Published online Feb 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i5.1684

Peer-review started: August 18, 2014

First decision: August 27, 2014

Revised: September 16, 2014

Accepted: October 21, 2014

Article in press: October 21, 2014

Published online: February 7, 2015

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) represents a group of highly malignant tumors that give rise to early and widespread metastases at the time of diagnosis. The preferential metastatic sites are the brain, liver, adrenal glands, bone, and bone marrow. However, metastases of the gastrointestinal system, especially the stomach, are rare; most cases of stomach metastasis are asymptomatic and, as a result, are usually only discovered at autopsy. We report a case of gastric metastasis originating from SCLC. The patient was a 66-year-old man admitted to our hospital due to abdominal pain. He underwent gastroscopy, with the pathological report of the tissue biopsy proving it to be a small cell cancer. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD56, synaptophysin, and pan-cytokeratin. These results confirmed the diagnosis of gastric metastasis of a neuroendocrine small cell carcinoma from the lung.

Core tip: Small cell lung cancer metastases of the gastrointestinal system are rare; most cases of stomach metastasis are asymptomatic and as a result are usually only discovered at autopsy. We report a case of gastric metastasis originating from small cell lung cancer. The patient was a 66-year-old man admitted to our hospital due to abdominal pain and who underwent gastroscopy. The pathological report of the tissue biopsy proved it to be a small cell cancer, with immunohistochemistry being positive for CD56, synaptophysin, and pan-cytokeratin, thereby confirming the diagnosis of gastric metastasis of a neuroendocrine small cell carcinoma from the lung.

- Citation: Gao S, Hu XD, Wang SZ, Liu N, Zhao W, Yu QX, Hou WH, Yuan SH. Gastric metastasis from small cell lung cancer: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(5): 1684-1688

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i5/1684.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i5.1684

Lung cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide[1]. Neuroendocrine tumors occupy about 20% of lung cancers, with 15% of those being small cell lung cancer (SCLC)[2,3]. Over 90% of patients with SCLC are elderly and are either currently or formerly heavy smokers; this percentage has increased due to a longer duration and heavier intensity of smoking[4]. The most frequent symptoms of SCLC include coughing, dyspnea, wheezing, and hemoptysis caused by local intrapulmonary tumor growth, with symptoms caused by intrathoracic sources spreading to the chest wall, superior vena cava, or esophagus, while recurrent nerve pain, anorexia, fatigue, and neurological complaints are due to distant spread and paraneoplastic syndromes[5,6]. Approximately 50% of patients have widespread metastatic disease at the time of their initial diagnosis. The preferential metastatic sites are the brain, liver, adrenal glands, bone, and bone marrow[7]. Conversely, metastases of the gastrointestinal tract from SCLC are relatively infrequent; particularly so with regards to the stomach. Additionally, most cases of stomach metastasis are asymptomatic and, as a result, are usually only discovered at autopsy[8-10].

Here, we report on a case of a patient with a gastric metastasis originating from SCLC, which was confirmed by tissue biopsy and immunohistochemistry.

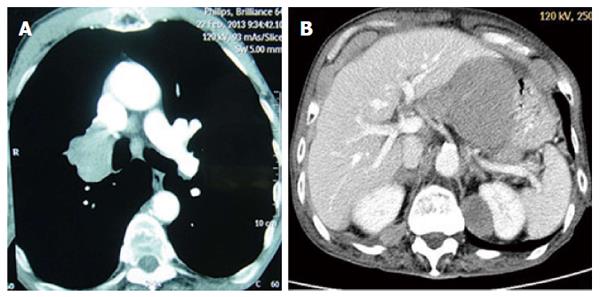

A 66-year-old man with a history of long-term heavy smoking was referred to our hospital due to a productive cough and chest tightness in February 2013. On admission, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest showed a lung mass approximately 5.0 cm × 4.0 cm in size at the right hilum (Figure 1A). Sputum cytology proved it to be small cell lung cancer (SCLC). No widespread metastatic disease was found by a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain, a CT scan of the chest and abdomen, or a full-body emission computed tomography (ECT) scan. The patient was therefore diagnosed with limited-stage SCLC. He was hospitalized and tolerated five successive courses of chemotherapy with etoposide (120 mg/m2 D1 + D2 + D3 - D1 = D21) and cisplatin (100 mg/m2 D1 - D1 = D21), followed by chest radiation (54 Gy/30 fractions/42 d). After this treatment, the patient received a CT scan of the chest, showing complete remission.

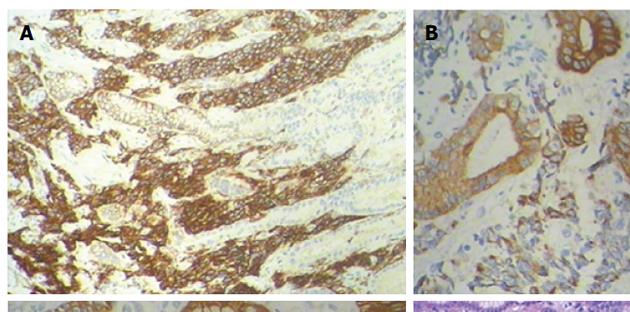

In April 2014, the patient returned to the hospital with epigastrium pain, a cough, expectoration, chest tightness, and suffocation. A CT scan of the epigastrium showed abnormal thickening in the stomach wall; between the liver, stomach, and retroperitoneum, lymph node tumefaction and integration were observed, with a maximum cross-section of approximately 8.6 cm × 6.6 cm (Figure 1B). Our patient underwent a gastroscopy that showed a large ulcer approximately 2.0 cm × 3.0 cm size in the posterior wall of the stomach. The pathological report of the tissue biopsy proved it to be a small cell cancer, with the immunohistochemistry results being positive for CD56, synaptophysin, and pan-cytokeratin (Figure 2). Based on the cytomorphology and immunocytochemistry, the diagnosis was gastric metastasis from SCLC.

Given the conservation of performance status and renal function, the patient received a doublet regimen of metastatic first-line chemotherapy based on etoposide (120 mg/m2 D1 + D2 + D3 - D1 = D21) and cisplatin (100 mg/m2 D1 - D1 = D21). After two cycles of the chemotherapy, a follow-up CT scan showed progression of the disease. The patient then received one cycle of second-line chemotherapy with irinotecan (60 mg/m2 D1 + D8 - D1 = D21). Following the chemotherapy regimen, and considering his poor condition, the patient was provided only with supportive care. He died three months after receiving the diagnosis of gastric metastasis from SCLC.

Lung cancer typically spreads from the lungs to the brain, liver, adrenal glands, bone, and bone marrow. In addition to the esophagus, metastasis to the gastrointestinal tract from lung cancer is not common and is often asymptomatic, with an incidence of approximately 0.3%-1.77%[11,12]. However, a much higher incidence has been noted during autopsies: gastrointestinal metastasis (stomach, small intestine, and large intestine) from lung cancer at autopsy has been reported to occur in 7.3%-12.2% of cases[8-10]. Upon searching the medical records of 470 patients with lung cancer confirmed by autopsy, Yoshimoto et al[13] identified 56 (11.9%) cases with gastrointestinal metastasis. Multiple metastases occurred in 6.2% (29), with metastasis to the stomach in 5.1% (24), small intestine in 8.1% (38), and large intestine in 4.5% (21). Of the 24 patients with stomach metastasis, the most common histological type of metastatic lung carcinoma to the stomach was adenocarcinoma, followed by squamous cell carcinoma and large cell carcinoma; only 3 cases were SCLC.

Indeed, gastric metastasis from lung cancer, especially SCLC, is very rare, with only sporadic published cases in the past several decades[14-23]. Symptoms of epigastralgia, chronic bleeding, anemia, and hematemesis were presented in those cases. More attention should therefore be paid to gastrointestinal metastatic signs (such as abdominal pain), especially when considering that it was the most frequent (80% of cases) symptom in symptomatic patients. Gastroscopy can be used to establish the diagnosis when necessary.

Lung cancer metastasis of the stomach is mostly caused by hematogenous metastasis. The direct invasion of cancer cells often occurs through the pulmonary vein, then through the left heart, with systemic blood transferred to organs and tissues throughout the body. Although transfer to the stomach is relatively rare, we cannot exclude the possibility of cancer cells in phlegm being swallowed and entering the stomach, thereby causing implantation metastasis.

Several studies have confirmed that PET scans can increase the accuracy of staging in patients with SCLC due to it being a highly metabolic disease[24,25]. A few researchers have also reported metastatic tumors of the gastrointestinal tract and the use of FDG-PET in gastrointestinal metastasis[26,27]. The function and potential value of FDG-PET scanning in gastric metastasis have been studied in recent years. Hayasaka et al[28] evaluated 308 patients who had undergone a whole-body FDG-PET scan for tumor detection, with four cases in which metastasis was found in the gastrointestinal tract being reviewed: one duodenal metastasis, one jejunal metastasis, and two stomach metastases from lung carcinoma. Thus, FDG-PET imaging provides the diagnosis of gastrointestinal metastasis with valuable information. Said observations suggest that imaging modality is valuable in the detection of metastatic tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, and therefore should be useful in preventing complications such as the intestinal obstruction and massive bleeding which are caused by metastatic tumors of the gastrointestinal tract[26].

Although PET/CT appears to improve staging accuracy in SCLC, pathologic confirmation is still required for PET/CT-detected lesions that result in upstaging. SCLC is defined as “a malignant epithelial tumour consisting of small cells with scant cytoplasm, ill-defined cell borders, finely granular nuclear chromatin, and absent or inconspicuous nucleoli”[29]. Immunohistochemical studies can confirm complicated cases. Testing for neuroendocrine markers, such as CD56, synaptophysin, and chromogranin, can be useful; indeed, less than ten percent of SCLC tumors are negative for all these markers. Meanwhile, among up to 90% of cases, SCLC is also positive for TTF-1. Epithelial markers, such as cytokeratins, which can help to distinguish SCLC from lymphomas and other small round tumors, are found in many SCLC tumors. In our case, the immunohistochemistry results were positive for synaptophysin, CD56, and pan-cytokeratin, which proved it to be a gastric metastasis of a neuroendocrine small cell carcinoma from the lung.

Chemotherapy leads to rapid responses, with occasionally striking improvement in symptoms and outcomes, as SCLC is very chemosensitive. The first-line treatment to extensive-stage SCLC is four to six cycles of etoposide combined with a platinum-based chemotherapy (cisplatin or carboplatin), which is better than other combined treatments according to two meta-analyses[30,31]. In six trials involving 1476 previously untreated Asian and Caucasian patients with extensive-stage SCLC, Jiang et al[32] found irinotecan and platinum combination regimens were associated with higher response rates and better overall survival than etoposide and cisplatin. Therefore, etoposide plus platinum is still regarded as the standard regimen for patients with SCLC, though irinotecan plus platinum has been added to guidelines as an option for patients with extensive-stage disease.

In conclusion, although gastric metastasis from lung cancer is very rare, we should pay more attention to gastrointestinal metastatic signs, with gastroscopy and FDG-PET imaging potentially providing valuable information for the diagnosis of gastrointestinal metastasis. Moreover, the use of immunocytochemistry may also help to confirm a suspected diagnosis. Etoposide plus platinum is still the standard regimen for patients with extensive-stage SCLC.

A 66-year-old man with a history of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) presented with epigastrium pain.

Gastric metastasis from small cell lung cancer.

Primary gastric cancer and primary gastric lymphoma.

A computed tomography scan of the epigastrium showed abnormal thickening in the stomach wall; between the liver, stomach, and retroperitoneal, lymph node tumefaction and integration were observed, with a maximum cross-section of approximately 8.6 cm × 6.6 cm.

Gastric metastasis originating from small cell lung cancer.

The patient was treated with two cycles of chemotherapy based on etoposide (120 mg/m2 D1 + D2 + D3 - D1 = D21) and cisplatin (100 mg/m2 D1 - D1 = D21), and one cycle of second-line chemotherapy with irinotecan (60 mg/m2 D1 + D8 - D1 = D21).

The preferential metastatic sites of SCLC are the brain, liver, adrenal glands, bone, and bone marrow. In contrast, metastases to the gastrointestinal system, especially the stomach, are rare.

Small cell lung cancer metastases to the gastrointestinal system are rare, and in most cases, stomach metastases are asymptomatic; as a result, they are usually only discovered at autopsy.

Although gastric metastasis from lung cancer is very rare, we should pay more attention to gastrointestinal metastatic signs; the use of immunocytochemistry, when available, may help to confirm a suspected diagnosis.

This article reports a rare case of gastric metastasis originating from small cell lung cancer, introduces the clinical characteristics of this tumor, and provides insight into therapeutic and diagnosis implications.

P- Reviewer: Li JF S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Rutherford A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in RCA: 25536] [Article Influence: 1824.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 2. | Öberg K, Hellman P, Ferolla P, Papotti M. Neuroendocrine bronchial and thymic tumors: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23 Suppl 7:vii120-vii123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Govindan R, Page N, Morgensztern D, Read W, Tierney R, Vlahiotis A, Spitznagel EL, Piccirillo J. Changing epidemiology of small-cell lung cancer in the United States over the last 30 years: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiologic, and end results database. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4539-4544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1197] [Cited by in RCA: 1395] [Article Influence: 73.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Devesa SS, Bray F, Vizcaino AP, Parkin DM. International lung cancer trends by histologic type: male: female differences diminishing and adenocarcinoma rates rising. Int J Cancer. 2005;117:294-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 524] [Cited by in RCA: 561] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Masters GA. Clinical presentation of small cell lung cancer. Principles and practice of lung cancer. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins 2010; 341-351. |

| 6. | Wilson LD, Detterbeck FC, Yahalom J. Clinical practice. Superior vena cava syndrome with malignant causes. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1862-1869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | van Meerbeeck JP, Fennell DA, De Ruysscher DK. Small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 2011;378:1741-1755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 662] [Cited by in RCA: 803] [Article Influence: 57.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hasegawa N, Yamasawa F, Kanazawa M, Kawashiro T, Kikuchi K, Kobayashi K, Ishihara T, Kuramochi S, Mukai M. [Gastric metastasis of primary lung cancer]. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1993;31:1390-1396. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Ryo H, Sakai H, Ikeda T, Hibino S, Goto I, Yoneda S, Noguchi Y. [Gastrointestinal metastasis from lung cancer]. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1996;34:968-972. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Capasso L, Iarrobino G, D’ Ambrosio R, Carfora E, Ventriglia R, Borsi E. [Surgical complications for gastric and small bowel metastases due to primary lung carcinoma]. Minerva Chir. 2004;59:397-403. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Rossi G, Marchioni A, Romagnani E, Bertolini F, Longo L, Cavazza A, Barbieri F. Primary lung cancer presenting with gastrointestinal tract involvement: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical features in a series of 18 consecutive cases. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:115-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yang CJ, Hwang JJ, Kang WY, Chong IW, Wang TH, Sheu CC, Tsai JR, Huang MS. Gastro-intestinal metastasis of primary lung carcinoma: clinical presentations and outcome. Lung Cancer. 2006;54:319-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yoshimoto A, Kasahara K, Kawashima A. Gastrointestinal metastases from primary lung cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:3157-3160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Maeda J, Miyake M, Tokita K, Iwahashi N, Nakano T, Tamura S, Hada T, Higashino K. Small cell lung cancer with extensive cutaneous and gastric metastases. Intern Med. 1992;31:1325-1328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim HS, Jang WI, Hong HS, Lee CI, Lee DK, Yong SJ, Shin KC, Shim YH. Metastatic involvement of the stomach secondary to lung carcinoma. J Korean Med Sci. 1993;8:24-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Baños Madrid R, Martínez Crespo JJ, Morán Sánchez S, Albaladejo Meroño A, Serrano Jiménez A, Mercader Martínez J. [Gastric metastasis from lung carcinoma]. An Med Interna. 2001;18:656-657. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Oh JC, Lee GS, Kim JS, Park Y, Lee SH, Kim A, Lee JM, Kim KS. [A case of gastric metastasis from small cell lung carcinoma]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2004;44:168-171. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Casella G, Di Bella C, Cambareri AR, Buda CA, Corti G, Magri F, Crippa S, Baldini V. Gastric metastasis by lung small cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4096-4097. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Koch B, Tannapfel A, Vieth M, Grün R. [Gastric metastasis from small cell lung cancer]. Pneumologie. 2009;63:585-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hung TI, Chu KE, Chou YH, Yang KC. Gastric metastasis of lung cancer mimicking an adrenal tumor. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2014;8:77-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Katsenos S, Archondakis S. Solitary gastric metastasis from primary lung adenocarcinoma: a rare site of extra-thoracic metastatic disease. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2013;4:E11-E15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nishikawa T, Hyoudou T, Kimura Y, Mori M, Kamikawa Y, Inoue F. [A suspicious case of metastasis to the stomach from primary lung cancer; report of a case]. Kyobu Geka. 2012;65:1093-1096. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Sileri P, D’Ugo S, Del Vecchio Blanco G, Lolli E, Franceschilli L, Formica V, Anemona L, De Luca C, Gaspari AL. Solitary metachronous gastric metastasis from pulmonary adenocarcinoma: Report of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3:385-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Podoloff DA, Ball DW, Ben-Josef E, Benson AB, Cohen SJ, Coleman RE, Delbeke D, Ho M, Ilson DH, Kalemkerian GP. NCCN task force: clinical utility of PET in a variety of tumor types. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7 Suppl 2:S1-26. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Azad A, Chionh F, Scott AM, Lee ST, Berlangieri SU, White S, Mitchell PL. High impact of 18F-FDG-PET on management and prognostic stratification of newly diagnosed small cell lung cancer. Mol Imaging Biol. 2010;12:443-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Alibazoglu H, Alibazoglu B, Ali A, La Monica G. False-negative FDG PET imaging in a patient with metastatic melanoma and ileal intussusception. Clin Nucl Med. 1999;24:129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tatlidil R, Mandelkern M. FDG-PET in the detection of gastrointestinal metastases in melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2001;11:297-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hayasaka K, Nihashi T, Matsuura T, Yagi T, Nakashima K, Kawabata Y, Ito K, Katoh T, Sakata K, Harada A. Metastasis of the gastrointestinal tract: FDG-PET imaging. Ann Nucl Med. 2007;21:361-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zakowski MF. Pathology of small cell carcinoma of the lung. Semin Oncol. 2003;30:3-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Pujol JL, Carestia L, Daurès JP. Is there a case for cisplatin in the treatment of small-cell lung cancer? A meta-analysis of randomized trials of a cisplatin-containing regimen versus a regimen without this alkylating agent. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:8-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mascaux C, Paesmans M, Berghmans T, Branle F, Lafitte JJ, Lemaitre F, Meert AP, Vermylen P, Sculier JP. A systematic review of the role of etoposide and cisplatin in the chemotherapy of small cell lung cancer with methodology assessment and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer. 2000;30:23-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jiang J, Liang X, Zhou X, Huang L, Huang R, Chu Z, Zhan Q. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing irinotecan/platinum with etoposide/platinum in patients with previously untreated extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:867-873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |