Published online Feb 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i7.2214

Peer-review started: June 26, 2014

First decision: July 9, 2014

Revised: August 15, 2014

Accepted: September 29, 2014

Article in press: September 30, 2014

Published online: February 21, 2015

Processing time: 230 Days and 11.8 Hours

Acute hepatic failure due to hepatitis B virus (HBV) can occur both during primary infection as well as after reactivation of chronic infection. Guidelines recommend considering antiviral therapy in both situations, although evidence supporting this recommendation is weak. Since HBV is not directly cytopathic, the mechanism leading to fulminant hepatitis B is thought to be primarily immune-mediated. Therefore, immunosuppression combined with antiviral therapy might be a preferred therapeutic intervention in acute liver failure in hepatitis B. Here we report our favourable experience in three hepatitis B patients with fulminant hepatic failure who were treated by combining high-dose steroid therapy with standard antiviral treatment, which resulted in a rapid improvement of clinical and liver parameters.

Core tip: In the reported cases we describe our positive experience with combined glucocorticoid and nucleotide analogue therapy in two cases of severe reactivations of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and in one case of acute fulminant HBV infection. Rapid improvement of liver parameters and virological response was obtained in all three cases. Thus, the reported data emphasize the need for the further assessment of this therapeutic strategy and for the development of systematic clinical trials.

- Citation: Bockmann JH, Dandri M, Lüth S, Pannicke N, Lohse AW. Combined glucocorticoid and antiviral therapy of hepatitis B virus-related liver failure. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(7): 2214-2219

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i7/2214.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i7.2214

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is one of the most common infectious diseases worldwide. However, acute and fulminant hepatitis B are relatively uncommon[1]. Acute hepatic failure due to HBV infection is thought to be mostly caused by a strong immune response raised against the virus and does not seem to be primarily related to high viral load or the degree of active viral replication. Indeed, many immunotolerant HBV carriers may have very high viremia levels but nearly normal levels of liver enzymes and no or only minimal inflammatory activity in the liver[2]. Thus, acute liver failure appears to be rather the expression of an overwhelming immune reactivity against the virus. This clinical picture can be observed particularly in patients who are chronic HBV carriers and have received chemotherapy, including treatment with rituximab, without antiviral prophylaxis[3]. During the phase of chemotherapy hematopoietic side effects suppress the immune system and especially rituximab was shown to induce B-cell depletion and loss of virus immune control, thus allowing the increase of viral replication and intrahepatic spread[4,5]. After discontinuing immunosuppressive chemotherapy, the immune system generally recovers and as a consequence of the expected immune reconstitution an exaggerated antiviral immune response can develop, leading to rapid destruction of the infected hepatocytes. Both the strength of the immune response and the high rate of infected liver cells set the stage for the occurrence of hepatic failure.

Primary HBV infection can also cause fulminant hepatitis in patients with a marked immune responsiveness to the virus, while infection of immune-compromised hosts generally leads to the failure of virus immune control without evidence of acute hepatic damage.

The availability of nucleoside or nucleotide analogues (NUCs) as effective antiviral therapy has led to their application in patients with fulminant viral hepatitis B infection, and examples with apparently favourable effect have been reported[6,7]. Such observations and the lack of other clinical studies exploring additional therapeutic regimens has led to the recommendation in the 2012 EASL practise guideline to give antiviral therapy to patients with fulminant hepatitis B using NUCs with high resistance barrier such as tenofovir or entecavir, even if both drugs have not been studied systematically for this indication[8]. However, even these effective antiviral drugs generally need some weeks before HBV-DNA becomes undetectable and therefore they may be too slow to influence the clinical course of fulminant hepatic failure in hepatitis B. In view of the immunopathogenetic process involved in fulminant hepatitis B we reasoned that dampening the overwhelming antiviral immune response might actively contribute to the effectiveness of treatment, and report here our favourable experience in the first three patients managed by combining high-dose steroid therapy with standard anti-viral treatment.

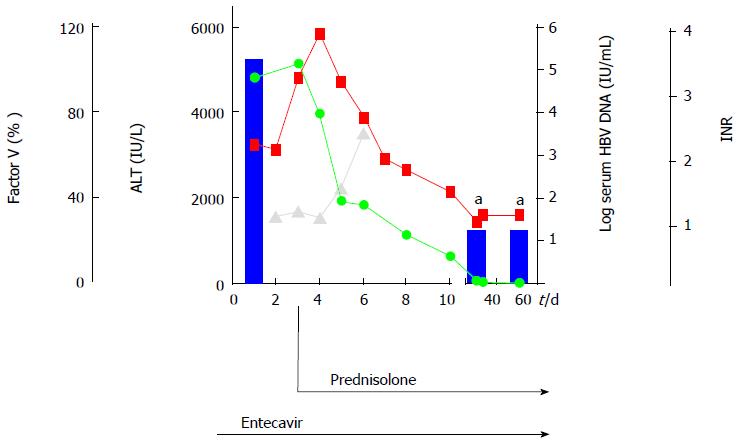

A 32-year-old woman (patient N.1) was admitted with fatigue, vomiting, jaundice and pain in the right upper abdomen. Biochemical and clinical evaluation provided criteria of acute liver failure (AST: 5104 IU/L, ALT: 4826 IU/L, total bilirubin: 7.2 mg/dL, international normalized ratio: 2.18), and encephalopathy grade I, history of childbirth with blood transfusions 4 years earlier with negative HBsAg status. Acute liver failure was defined by an international normalized ratio of greater than 1.5 and any degree of encephalopathy. Briefly, virological analysis showed evidence of acute HBV infection (HBsAg-pos, anti-HBcAg-IgM-pos, viral load 2 × 105 IU/mL) and diffuse damage of liver parenchyma determined by ultrasound. While antiviral therapy was immediately started with 1 mg entecavir/d, further increase of international normalized ratio (3.21) was observed throughout the following days. Thus, high-dose steroid therapy was added after 3 d of antiviral treatment. Prednisolone treatment was started intravenously (i.v.) with 1.5 mg/kg body weight. Transaminases and international normalized ratio decreased within 7 d, while HBsAg seroconversion followed after 9 wk, as summarized in Figure 1. Two days after the start of glucocorticoid therapy dropping of transaminases was observed and the prednisolone dose was reduced to 60 mg/d per os (p.o.) with further reductions of 10 mg/wk to a dose of 20 mg/d, thereafter reductions of 5 mg/wk (Table 1).

| Before treatment | After treatment | |||||

| Patient 1 | Patient 2A | Patient 2B | Patient 1 | Patient 2A | Patient 2B | |

| Albumin (g/L) | 35 | 28 | 33 | 38 | 24 | 37 |

| ASAT (U/L) | 5463 | 1310 | 2306 | 13 | 68 | 74 |

| ALAT (U/L) | 5144 | 1832 | 3678 | 14 | 9 | 83 |

| GGT (U/L) | 77 | 94 | 111 | 24 | 32 | 137 |

| AP (U/L) | 157 | 144 | 99 | 56 | 204 | 122 |

| pH | 7.42 | - | 7.43 | 7.44 | 7.37 | 7.42 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 2.5 | - | 2.8 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 11.4 | 26.1 | 29.8 | 0.7 | 9.7 | 1.2 |

| International normalized ratio | 2.18 | 1.81 | 1.92 | 1.07 | 1.27 | 1.27 |

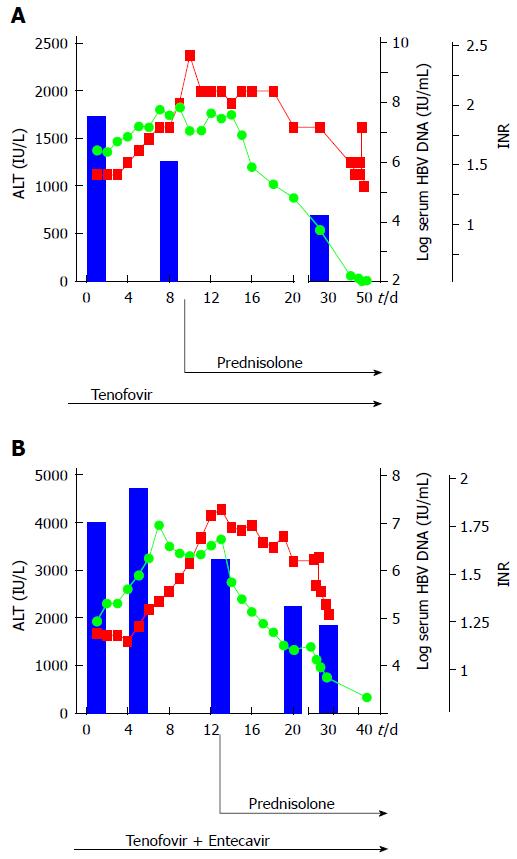

A 66-year-old woman (patient N.2a) was admitted with fatigue, nausea and jaundice (AST: 1006 IU/L, ALT: 1368 IU/L, total bilirubin: 15.8 mg/dL, international normalized ratio: 1.34). Nine months earlier, treatment of low-malignant B-cell lymphoma was stopped (marginal zone lymphoma, stage IIA) after 6 cycles of rituximab and bendamustin. At this time, the HBsAg status was unknown. At presentation virological evaluation showed active HBV infection (HBsAg-pos, HBeAg-neg, viral load 4 × 107 IU/mL). As shown in Figure 2A, antiviral therapy was started by administering tenofovir (245 mg/d). Due to further deterioration of hepatic synthetic function with increase of transaminases and international normalized ratio within the first 9 d of antiviral treatment, prednisolone therapy was subsequently started with 1mg/kg body weight (i.v.). As depicted in Figure 2A, international normalized ratio and transaminases dropped rapidly, while a clear reduction of viral load (2 × 104 IU/mL) occurred after 4 wk. After 2 d of glucocorticoid treatment, the dose was reduced to 60 mg/d p.o. with reductions of 10 mg/wk analogous to the treatment of patient N.1.

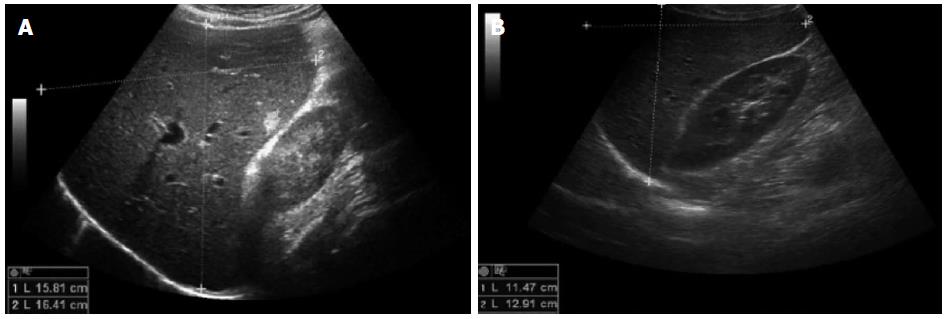

A 57-year-old man (patient N.2b) presented with fatigue, jaundice and mild cognitive dysfunction. Biochemical and clinical evaluation provided criteria of subacute liver failure at hospital admission (ALT: 1933 IU/L, total bilirubin: 4.9 mg/dL; international normalized ratio: 1.17, grade I encephalopathy). In medical history, chronic Hepatitis B virus infection was diagnosed 9 mo earlier in the course of a HBV screening prior to R-CHOP therapy due to the identification of a high-grade malignant diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (activated B-cell-like, stage IIIS). Thus, antiviral prophylaxis based on the use of the nucleotide analogue tenofovir was initiated. One month after cessation of R-CHOP, the patient stopped prophylactic antiviral tenofovir treatment for unknown reasons. A massively increased viral load (HBV DNA 6 × 107 IU/mL), hepatomegaly in ultrasound, in combination with an increasing international normalized ratio and the clinical symptoms strengthened the diagnosis of liver failure due to HBV reactivation. Despite restarting immediately antiviral therapy with tenofovir, the patient’s conditions deteriorated, so that antiviral treatment was extended with the nucleoside analogue entecavir. However, a further increase of liver transaminases and progressive liver failure developed, therefore liver transplantation was discussed. To exclude any other causes that may explain such progressive liver failure, particularly liver infiltration from lymphoma, mini-laparoscopy guided liver biopsy was performed. Macroscopic and microscopic evaluation provided no evidence of recurrent lymphoma. Because of the extensive liver inflammation determined on histology, high-dose steroid therapy was started with 1.5 mg prednisolone/kg body weight. As shown in Figure 2B, in the following day transaminases decreased rapidly and viral load normalized. The finding of hepatomegaly in ultrasound imaging before glucocorticoid treatment (Figure 3A) was clearly reduced 2 mo after start of treatment (Figure 3B). After effective glucocorticoid therapy for 3 d the dose was reduced to 60 mg/d for 1 wk, then further reduced as described for patient N.1. The patient fully recovered within 2 mo (Figure 2B).

The patient N.1 showed evidence of fulminant acute HBV infection. According to case reports and in vivo data from HBV infected chimpanzees it seems that virus elimination in acute HBV infection is initiated by non-cytopathic antiviral effects, before adaptive immune responses, particularly CD8(+) cytotoxic T cells, are triggered[9,10]. However, in most of the cases the cytotoxic effect is self-limited and normalization of liver parameters in untreated patients usually takes 1-3 mo[11]. Aberrant and ongoing cytotoxic immune responses may lead to significant hepatic necro-inflammation, causing the reduction of hepatic synthetic functions, like in the described case 1. In this scenario of acute severe hepatitis B there is no well-established therapeutic strategy. Single case reports suggested a direct correlation between the initiation of entecavir therapy and improvement of liver parameters in patients with severe acute HBV[6,7]. However, we could not achieve a rapid beneficial effect upon entecavir administration, as transaminases and international normalized ratio increased dramatically within the first days of entecavir treatment, showing even more strongly affected coagulation than in the previously reported cases[6,7]. In this case of fulminant hepatits B, patient recovery is mainly determined by the rapid decrease of hepatic necro-inflammation that was provoked by an overwhelming immune response rather than by the virus itself. Therefore, the decrease of viral replication mediated by NUC therapy alone, which mainly causes reduction of circulating virions but not of viral antigens or amount of infected cells, may be not sufficient to promote a rapid suppression of liver inflammation within the short-term dramatic course of fulminant liver failure. On the other hand, additional glucocorticoid therapy was closely associated with a rapid decline of liver enzymes and international normalized ratio in our patient, indicating that prednisolone administration in combination with a potent antiviral like entecavir contributed to lessen the inflammation and hence immune-mediated liver damage. Moreover, HBsAg seroconversion was observed after 8 wk, thus indicating that combined entecavir and glucocorticoid therapy did not promote the establishment of chronic HBV infection.

Even after achieving negative HBV serum DNA levels and HBsAg seroconversion, the HBV minichromosome, which serves as template for viral transcription, can still be detected as covalently closed circular DNA in the hepatocyte nuclei[12]. Under immunosuppressive therapies like chemotherapies HBV replication can be reactivated, if pre-emptive antiviral therapy is missed or interrupted as reported here in cases 2A and 2B. The virus is then allowed to replicate without being controlled by adaptive immunity or antiviral agents. After cessation of chemotherapy, typically after rituximab therapy, the adaptive immune system restores. It is confronted with an increased intrahepatic viral load and reacts with an overwhelming cytotoxic response against infected hepatocytes. Rapid progression of liver inflammation and necrosis due to the killing of HBV-infected hepatocytes lead to fulminant liver failure. It is well established that acute liver failure due to HBV reactivation after chemotherapy has a poor prognosis[3]. According to the current guidelines, entecavir or tenofovir treatment was started in cases 2A and 2B. Despite moderate reduction of viremia within the first 2 wk, international normalized ratio and transaminases increased substantially. Similar to case 1, hepatic necro-inflammation was not directly affected by the relatively slow viral decrease, whereas T-cell inhibition by additional steroid therapy was accompanied by rapid improvement of clinical and liver parameters in the reported cases (Figure 2A and B). As steroid responsive elements of HBV have been reported to activate HBV replication directly[13], it might be expected that glucocorticoid therapy also increases HBV viremia. However, effects of steroid medication on Hepatitis B replication were well controlled by NUC therapy showing a clear decrease of viremia in all 3 cases after the beginning of steroid therapy (Figures 1 and 2). Despite the delayed antiviral effects induced by NUCs and their controversial role especially in acute HBV infection we thought that early initiation of entecavir/tenofovir therapy was necessary because of the use of glucocorticoids, since these may potentially augment viral replication, which in turn might even promote further cyotoxic immune responses against infected hepatocytes. Furthermore, no severe side effects of entecavir/tenofovir and glucocorticoid therapy were observed during hospitalisation and glucocorticoid therapy was accompanied by prophylactic medication with proton pump inhibitors and calcium/vitamin D to prevent steroid-induced gastric ulcers and osteoporosis, respectively. Patients were screened daily for clinical signs and biochemical parameters of infection during their stay in hospital while an antibiotic prophylaxis, f.e. for pneumocystis pneumonia, was avoided due to the short-term treatment with prednisolone.

It still remains unclear which therapeutic strategy is to be favoured in acute HBV related liver failure. There is limited and controversial evidence about the benefit of NUC therapy alone. While glucocorticoid therapy of overall liver failure has been rejected since the 1970s, recent Asian studies indicated a benefit of high-dose glucocorticoid therapy especially in early HBV related liver failure[14-16], but systematic studies about the efficacy of combined glucocorticoid and NUC therapy compared to standard therapy of HBV related liver failure are still missing. The cases reported here show evidence that glucocorticoid therapy combined with new NUCs should be re-evaluated in further clinical trials as a therapeutic strategy aiming to handle both HBV replication and the overwhelming adaptive immune responses that are triggered in HBV related acute liver failure.

Patient N.1: A 32-year-old woman presented with jaundice and pain in the right upper abdomen; and Patient N.2A/N.2B: A 66-year-old woman/57-year-old man with history of chemotherapy of lymphoma presented with jaundice.

Patient N.1: Fulminant acute hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection; Patient N.2A/B: HBV reactivation after rituximab chemotherapy with acute on chronic liver failure.

Patient N.1: Other viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, drug induced liver damage, mushroom poisoning, metabolic liver disease (M. Wilson, alpha-1-AT deficiency), acute fatty liver of pregnancy/ HELLP, Budd-Chiari-syndrome; and Patient N.2A/B: Malignant infiltration, drug induced liver damage (chemotherapy), other viral hepatitis, veno-occlusive disease.

Patient N.1: AST: 5104 IU/L; ALT: 4826 IU/L; total bilirubin: 7.2 mg/dL; international normalized ratio: 2.18; Patient N.2A: AST: 1006 IU/L; ALT: 1368 IU/L; total bilirubin: 15.8 mg/dL; international normalized ratio: 1.34; and Patient N.2B: AST: 1042 IU/L, ALT: 1933 IU/L, total bilirubin: 4.9 mg/dL; international normalized ratio: 1.17.

Ultrasound patient N.1: Diffuse damage of liver parenchyma; Ultrasound patient N.2A: Modest damage of liver parenchyma; and Ultrasound Patient N.2B: Hepatomegaly.

Patient N.2B: Mini-laparoscopy guided liver biopsy revealed highly active viral hepatitis (grade 4 according to the desmet scoring system) and mild fibrosis (stage 1 according to the desmet scoring system).

The patients were treated with 1 mg/d entecavir (patient N.1) or 245 mg/d tenofovir (patient N.2A and 2B) in combination with prednisolone (initial dose: 1-1,5 mg/kg body weight).

While there are limited and controversial data on the effectiveness of antiviral treatment in HBV-related liver failure, there is rising evidence that especially early and high-dose glucocorticoid therapy might be beneficial in this particular clinical situation.

Acute liver failure was defined by an international normalized ratio of greater than 1.5 and any degree of encephalopathy.

In the reported cases combined glucocorticoid and nucleotide analogue therapy was adopted not only in two cases of severe reactivations of chronic HBV infection, but also in a case of acute fulminant HBV infection. Rapid improvement of liver parameters and virological response was obtained in all three cases.

This is a case report on the favourable experience in three patients with HBV-related acute liver failure who were treated by combining high dose steroid therapy with standard antiviral treatment, which resulted in a rapid improvement of clinical and liver parameters. This case report is helpful for us to improve the treatment experience of glucocorticoid in HBV-related liver failure.

P- Reviewer: Gong ZJ, Sijens PE S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Shepard CW, Simard EP, Finelli L, Fiore AE, Bell BP. Hepatitis B virus infection: epidemiology and vaccination. Epidemiol Rev. 2006;28:112-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 645] [Cited by in RCA: 642] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | McMahon BJ. The natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2009;49:S45-S55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 557] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lalazar G, Rund D, Shouval D. Screening, prevention and treatment of viral hepatitis B reactivation in patients with haematological malignancies. Br J Haematol. 2007;136:699-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hsu C, Tsou HH, Lin SJ, Wang MC, Yao M, Hwang WL, Kao WY, Chiu CF, Lin SF, Lin J. Chemotherapy-induced hepatitis B reactivation in lymphoma patients with resolved HBV infection: a prospective study. Hepatology. 2014;59:2092-2100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pei SN, Chen CH, Lee CM, Wang MC, Ma MC, Hu TH, Kuo CY. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus following rituximab-based regimens: a serious complication in both HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative patients. Ann Hematol. 2010;89:255-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Girke J, Wedemeyer H, Wiegand J, Manns MP, Tillmann HL. [Acute hepatitis B: is antiviral therapy indicated? Two case reports]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;133:1178-1182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jochum C, Gieseler RK, Gawlista I, Fiedler A, Manka P, Saner FH, Roggendorf M, Gerken G, Canbay A. Hepatitis B-associated acute liver failure: immediate treatment with entecavir inhibits hepatitis B virus replication and potentially its sequelae. Digestion. 2009;80:235-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2323] [Cited by in RCA: 2401] [Article Influence: 184.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Guidotti LG, Rochford R, Chung J, Shapiro M, Purcell R, Chisari FV. Viral clearance without destruction of infected cells during acute HBV infection. Science. 1999;284:825-829. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Webster GJ, Reignat S, Maini MK, Whalley SA, Ogg GS, King A, Brown D, Amlot PL, Williams R, Vergani D. Incubation phase of acute hepatitis B in man: dynamic of cellular immune mechanisms. Hepatology. 2000;32:1117-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kumar M, Satapathy S, Monga R, Das K, Hissar S, Pande C, Sharma BC, Sarin SK. A randomized controlled trial of lamivudine to treat acute hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:97-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Levrero M, Pollicino T, Petersen J, Belloni L, Raimondo G, Dandri M. Control of cccDNA function in hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2009;51:581-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sagnelli E, Manzillo G, Maio G, Pasquale G, Felaco FM, Filippini P, Izzo CM, Piccinino F. Serum levels of hepatitis B surface and core antigens during immunosuppressive treatment of HBsAg-positive chronic active hepatitis. Lancet. 1980;2:395-397. [PubMed] |

| 14. | He B, Zhang Y, Lü MH, Cao YL, Fan YH, Deng JQ, Yang SM. Glucocorticoids can increase the survival rate of patients with severe viral hepatitis B: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:926-934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fujiwara K, Yasui S, Yonemitsu Y, Fukai K, Arai M, Imazeki F, Suzuki A, Suzuki H, Sadahiro T, Oda S. Efficacy of combination therapy of antiviral and immunosuppressive drugs for the treatment of severe acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:711-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yasui S, Fujiwara K, Nakamura M, Miyamura T, Yonemitsu Y, Mikata R, Arai M, Kanda T, Imazeki F, Oda S. Virological efficacy of combination therapy with corticosteroid and nucleoside analogue for severe acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22:92-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |