Published online Mar 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2793

Peer-review started: September 1, 2014

First decision: September 29, 2014

Revised: November 21, 2014

Accepted: December 19, 2014

Article in press: December 22, 2014

Published online: March 7, 2015

Processing time: 192 Days and 1.3 Hours

AIM: To compare the tolerability of magnifying narrow band imaging endoscopy for esophageal cancer screening with that of lugol chromoendoscopy.

METHODS: We prospectively enrolled and analyzed 51 patients who were at high risk for esophageal cancer. All patients were divided into two groups: a magnifying narrow band imaging group, and a lugol chromoendoscopy group, for comparison of adverse symptoms. Esophageal cancer screening was performed on withdrawal of the endoscope. The primary endpoint was a score on a visual analogue scale for heartburn after the examination. The secondary endpoints were scale scores for retrosternal pain and dyspnea after the examinations, change in vital signs, total procedure time, and esophageal observation time.

RESULTS: The scores for heartburn and retrosternal pain in the magnifying narrow band imaging group were significantly better than those in the lugol chromoendoscopy group (P = 0.004, 0.024, respectively, ANOVA for repeated measures). The increase in heart rate after the procedure was significantly greater in the lugol chromoendoscopy group. There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to other vital sign. The total procedure time and esophageal observation time in the magnifying narrow band imaging group were significantly shorter than those in the lugol chromoendoscopy group (450 ± 116 vs 565 ± 174, P = 0.004, 44 ± 26 vs 151 ± 72, P < 0.001, respectively).

CONCLUSION: Magnifying narrow band imaging endoscopy reduced the adverse symptoms compared with lugol chromoendoscopy. Narrow band imaging endoscopy is useful and suitable for esophageal cancer screening periodically.

Core tip: We conducted prospective randomized study to determine whether magnifying narrow band imaging (NBI) endoscopy would reduce the adverse symptoms compared with lugol chromoendoscopy. Total, 51 patients who were at high risk for esophageal cancer were enrolled. All patients were divided into two groups for comparison of adverse symptoms. The visual analogue scale scores for heartburn and retrosternal pain in the magnifying NBI group were significantly better than those in the lugol chromoendoscopy group. Magnifying NBI endoscopy reduced the adverse symptoms compared with lugol chromoendoscopy. NBI endoscopy is very useful and suitable for screening esophageal cancer patients periodically.

- Citation: Yamasaki Y, Takenaka R, Hori K, Takemoto K, Kawano S, Kawahara Y, Okada H, Fujiki S, Yamamoto K. Tolerability of magnifying narrow band imaging endoscopy for esophageal cancer screening. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(9): 2793-2799

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i9/2793.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2793

Esophageal cancer is the sixth most common cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide[1]. The overall 5-year survival rate in patients with esophageal cancer is about 15%[2]. However, superficial esophageal cancer is becoming treatable and curable due to recent technical improvements in endoscopy[3,4]. Thus, it is important to detect esophageal cancer at an early stage. It was reported that the health risk appraisal-flushing (HRA-F) score was useful to identify patients who were at high risk for esophageal cancer[5]. In addition, it was reported that patients who had primary head and neck cancer had a high incidence of esophageal cancer[6]. Therefore, periodic screening of these patients by endoscopy would be expected to provide great benefits[7].

Detection of superficial esophageal cancer is difficult by conventional endoscopic white light imaging alone. Lugol chromoendoscopy has been used to detect superficial esophageal cancer. However, staining of the esophagus with lugol often causes mucosal irritation leading to retrosternal pain and discomfort[8-10]. These adverse symptoms may prevent patients from undergoing endoscopy periodically. Current reports suggest that the sensitivity and specificity of narrow band imaging (NBI) endoscopy for detecting superficial esophageal cancer were comparable to those of lugol chromoendoscopy[11-13]. NBI endoscopy is recently being used more frequently in esophageal screening. Moreover, NBI might not cause adverse symptoms after endoscopy. In order to detect superficial esophageal cancer, it is important to offer high-risk patients the esophageal screening endoscopy periodically[7]. Thus, comfortable and easy esophageal screening endoscopy is required, but the tolerability of esophageal screening endoscopy has rarely been studied.

The aim of this study was to compare the tolerability of the magnifying NBI endoscopy for esophageal screening in patients at high risk for esophageal cancer with that of lugol chromoendoscopy.

This study was designed as a randomized controlled trial and was conducted in Tsuyama Chuo Hospital, Japan. The study protocol was approved by the ethics Committee of the Tsuyama Chuo Hospital, and was registered in the University Hospital Medical Network Clinical Trials Registry as number UMIN 000012097.

The inclusion criteria included more than six points in HRA-F score for esophageal cancer[5,7] or a past history of head and neck squamous cell cancer. Patients were excluded if they had a history of iodine hypersensitivity or severe organ failure. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment.

Randomization of the participants was carried out using sealed envelopes. Before endoscopy, participants were randomly assigned to the magnifying NBI endoscopy group (NBI group) or the lugol chromoendoscopy group (Lugol group).

All procedures were carried out using magnifying endoscopes (GIF-H260Z, Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) and a standard video endoscope system (EVIS LUCERA, Olympus Optical) by two endoscopists (Y.Y and R.T, with more than 5 years’ experience of conventional endoscopy). They had experienced more than 2000 esophagogastroduodenoscopies, and had more than 4 year of experience with NBI. R.T had specialist qualifications from the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society. These cases were divided almost equally between the two endoscopists. All procedures were carried out without sedation. The endoscopic screening examination was performed on withdrawal of the endoscope by using either magnifying NBI endoscopy or lugol chromoendoscopy. All parts of the esophagus, which included the distance from the cervical esophagus to the esophagogastric junction, were evaluated.

Blood pressure, heart rate and peripheral arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) were measured before and after the procedure. The esophageal observation time required for the cancer screening on withdrawal of the endoscope and the total procedure time were measured. The presence of gag reflex during esophageal observation was monitored by a medical staff uninvolved with the procedure.

In the NBI group, a magnifying examination was conducted to evaluate the intra-epithelial papillary capillary loops (IPCL) pattern and background coloration when abnormal mucosal areas were identified by non-magnifying NBI endoscopy. If dilated and tortuous IPCL patterns and brownish color changes in the areas between IPCL were observed[14,15], we defined the area as an abnormal lesion. In the Lugol group, a 1.2% lugol solution was sprayed over the entire esophageal mucosa. A well demarcated, unstained area was defined as a lugol-voiding lesion (LVL). After examination, a 2.5 % sodium thiosulfate hydrate solution was sprayed over the esophageal mucosa to bleach the lugol.

Biopsy specimens were obtained using disposable forceps from well demarcated brownish areas with abnormal IPCL and brownish color change, or from LVL greater than 5mm in diameter. All specimens were evaluated by a single experienced pathologist, who was blinded to the clinical backgrounds of the patients. Histological observations were classified into four categories according to the World Health Organization classification[16]: Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (HGIN), low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (LGIN), and negative for neoplasia (no atypia).

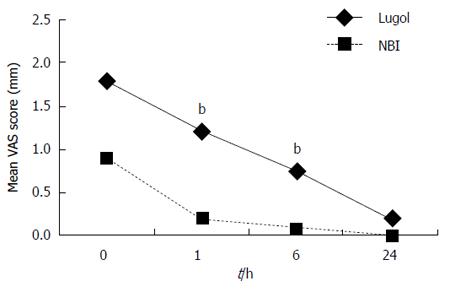

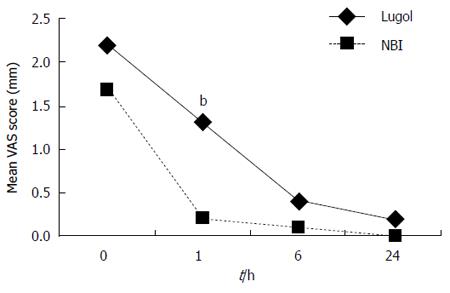

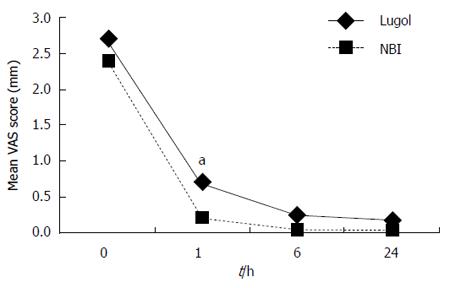

A 100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS) consisting of a horizontal line 100 mm in length was used for measuring patient heartburn, retrosternal pain and dyspnea (0 mm = painless, 100 mm = extremely painful)[17]. Patients recorded the level of the experienced symptoms at four time points: immediately, 1 h, 6 h and 24 h after the examination. The VAS scores were the distance measured to the nearest millimeter from the left end of the line to the point of the patient’s mark. A questionnaire was given to the patients to take home to complete as instructed at intervals of 1, 6 and 24 h, and the completed forms were then mailed to the hospital the following day. The completed questionnaires were subsequently mailed to our medical office.

The primary outcome variable was VAS score for heartburn after the examination. The secondary outcome variables were VAS scores for retrosternal pain and dyspnea after the examinations, change in vital signs after the examination, presence of gag reflex during esophageal observation, total procedure time, and esophageal observation time.

A preliminary pilot study was conducted to estimate the standard deviation (SD) of the VAS score for heartburn after the examination. With an assumed SD of 15 mm, the study sample size was calculated at 48 patients in order to have an 80% power with two-sided α levels of 0.05 to detect any differences in VAS scores between the two groups. The final sample required was 52 patients in order to accommodate an attrition rate of 10%.

Results are presented as mean values ± SD. The χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare categorical data, and the Wilcoxon’s rank sum test was used to compare continuous data. ANOVA was used for repeated measures statistical analysis of VAS scores for heartburn, retrosternal pain and dyspnea. Wilcoxon’s rank sum test was used to compare VAS scores at each measurement point.

The JMP (version 8) software package (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States) and Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, United States) were used for statistical analyses, and a P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Yasushi Yamasaki from Tsuyama Chuo Hospital.

Between March 2012 and December 2013, 52 consecutive patients were enrolled in this study at Tsuyama Chuo Hospital. They were randomized into two groups prior to their endoscopy procedure. Among those, 1 patient was excluded because a completed questionnaire was not received. Thus, 51 patients were analyzed. Twenty-five patients were assigned to the NBI group and 26 patients to the Lugol group. There were no differences in clinical characteristics between the two study groups (Table 1).

| Clinical parameters | NBI (n = 25) | Lugol (n = 26) | P value |

| Age, yr | 60 ± 11 | 61 ± 8 | 0.597 |

| Male/female, n | 25/0 | 25/1 | 1.000 |

| HRA-F score | 8 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 0.277 |

| Past history of head and neck cancer, n | 0 | 1 | 1.000 |

| Previous EGD, times | 4 ± 3 | 3 ± 2 | 0.475 |

The mean VAS scores for heartburn, retrosternal pain and dyspnea after the examinations are shown in Figures 1, 2 and 3. The VAS scores for heartburn and retrosternal pain in the NBI group were significantly better than those in the Lugol group (P = 0.004, 0.024, respectively, ANOVA for repeated measures). There were no differences in the VAS scores for dyspnea between the two groups (ANOVA for repeated measures).

Comparison by Wilcoxon’s rank sum test at each measurement point showed that the VAS scores for heartburn at 1h and 6h after the examinations were better in the NBI group than those in the Lugol group (P < 0.01). Similarly, the VAS scores for retrosternal pain and dyspnea at 1h after the examination were better in the NBI group than those in the Lugol group (P < 0.01, P < 0.05, respectively).

The results of other endpoints are shown in Table 2. The increase in heart rate after the procedure was significantly greater in the Lugol group. There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to increase in blood pressure, decrease in SpO2 and the presence of gag reflex. The total procedure time in the NBI group was significantly shorter than that in the Lugol group (P = 0.004), and the esophageal observation time in the NBI group was also significantly shorter than that in the Lugol group (P < 0.001).

| Variables | NBI (n = 25) | Lugol (n = 26) | P value |

| Increase in SBP after procedure (> 20 mmHg), n | 6 | 8 | 0.755 |

| Increase in DBP after procedure (> 20 mmHg), n | 1 | 5 | 0.190 |

| Increase in HR after procedure (> 20 bpm), n | 7 | 16 | 0.024 |

| Decrease in SpO2 (> 3 %), n | 1 | 3 | 0.609 |

| Gag reflex, n | 1 | 6 | 0.099 |

| Total procedure time, second | 450 ± 116 | 565 ± 174 | 0.004 |

| Esophageal observation time, second | 44 ± 26 | 151 ± 72 | < 0.001 |

There was no significant difference between the two endoscopists with respect to the mean VAS scores for heartburn, retrosternal pain and dyspnea after the examinations, procedure time and change of vital signs in each group.

The results of biopsies are shown in Table 3. Seven lesions in 7 patients underwent endoscopic biopsy. One lesion was detected by NBI, and 6 lesions were detected by lugol staining. Of these, only one lesion in the Lugol group was histologically confirmed to be HGIN or SCC. There were no differences in biopsy specimens from esophageal lesions between the two groups.

| Variables | NBI (n = 25) | Lugol (n = 26) | P value |

| Biopsy from esophageal lesion, n | 1 | 6 | 0.099 |

| Biopsy result, n | |||

| No atypia or LGIN | 1 | 5 | |

| HGIN or SCC | 0 | 1 |

In this prospective study, we demonstrated that magnifying NBI endoscopy reduced adverse symptoms in esophageal cancer screening compared with lugol chromoendoscopy. In the NBI group, the VAS scores for heartburn and retrosternal pain after endoscopy were significantly better than those in the Lugol group.

Several reports have indicated that staining by lugol can damage the mucosa of the esophagus and stomach, leading to adverse symptoms such as heartburn and retrosternal pain[8-10]. In addition, it can even induce erosion or ulceration in the esophagus and stomach due to hypersensitivity to lugol[18-20]. Although sodium thiosulfate solution was reported to decrease adverse symptoms induced by lugol solution in the esophagus and stomach, these symptoms were not completely eliminated[9,10]. In fact, more than half of the patients who received sprayed sodium thiosulfate solution after lugol chromoendoscopy reported some acute adverse symptoms, and 13% of the patients reported late adverse symptoms, which occurred more than 30 min after endoscopy[10].

By contrast, NBI endoscopy is easily activated by pushing a button on the endoscope without using any solution[21,22]. Thus, NBI endoscopy has been considered to be more suitable than lugol chromoendoscopy. However, no comparative study had been carried out to confirm the adverse symptoms after NBI endoscopy or lugol chromoendoscopy. Therefore, we conducted a randomized prospective study to compare the adverse symptoms of the two different endoscopy procedures for the screening of esophageal cancer. In this study, we concluded that magnifying NBI endoscopy was more suitable than lugol chromoendoscopy. In addition, the procedure time in the NBI group was significantly shorter, and the increase in heart rate was significantly less than the corresponding values in the Lugol group. To remove an effect of biopsy, we evaluated the adverse symptoms and esophageal observation time in 44 patients without biopsy. Twenty-four patients in the NBI group and 20 patients in the Lugol group were compared. The mean esophageal observation time in the NBI group was 39 ± 14 s, and that in the Lugol group was 122 ± 34 s (P < 0.001). In the same way, the VAS scores for heartburn in the NBI group were significantly better than those in the Lugol group (P = 0.021, ANOVA for repeated measures). There were no differences in the VAS scores for retrosternal pain between the two groups (P = 0.074, ANOVA for repeated measures). These results enhanced the reliability of our conclusion (data not shown).

The accuracy of NBI endoscopy in screening for esophageal cancer has been reported to be comparable to that of lugol chromoendoscopy. Especially, the specificity of NBI endoscopy with or without magnifying imaging was higher than that of lugol chromoendoscopy[11,12]. Although lugol chromoendoscopy is the current gold standard for screening for esophageal cancer, NBI endoscopy might be the first-choice endoscopy for screening in the future. NBI endoscopy is useful for screening because this modality is less likely to cause adverse symptoms and requires a short time to observe the esophagus. It was reported that NBI is easily applied with a modicum of experience[22]. A little training makes it possible to detect brownish areas in magnifying NBI. In this study, NBI endoscopy was performed with a mean time of 39 s enough to observe the entire esophagus if there was no well demarcated brownish area.

Nevertheless, NBI endoscopy alone is not sufficient for checking high risk patients for esophageal cancer throughout life. A few SCC, which were flat, 5-10mm in diameter, multiple synchronous and located in the upper esophagus, were missed by NBI endoscopy in past studies[11,12,23]. These lesions were detected by lugol chromoendoscopy. In addition, the severity of LVLs, especially when present in large numbers and large sizes, were reported to be precursors for esophageal cancers[6,24,25], but NBI endoscopy has been unable to predict the risk for esophageal cancer. Thus, for the initial endoscopy for esophageal screening of patients at high risk for esophageal cancer, lugol chromoendoscopy is recommended as best suited to predict the risk for esophageal cancer and to determine the intervals for surveillance and screening endoscopy. Then, from the second endoscopy on, we recommend that NBI endoscopy should be periodically performed as a painless screening procedure.

Even though we successfully revealed the tolerability of the magnifying NBI endoscopy for esophageal cancer screening, there are several limitations to this study. First, this study is a single-center analysis performed by only two endoscopists. A multicenter trial may be required to generalize these results globally. Second, the concentration of lugol solutions could possibly affect the adverse symptoms. Although a lower concentration of lugol solution, especially less than 1%, might reduce the symptoms, it might make LVLs unclear.

In conclusion, we have conducted the first randomized controlled study to compare the tolerability of the magnifying NBI endoscopy with that of lugol chromoendoscopy in esophageal cancer screening. The NBI endoscopy reduced the adverse symptoms, total procedure time and esophageal observation time compared with lugol chromoendoscopy.

Detection of superficial esophageal cancer is difficult by conventional endoscopic white light imaging alone. Lugol chromoendoscopy has been used to detect superficial esophageal cancer as gold standard. However, staining of the esophagus with lugol often causes adverse symptoms. These adverse symptoms may prevent patients from undergoing endoscopy periodically. Current reports suggest that the sensitivity and specificity of narrow band imaging (NBI) endoscopy for detecting superficial esophageal cancer were comparable to those of lugol chromoendoscopy. NBI might not cause adverse symptoms after endoscopy. However, no study has compared the tolerability of NBI endoscopy and lugol chromoendoscopy.

The current research hotspot is whether NBI reduce adverse symptoms after endoscopy or not.

Previous reports indicated that lugol chromoendoscopy can damage the mucosa of the esophagus and stomach, leading to adverse symptoms. However, symptom after NBI endoscopy is unclear. In this study, NBI endoscopy reduced adverse symptoms in esophageal cancer screening compared with lugol chromoendoscopy. In addition, the procedure time by NBI endoscopy was significantly shorter than that by lugol chromoendoscopy.

The study results indicate that the authors can perform esophageal cancer screening by NBI endoscopy painlessly. In future, NBI endoscopy might be the first-choice endoscopy for esophageal cancer screening.

NBI is an innovative optical technology that can clearly visualize the microvascular structure of the organ surface. Especially NBI detected squamous cell carcinoma as well demarcated brownish area.

This study aimed to compare the tolerability of magnifying NBI and lugol chromoendoscopy in the screening of esophageal cancer. The authors found the magnifying NBI had less adverse symptoms, less affecting HR and shorter procedure time. These results suggest that NBI endoscopy should be periodically performed as a painless screening procedure.

P- Reviewer: Lorenzo-Zuniga V, Tseng PH S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in RCA: 25543] [Article Influence: 1824.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 2. | Polednak AP. Trends in survival for both histologic types of esophageal cancer in US surveillance, epidemiology and end results areas. Int J Cancer. 2003;105:98-100. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Higuchi K, Tanabe S, Azuma M, Katada C, Sasaki T, Ishido K, Naruke A, Katada N, Koizumi W. A phase II study of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal neoplasms (KDOG 0901). Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:704-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yamashina T, Ishihara R, Nagai K, Matsuura N, Matsui F, Ito T, Fujii M, Yamamoto S, Hanaoka N, Takeuchi Y. Long-term outcome and metastatic risk after endoscopic resection of superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:544-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yokoyama T, Yokoyama A, Kumagai Y, Omori T, Kato H, Igaki H, Tsujinaka T, Muto M, Yokoyama M, Watanabe H. Health risk appraisal models for mass screening of esophageal cancer in Japanese men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2846-2854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Muto M, Takahashi M, Ohtsu A, Ebihara S, Yoshida S, Esumi H. Risk of multiple squamous cell carcinomas both in the esophagus and the head and neck region. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1008-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Yokoyama A, Kumagai Y, Yokoyama T, Omori T, Kato H, Igaki H, Tsujinaka T, Muto M, Yokoyama M, Watanabe H. Health risk appraisal models for mass screening for esophageal and pharyngeal cancer: an endoscopic follow-up study of cancer-free Japanese men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:651-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fagundes RB, de Barros SG, Pütten AC, Mello ES, Wagner M, Bassi LA, Bombassaro MA, Gobbi D, Souto EB. Occult dysplasia is disclosed by Lugol chromoendoscopy in alcoholics at high risk for squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Endoscopy. 1999;31:281-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kameyama H, Murakami M, Shimizu Y, Fukoe Y, Ree U, Ree M, Ando S, Tanio N, Arai K, Kusano M. The efficacy and diagnostic significance of sodium thiosulphate solution spraying after iodine dyeing of the esophagus. Dig Endosc. 1994;6:181-186. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kondo H, Fukuda H, Ono H, Gotoda T, Saito D, Takahiro K, Shirao K, Yamaguchi H, Yoshida S. Sodium thiosulfate solution spray for relief of irritation caused by Lugol’s stain in chromoendoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:199-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Takenaka R, Kawahara Y, Okada H, Hori K, Inoue M, Kawano S, Tanioka D, Tsuzuki T, Uemura M, Ohara N. Narrow-band imaging provides reliable screening for esophageal malignancy in patients with head and neck cancers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2942-2948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nagami Y, Tominaga K, Machida H, Nakatani M, Kameda N, Sugimori S, Okazaki H, Tanigawa T, Yamagami H, Kubo N. Usefulness of non-magnifying narrow-band imaging in screening of early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective comparative study using propensity score matching. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:845-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kuraoka K, Hoshino E, Tsuchida T, Fujisaki J, Takahashi H, Fujita R. Early esophageal cancer can be detected by screening endoscopy assisted with narrow-band imaging (NBI). Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:63-66. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Yoshida T, Inoue H, Usui S, Satodate H, Fukami N, Kudo SE. Narrow-band imaging system with magnifying endoscopy for superficial esophageal lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:288-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kanzaki H, Ishihara R, Ishiguro S, Nagai K, Matsui F, Yamashina T, Ohta T, Yamamoto S, Hanaoka N, Hanafusa M. Histological features responsible for brownish epithelium in squamous neoplasia of the esophagus by narrow band imaging. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:274-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gabbert HE, Shimoda T, Hainaut P, Nakamura Y, Field JK, Inoue H. Squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Pathology and Genetics of the Digestive System: World Health Organization Classification. Lyon: IARC press 2000; 11-19. |

| 17. | Wewers ME, Lowe NK. A critical review of visual analogue scales in the measurement of clinical phenomena. Res Nurs Health. 1990;13:227-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1525] [Cited by in RCA: 1579] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sreedharan A, Rembacken BJ, Rotimi O. Acute toxic gastric mucosal damage induced by Lugol’s iodine spray during chromoendoscopy. Gut. 2005;54:886-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Thuler FP, de Paulo GA, Ferrari AP. Chemical esophagitis after chromoendoscopy with Lugol’s solution for esophageal cancer: case report. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:925-926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Park JM, Seok Lee I, Young Kang J, Nyol Paik C, Kyung Cho Y, Woo Kim S, Choi MG, Chung IS. Acute esophageal and gastric injury: complication of Lugol’s solution. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:135-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Muto M, Katada C, Sano Y, Yoshida S. Narrow band imaging: a new diagnostic approach to visualize angiogenesis in superficial neoplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S16-S20. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Muto M, Minashi K, Yano T, Saito Y, Oda I, Nonaka S, Omori T, Sugiura H, Goda K, Kaise M. Early detection of superficial squamous cell carcinoma in the head and neck region and esophagus by narrow band imaging: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1566-1572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 427] [Cited by in RCA: 526] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lee YC, Wang CP, Chen CC, Chiu HM, Ko JY, Lou PJ, Yang TL, Huang HY, Wu MS, Lin JT. Transnasal endoscopy with narrow-band imaging and Lugol staining to screen patients with head and neck cancer whose condition limits oral intubation with standard endoscope (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:408-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Muto M, Hironaka S, Nakane M, Boku N, Ohtsu A, Yoshida S. Association of multiple Lugol-voiding lesions with synchronous and metachronous esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in patients with head and neck cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:517-521. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Hori K, Okada H, Kawahara Y, Takenaka R, Shimizu S, Ohno Y, Onoda T, Sirakawa Y, Naomoto Y, Yamamoto K. Lugol-voiding lesions are an important risk factor for a second primary squamous cell carcinoma in patients with esosphageal cancer or head and neck cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:858-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |