Published online Apr 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i14.3785

Peer-review started: December 10, 2015

First decision: January 13, 2016

Revised: January 19, 2016

Accepted: February 20, 2016

Article in press: February 22, 2016

Published online: April 14, 2016

Processing time: 110 Days and 2.1 Hours

AIM: To analyze characteristics and outcome of patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) according to the severity of underlying liver disease.

METHODS: One hundred and sixty-seven adult patients with chronic liver disease and acute deteriorated liver function, defined by jaundice and coagulopathy, were analyzed. Predisposition, type of injury, response, organ failure, and survival were analyzed and compared between patients with non-cirrhosis (type A), cirrhosis (type B) and cirrhosis with previous decompensation (type C).

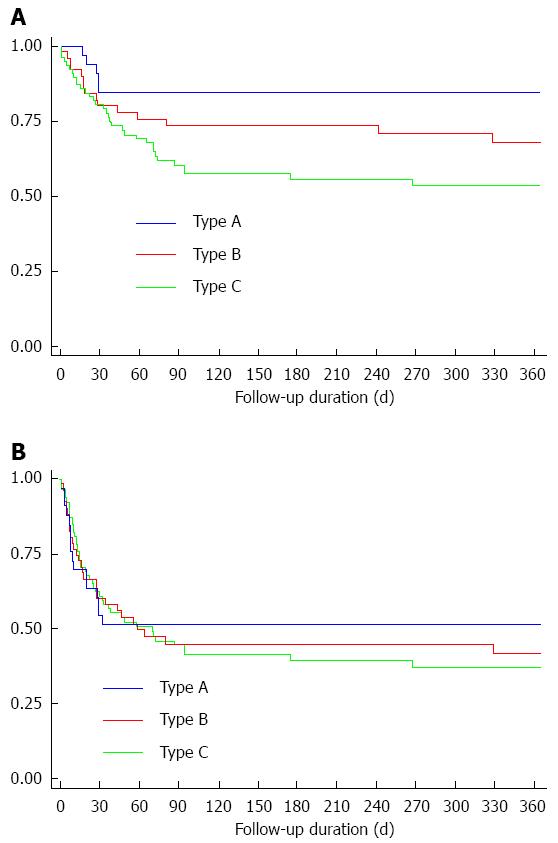

RESULTS: The predisposition was mostly hepatitis B in type A, while it was alcoholic liver disease in types B and C. Injury was mostly hepatic in type A, but was non-hepatic in type C. Liver failure, defined by CLIF-SOFA, was more frequent in types A and B, and circulatory failure was more frequent in type C. The 30-d overall survival rate (85.3%, 81.1% and 83.7% for types A, B and C, respectively, P = 0.31) and the 30-d transplant-free survival rate (55.9%, 65.5% and 62.5% for types A, B and C, respectively P = 0.33) were not different by ACLF subtype, but 1-year overall survival rate were different (85.3%, 71.7% and 58.7% for types A, B and C, respectively, P = 0.02).

CONCLUSION: There were clear differences in predisposition, type of injury, accompanying organ failure and long-term mortality according to spectrum of chronic liver disease, implying classifying subtype according to the severity of underlying liver disease is useful for defining, clarifying and comparing ACLF.

Core tip: Controversy exists over defining acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF). Recently, multimodal ACLF classification that classifies patients into chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis and cirrhosis with previous decompensation has been suggested. We found that the new ACLF classification has clear differences in predisposition, type of injury, accompanying organ failure and long-term outcome by subtype. ACLF patients showed similar high short-term mortality, especially without liver transplantation, according to the subtype, but showed clear difference in the long-term mortality, indicating that the subtyping of ACLF by severity of underlying liver disease is useful.

- Citation: Hong YS, Sinn DH, Gwak GY, Cho J, Kang D, Paik YH, Choi MS, Lee JH, Koh KC, Paik SW. Characteristics and outcomes of chronic liver disease patients with acute deteriorated liver function by severity of underlying liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(14): 3785-3792

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i14/3785.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i14.3785

Patients with either diagnosed or undiagnosed chronic liver disease occasionally present with an acute deterioration of liver function caused by direct or indirect insults to the liver. This event, in general, is termed acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF)[1]. However, because of varied etiology and manifestations, there has been a great heterogeneity in defining the disease and, in fact, a recent systematic review has found more than a dozen definitions for ACLF[2]. Among these, there are 2 mainstream definitions most widely used in clinical settings and research. The Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) consensus introduced an ACLF definition as “an acute hepatic insult manifesting as jaundice (serum bilirubin ≥ 5 mg/dL) and coagulopathy (INR ≥ 1.5), complicated within 4 wk by ascites and/or encephalopathy in patients with previously diagnosed or undiagnosed chronic liver disease/cirrhosis, and is associated with a high 28-d mortality”[3]. The European Association for the Study of the Liver-chronic liver failure (EASL-CLIF) Consortium defined ACLF as acute decompensation of cirrhosis in the form of one or more major complications of liver disease, including ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, gastrointestinal bleeding, and bacterial infection, associated with at least two organ failures with one being renal failure (serum creatinine ≥ 1.5 mg/dL) and high 28-d mortality of greater than 15%[4]. They share a common idea that ACLF is a spectrum of disease with varying severity, characterized by multiple organ failure and high mortality[5-8], with liver transplantation (LT) as the only definitive curative option[9-11]. However, the discordant details between the 2 definitions results in confusion rather than clarification of the situation. In specific, the 2 groups suggest different explanations for the duration of illness, severity of the underlying liver disease, and the type of precipitating events. However, these factors are what essentially define ACLF, because each factor determines the acuteness of event, chronicity of liver disease, and the type of insult, respectively.

To embrace previously suggested definitions and better clarify this condition, Jalan et al[12] recently proposed a new definition and classification for ACLF. They defined ACLF as “a syndrome in patients with chronic liver disease with or without previously diagnosed cirrhosis which is characterized by acute hepatic decompensation resulting in liver failure (jaundice and prolongation of the INR) and one or more extrahepatic organ failures that is associated with increased mortality within a period of 28 d and up to 3 mo from onset”[12]. In their definition, they included any chronic liver disease, regardless of the presence of cirrhosis, and a wide range of precipitating events that could damage liver function either directly or indirectly. Patients with chronic liver disease but without cirrhotic features were categorized as type A. Type B ACLF was a group with previously well-compensated cirrhosis, while those with a history of jaundice and/or complications of portal hypertension were included in type C. However, they admitted that this is a working definition which is only to identify patients from whom to collect data to ultimately reach a validated definition.

Therefore, the aims of this study were to investigate and compare clinical characteristics, including predisposition (etiologies of chronic liver disease), injury (precipitating events), response (manifestations), short and long-term outcomes according to spectrum of chronic liver disease (non-cirrhosis, cirrhosis and cirrhosis with previous decompensation), thereby, to determine relevance of subtyping ACLF by severity of underlying disease for future practice and research.

This is a retrospective cohort study conducted by using electronic medical records of ACLF patients who visited Samsung Medical Center between January 1, 2011 and June 30, 2014. We included patients 18 years or older and with deteriorated liver function, defined as jaundice (serum bilirubin ≥ 5 mg/dL) and coagulopathy (PT INR ≥ 1.5). A total of 268 patients were identified, and we excluded 101 patients due to the following reason: acute liver failure patients without underlying chronic liver disease (n = 91), patients with chronic hepatic decompensation (n = 9) (chronic liver failure without acute component), and patients who were on warfarin (n = 6). Chronic liver disease was defined when there was evidence of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection by reviewing serologic markers and history, history of significant alcohol intake, history of chronic abnormality in liver profiles with serologic evidence of autoimmune liver disease, and/or radiological evidence of cirrhosis. The final study sample includes 167 patients. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center. Because the study is based on the retrospective analysis of existing administrative and clinical data, the requirement of obtaining informed patient consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center. Patient records/information was anonymized and de-identified prior to analysis.

Data on etiologies and severity of underlying liver disease at the time of diagnosis were evaluated. Acute precipitating events, major presenting complications and the presence of organ failure and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) were assessed. Additionally, laboratory measurements including complete blood count (CBC), liver function tests, renal function tests, coagulation profile and culture tests were reviewed. Information on LT, mortality and cause of death was collected until a year after the enrollment.

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD), chronic hepatitis B, chronic hepatitis C, autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), Wilson’s disease, biliary cirrhosis, Budd-Chiari syndrome, and cryptogenic liver cirrhosis were regarded as chronic liver diseases. Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis were confirmed by a thorough review of available previous medical records: biochemical analysis, ultrasonography, abdomen computed tomography (CT), and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Cirrhosis was considered to be present if thrombocytopenia (platelet < 150 × 103/μL), splenomegaly, ascites (by cross sectional images), varices (by EGD, cross-sectional images, or history of variceal bleeding), and cirrhotic features of the liver (nodular surface or caudate lobe hypertrophy) in cross-sectional images were present[13]. When the findings were compatible with chronic liver disease without any features of liver cirrhosis, patients were designated type A. If patients had a previous history of jaundice and/or complications of portal hypertension such as variceal bleeding, ascites or hepatic encephalopathy, these patients were classified as type C of ACLF. Well-compensated liver cirrhosis patients were included in type B.

As possible injury, hepatic insults included reactivation of HBV, alcohol ingestion, superinfection by hepatitis A virus (HAV), toxic hepatitis, and AIH flare. Bacterial infection/sepsis, variceal bleeding, and non-variceal bleeding were regarded as extrahepatic insults. Alcohol consumption was considered as the most probable precipitating etiology when active alcohol consumption was documented within the last 4 wk and there was no other apparent cause of the acute event. Positive anti-HAV IgM by ELISA confirmed acute HAV infection. In addition, bacterial infection/sepsis was considered as an acute insult in case of definite evidence of infection, such as positive cultures of blood, ascites, urine and sputum and/or when clinically suspected. If patients had multiple injuries (e.g., HBV reactivation and variceal bleeding) and if it is difficult to differentiate an initial one, both of them were considered. Injury was categorized as unknown when all other possible causes were not matched.

The Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, SIRS, and organ failure were investigated[14]. The presence of each organ failure, as well as the number of organ failures was evaluated at the initial visit (baseline). Type of organ failure was categorized into none, hepatic/coagulation, and extrahepatic ± hepatic/coagulation. Extrahepatic organ failure was defined for renal, cerebral, circulatory and respiratory organ failure. Organ failure was defined according to the EASL-CLIF score[4].

The primary end-point was 30-d survival. Secondary end-point was 30-d transplant free survival, 1-year overall survival and 1-year transplant free survival. With transplant free survival, transplant was considered as end point (failure). Patient survival was assessed for 365 d after the initial visit. Patients who were lost to follow-up without reaching the end point were classified as censored cases.

Means ± SD were used for describing continuous outcomes, and analysis of variance was applied to compare the means of the different ACLF groups. In addition, Bonferroni’s method was used as a post-hoc test for group comparison. χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were employed as needed for categorical variables. The Kaplan-Meier method was applied for estimating the survival rates, and the differences of the survival were compared using a log-rank test. We also obtained Bonferroni adjusted P-values to compensate multiple testing procedures. P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Comparison of baseline characteristics is shown in Table 1. The etiology of predisposing liver diseases was significantly different according to the ACLF types. Hepatitis B was the most common etiology in type A, while ALD was more common in type B and type C. AIH was more common in type A. Interestingly, except for unknown cases, all ACLF of type A were caused by injury directed at the liver. HBV flare was the most common precipitating event in type A. On the other hand, extrahepatic insults such as bacterial infection and bleeding episodes were more responsible for type C. Type B were in-between type A and type C. The specific injuries (precipitating events) are shown in Table 2. MELD score and SIRS at diagnosis were comparable among the types. In terms of organ failure, defined by the CLIF-SOFA system, the extrahepatic failure was more frequent in type C than type A, and hepatic/coagulation failure was more frequent in types A and B than type C.

| Type A (n = 34) | Type B (n = 53) | Type C (n = 80) | P value | |

| Age (yr)c | 51.9 ± 10.3 | 54.0 ± 10.3 | 58.0 ± 11.1 | 0.010 |

| Male | 20 (58.8) | 32 (60.4) | 59 (73.8) | 0.159 |

| Predisposition | ||||

| HBVc | 21 (61.8) | 19 (35.9) | 28 (35.0) | 0.020 |

| Alcoholac | 4 (11.8) | 25 (47.2) | 33 (41.3) | 0.001 |

| HCV | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (7.5) | 0.051 |

| Autoimmunec | 6 (17.7) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (2.5) | 0.008 |

| Others | 3 (8.8) | 7 (13.2) | 11 (13.8) | 0.827 |

| Injury | ||||

| Hepaticace | 30 (88.2) | 31 (58.5) | 9 (11.3) | < 0.001 |

| Extrahepaticace | 0 (0.0) | 13 (24.5) | 44 (55.0) | < 0.001 |

| Unknowne | 4 (11.8) | 4 (7.6) | 23 (28.8) | 0.005 |

| Both (hepatic + extrahepatic) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (9.4) | 4 (5.0) | 0.165 |

| Response | ||||

| MELD score | 29 ± 8.3 | 27 ± 5.7 | 26 ± 6.3 | 0.137 |

| SIRS | 9 (26.5) | 19 (35.9) | 30 (37.5) | 0.516 |

| Organ failures by CLIF-SOFA | ||||

| Type of organ failure | ||||

| Nonee | 8 (23.5) | 8 (15.1) | 28 (35.0) | 0.035 |

| Hepatic/coagulationce | 19 (55.9) | 34 (64.2) | 21 (26.3) | 0.000 |

| Extrahepaticc | 7 (20.6) | 11 (20.8) | 31 (38.8) | 0.038 |

| Specific organ type | ||||

| Hepaticce | 26 (76.5) | 42 (79.3) | 28 (35.0) | < 0.001 |

| Coagulation | 10 (29.4) | 11 (20.8) | 21 (26.3) | 0.630 |

| Renal | 7 (20.6) | 5 (9.4) | 17 (21.3) | 0.182 |

| Cerebral | 2 (5.9) | 4 (7.6) | 11 (13.8) | 0.418 |

| Circulatoryce | 1 (2.9) | 4 (7.6) | 16 (20.0) | 0.021 |

| Respiratory | 2 (5.9) | 1 (1.9) | 4 (5.0) | 0.679 |

| Number of organ failure | ||||

| Nonee | 8 (23.5) | 8 (15.1) | 28 (35.0) | 0.035 |

| Onee | 13 (38.2) | 29 (54.7) | 26 (32.5) | 0.036 |

| ≥ 2 | 13 (38.2) | 16 (30.2) | 26 (32.5) | 0.733 |

| Type A | Type B | Type C | P value | |

| HBV flareace | 17 (50.0) | 11 (20.8) | 4 (5.0) | < 0.001 |

| Alcoholae | 3 (8.8) | 19 (35.9) | 6 (7.5) | < 0.001 |

| HAV | 3 (8.8) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (1.3) | 0.130 |

| Toxine | 5 (14.7) | 9 (17.0) | 3 (3.8) | 0.021 |

| AIH flarec | 7 (20.6) | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | < 0.001 |

| Infectionac | 0 (0.0) | 13 (24.5) | 32 (40.0) | < 0.001 |

| Varix bleeding | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.7) | 11 (13.8) | 0.035 |

| Other bleeding | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.8) | 6 (7.5) | 0.215 |

| Unknowne | 4 (11.8) | 4 (7.6) | 23 (28.8) | 0.005 |

At 30 d, the overall survival rate and the transplant-free survival rate were 83.2% and 61.1%, respectively. At 1 year, the overall survival rate and the transplant-free survival rate were 68.3% and 46.7%, respectively. The most common cause of death was infection (52.8%), followed by bleeding (20.8%). During the follow-up period, 44 patients (12, 16 and 16 in types A, B, and C, respectively) received LT.

According to each ACLF type, the overall 30-d survival rate (85.3%, 81.1% and 83.7% for type A, B and C, respectively, P = 0.31; Figure 1A) and transplant-free survival rate at 30 d (55.9%, 65.5% and 62.5% for type A, B and C, respectively, P = 0.33; Figure 1B) were not different among the types. However, the overall 1-year survival was significantly higher in type A (85.3%), as compared to types B (71.7%) and C (58.7%) (P = 0.02; Figure 1A). All mortality occurred within 30 d in type A, but mortality continued to occur after 30 d in types B and C. Transplant-free survival rate at 1-year was also lower in type C, as compared to types A and B; but the difference was not statistically significant (52.9%, 51.7% and 34.8% for type A, B and C, respectively, P = 0.86; Figure 1B).

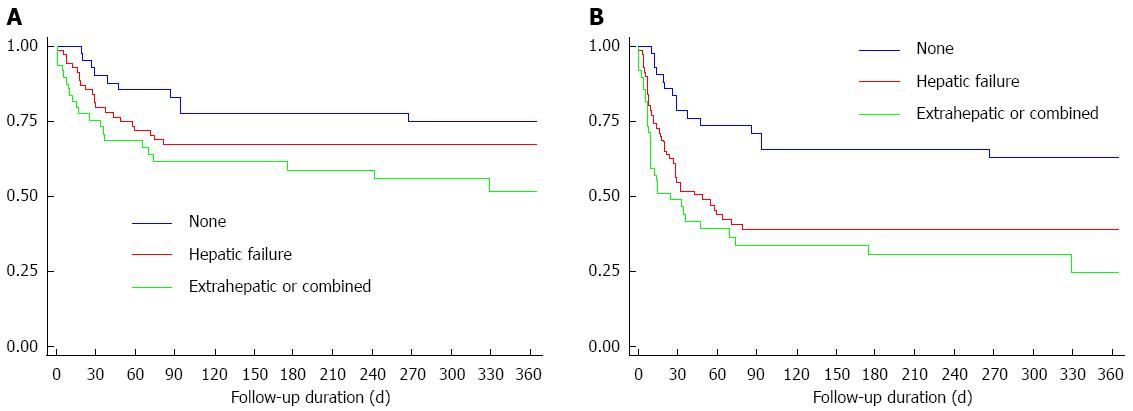

Among 167 patients, 49 patients (29.3%) had extrahepatic organ failures with or without hepatic/coagulation failure, 74 patients (44.3%) had hepatic/coagulation failure, and 44 patients (26.3%) showed no organ failure defined by EASL-CLIF. The 30-d and 1-year overall survival rate was 55.9% and 51.6% for patients with extrahepatic organ failures, 79.6% and 67.4% for hepatic and/or coagulation organ failure, and 90.0% and 74.5% for patients without organ failure, respectively (Figure 2A). The 30-d and 1-year transplant free survival rate was 48.9% and 19.6% for patients with extrahepatic organ failures, 54.9% and 37.6% for hepatic and/or coagulation organ failure, and 78.7% and 56.7% for patients without organ failure (Figure 2B).

The 30-d and 1-year overall survival rate was 74.8% and 56.2% for patients without LT, while it was 95.9% and 83.5% for patients with LT. The 30-d survival rate was higher in patients with LT in all ACLF types, although the difference was statistically significant only in type C (Type A: 92.3% vs 80.0%, P = 0.37; Type B: 93.7% vs 76.7%, P = 0.14; type C: 100% vs 78.7%, P = 0.029) and 1-year survival rate (Type A: 92.3% vs 80.0%, P = 0.37; Type B: 80.2% vs 62.4%, P = 0.18; Type C: 80.0% vs 42.1%, P = 0.007).

ACLF, by in the simplest term, is “abrupt hepatic decompensation in patients with chronic liver disease”[12]. Moreover, ACLF is usually defined as a condition wherein patients are at significantly increased risk for mortality, with improvement in survival with LT[12]. There is controversy regarding what constitutes a chronic liver disease. APASL includes non-cirrhotic chronic liver disease/cirrhosis, but not decompensated cirrhosis to define chronic liver disease[3,15] whereas EASL-AASLD includes only cirrhosis, either compensated or decompensated[4], The newly proposed ACLF definition includes all spectrum of chronic liver disease and categorizes them as type A (non-cirrhotic), type B (cirrhosis), and type C (decompensated cirrhosis)[12]. The present study included all stages of chronic liver disease patients with acute deteriorated liver function, defined by jaundice (serum bilirubin ≥ 5 mg/dL) and coagulopathy (PT INR ≥ 1.5). All types of patients showed comparably high short-term mortality, and improved survival with LT. The overall survival was significantly better for patients who received LT, and the survival benefit by LT was most prominent in type C (1-year survival rate: 80.0% vs 42.1% for with and without LT, P = 0.007). Thus, our finding support that ACLF can be defined for all spectrum of chronic liver disease (i.e., non-cirrhotic to decompensated cirrhosis).

ACLF, by definition, also implies acute insult that leads to acute deterioration of liver function[3]. For example, superimposed viral hepatitis in chronic liver disease is a well-known injury to put patients at higher risk for acute deterioration of liver function[16]. Bacterial infection or sepsis is also a major risk factor for adverse event in cirrhosis patients[17,18]. Acute insults that lead to ACLF can be categorized as hepatotrophic insult (viral hepatitis, alcohol, drug, autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, etc.) and non-hepatotrophic insults (infection, surgery, bleeding, etc.)[3]. Because ACLF is a potentially reversible disease[1], it is very important to identify acute insults, and have immediate intervention (e.g., antiviral therapy for hepatitis B, treatment for infection). Importantly, except for few causes where specific injury was uncertain, all type A injuries were hepatotrophic injury (Table 1). In contrast, type C mostly comprised non-hepatotrophic insults, although hepatotrophic insults were observed as well. Type B was in between type A and type C. Organ failure rate was similar in terms of renal, cerebral, coagulation and respiratory failure by ACLF type, but hepatic failure was less frequent and circulatory failure was more frequent in type C (Table 1). Higher rate of circulatory failure in decompensated cirrhosis could be explained by circulatory dysfunction observed in cirrhosis[19]. Differences in injury (precipitating insult) and response (organ failure rates) by ACLF types provide a rationale to categorize ACLF as type A, B and C, which is also helpful in searching potential injury and planning specific intervention in patients with ACLF. It is also noteworthy that type B and type C were still at risk for mortality after 30 d, leading to a decreased 1-year survival compared to type A. This also provides a rationale to categorize patients who experienced ACLF, as different long-term prognosis is expected.

The presence of “one or more extrahepatic organ failure” was suggested to define ACLF in the newly proposed ACLF definition[12]. However, question remains whether “extrahepatic organ failures” are mandatory to define ACLF. ACLF, by its simplest meaning, does not include “extrahepatic organ failures”. The purpose of including “extrahepatic organ failures” in the ACLF definition is to define the population at high risk for mortality. Our data did indeed show extremely poor short-term survival for patients with extrahepatic organ failures defined by CLIF-SOFA (55.9% and 48.9% for overall and transplant free 30-d survival), and good short-term survival for patients without any organ failures defined by CLIF-SOFA (90.0% and 78.7% for overall and transplant free 30-d survival). This is consistent with previous findings that extrahepatic organ failures are an important factor for survival in ACLF[20]. The association between organ failure and poorer prognosis is supported by numerous studies[4,11,21-26]. However, patients with only hepatic/coagulation failure also showed high short-term mortality (79.6% and 54.9% for 30-d overall and transplant-free survival). Furthermore, mortality rate exceeding 15% without LT (90.0% and 79.7% for 30-d overall and transplant-free survival) even for patients without any organ failures defined by CLIF-SOFA. Short-term mortality rate of 15% are used to define increased mortality in patients with ACLF[4]. In this sense, our findings suggest that patients without extrahepatic organ failures could be defined as ACLF as well, when they present with acutely deteriorated liver function, defined by jaundice and coagulopathy. It is likely that presence of “extrahepatic organ failures”may reflect severity of ACLF, however, it may not be a prerequisite for being defined as ACLF. In fact, the APASL definition does not require “extrahepatic organ failures” to define ACLF[3].

This study had some limitations. First, some of information on precipitating events could not be obtained regardless of thorough review of medical records because of the retrospective study design. We defined acute deteriorated liver function by jaundice and coagulopathy, as suggested by APASL[15]. However, in the CANONIC study, acute development of large ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, bacterial infection or any combination of above, are used to define acute deteriorated liver function[4]. Thus, patients who do not fulfill APASL criteria for liver failure, but present with acute deteriorated liver function, defined in the CANONIC study, are beyond the scope of this study. Lastly, sample size was relatively small, requiring larger scale, prospective study.

In conclusion, ACLF is a distinct syndrome that can be defined as acute deteriorated liver function, precipitated by either direct or indirect injury to the liver, resulting in high short-term mortality with LT as a curative option. The study showed that all spectrum of chronic liver patients with acute deteriorated liver function defined by jaundice (serum bilirubin ≥ 5 mg/dL) and coagulopathy (PT INR ≥ 1.5) can be defined as ACLF. The newly proposed ACLF classification was clinically relevant because different insults and response could be expected, which also suggest different pathophysiology, different management strategy, and different long-term outcome. This suggest that classifying ACLF subtype according to the severity of underlying liver disease is useful for defining, clarifying and comparing ACLF.

There has been a great heterogeneity in defining the acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). Recently, ACLF subtype according to the severity of underlying liver disease has been proposed.

Retrospective cohort of chronic liver disease patients with acute deteriorated liver function were analyzed to see whether ACLF subtype is useful.

The study showed that all spectrum of chronic liver patients with acute deteriorated liver function defined by jaundice (serum bilirubin ≥ 5 mg/dL) and coagulopathy (PT INR ≥ 1.5) can be defined as ACLF. The newly proposed ACLF classification was clinically relevant because different insults and response could be expected, which suggest different pathophysiology, different management strategy, and different long-term outcome.

Classifying ACLF patients into ACLF subtype will better clarify this condition, and can be used in clinical practice.

ACLF is a spectrum of disease with varying severity, characterized by multiple organ failure and high mortality.

This is an interesting and well-written paper addressing an important topic, i.e. the outcome of patients with acute-on-chronic liver disease based on cause of liver disease and precipitating factors of acute disease.

P- Reviewer: Higuera-de la Tijera MF, Tziomalos K S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Jalan R, Gines P, Olson JC, Mookerjee RP, Moreau R, Garcia-Tsao G, Arroyo V, Kamath PS. Acute-on chronic liver failure. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1336-1348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 447] [Cited by in RCA: 456] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Wlodzimirow KA, Eslami S, Abu-Hanna A, Nieuwoudt M, Chamuleau RA. A systematic review on prognostic indicators of acute on chronic liver failure and their predictive value for mortality. Liver Int. 2013;33:40-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sarin SK, Kedarisetty CK, Abbas Z, Amarapurkar D, Bihari C, Chan AC, Chawla YK, Dokmeci AK, Garg H, Ghazinyan H. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) 2014. Hepatol Int. 2014;8:453-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 541] [Cited by in RCA: 497] [Article Influence: 45.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, Pavesi M, Angeli P, Cordoba J, Durand F, Gustot T, Saliba F, Domenicali M, Gerbes A, Wendon J, Alessandria C, Laleman W, Zeuzem S, Trebicka J, Bernardi M, Arroyo V; CANONIC Study Investigators of the EASL-CLIF Consortium. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1426-1437, 1437.e1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1720] [Cited by in RCA: 2165] [Article Influence: 180.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 5. | Katoonizadeh A, Laleman W, Verslype C, Wilmer A, Maleux G, Roskams T, Nevens F. Early features of acute-on-chronic alcoholic liver failure: a prospective cohort study. Gut. 2010;59:1561-1569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Garg H, Kumar A, Garg V, Sharma P, Sharma BC, Sarin SK. Clinical profile and predictors of mortality in patients of acute-on-chronic liver failure. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:166-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Duseja A, Chawla YK, Dhiman RK, Kumar A, Choudhary N, Taneja S. Non-hepatic insults are common acute precipitants in patients with acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF). Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3188-3192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pan HC, Jenq CC, Tsai MH, Fan PC, Chang CH, Chang MY, Tian YC, Hung CC, Fang JT, Yang CW. Scoring systems for 6-month mortality in critically ill cirrhotic patients: a prospective analysis of chronic liver failure - sequential organ failure assessment score (CLIF-SOFA). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1056-1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, Wei WI, Yong BH, Lai CL, Wong J. Live-donor liver transplantation for acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure. Transplantation. 2003;76:1174-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chan AC, Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Chan SC, Ng KK, Yong BH, Chiu A, Lam BK. Liver transplantation for acute-on-chronic liver failure. Hepatol Int. 2009;3:571-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Finkenstedt A, Nachbaur K, Zoller H, Joannidis M, Pratschke J, Graziadei IW, Vogel W. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: excellent outcomes after liver transplantation but high mortality on the wait list. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:879-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jalan R, Yurdaydin C, Bajaj JS, Acharya SK, Arroyo V, Lin HC, Gines P, Kim WR, Kamath PS. Toward an improved definition of acute-on-chronic liver failure. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:4-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yang JD, Kim WR, Coelho R, Mettler TA, Benson JT, Sanderson SO, Therneau TM, Kim B, Roberts LR. Cirrhosis is present in most patients with hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:64-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Muckart DJ, Bhagwanjee S. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference definitions of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and allied disorders in relation to critically injured patients. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1789-1795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sarin SK, Kumar A, Almeida JA, Chawla YK, Fan ST, Garg H, de Silva HJ, Hamid SS, Jalan R, Komolmit P. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the study of the liver (APASL). Hepatol Int. 2009;3:269-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 630] [Cited by in RCA: 643] [Article Influence: 40.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | El-Serag HB, Everhart JE. Diabetes increases the risk of acute hepatic failure. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1822-1828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jha AK, Nijhawan S, Rai RR, Nepalia S, Jain P, Suchismita A. Etiology, clinical profile, and inhospital mortality of acute-on-chronic liver failure: a prospective study. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2013;32:108-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Karvellas CJ, Pink F, McPhail M, Austin M, Auzinger G, Bernal W, Sizer E, Kutsogiannis DJ, Eltringham I, Wendon JA. Bacteremia, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II and modified end stage liver disease are independent predictors of mortality in critically ill nontransplanted patients with acute on chronic liver failure. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:121-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Solà E, Ginès P. Renal and circulatory dysfunction in cirrhosis: current management and future perspectives. J Hepatol. 2010;53:1135-1145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bajaj JS, O’Leary JG, Reddy KR, Wong F, Biggins SW, Patton H, Fallon MB, Garcia-Tsao G, Maliakkal B, Malik R. Survival in infection-related acute-on-chronic liver failure is defined by extrahepatic organ failures. Hepatology. 2014;60:250-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 435] [Article Influence: 39.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Thabut D, Massard J, Gangloff A, Carbonell N, Francoz C, Nguyen-Khac E, Duhamel C, Lebrec D, Poynard T, Moreau R. Model for end-stage liver disease score and systemic inflammatory response are major prognostic factors in patients with cirrhosis and acute functional renal failure. Hepatology. 2007;46:1872-1882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Thadhani R, Pascual M, Bonventre JV. Acute renal failure. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1448-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1291] [Cited by in RCA: 1162] [Article Influence: 40.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Terra C, Guevara M, Torre A, Gilabert R, Fernández J, Martín-Llahí M, Baccaro ME, Navasa M, Bru C, Arroyo V. Renal failure in patients with cirrhosis and sepsis unrelated to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: value of MELD score. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1944-1953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ginès P, Fernández J, Durand F, Saliba F. Management of critically-ill cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol. 2012;56 Suppl 1:S13-S24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cordoba J, Ventura-Cots M, Simón-Talero M, Amorós À, Pavesi M, Vilstrup H, Angeli P, Domenicali M, Ginés P, Bernardi M. Characteristics, risk factors, and mortality of cirrhotic patients hospitalized for hepatic encephalopathy with and without acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). J Hepatol. 2014;60:275-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yan H, Wu W, Yang Y, Wu Y, Yang Q, Shi Y. A novel integrated Model for End-Stage Liver Disease model predicts short-term prognosis of hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure patients. Hepatol Res. 2015;45:405-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |