95%CI: 0.84-0.99, P = 0.028, per every kg/m2) and older age (OR = 0.96, 95%CI: 0.93-0.99, P = 0.033, per one year). Current smoking was not associated with health perception (OR = 1.31, 95%CI: 0.54-3.16, P = 0.552). Newly diagnosed (naive) and previously diagnosed (at the first survey, not naive) NAFLD patients did not differ in their self-health perception. The presence of NAFLD at the first survey as compared to normal liver did not predict health perception deterioration at the 7 years follow-up. In terms of health-services utilization, subjects diagnosed with NAFLD had a similar number of physician’s visits (general physicians and specialty consultants) as in the normal liver group. Parameters in the fatigue impact scale were equivalent between the NAFLD and the normal liver groups.

CONCLUSION: Fatty liver without clinically significant liver disease does not have independent impact on self-health perception.

Core tip: In recent years there is overwhelming evidence that non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a major public health concern; the most common chronic liver disorder globally and associated with hepatic and extrahepatic morbidity and mortality. However, this study demonstrates that NAFLD diagnosis among a general population is not independently associated with lower general health perception nor is it associated with higher health care utilization. Moreover, NAFLD does not seem to predict health perception deterioration over the years. These findings imply that in the general population, NAFLD is not considered a disease in the eyes of the NAFLD beholder, probably until an advanced stage.

- Citation: Mlynarsky L, Schlesinger D, Lotan R, Webb M, Halpern Z, Santo E, Shibolet O, Zelber-Sagi S. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is not associated with a lower health perception. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(17): 4362-4372

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i17/4362.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i17.4362

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is defined as fat accumulation in the liver, in the absence of significant alcohol intake. NAFLD is the most common chronic liver disorder globally[1], with a worldwide prevalence estimated from 6.3% to 33% and a median of 20%[2]. Recently, the prevalence of NAFLD was shown to be increasing in developing countries due to adoption of a Western lifestyle, the estimated prevalence of NAFLD varies from 20%-30% in Western countries to 5%-18% in Asia[3].

NAFLD is associated with hepatic and extrahepatic morbidity. Moreover, patients with NAFLD have reduced survival compared with the general population, primarily due to cardiovascular disease followed by malignancy[4-7]. In a Swedish cohort of NAFLD patients with a median follow-up of 27 years, 25% were diagnosed with cirrhosis and 14% with hepatocellular cancer[8]. NAFLD patients do not usually present with symptoms directly attributable to their underlying liver disease[9]. However, some patients report non-specific symptoms, including fatigue or malaise, daytime sleepiness and discomfort in the right upper abdominal quadrant[10]. Fatigue is the most common symptom in NAFLD patients and leads to impaired quality of life[11]. Lifestyle modification is the only established treatment in NAFLD, nevertheless, patients have low level of readiness for change and motivation to adopt a healthier lifestyle (particularly in the area of physical activity). Furthermore, it was shown that the severity of liver disease or liver enzymes elevation, have almost no impact on motivation to change[12].

To date, only a few studies examined quality of life parameters[13,14] or evaluated the utilization of health- care services among NAFLD patients[11,15]. Moreover, self-rated general health perception, a frequently assessed parameter in epidemiological research[16] and a powerful predictor for morbidity and mortality[17], has not been tested in NAFLD patients. Therefore, the current study was aimed to examine the association between NAFLD and general health perception along with fatigue and utilization of health-care services in a sample of a general population screened for NAFLD.

This cross sectional and prospective follow-up study was performed on a cohort of a sub-sample of the first Israeli national health and nutrition examination survey (the MABAT Survey)[18]. On the first survey, MABAT LIVER study, 2003-2004, 349 participants were included. In 2009-2010 participants from the baseline survey were invited to participate in a follow-up survey. No difference was observed between subjects that participated in the follow-up study compared to those who did not participate in any demographic, anthropometric or biochemical parameters as previously reported[19]. In both surveys, individuals with any of the following were excluded from the study: presence of HBsAg or anti-HCV antibodies, fatty liver suspected to be secondary to hepatotoxic drugs, inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease and excessive alcohol consumption (≥ 30 g/d in men or ≥ 20 g/d in women)[2,20].

On both baseline and follow-up surveys the data collected included: measurements of weight, height, and waist circumference following a uniform protocol, interview, biochemical tests, and ultrasound for the diagnosis of NAFLD, all performed on the same day at the Gastroenterology department of the Tel-Aviv Medical Center. All blood samples were drawn at the morning hours after a fast of at least 12 h and assessed by the same laboratory of the Tel-Aviv Medical Center.

A face-to-face interview was carried out in both surveys using a structured questionnaire, assembled by the Ministry of Health and used in national surveys[18], that included demographic details, questions on health status, self-reported general health perception, alcohol consumption, smoking and physical activity habits, frequency of physician’s visits and hospitalization. To avoid report bias, the participants were informed on their US and blood tests results only after filling in the questionnaires.

Fatigue was assessed by the fatigue impact scale (FIS)[21], including 7 questions regarding alertness, decreased work volume, less motivation for physical effort, difficulties in decision making or in thinking process and decreased activity[21]. The fatigue score represents the sum of questions with a positive response. Fatigue as a reason for physical inactivity was assessed by multi-choice question that evaluated the reasons for physical inactivity.

Self-reported general health perception was estimated with one simple question that was highly validated as an indication to general health status and is commonly used in surveys worldwide[17,22,23]. The question was "what is your general health status?" and the answers were: 1- "very good", 2- "good" 3- "not so good" 4- "poor".

Utilization of health service was estimated by a questionnaire assembled by the Israeli Center for Disease Control and used in the Israeli National Health Interview Survey[24]. Numbers of physician’s visits (general physicians and specialty consultants) and hospitalization were assessed by a series of multi-choice questions.

Fatty liver was diagnosed by abdominal ultrasonography using standardized criteria[25]. Ultrasonography was performed in all subjects both at baseline and at follow up with the same equipment (EUB-8500 scanner Hitachi Medical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and by the same experienced radiologist (Webb M) as previously described[26-28]. The radiologist was blinded to the laboratory values and medical history of the participants. During the ultrasonography, a histogram of brightness levels, i.e., a graphical representation of echo intensity within a region of interest was obtained. The ratio between the median brightness level of the liver and the right kidney was calculated to determine the Hepato-Renal Index (HRI). The HRI has been previously demonstrated to be highly reproducible and was validated against liver biopsy[29].

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Tel Aviv medical center and all participants signed an informed consent.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD, while categorical variables are presented in percentage. Univariate analyses were used for the comparison of variable’s distribution between the study groups. To test differences in continuous variables between two groups the independent samples t-test (for normally distributed variables) or the Mann-Whitney U test (if non-parametric tests were required) were performed. To test differences in continuous variables between more than two groups the One-Way ANOVA was performed. To test the differences in categorical variables the Pearson χ2 test was performed. The evaluation of the association between NAFLD and the prevalence of “very good” health perception, adjusting for potential confounders, was performed with multivariate logistic regression analysis, presenting odds ratio (OR) and confidence intervals (CI). The potential confounders included in the multivariate model were: gender, age, body mass index (BMI) and behavioral factors: current smoking and duration of performance of leisure time physical activity in the past year. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Dr. Shira Zelber-Sagi, RD, PhD. Head of nutrition and behavior program, School of Public Health, the University of Haifa and Tel-Aviv Medical Center.

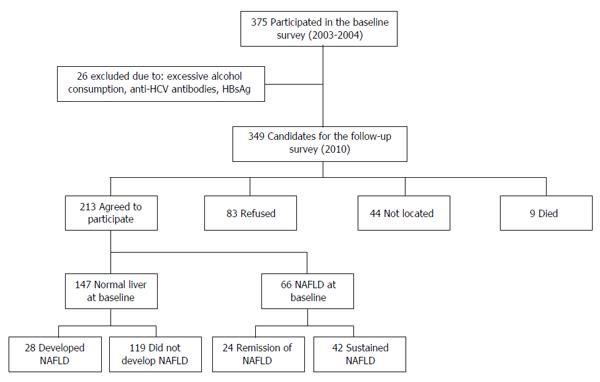

Out of 349 eligible participants in the first survey, 213 volunteers participated in the follow-up cohort and were included in the current analysis (Figure 1), 54% were men, mean age was 57.96 ± 9.58 years and mean BMI was 28.15 ± 4.59 kg/m2. According to abdominal US, NAFLD was diagnosed in 70/213 (32.9%) participants on the follow-up survey. There were no significant age and gender differences between subjects with and without NAFLD. BMI, waist circumference (women and men), serum ALT, blood glucose, serum insulin, HbA1C and triglyceride levels were all significantly higher in the NAFLD group (Table 1).

| Parameter (normal range) | Entire cohort (n = 213) | NAFLD (n = 70) | Normal liver (n = 143) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 57.96 ± 9.58 | 57.87 ± 8.12 | 58.01 ± 10.25 | 0.917 |

| Gender (% males) | 54.0 | 58.6 | 51.7 | 0.348 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (20-25) | 28.15 ± 4.59 | 31.20 ± 4.38 | 26.66 ± 3.92 | < 0.001 |

| Waist circumference men (< 102 cm) | 94.21 ± 10.47 | 98.88 ± 9.01 | 91.66 ± 10.40 | < 0.001 |

| Waist circumference women (< 88 cm) | 83.30 ± 11.01 | 93.49 ± 9.50 | 79.02 ± 8.55 | < 0.001 |

| Current smoker (%) | 17.4 | 25.7 | 13.3 | 0.025 |

| Leisure time physical activity (min/wk) | 96.17 ± 144.97 | 63.00 ± 107.92 | 113.12 ± 158.32 | 0.008 |

| Years of education (%) | 0.333 | |||

| < 12 | 43.4 | 38.0 | 45.9 | |

| 12 | 17.6 | 24.0 | 14.7 | |

| > 12 | 39.0 | 38.0 | 39.4 | |

| ALT (U/L) (5-39) | 24.01 ± 8.60 | 28.31 ± 9.07 | 21.91 ± 7.53 | < 0.001 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) (70-110) | 93.62 ± 25.02 | 101.21 ± 25.62 | 89.90 ± 23.95 | 0.002 |

| Insulin (U/mL) (5-25) | 20.39 ± 9.55 | 24.67 ± 11.22 | 18.33 ± 7.89 | < 0.001 |

| HbA1C (%) (3.9-6.0) | 5.94 ± 0.75 | 6.27 ± 0.78 | 5.78 ± 0.68 | < 0.001 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) (150-200) | 184.45 ± 34.91 | 185.51 ± 38.34 | 183.93 ± 33.24 | 0.757 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) (50-175) | 109.27 ± 55.39 | 133.36 ± 55.01 | 97.48 ± 51.81 | < 0.001 |

| Hepatorenal index | 1.30 ± 0.35 | 1.70 ± 0.31 | 1.09 ± 0.10 | < 0.001 |

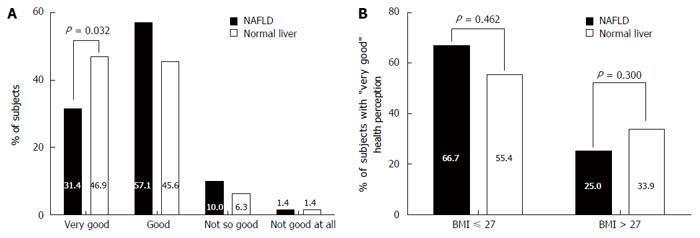

Among the normal liver group, 46.9% reported their general health perception status as “very good”vs 31.4% of the subjects in the NAFLD group (P = 0.032). However, stratification by BMI indicating a clinically significant overweight and above (BMI > 27 kg/m2)[30] eliminated this difference (Figure 2).

In a univariate analysis, the presence of NAFLD was associated with lower odds for a “very good” health perception (compared to “else”) (OR = 0.52, 95%CI: 0.29-0.95, P = 0.033). This negative association remained significant with adjustment for age and gender (OR = 0.46, 95%CI: 0.25-0.87, P = 0.017). However, with farther adjustment for BMI the association with the presence of NAFLD was attenuated (OR = 0.73, 95%CI: 0.36-1.50, P = 0.392) (Figure 3). Similar results were observed for the hepato-renal index; it was inversely associated with "very good" health perception in the crude and in the age and gender adjusted model but not with further adjustment for BMI (Figure 3).

In a full model of multivariate analysis, that included all potential predictors for health perception (gender, age, BMI and behavioral factors: current smoking and duration of performance of leisure time physical activity in the past year), NAFLD was not associated with the self-reported general health perception (OR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.40-1.86, P = 0.704). The odds for "very good" self-reported general health perception (compared to "else") increased among men (OR = 2.42, 95%CI: 1.26-4.66, P = 0.008) and those with higher performance of leisure time physical activity (OR = 1.01, 95%CI: 1.00-1.01, P < 0.001, per every minute/week) and decreased with increasing level of BMI (OR = 0.91, 95%CI: 0.84-0.99, P = 0.028, per every kg/m2) and older age (OR = 0.96, 95%CI: 0.93-0.99, P = 0.033, per one year). Current smoking was not associated with health perception (OR = 1.31, 95%CI: 0.54-3.16, P = 0.552).

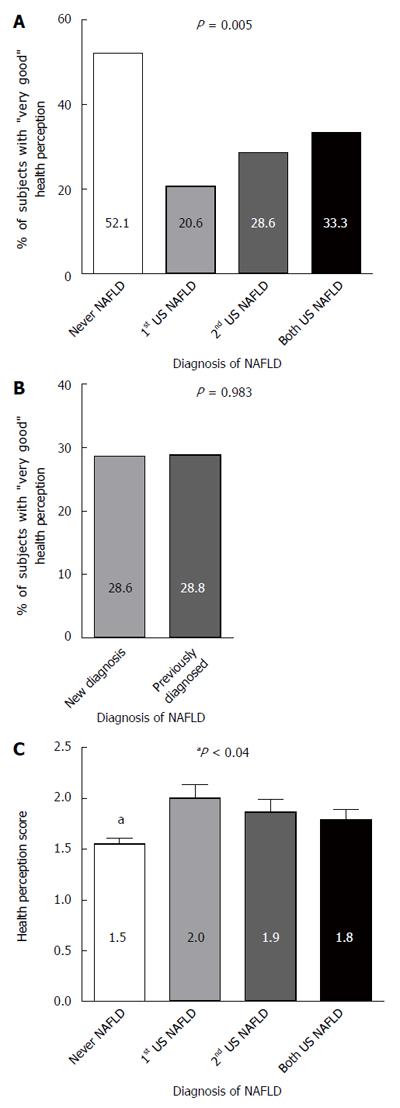

All the participants in the study underwent two abdominal US evaluations with a 7 years interval. Forty-two (19.7%) participants were diagnosed with NAFLD in both US assessments, in 28 (13.1%) NAFLD was observed only in the latter US and in 24 (11.3%) NAFLD was diagnosed only in the first US but not in the second one, 119 (55.9%) participants had a normal liver in both US assessments.

The prevalence of “very good” health perception was higher among the subgroup that was never diagnosed with NAFLD (52.1%) compared to participates who were ever diagnosed with NAFLD during the study (only in the first evaluation, only in the second evaluation, or in both evaluations, 20.6%, 28.6% and 33.3%, respectively, P = 0.005), without significant difference between the “ever NAFLD” groups (Figure 4A). Furthermore, naive (newly diagnosed) and previously diagnosed NAFLD patients (who already knew they have NAFLD) did not differ in their prevalence of "very good" health perception (Figure 4B). Similarly, the average score of general health perception (1 = "very good", 4 = "poor") in patients who were never diagnosed with NAFLD was significantly lower than the score in patients "ever diagnosed" with NAFLD (P < 0.04 for all comparisons), but no significant differences were observed between all "ever diagnosed" with NAFLD groups (Figure 4C).

Among those diagnosed as normal liver at the first evaluation, 61/145 (42.1%) estimated their health as “very good” and among those with NAFLD at the first evaluation, 15/66 (22.7%) had “very good” health perception (P = 0.007). There was no difference between the NAFLD and the normal liver groups (as diagnosed at the first evaluation) in the dynamics of "very good" health perception between the first and follow-up surveys; 75.8% vs 70.3% retained, 9.1% vs 11.7% had a reduction and 15.2% vs 17.9% had improvement in health perception, respectively (P = 0.712).

The total time spent in all types of leisure time physical activity per week was twofold higher among subject without NAFLD as compared to those with NAFLD (113.12 ± 158.32 min/wk vs 63.00 ± 107.92 min/wk, P = 0.008).

In the entire cohort, 70/213 (32.9%) reported avoidance of physical activity. The main reason for avoidance was boredom (37.1%), followed by no available time (20.0%) and fatigue (12.9%). There was no significant difference between subjects with and without NAFLD in the main reason for avoidance from physical activity (P = 0.163). Only 2/26 (7.7%) in the NAFLD group vs 7/44 (15.9%) in the normal liver group reported fatigue as the main reason for avoidance from physical activity with no difference between groups (P = 0.321).

According to the FIS questionnaire, there was no significant difference between the NAFLD and the normal liver groups in any parameter of fatigue (data not shown, P≥ 0.343 for all) including the need to reduce daily activity due to fatigue (20.0% vs 19.6%, respectively, P = 0.781).

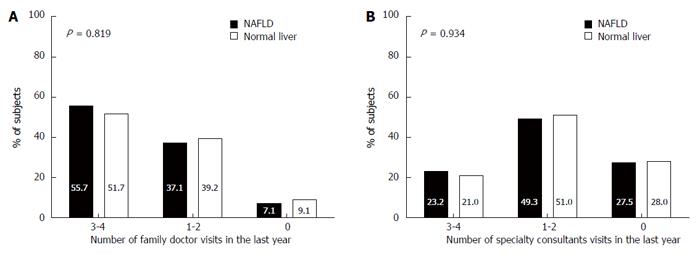

There was no significant difference between subjects with and without NAFLD in the frequency of family doctor visits in the last year (Figure 5A). Furthermore, there was no difference between subjects with and without NAFLD in the frequency of specialty consultants in the last year (Figure 5B), in the occurrence of hospitalization in the last 5 years (28.6% vs 29.4%, respectively, P = 0.904) and in the number of hospitalization events (1.45 ± 0.99 vs 1.55 ± 1.47, respectively, P = 0.789).

NAFLD is emerging as a leading cause for chronic liver disease, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma[2], thus early diagnosis, life style modifications and treatment are essential. The association between NAFLD and general health perception is debatable. Perceived health status is a reflection of both physical and psychological self-perception and has a well-established association with adverse outcomes[31-33]. The question “How is your health in general?” is well validated and a good predictor of future health care utilization and mortality[34,35]. In this study, “very good” health perception was less prevalent among subject with NAFLD compared to subject with normal liver. However, controlling for BMI attenuated the association between both the presence of NAFLD and the amount of liver fat and self-reported health perception. We acknowledge that multicollinearity exists between NAFLD and obesity, the latter was associated with a lower health perception. However, we aimed to learn if NAFLD as a distinct entity is associated with a lower health perception and thus controlled for BMI. To do that, we not only controlled for BMI in a multivariate analysis, but also stratified on it and in both cases it attenuated the association between the presence of NAFLD and self-reported health perception. Moreover, deterioration of "very good" health perception with time could not be predicted by NAFLD. This finding indicates that despite the multiple negative health outcomes of NAFLD, patients don’t feel or think of themselves as sick. This notion is also supported by other findings in our study. First, the NAFLD patients do not utilize more health services as measured by physician visits. Second, even though time spent in leisure time physical activity was lower among NAFLD subjects compared to normal liver controls, fatigue as an explanation for lack of physical activity was evenly reported between the groups. Furthermore, no difference in FIS was noted as well. Lastly, patients with a recent diagnosis of NAFLD (on the follow-up survey), who were unaware of the diagnosis at the time of the interview, had similar health perception as those with “long standing” NAFLD which was detected during the first survey, indicating that patients do not perceive NAFLD as a serious health threat.

Self-rated health has not been previously tested in NAFLD patients, but was tested in relation to diabetes mellitus indicating a greater chance for poor self-rated health among diabetic patients[36]. The difference between the perception of NAFLD and diabetes may stem from the “seniority” of diabetes in terms of disease recognition among physicians and public, the common use in medications in diabetes versus lack of medical treatment in NAFLD and additional diabetes-related complications related to a lower quality of life[37].

Significant positive predictors for “very good” health perception were male gender and regular performance of exercise and negative predictors were BMI and age. Similarly, according to the OECD cross-country comparisons of perceived good health status, in the vast majority of participating countries, men were more likely than women to report good health, and health perception tended to worsen with age[38].

As opposed to the scant data regarding health perception, fatigue is more extensively investigated among NAFLD patients. In a cohort from Newcastle (United Kingdom) 44% of NAFLD patients experienced significant fatigue which was not correlated to thyroid function[39], insulin resistance or severity of liver disease[13]. Fatigue (assessed with FIS) among NAFLD patients was also significantly higher compared with age and sex matched controls[11,13]. The fatigue in NAFLD can be explained by lower blood pressure and autonomic dysfunction, but it may also be that relative hypotension is secondary to fatigue, reflecting the decreased amount of physical activity undertaken by patients who perceive themselves as fatigued[11,14]. Another explanation is excessive daytime sleepiness, the cardinal symptom of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), commonly associated with obesity and NAFLD. OSA is well correlated with insulin resistance, but the correlation to NAFLD is debatable[40,41]. However, in a prospective cohort study, moderate to severe liver steatosis was associated with more severe obstructive sleep apnea. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy for 3 years partially reversed these changes in the majority of patients[42]. Our results may differ from other studies due to different study populations. In the current study the NAFLD subjects were sampled from the general population and not from a selected population of a liver clinic at a medical center.

If indeed fatigue is comparable among NAFLD and normal liver subjects, why do NAFLD subjects exercise less than normal liver subjects? Explanatory factors could be: reduced cardio-respiratory fitness, weight-related arthrosis, psychological factors and a tendency towards a sedentary lifestyle, all correlated with the metabolic syndrome[20,43].

Only few studies evaluated the utilization of health services among NAFLD patients supporting the hypothesis that NAFLD patients have higher utilization of health services compared with the normal liver group[11,15,44]. In a 5-year population-based follow-up study in Germany, the presence of NAFLD, defined by both presence of a hyperechogenic pattern of the liver and elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, was associated with a 26% increase of overall health care costs, after controlling for co-morbidities[45]. The current study results are inconsistent with the limited literature, perhaps since the NAFLD subjects in this study were sampled from the general population, most of them having liver enzymes within the normal range, thus it is very likely that their NAFLD is at a less progressive and symptomatic state compared with NAFLD patients referred for treatment at a medical center which have higher risk for having NASH.

In this study, the utilization of health services was not increased among the NAFLD diagnosed subjects. This finding combined with the equivalent health perception might point towards lack of awareness and understanding that NAFLD is in fact a progressive disease that requires a closer medical surveillance. The misperception of NAFLD as a non-significant disease may also be attributed to the way the health practitioners perceive NAFLD, perhaps not as a disease in itself with potentially severe outcomes, and as a consequence the information they provide to patients and their disease management. Several studies have demonstrated that hepatogastroenterologists[46], primary care practitioners[47] and hospital non-hepatologists specialists[48] do consider NAFLD as a disease and major health problem and follow NAFLD patients, but it is still unclear how firm is the message provided to the patients.

How can this obstacle to patient care be overcome? Health policy approach to improve the patient’s perception and self-management of NAFLD may be an implementation of a “multidisciplinary team approach” in which patients will be followed by physicians, dietitians, psychologists and physical activity supervisors[49]. Furthermore, general practitioners and hepatologists treating NAFLD patients should provide information and refer the patients to appropriate resources about NAFLD implications and treatment and have training in behavioral therapy. Similarly to the treatment approach of other chronic diseases, healthcare providers need to talk with their NAFLD patients more about the broader picture of complications; hepatocellular cancer, increased risk of diabetes, heart attack or stroke, with the message that risk reduction is possible[50]. The 5 A’s model (ask, advise, assess, assist, and arrange) may be useful as a tool to assist clinicians advising NAFLD patients to modify their behavior, assessing their interest in doing so, assisting in their efforts to change, and arranging appropriate follow-up[51].

Our study has several limitations to consider. First, the diagnosis of NAFLD was established by using noninvasive methods of abdominal US and HRI and the histologic diagnosis of inflammation and fibrosis could not be obtained in a sample of the general population. However, with regard to the diagnosis of steatosis, using abdominal US is the most common and acceptable first-line screening procedure for NAFLD in clinical practice and in epidemiological studies[20,52,53].

Second, as mentioned above, the NAFLD subjects were sampled from the general population, thus our sample may not represent the more severe forms of the disease. Last, the utilization of health services was self-reported instead of objectively measured and thus prone to a report bias that may have weakened the observed associations.

In conclusion, NAFLD diagnosis among a general population is not independently associated with lower general health perception nor is it associated with higher health care utilization. Moreover, NAFLD does not seem to predict health perception deterioration over the years. These findings imply that in the general population, NAFLD is not considered a disease in the eyes of the NAFLD beholder, probably until the progressive state.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is defined as fat accumulation in the liver, in the absence of significant alcohol intake. It is the most common chronic liver disorder globally with significant hepatic and extrahepatic morbidity. Moreover, patients with NAFLD have reduced survival compared with the general population, primarily due to cardiovascular disease followed by malignancy.

In recent years there is overwhelming evidence that NAFLD is a major public health concern. However, self-rated general health perception, a frequently assessed parameter in epidemiological research and a powerful predictor for morbidity and mortality, has not been tested in NAFLD patients.

This study demonstrates that NAFLD diagnosis among a general population is not independently associated with lower general health perception nor is it associated with higher health care utilization. Moreover, NAFLD does not seem to predict health perception deterioration over the years. These findings imply that in the general population, NAFLD is not considered a disease in the eyes of the NAFLD beholder, probably until the advanced stage.

More efforts should be directed to establish the acknowledgment of NAFLD as an independent clinical entity with a potentially progressive course. Such a firm and clear message from the treating physician to the patients may promote motivation and adherence to lifestyle changes and a wiser health care utilization for a closer medical surveillance.

Self-reported general health perception was estimated with one simple question that was highly validated as an indication to general health status and is commonly used in surveys worldwide. The question was “what is your general health status?” and the answers were: 1- “very good”, 2- “good” 3- “not so good” 4- “poor”. Hepato-Renal Index (HRI) - during the ultrasonography, a histogram of brightness levels, i.e., a graphical representation of echo intensity within a region of interest is obtained in the liver and in the right kidney. The brightness level for each organ is recorded and the ratio between the median brightness level of the liver and the right kidney cortex is calculated to determine the HRI.

This is a cross sectional study aimed at evaluating the self-rated general health perception in a cohort of 213 subjects form a health survey in Israel. The article is generally well-written and has scientific value, given the high prevalence of NAFLD and the potential implications of its findings in formulating health care policies.

P- Reviewer: Abenavoli L, Carvalho-Filho RJ, Frider B S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Loomba R, Sanyal AJ. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:686-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1127] [Cited by in RCA: 1330] [Article Influence: 110.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Diehl AM, Brunt EM, Cusi K, Charlton M, Sanyal AJ. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology. 2012;55:2005-2023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2413] [Cited by in RCA: 2613] [Article Influence: 201.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Masarone M, Federico A, Abenavoli L, Loguercio C, Persico M. Non alcoholic fatty liver: epidemiology and natural history. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2014;9:126-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ekstedt M, Franzén LE, Mathiesen UL, Thorelius L, Holmqvist M, Bodemar G, Kechagias S. Long-term follow-up of patients with NAFLD and elevated liver enzymes. Hepatology. 2006;44:865-873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1647] [Cited by in RCA: 1708] [Article Influence: 89.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rinella ME. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;313:2263-2273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1508] [Cited by in RCA: 1755] [Article Influence: 175.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Adams LA, Lymp JF, St Sauver J, Sanderson SO, Lindor KD, Feldstein A, Angulo P. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:113-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2092] [Cited by in RCA: 2128] [Article Influence: 106.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Athyros VG, Tziomalos K, Katsiki N, Doumas M, Karagiannis A, Mikhailidis DP. Cardiovascular risk across the histological spectrum and the clinical manifestations of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: An update. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:6820-6834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Önnerhag K, Nilsson PM, Lindgren S. Increased risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer during long-term follow-up of patients with biopsy-proven NAFLD. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:1111-1118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Abd El-Kader SM, El-Den Ashmawy EM. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: The diagnosis and management. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:846-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 10. | Gao X, Fan JG. Diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and related metabolic disorders: consensus statement from the Study Group of Liver and Metabolism, Chinese Society of Endocrinology. J Diabetes. 2013;5:406-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Newton JL. Systemic symptoms in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Dis. 2010;28:214-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Centis E, Moscatiello S, Bugianesi E, Bellentani S, Fracanzani AL, Calugi S, Petta S, Dalle Grave R, Marchesini G. Stage of change and motivation to healthier lifestyle in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2013;58:771-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Newton JL, Jones DE, Henderson E, Kane L, Wilton K, Burt AD, Day CP. Fatigue in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is significant and associates with inactivity and excessive daytime sleepiness but not with liver disease severity or insulin resistance. Gut. 2008;57:807-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Newton JL, Pairman J, Wilton K, Jones DE, Day C. Fatigue and autonomic dysfunction in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Auton Res. 2009;19:319-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ghamar Chehreh ME, Vahedi M, Pourhoseingholi MA, Ashtari S, Khedmat H, Amin M, Zali MR, Alavian SM. Estimation of diagnosis and treatment costs of non-alcoholic Fatty liver disease: a two-year observation. Hepat Mon. 2013;13:e7382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Eriksson I, Undén AL, Elofsson S. Self-rated health. Comparisons between three different measures. Results from a population study. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:326-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Idler EL, Angel RJ. Self-rated health and mortality in the NHANES-I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:446-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 561] [Cited by in RCA: 551] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Keinan-Boker L, Noyman N, Chinich A, Green MS, Nitzan-Kaluski D. Overweight and obesity prevalence in Israel: findings of the first national health and nutrition survey (MABAT). Isr Med Assoc J. 2005;7:219-223. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Zelber-Sagi S, Lotan R, Shlomai A, Webb M, Harrari G, Buch A, Nitzan Kaluski D, Halpern Z, Oren R. Predictors for incidence and remission of NAFLD in the general population during a seven-year prospective follow-up. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1145-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ratziu V, Bellentani S, Cortez-Pinto H, Day C, Marchesini G. A position statement on NAFLD/NASH based on the EASL 2009 special conference. J Hepatol. 2010;53:372-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 723] [Cited by in RCA: 789] [Article Influence: 52.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Fisk JD, Doble SE. Construction and validation of a fatigue impact scale for daily administration (D-FIS). Qual Life Res. 2002;11:263-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Martin LM, Leff M, Calonge N, Garrett C, Nelson DE. Validation of self-reported chronic conditions and health services in a managed care population. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:215-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 418] [Cited by in RCA: 458] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ferraro KF, Wilkinson LR. Alternative Measures of Self-Rated Health for Predicting Mortality Among Older People: Is Past or Future Orientation More Important? Gerontologist. 2015;55:836-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Baron-Epel O, Garty-Sandalon N, Green MS. Patterns of utilization of healthcare services among immigrants to Israel from the former Soviet Union. Harefuah. 2008;147:282-26, 376. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Gore R. Diffuse liver disease. editor Textbook of Gastrointestinal Radiology: Philadelphia: Saunders 1994; 1968-2017. |

| 26. | Zelber-Sagi S, Nitzan-Kaluski D, Goldsmith R, Webb M, Blendis L, Halpern Z, Oren R. Long term nutritional intake and the risk for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a population based study. J Hepatol. 2007;47:711-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 388] [Cited by in RCA: 416] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zelber-Sagi S, Nitzan-Kaluski D, Halpern Z, Oren R. Prevalence of primary non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a population-based study and its association with biochemical and anthropometric measures. Liver Int. 2006;26:856-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zelber-Sagi S, Nitzan-Kaluski D, Halpern Z, Oren R. NAFLD and hyperinsulinemia are major determinants of serum ferritin levels. J Hepatol. 2007;46:700-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Webb M, Yeshua H, Zelber-Sagi S, Santo E, Brazowski E, Halpern Z, Oren R. Diagnostic value of a computerized hepatorenal index for sonographic quantification of liver steatosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:909-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, Hu FB, Hubbard VS, Jakicic JM, Kushner RF. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102-S138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1717] [Cited by in RCA: 2042] [Article Influence: 170.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ashburner JM, Cauley JA, Cawthon P, Ensrud KE, Hochberg MC, Fredman L. Self-ratings of health and change in walking speed over 2 years: results from the caregiver-study of osteoporotic fractures. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:882-889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Brenowitz WD, Hubbard RA, Crane PK, Gray SL, Zaslavsky O, Larson EB. Longitudinal associations between self-rated health and performance-based physical function in a population-based cohort of older adults. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:21-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5455] [Cited by in RCA: 4733] [Article Influence: 169.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | DeSalvo KB, Fan VS, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Predicting mortality and healthcare utilization with a single question. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:1234-1246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 403] [Cited by in RCA: 442] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Miilunpalo S, Vuori I, Oja P, Pasanen M, Urponen H. Self-rated health status as a health measure: the predictive value of self-reported health status on the use of physician services and on mortality in the working-age population. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:517-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 724] [Cited by in RCA: 720] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Molarius A, Janson S. Self-rated health, chronic diseases, and symptoms among middle-aged and elderly men and women. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:364-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Scollan-Koliopoulos M, Bleich D, Rapp KJ, Wong P, Hofmann CJ, Raghuwanshi M. Health-related quality of life, disease severity, and anticipated trajectory of diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2013;39:83-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Scollan-Koliopoulos M; OECD. Health at a Glance 2011: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing 2011; . |

| 39. | Kalaitzakis E. Fatigue in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: is there a role for hypothyroidism. Gut. 2009;58:149-150; author reply 150. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Misra VL, Chalasani N. Obstructive sleep apnea and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: causal association or just a coincidence? Gastroenterology. 2008;134:2178-2179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Ahmed MH, Byrne CD. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and fatty liver: association or causal link? World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4243-4252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Shpirer I, Copel L, Broide E, Elizur A. Continuous positive airway pressure improves sleep apnea associated fatty liver. Lung. 2010;188:301-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Zelber-Sagi S, Ratziu V, Oren R. Nutrition and physical activity in NAFLD: an overview of the epidemiological evidence. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3377-3389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 44. | Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, Pagano G. Meta-analysis: natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests for liver disease severity. Ann Med. 2011;43:617-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 886] [Cited by in RCA: 919] [Article Influence: 65.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Baumeister SE, Völzke H, Marschall P, John U, Schmidt CO, Flessa S, Alte D. Impact of fatty liver disease on health care utilization and costs in a general population: a 5-year observation. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:85-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Ratziu V, Cadranel JF, Serfaty L, Denis J, Renou C, Delassalle P, Bernhardt C, Perlemuter G. A survey of patterns of practice and perception of NAFLD in a large sample of practicing gastroenterologists in France. J Hepatol. 2012;57:376-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Said A, Gagovic V, Malecki K, Givens ML, Nieto FJ. Primary care practitioners survey of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2013;12:758-765. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Bergqvist CJ, Skoien R, Horsfall L, Clouston AD, Jonsson JR, Powell EE. Awareness and opinions of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by hospital specialists. Intern Med J. 2013;43:247-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Bellentani S, Dalle Grave R, Suppini A, Marchesini G. Behavior therapy for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: The need for a multidisciplinary approach. Hepatology. 2008;47:746-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Merz CN, Buse JB, Tuncer D, Twillman GB. Physician attitudes and practices and patient awareness of the cardiovascular complications of diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1877-1881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, Allan J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: an evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:267-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 647] [Cited by in RCA: 645] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Bedogni G, Miglioli L, Masutti F, Tiribelli C, Marchesini G, Bellentani S. Prevalence of and risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the Dionysos nutrition and liver study. Hepatology. 2005;42:44-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 882] [Cited by in RCA: 892] [Article Influence: 44.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Fan JG, Zhu J, Li XJ, Chen L, Li L, Dai F, Li F, Chen SY. Prevalence of and risk factors for fatty liver in a general population of Shanghai, China. J Hepatol. 2005;43:508-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |