Published online Feb 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i8.2522

Peer-review started: June 19, 2014

First decision: July 9, 2014

Revised: July 20, 2014

Accepted: August 28, 2014

Article in press: August 28, 2014

Published online: February 28, 2015

Processing time: 254 Days and 18.2 Hours

AIM: To access the efficacy of combination with amoxicillin and tetracycline for eradication of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), thus providing clinical practice guidelines.

METHODS: PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Science Citation Index, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang, and Chinese Biomedical Literature databases and abstract books of major European, American, and Asian gastroenterological meetings were searched. All clinical trials that examined the efficacy of H. pylori eradication therapies and included both tetracycline and amoxicillin in one study arm were selected for this systematic review and meta-analysis. Statistical analysis was performed with Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software (Version 2). Subgroup, meta-regression, and sensitivity analyses were also carried out.

RESULTS: Thirty-three studies met the inclusion criteria. The pooled odds ratio (OR) was 0.90 (95%CI: 0.42-1.78) for quadruple therapy with amoxicillin and tetracycline vs other quadruple regimens, and total eradication rates were 78.1% by intention-to-treat (ITT) and 84.5% by per-protocol (PP) analyses in the experimental groups. The pooled eradication rates of 14-d quadruple regimens with a combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline were 82.3% by ITT and 89.0% by PP, and those of 10-d regimens were 84.6% by ITT and 93.7% by PP. The OR by ITT were 1.21 (95%CI: 0.64-2.28) for triple regimens with amoxicillin and tetracycline vs other regimens and 1.81 (95%CI: 1.37-2.41) for sequential treatment with amoxicillin and tetracycline vs other regimens, respectively.

CONCLUSION: The effectiveness of regimens employing amoxicillin and tetracycline for H. pylori eradication may be not inferior to other regimens, but further study should be necessary.

Core tip: The combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline is an attractive alternative because of its low cost, low resistance rate, and safety. We conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials to compare the efficacy of the combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline with other therapies for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. Available data suggest that 10- or 14-d quadruple regimens with amoxicillin and tetracycline can achieve acceptable eradication rates and may be suitable for the treatment of H. pylori infection.

-

Citation: Lv ZF, Wang FC, Zheng HL, Wang B, Xie Y, Zhou XJ, Lv NH. Meta-analysis: Is combination of tetracycline and amoxicillin suitable for

Helicobacter pylori infection? World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(8): 2522-2533 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i8/2522.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i8.2522

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection affects approximately 50%-75% of the population worldwide[1] and contributes to several gastrointestinal diseases, including peptic ulcer, gastric cancer, and gastric mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma[2,3]. Standard triple regimens, consisting of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) plus two of the three antibiotics amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and metronidazole, have been recommended as first-line anti-H. pylori therapy for the past decade by several countries and regions[4,5]. However, with those regimens used widely, the prevalence of H. pylori resistance to metronidazole and clarithromycin is increasing[6-9], which results in the failure to eradicate H. pylori[10], and eradication rates of H. pylori have declined to unacceptable levels[11-14].

A regimen with PPI, bismuth, tetracycline, and metronidazole has been recommended for first-line or second-line therapy for H. pylori infection in several recent consensuses[15,16]. The increasing resistance rate of H. pylori to metronidazole may affect the efficacy of this regimen for H. pylori infection[17]. Many studies have shown that H. pylori resistance to amoxicillin and tetracycline is rare[7,18], and therefore combination treatment with amoxicillin and tetracycline has provoked some investigators’ attention as an anti-H. pylori therapy. In theory, regimens combining amoxicillin and tetracycline should provide an excellent eradication rate for H. pylori infection. Nevertheless, some controversies exist regarding the ability of combined amoxicillin and tetracycline to eradicate H. pylori. Amoxicillin is a bactericidal drug that interferes with cell wall synthesis, and it can exert excellent antibacterial activity during the bacterial breeding period. Tetracycline can rapidly inhibit bacterial growth by inhibiting cellular protein synthesis. Therefore, the combination of these two agents may appear antagonistic despite H. pylori having high susceptibility to both amoxicillin and tetracycline in vitro. But the similar combination of clarithromycin and amoxicillin has commonly been used for H. pylori infection for decades. Is a regimen containing tetracycline and amoxicillin suitable for H. pylori infection?

Trials on the combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline for H. pylori infection have been performed; however, their results are conflicting. Some studies have suggested that this combination did not improve eradication rates, and even obtained poor eradication effects during anti-H. pylori treatment[19-22]. In contrast, other studies have suggested that this combination positively affected eradication rates as a second- or third-line choice for H. pylori infection[23-26]. Our preliminary data also indicated that regimens comprising PPI, bismuth, amoxicillin, and tetracycline could achieve an acceptable eradication rate [85.7% by intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis; data unpublished].

What is the real efficacy of the combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline during anti-H. pylori treatment? We conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to compare the efficacy of the combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline with other therapies for H. pylori infection to supply some useful information for clinical practice.

We developed this meta-analysis according to PRISMA statement guideline[27]. We searched the databases of PubMed (to April 2014), EMBASE (1946 to April 2014), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Issue 4, 2014), and the Science Citation Index (SCI) (1945 to April 2014) according to Medical Subject Heading and text terms: (H. pylori) and amoxicillin and tetracycline. We also searched the literature using the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang, and Chinese Biomedical Literature databases (CBM) according to the same Subject Heading and text terms. We imposed no language restrictions. We also searched the abstracts of major gastroenterological meetings, such as the Digestive Disease Week of the American Gastroenterological Association (DDW) (2008-2013) and European Helicobacter Study Group (2008-2013). Furthermore, we asked authors to provide unpublished RCT results. In addition, we searched the ClinicalTrials.gov website for registered RCTs with unpublished data and identified relevant studies from the reference list of each selected article.

Studies deemed eligible for inclusion in the systemic review and meta-analysis met the following inclusion criteria: (1) clinical trials; (2) any age, endoscopic findings, and symptoms at the time of enrollment; (3) confirmation of eradication outcome by urea breath test, histology, or H. pylori stool antigen at least 4 wk after therapy; and (4) eradication regimens of the experimental group, including both tetracycline and amoxicillin.

Studies were excluded under the following circumstances: (1) eradication date could not be determined; (2) articles and abstracts in a language other than English or Chinese, unless they were translated; and (3) amoxicillin and tetracycline not included in the same experimental group.

Two authors (Lv ZF and Wang FC) extracted the relevant data and entered them into standardized data abstraction sheets. These data contained the study quality and type, anti-H. pylori regimens, duration of treatment, location of trials, time of publication, number and age of enrolled patients, diagnostic methods for detecting H. pylori infection before enrolment and after study completion, eradication rates by ITT, rates of successful and failed eradication, and total adverse effects (diarrhea, vomiting or nausea, epigastric pain, headache, total adverse effects) from all included studies.

Two reviewers (Lv ZF and Wang FC) independently assessed the quality of the studies that met the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by consulting a third reviewer (YX). The quality of data reporting was applied using a 3-item, 5-point Jadad scale. The scores were evaluated according to three criteria: randomization (score 0-2), double blinding (score 0-2), and description of withdrawals and dropouts (score 0-1) as previously described[28,29]. To avoid duplication of data, if trials were published repeatedly by the same authors or institutions, only the most recently published article was included.

The primary outcome for the systemic analysis was the efficacy of regimens with amoxicillin and tetracycline compared with other regimens for eradicating H. pylori infection. The secondary outcome was safety of the combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline. We measured H. pylori eradication efficacy using odds ratio (OR) with 95%CI. When data could be combined, meta-analyses were performed. If not, we described the results based on ITT and adverse events. Heterogeneity tests were performed using the Q-test, and a 10% cut-off for statistical significance was employed. The heterogeneity index (I2) was calculated, and the OR for all studies were pooled into a summary OR using a fixed-effects model or a random effects model, based on inverse variance methods. The fixed-effects model was used when heterogeneity was not statistically significant; otherwise, the random effects model was employed. If the data were found to be heterogeneous, we searched for sources of heterogeneity by meta-regression and subgroup analyses. A Z-test was also used to assess the pooled effects. We employed funnel plot, Egger’s test, and Begg’s test to estimate publication bias, with a two-sided P value of 0.10 or less considered significant. We used Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software (version 2) to perform the statistical analysis.

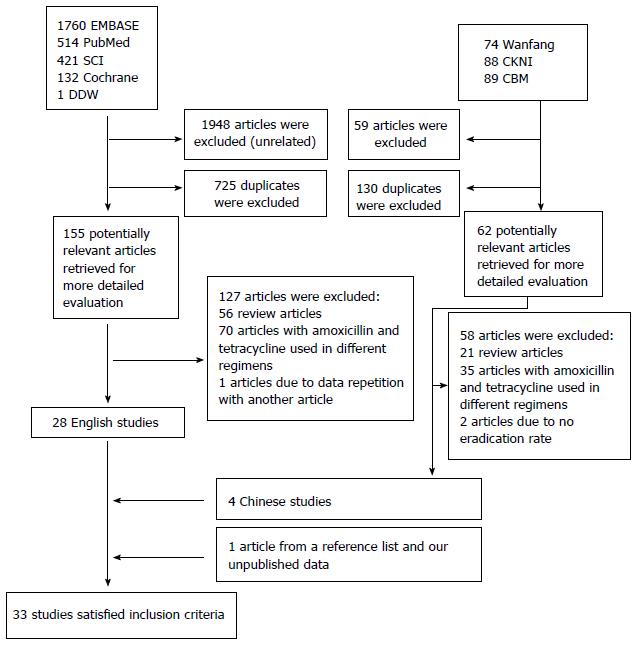

A flow diagram of this systematic review is shown in Figure 1. The bibliographical search yielded a total of 3078 articles, of which 2827 were from PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Embase, and SCI, while another 251 articles, published in Chinese, were from CNKI, Wanfang, and CBM databases, and one abstract was from DDW (2008-2013). We first excluded 2007 articles due to uncorrelated with our study, and 855 due to duplicates. We retrieved 217 articles for detailed evaluation, among which 105 studies were excluded because amoxicillin and tetracycline were not used in the same experimental group. We also excluded 77 review articles, 2 articles in which eradication data could not be obtained[30,31], and 1 other article (one abstract) that were published repeatedly[32]. One article identified from a reference list was also included in the meta-analysis. Ultimately, 33 studies (2 abstracts, 30 full-text articles and our unpublished data), were included in the systemic review and meta-analysis[17,19-26,33-55].

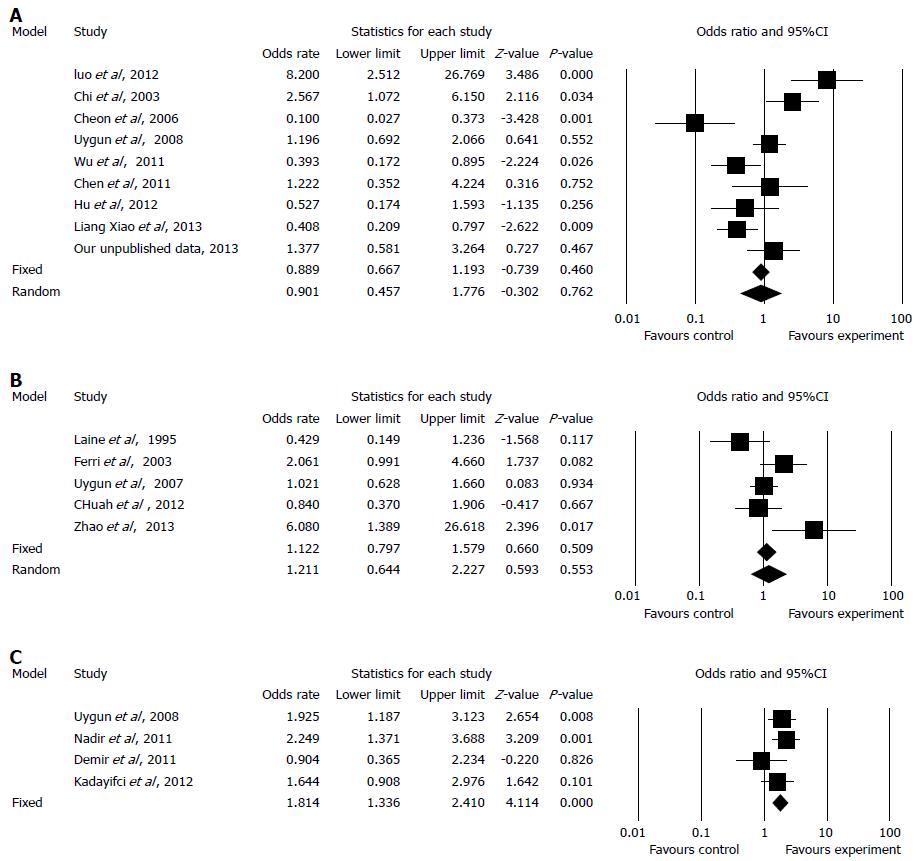

Quadruple treatment regimens containing amoxicillin and tetracycline vs other quadruple regimens of RCTs: Eight RCTs[20,23,37,38,41,46,47,56] and our unpublished data were included in the pooled analysis of quadruple treatment regimens (Table 1). The total H. pylori eradication rates were 78.1% (442/566) in the experimental group and 80.5% (714/887) in the control group by ITT analysis, and 84.5% (442/523) in the experimental group and 85.5% (714/835) in the control group by per-protocol (PP) analysis, respectively. The pooled OR was 0.90 (95%CI: 0.42-1.78) using a random effects model (I2 = 80.92%, P < 0.001; Figure 2A). When we omitted the study with the greatest weighting[40] from the analysis, the OR was 0.86 (95%CI: 0.38-2.00) using a random effects model (I2 = 82.73%, P < 0.001); when our unpublished data was omitted, the OR was 0.85 (95%CI: 0.40-1.83) by random effect model (I2 = 80.3%, P < 0.001).

| Ref. | Region | Publication | Participants | H. pylori infection Initial diagnosis ⁄re-checking | Inventions (duration) | Total (treatment/contrlo) | Follow-up (wk) | Eradication rate | Jadad scores |

| Luo[36], 2002 | China | Full text | NR1 | RUT/RUT | OBAT 7v OBCM 7 | 45/45 | 4 | 91% vs 56% | 1 |

| Chi et al[37], 2003 | Taiwan | Full text | Dyspeptic patients | Histology or culture/UBT | OBAT 7v OBAM 7 | 50/50 | 6 | 78% vs 58% | 3 |

| Cheon et al[20], 2006 | South Korea | Full text | Peptic ulcer | Histology or RUT or UBT/UBT | PBAT 7v PBMT 7 | 25/29 | 5 | 16% vs 66% | 2 |

| Uygun et al[40], 2008 | Tuekry | Full text | Non-ulcer dyspeptic patients | Histology/histology and RUT | LBAT 14 v LBAM or LBMT 14 | 100/200 | 60 d | 75% vs 73% | 2 |

| Wu et al[45], 2011 | Taiwan | Full text | NR | RUT and histology or culture or UBT | EBTA 7 v EBTM 7 | 58/62 | 8 | 62% vs 81% | 3 |

| Chen et al[46], 2011 | Chinese | Full text | Peptic ulcer and chronic gastritis | UBT/UBT | OATF 14/OBAC 14 | 60/60 | 4 | 92% vs 90% | 2 |

| Hu et al[23] , 2012 | Taiwan | Abstract | NR | NR/UBT | RATM 10, /RBTM, 10 | 46/47 | ≥ 4 | 83% vs 87% | 2 |

| Liang et al[55], 2013 | China | Full text | Functional dyspeptic patients and peptic ulcer | UBT/UBT | LBAT 14/LBTF, LBTM and LBAF 14 | 105/319 | 6 | 83.8% vs 91.5% | 3 |

| Our data1 | China | Duodenal peptic | RUT/UBT | RBAT 10/RBAC 10 | 77/75 | 4 | 85.7% vs 81.3% |

Because of significant evidence of heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analyses according to duration (7, 10, or 14 d), first- or second-line therapy, regimen in the experimental group, country, and publication language (Chinese or English).

Four RCTs[20,24,37,45] used a 7-d duration, in which the pooled eradication rates were 67.4% (120/178) by ITT and 72.7% (120/165) by PP in experimental groups. A 10-d regimen was used in one RCT[23] and our unpublished data, in which the pooled eradication rates were 84.6% (104/123) by ITT and 93.7% (104/111) by PP in groups treated with amoxicillin and tetracycline in combination. Fourteen-day regimens were employed in three RCTs[40,46,55], in which the pooled eradication rates were 82.3% (218/265) by ITT and 89.0% (218/245) by PP. The pooled OR were 0.97 (95%CI: 0.18-5.27) in the 7-d subgroup, 0.91 (95%CI: 0.36-2.31) in the 10-d subgroup, and 0.81 (95%CI: 0.37, 1.78) in the 14-d subgroup using a random effects model (I2 = 77.25%, P < 0.001).

Quadruple regimens with amoxicillin and tetracycline were used as first-line therapy in two RCTs[36,46] and our unpublished data, the pooled OR was 2.34 (95%CI: 0.74-7.42) using a random effects model(I2 = 70.29%, P = 0.035). When used as second-line therapy, as in six RCTs[20,23,37,40,45,55], the pooled OR was 0.59 (95%CI: 0.28-1.26) using a random effects model (I2 = 80.17%, P < 0.001).

In the subgroup of studies conducted in South Korea (included one RCT), the OR was 0.10 (95%CI: 0.03-0.37), which significantly differed from the other countries in which studies were conducted.

Results of other subgroup analyses demonstrated no statistically significant differences.

Triple therapy containing amoxicillin and tetracycline vs other regimens of RCTs: Five RCTs[17,21,24,33,50] compared the efficacies of triple regimens containing amoxicillin and tetracycline with other eradication regimens (Table 2). The pooled eradication rates were 68.8% (198/288, by ITT) and 72.5% (198/273, by PP) in the experimental group, and 66.7% (368/552) and 70.2% (368/524, by PP) in the control group. The pooled OR was 1.21 (95%CI: 0.64-2.28) using a random effects model (I2 = 63.50%, P = 0.027). The H. pylori eradication rate was slightly higher in the experimental group than in the control group, but this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 2B). In sensitivity analyses, when the study with the greatest weighting was omitted[21], the OR was 1.34 (95%CI: 0.64-3.43) using a random effects model (I2 = 71.89%, P = 0.014).

| Ref. | Region | Publication | Participants | H. pylori infection Initial diagnosis⁄re-checking | Inventions (duration) | Total (treatment/control) | Follow-up (wk) | Eradication rate by ITT | Jadad scores |

| Laine et al[33] 1995 | United States | Full text | Volunteers with H. pylori infection | UBT/UBT | OAT 14 vs OA 14 | 30/30 | 4 | 30% vs 50% | 3 |

| Perri et al[24], 2003 | Italy | Full text | NR | UBT/UBT | RBCAT 7 vs PLA or PBMT 7 | 60/120 | 4-6 | 85% vs 73.3% | 3 |

| Uygun et al[21], 2007 | Turkey | Full text | Non-ulcer Dyspeptic patients | Histology and UBT/UBT | RBCAT 14 vs RBCAC or RBCMT 14 | 100/200 | 6 | 58% vs 58% | 3 |

| Chuah et al[50], 2012 | Taiwan | Full text | Peptic ulcer disease or gastritis | RUT/RUT and histology or UBT | EAT 14 vs EALe 14 | 64/64 | 8 | 75% vs 78% | 3 |

| Zhao[17], 2013 | China | Full text | peptic ulcer and chronic gastritis | NR/UBT | PAT 7/PAC or PAM or PAF or PALe 7 | 34/138 | 30 d | 94% vs 73% | 1 |

Due to the evidence of heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analyses depending on duration (7 or 14 d), first- or second-line treatment, region (Asia, America, or Europe), publication language (Chinese or English), and control group regimen (dual, triple, or quadruple treatment).

Statistically significant differences were observed in the subgroups of 7-d treatment duration and Chinese publication language, in which the ORs were 2.95 (95%CI: 1.09-8.01) and 6.08 (95%CI: 1.39-26.62), respectively. In other subgroups, no statistically significant differences were noted.

Sequential treatment containing amoxicillin and tetracycline vs other regimens of RCTs: Four RCTs[41,44,47,51] were included the pooled analysis of sequential treatment (Table 3). The total eradication rates were 70.3% (317/451) in the experimental group and 57.3% (239/417) in the control group by ITT. The pooled OR was 1.81 (95%CI: 1.37-2.41) using a fixed-effects model (I2 = 5.17%, P = 0.367; Figure 2C). When we omitted the study with the greatest weighting on the result[41], the OR was 1.76 (95%CI: 1.24-2.50) using a fixed-effects model (I2 = 34.97%, P = 0.215).

| Ref. | Region | Publication | Participants | H. pylori infection Initial diagnosis⁄re-checking | Inventions (duration) | Total (treatment/contrlo) | Follow-up (wk) | Eradication rate and P | Jadad scores |

| Uygun et al[41], 2008 | Turkey | Full text | Non-ulcer dyspepsia | UBT and histology/UBT | PA 7-PMT 7 vs PAC 14 | 150/150 | 6 | 72% vs 58% | 3 |

| Nadir et al[44], 2011 | Turkey | Full text | Non-ulcer dyspepsia | Histology/UBT | LA 7-LMT 7 vs LAC 14 | 60/120 | 6 | 72% vs 54% | 2 |

| Demir et al[47], 2011 | Turkey | Full text | Non-ulcer Dyspeptic patients | UBT/UBT | PA 7-PMT 7 vs PAC 14 | 57/29 | 4 | 56% vs 59% | 3 |

| Kadayifci et al[51], 2012 | Turkey | Full text | Non-ulcer Dyspeptic patients | UBT and histology/UBT | LA 7-LCT 7 vs LA 7-LCM 7 | 100/100 | 4 | 72% vs 61% | 2 |

Among the 17 RCTs and our unpublished data included in the meta-analysis, 14 RCTs and our data provided information concerning adverse effects. The incidences of total adverse effects were 12.4% (112/898) in the experimental groups and 18.7% (229/1225) in the control groups. Diarrhea appeared in 23 of 752 patients in experimental groups and 31 of 1028 patients in control groups, abdominal pain occurred in 14 of 582 patients in experimental groups and 24 of 798 patients in control groups, and nausea occurred in 26 of 737 patients in experimental groups and 55 of 953 patients in control groups. The incidence of adverse effects demonstrated no significant differences.

To interpret heterogeneity in our meta-analysis, we performed meta-regression analyses. The results indicated that publication language, regimens of treatment in experimental and control groups, and assessment of first- vs second-line therapy were the major reasons for heterogeneity in the meta-analysis of quadruple therapies. The main causes of heterogeneity in the meta-analysis of triple therapies were duration, study quality, and publication language.

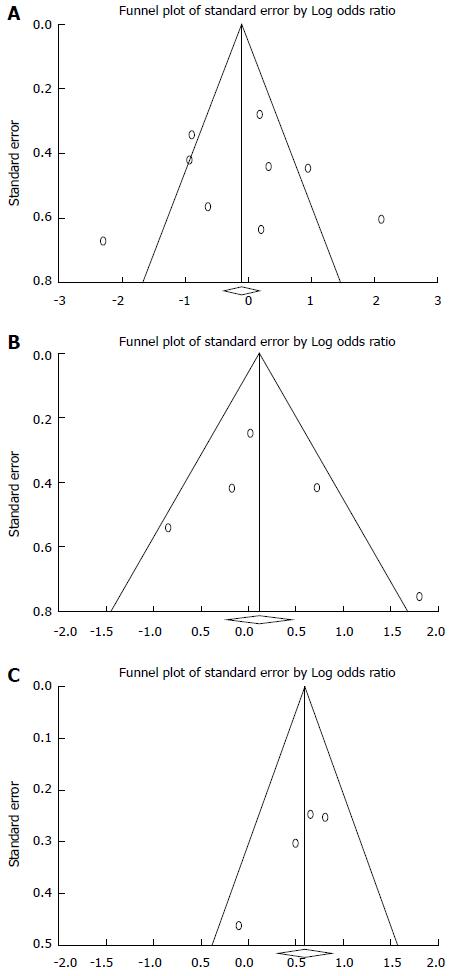

The funnel plots of meta-analyses of both quadruple and triple therapy studies were symmetrical, and Egger’s test and Begg’s test indicated no statistically significant differences. The funnel plot of sequential treatment was symmetrical; however, while Begg’s test indicated no statistically significant difference, Egger’s test demonstrated a statistically significant difference (P = 0.042; Figure 3).

Efficacy of first-line treatment with amoxicillin and tetracycline: Five non-RCT trials examined the combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline used as first-line anti-H. pylori treatment. Graham et al[22] reported a poor eradication rate (43%, 7/16). A study conducted by Sezgin et al[38] suggested that sequential therapy consisting of PPI-amoxicillin followed by PPI-metronidazole-tetracycline achieved an unsatisfactory eradication rate (50%, 15/30, by ITT). Ataseven et al[43] reported that sequential treatment with pantoprazole and amoxicillin for the first 7 d followed by pantoprazole, metronidazole, and tetracycline for the following 7 d achieved an unacceptable eradication rate (57.9%, 22/38) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Lobo et al[19] compared treatment consisting of omeprazole, amoxicillin, and tetracycline (group A) with a regimen including bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline (group B) for H. pylori eradication, and observed H. pylori eradication rates of 59% (10/17) in group A and 65% (17/26) in group B, with a non-significant difference of -6% (χ2 = 0.19). However, a study conducted by Uygun et al[53] reported that a modified sequential therapy consisting of pantoprazole, bismuth, and amoxicillin for the first seven days followed by pantoprazole, bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline for the remaining seven days achieved an acceptable eradication rate (81.0%, 115/142) by ITT (Table 4).

| Ref. | Region | Publication | Participants | H. pylori infection Initial diagnosis⁄re-checking | Inventions (duration) | Cases | Follow-up (wk) | Eradication rate by ITT | First or second or three line therapy1 |

| Graham et al[22], 1993 | United States | Full text | Peptic ulcer | UBT and histology/UBT and histology | BAT 14 | 16 | 4 | 43% | 1 |

| Lobo et al[19], 1994 | United Kingdom | Full text | NR | histology or culture /histology and culture | OAT 21 vs BT 28+M 14 | 17/26 | 4 | 58% vs 65% | 1 |

| Auriemma et al[34], 2001 | Italy | Abstract | NR | NR/UBT | OAT 7 | 63 | NR | 77.3% | 2 |

| Perri et al[35], 2002 | Italy | Full text | Dyspepsia | Histology and RUT/UBT | LAT 7 vs RBCAT 7 vs LAD 7 | 89/88/87 | 4-6 | 35% vs 20% vs 36% | 1 |

| Cammarota et al[25], 2004 | Italy | Full text | NR | Culture/UBT | OBTA 7 | 89 | 8 | 91% | 3 |

| Sezgin et al[38],2007 | Turkey | Full text | Dyspepsia or peptic ulcer | Histology and RUT and UBT/UBT | PA 7-PMT 7 | 32 | 4 | 50% | 1 |

| Buzás et al[39], 2008 | Hungary | Full text | Duodenal ulcer | histology and RUT/UBT | PATN 14 vs PATB 14 | 22/19 | 6 | 62% vs 55% | 3 |

| Akyildiz et al[42], 2009 | Turkey | Full text | NR | Histology and RUT/UBT | RBCAT 14/RBCAT 14 | 58/57 | 6 | 34.5% vs 36.8% | 1 |

| Cetinkaya et al[26], 2010 | Turkey | Full text | Nonulcer dyspepsia | Histology/UBT | PA 5- PTM 9 vs PA5-PATM 9 | 56/56 | 6 | 82%/79% | 1 |

| Ataseven et al[43], 2010 | Turkey | Full text | 2-type Diabetes mellitus with H. pylori | Histology and RUT/UBT | PA 7-PTM 7 | 38 | 4 | 58% | 1 |

| Zhang[49], 2012 | China | Full text | NR | RUT and UBT/UBT | EBAT | 120 | 1 mo | 93% | 2 |

| Tursi1 et al[52], 2012 | Italy | Full text | peptic ulcer or gastritis or duodenitis | NR/RUT or UBT | PPI+A 5 - PPI+Le+T 5 | 119 | 1 mo | 67% | 3 |

| Uygun et al[53], 2012 | Turkey | Full text | nonulcerdyspepsia | Histology/UBT | PBA 7 - PBTM 7 | 142 | 45 d | 81% | 1 |

| Kadayifci et al[48], 2012 | Turkey | Full text | non-ulcerdyspepsia | Histology and UBT/UBT | EBAT 14/EATM 14 | 100/100 | 6 | 79%/74% | 1 |

| Liou et al[54], 2013 | Taiwan | Full text | NR | UBT or two of RUT, histology and culture | EA 7- EMC 7 vs EA 7-EMT 7 vs EA 7 - EMLe 7 | 19/65/51 | ≥ 6 | 80%/71%/92% | 3 |

Four RCTs compared various combinations of amoxicillin and tetracycline or doxycycline. In one study comparing the combination of tetracycline and amoxicillin with that of doxycycline and amoxicillin, the H. pylori eradication rates were 34.5% (20/57) and 36.8% (21/58), respectively[42]. Another study compared different sequential therapies involving the combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline (5 d vs 14 d of amoxicillin) during anti-H. pylori treatment and found a non-significant difference of 3.51%; interestingly, 14-d amoxicillin regimens obtained a lower eradication rate than 5-d regimens[26]. One RCT compared a quadruple regimen (consisting of bismuth, esomeprazole, tetracycline, and amoxicillin) with concomitant therapy (with esomeprazole, tetracycline, metronidazole, and amoxicillin) in patients naïve to H. pylori treatment, and observed H. pylori eradication rates of 79% in the quadruple therapy group and 74% in the concomitant therapy group[48]. Perri et al[35] compared three different triple regimens with lansoprazole or RBC plus amoxicillin and tetracycline or doxycycline and observed that all treatments achieved poor H. pylori eradication rates.

Efficacy of second-line regimens containing amoxicillin and tetracycline: Two non-RCT trials investigated the combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline for second-line anti-H. pylori treatment. Auriemma et al[34] reported an H. pylori eradication rate of 77.7% (49/63) after second-line therapy with omeprazole, amoxicillin, and tetracycline in patients. Zhang reported that a quadruple regimen consisting of bismuth, amoxicillin, tetracycline, and esomeprazole achieved a satisfactory H. pylori eradication rate (93.3%, 112/120)[49].

Efficacy of third-line regimens containing amoxicillin and tetracycline: Regimens containing amoxicillin and tetracycline were used as a third-line anti-H. pylori treatment in four trials. Buzás et al[39] conducted a trial, in which, among patients who received quadruple therapy containing amoxicillin and tetracycline, the eradication rate was 56.1% (23/41) by ITT. Cammatora et al[25] reported that quadruple treatment consisting of bismuth, omeprazole, amoxicillin, and doxycycline achieved a satisfactory eradication rate of 91.0% (81/89) in patients in whom H. pylori isolates were susceptible to amoxicillin and tetracycline. Tursi et al[52] reported that among 119 patients who received sequential therapy with a standard dosage of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) plus 1 g amoxicillin for the first 5 d, followed by the standard dosage PPI, 500 mg levofloxacin and 500 mg tetracycline, a 67.23% eradication rate (80/119) by ITT was achieved. Liou et al[54] conducted a multi-center trial in which 109 patients who failed second-line therapies underwent sequential treatment with esomeprazole plus amoxicillin for the first 7 d, followed by esomeprazole and metronidazole plus clarithromycin or levofloxacin or tetracycline, according to genotypic resistance, for another 7 d. Their eradication rates were 78.5% in the clarithromycin group, 92.2% in the levofloxacin group, and 71.4% in the tetracycline group.

With antibiotic resistance rates of H. pylori rapidly increasing, the efficacies of conventional triple regimens are diminishing, and approximately 5%-35% of patients fail to achieve eradication with first- or second-line therapy[56]. Therefore, investigators are looking for a replacement for triple regimens. Some regimens, such as quadruple therapy with bismuth, sequential treatment, and concomitant therapy, have been considered as the substitution for triple regimens for H. pylori eradication treatment. However, their efficacies may be impaired by the increasing prevalence of antibiotic-resistant H. pylori. The combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline is very attractive because of its low cost, low resistance rate, and safety[8]. Hence, the combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline may be a suitable substitute for triple regimens in the treatment of H. pylori infection.

The current meta-analysis of RCTs indicates that regimens involving amoxicillin and tetracycline were not inferior to other regimens for the eradication of H. pylori infection.

In the meta-analysis of quadruple treatments with amoxicillin and tetracycline, 10- or 14-d quadruple regimens could achieve acceptable or good eradication rates, but the effectiveness of a 7-d quadruple regimen was unsatisfactory. These results are in line with most previous studies[57-59]. According to subgroup analyses, the OR of studies published in Chinese was greater than those published in English (3.2 vs 0.63). Although the quality of the studies included in our meta-analysis was not consistently high and some limitations may exist in study design that could affect the results, the 10- or 14-d quadruple regimen with a combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline may be considered as one option for the treatment of H. pylori infection[55]. Our results also generated additional information for the further study of regimens, including amoxicillin and tetracycline to treat H. pylori infection.

In our meta-analysis of triple therapy containing amoxicillin and tetracycline for H. pylori infection, the pooled eradication rate was 68.8% by ITT (less than an acceptable level). Subgroup analyses indicated significant differences associated with a 7-d regimen and publication in Chinese. These differences may be the result of the low quality of the studies included in these subgroups, rather than reflecting the actual treatment outcomes. Further study, with sufficient sample size and good design, may be necessary to corroborate the efficacy of the treatment regimen. Notably, the 7-d triple regimen with a combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline obtained a higher eradication rate than 14-d triple regimens. The reasons underlying this conflicting finding compared to the results of quadruple-therapy regimens may be the lower number of studies employing triple-therapy 7-d regimens (two RCTs) and the different populations included in these studies. Furthermore, some non-RCTs reported that 7-or 14-d triple regimens with amoxicillin and tetracycline achieved poor eradication rates[22,34,35]. In summary, triple therapy with a combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline may not be suitable for H. pylori eradication due to the lower eradication rate.

Several novel regimens for H. pylori infection have been used by investigators in various countries as a more effective alternative to traditional triple therapies, including sequential therapy, concomitant therapy, and hybrid therapy[56,60,61]. Sequential therapy with amoxicillin and tetracycline has also garnered the attention of some investigators[61]. Our meta-analysis that found the eradication rate of sequential therapy to be higher than that of control treatment(70.3% vs 57.3%, P < 0.001). These results are consistent with one study[51]. However, the pooled eradication rate was below an acceptable level. Therefore, sequential therapy including a combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline may not be an appropriate treatment for H. pylori infection.

Earlier studies not included in the meta-analysis reported that in combination with PPI or RBC, amoxicillin and tetracycline achieve poor eradication rates[20,22,42], but they had some limitations: small sample size, no control groups, and low quality of the studies.

Failure to eradicate H. pylori through first-or second-line treatment remains a challenge. The Maastricht IV consensus report recommended that treatment after failure of second-line therapy should be guided by antimicrobial susceptibility testing[15]. The combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline may be one option due to the low resistance of H. pylori to amoxicillin and tetracycline[7,8].

To diminish bias, the study selection, data extraction, and evaluation of study quality were performed by two reviewers. Most of the clinical trials in English and Chinese that used amoxicillin and tetracycline to treat H. pylori were identified by the current systemic review and meta-analysis. We comprehensively analyzed the efficacy of the combination of tetracycline and amoxicillin for anti-H. pylori treatment. Meta-regression and sensitivity analyses support the reliability of our meta-analysis outcomes.

This study had several limitations. First, most of the studies included in our meta-analysis had problems with concealment of allocation and blinding, which could have affected our results, although we performed sensitivity analysis to verify the reliability of our findings. Second, some obvious heterogeneity was present in the meta-analysis, although we conducted subgroup analyses and meta-regression analyses to decrease its effects. Third, bias may exist across published languages, and thus our meta-analysis probably does not reflect all the outcomes of the combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline. Finally, we requested unpublished data from some authors but received no response, and introduction of bias on that basis is possible.

In conclusion, available data suggest that the combination of amoxicillin and tetracycline for H. pylori infection does not appear to be inferior to other regimens whether used as a first, second, or third-line treatment. Both 10- and 14-d regimens involving a combination of tetracycline and amoxicillin can provide an acceptable eradication rate, but further investigation may be necessary to confirm the efficacy of the combination.

Many studies have shown that Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) resistance to amoxicillin and tetracycline is rare; in theory, regimens combining amoxicillin and tetracycline should provide an excellent eradication rate for H. pylori infection.

Some controversies exist regarding the ability of combined amoxicillin and tetracycline to eradicate H. pylori because the combination of these two agents may appear antagonistic despite H. pylori having high susceptibility to both amoxicillin and tetracycline in vitro. But the similar combination of clarithromycin and amoxicillin has commonly been used for H. pylori infection for decades. Is a regimen containing tetracycline and amoxicillin suitable for H. pylori Infection?

This was the first systemic review and meta-analysis comparing the efficacy of combination with amoxicillin and tetracycline with other pre-existing regimens for eradication H. pylori.

Available data suggest that the effectiveness of regimens employing amoxicillin and tetracycline for H. pylori eradication may be not inferior to other regimens, and 10- or 14-d quadruple regimens with amoxicillin and tetracycline can achieve acceptable eradication rates and may be suitable for the treatment of H. pylori infection.

The combination with amoxicillin and tetracycline referred in this systemic review and meta-analysis is one study arm including both tetracycline and amoxicillin for eradication of H. pylori.

The authors conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials with treatment including both tetracycline and amoxicillin vs other regimens for eradication of H. pylori, and it would provide clinical practice guidelines for successful and cheap eradication. General impression, it is a nice article, and the study has some interesting new ideals.

P- Reviewer: Bao Z S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Calvet X, Ramírez Lázaro MJ, Lehours P, Mégraud F. Diagnosis and epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2013;18 Suppl 1:5-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Eid R, Moss SF. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:65-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McColl KE. Clinical practice. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1597-1604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 529] [Cited by in RCA: 550] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Current European concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. The Maastricht Consensus Report. European Helicobacter Pylori Study Group. Gut. 1997;41:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 679] [Cited by in RCA: 674] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, Bazzoli F, El-Omar E, Graham D, Hunt R, Rokkas T, Vakil N, Kuipers EJ. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772-781. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Mendonça S, Ecclissato C, Sartori MS, Godoy AP, Guerzoni RA, Degger M, Pedrazzoli J. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori resistance to metronidazole, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, tetracycline, and furazolidone in Brazil. Helicobacter. 2000;5:79-83. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Vilaichone RK, Yamaoka Y, Shiota S, Ratanachu-ek T, Tshering L, Uchida T, Fujioka T, Mahachai V. Antibiotics resistance rate of Helicobacter pylori in Bhutan. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5508-5512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Megraud F, Coenen S, Versporten A, Kist M, Lopez-Brea M, Hirschl AM, Andersen LP, Goossens H, Glupczynski Y. Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics in Europe and its relationship to antibiotic consumption. Gut. 2013;62:34-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 653] [Cited by in RCA: 632] [Article Influence: 52.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 9. | Megraud F. Helicobacter pylori and antibiotic resistance. Gut. 2007;56:1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Graham DY, Fischbach L. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the era of increasing antibiotic resistance. Gut. 2010;59:1143-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 652] [Cited by in RCA: 736] [Article Influence: 49.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Malfertheiner P, Bazzoli F, Delchier JC, Celiñski K, Giguère M, Rivière M, Mégraud F. Helicobacter pylori eradication with a capsule containing bismuth subcitrate potassium, metronidazole, and tetracycline given with omeprazole versus clarithromycin-based triple therapy: a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377:905-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 350] [Cited by in RCA: 373] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Raj JM, Raj SM. Concern about the efficacy of clarithromycin containing standard triple therapy in the eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection in Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 2012;67:547. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Venerito M, Krieger T, Ecker T, Leandro G, Malfertheiner P. Meta-analysis of bismuth quadruple therapy versus clarithromycin triple therapy for empiric primary treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Digestion. 2013;88:33-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Seddik H, Ahid S, El Adioui T, El Hamdi FZ, Hassar M, Abouqal R, Cherrah Y, Benkirane A. Sequential therapy versus standard triple-drug therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a prospective randomized study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69:1709-1715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646-664. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Fock KM, Katelaris P, Sugano K, Ang TL, Hunt R, Talley NJ, Lam SK, Xiao SD, Tan HJ, Wu CY. Second Asia-Pacific Consensus Guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1587-1600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 420] [Cited by in RCA: 427] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Zhao X. Efficacy of amoxicillin combined with different antibiotic in anti Helicobacter pylori treatment. Nanjing Yikedaxue Xiebao (. Ziran Kexueban). 2013;33:255-256. |

| 18. | Vilaichone RK, Gumnarai P, Ratanachu-Ek T, Mahachai V. Nationwide survey of Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance in Thailand. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;77:346-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lobo AJ, McNulty CA, Uff JS, Dent J, Eyre-Brook IA, Wilkinson SP. Preservation of gastric antral mucus is associated with failure of eradication of Helicobacter pylori by bismuth, metronidazole and tetracycline. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8:181-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cheon JH, Kim SG, Kim JM, Kim N, Lee DH, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Combinations containing amoxicillin-clavulanate and tetracycline are inappropriate for Helicobacter pylori eradication despite high in vitro susceptibility. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1590-1595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Uygun A, Kadayifci A, Yesilova Z, Ates Y, Safali M, Ilgan S, Bagci S, Dagalp K. Poor efficacy of ranitidine bismuth citrate-based triple therapies for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2007;26:174-177. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Graham DY, Lew GM, Ramirez FC, Genta RM, Klein PD, Malaty HM. Short report: a non-metronidazole triple therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection--tetracycline, amoxicillin, bismuth. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1993;7:111-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hu H, Hsu P, Chuah S, Liu M, Kuo F, Kuo C, Wu D. Su1706 Amoxicillin in Replacement for Bismuth Subcitrate Offers Similar Helicobacter pylori Eradiation Response in Second-Line Rabeprazole-Based Quadruple Therapy. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:485. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Perri F, Festa V, Merla A, Barberani F, Pilotto A, Andriulli A. Randomized study of different ‘second-line’ therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection after failure of the standard ‘Maastricht triple therapy’. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:815-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cammarota G, Martino A, Pirozzi G, Cianci R, Branca G, Nista EC, Cazzato A, Cannizzaro O, Miele L, Grieco A. High efficacy of 1-week doxycycline- and amoxicillin-based quadruple regimen in a culture-guided, third-line treatment approach for Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:789-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cetinkaya ZA, Sezikli M, Güzelbulut F, Coşgun S, Düzgün S, Kurdaş OO. Comparison of the efficacy of the two tetracycline-containing sequential therapy regimens for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori: 5 days versus 14 days amoxicillin. Helicobacter. 2010;15:143-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13930] [Cited by in RCA: 13351] [Article Influence: 834.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12275] [Cited by in RCA: 12886] [Article Influence: 444.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:377-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5177] [Cited by in RCA: 5935] [Article Influence: 219.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Li S, Xu K. Comparative study of different treatment of duodenal ulcer. Jiangsu Yiyao. 1995;21:440-442. |

| 31. | Zhou X. Therapeutic effect of levofloxacin on peptic ulcer relapse in the observation. Zhongwai Yixue Yanjiu. 2012;10:45-46. |

| 32. | Akyildiz M, Akay S, Musoglu A, Tuncyurek M, Tekin F, Aydin A. The efficacy of ranitidine bismuth citrate, amoxicillin, and doxycycline or tetracycline regimens as a first-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Helicobacter. 2007;12:433. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Laine L, Stein C, Neil G. Limited efficacy of omeprazole-based dual and triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori: a randomized trial employing “optimal” dosing. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1407-1410. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Auriemma L, Signorelli S. [The role of tetracycline in the retreatment after Helicobacter pylori eradication failure]. Minerva Med. 2001;92:145-149. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Perri F, Festa V, Merla A, Quitadamo M, Clemente R, Andriulli A. Amoxicillin/tetracycline combinations are inadequate as alternative therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2002;7:99-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Luo K. Clinical study of lizhuweisanlian on the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Huaxia Yixue. 2002;15:166-167. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 37. | Chi CH, Lin CY, Sheu BS, Yang HB, Huang AH, Wu JJ. Quadruple therapy containing amoxicillin and tetracycline is an effective regimen to rescue failed triple therapy by overcoming the antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:347-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sezgin O, Altintaş E, Nayir E, Uçbilek E. A pilot study evaluating sequential administration of a PPI-amoxicillin followed by a PPI-metronidazole-tetracycline in Turkey. Helicobacter. 2007;12:629-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Buzás GM, Széles I. Interpretation of the 13C-urea breath test in the choice of second- and third-line eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:108-114. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Uygun A, Ozel AM, Yildiz O, Aslan M, Yesilova Z, Erdil A, Bagci S, Gunhan O. Comparison of three different second-line quadruple therapies including bismuth subcitrate in Turkish patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia who failed to eradicate Helicobacter pylori with a 14-day standard first-line therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:42-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Uygun A, Kadayifci A, Yesilova Z, Safali M, Ilgan S, Karaeren N. Comparison of sequential and standard triple-drug regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a 14-day, open-label, randomized, prospective, parallel-arm study in adult patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. Clin Ther. 2008;30:528-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Akyildiz M, Akay S, Musoglu A, Tuncyurek M, Aydin A. The efficacy of ranitidine bismuth citrate, amoxicillin and doxycycline or tetracycline regimens as a first line treatment for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:53-57. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 43. | Ataseven H, Demir M, Gen R. Effect of sequential treatment as a first-line therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in patients with diabetes mellitus. South Med J. 2010;103:988-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Nadir I, Yonem O, Ozin Y, Kilic ZM, Sezgin O. Comparison of two different treatment protocols in Helicobacter pylori eradication. South Med J. 2011;104:102-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Wu DC, Hsu PI, Tseng HH, Tsay FW, Lai KH, Kuo CH, Wang SW, Chen A. Helicobacter pylori infection: a randomized, controlled study comparing 2 rescue therapies after failure of standard triple therapies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2011;90:180-185. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 46. | Chen X, Wang L, Zheng Z, Zhou L. The efficacy and cost evaluation of two different regimens for eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Guiyang Yixueyuan Xuebao. 2011;36:630-631. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 47. | Demir M, Ataseven H. The effects of sequential treatment as a first-line therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Tur J Med Sci. 2011;41:427-433. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kadayifci A, Uygun A, Polat Z, Kantarcioğlu M, Kılcıler G, Başer O, Ozcan A, Emer O. Comparison of bismuth-containing quadruple and concomitant therapies as a first-line treatment option for Helicobacter pylori. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2012;23:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Zhang G. Effect of tetracycline quadruple second-line therapy for Helicobacter pylori after first eradication failure. Zhongguo Yiyao Zhinan. 2012;10:154-155. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 50. | Chuah SK, Hsu PI, Chang KC, Chiu YC, Wu KL, Chou YP, Hu ML, Tai WC, Chiu KW, Chiou SS. Randomized comparison of two non-bismuth-containing second-line rescue therapies for Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2012;17:216-223. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 51. | Kadayifci A, Uygun A, Kilciler G, Kantarcioglu M, Kara M, Ozcan A, Emer O. Low efficacy of clarithromycin including sequential regimens for Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2012;17:121-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Tursi A, Picchio M, Elisei W. Efficacy and tolerability of a third-line, levofloxacin-based, 10-day sequential therapy in curing resistant Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2012;21:133-138. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Uygun A, Ozel AM, Sivri B, Polat Z, Genç H, Sakin YS, Çelebi G, Uygur-Bayramiçli O, Erçin CN, Kadayifçi A. Efficacy of a modified sequential therapy including bismuth subcitrate as first-line therapy to eradicate Helicobacter pylori in a Turkish population. Helicobacter. 2012;17:486-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Liou JM, Chen CC, Chang CY, Chen MJ, Fang YJ, Lee JY, Chen CC, Hsu SJ, Hsu YC, Tseng CH. Efficacy of genotypic resistance-guided sequential therapy in the third-line treatment of refractory Helicobacter pylori infection: a multicentre clinical trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:450-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Liang X, Xu X, Zheng Q, Zhang W, Sun Q, Liu W, Xiao S, Lu H. Efficacy of bismuth-containing quadruple therapies for clarithromycin-, metronidazole-, and fluoroquinolone-resistant Helicobacter pylori infections in a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:802-7.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | O’Connor A, Molina-Infante J, Gisbert JP, O’Morain C. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection 2013. Helicobacter. 2013;18 Suppl 1:58-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Chung JW, Lee JH, Jung HY, Yun SC, Oh TH, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee GH, Kim JH. Second-line Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized comparison of 1-week or 2-week bismuth-containing quadruple therapy. Helicobacter. 2011;16:289-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Sun Q, Liang X, Zheng Q, Liu W, Xiao S, Gu W, Lu H. High efficacy of 14-day triple therapy-based, bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for initial Helicobacter pylori eradication. Helicobacter. 2010;15:233-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Lee BH, Kim N, Hwang TJ, Lee SH, Park YS, Hwang JH, Kim JW, Jeong SH, Lee DH, Jung HC. Bismuth-containing quadruple therapy as second-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection: effect of treatment duration and antibiotic resistance on the eradication rate in Korea. Helicobacter. 2010;15:38-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Zullo A, Rinaldi V, Winn S, Meddi P, Lionetti R, Hassan C, Ripani C, Tomaselli G, Attili AF. A new highly effective short-term therapy schedule for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:715-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Chitsaz E. Concomitant, sequential, and hybrid therapy for Helicobacter pylori: which one is the correct answer? Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37:e125-e126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |