Published online Dec 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i47.13316

Peer-review started: June 8, 2015

First decision: August 26, 2015

Revised: August 31, 2015

Accepted: September 28, 2015

Article in press: September 30, 2015

Published online: December 21, 2015

Processing time: 192 Days and 21.6 Hours

AIM: To investigate the difference in long-term outcomes between gastric cancer patients with and without a primary symptom of overt bleeding (OB).

METHODS: Consecutive patients between January 1, 2007 and March 1, 2012 were identified retrospectively by reviewing a gastric cancer database at Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. A follow-up examination was performed on patients who underwent a radical gastrectomy. OB due to gastric cancer included hematemesis, melena or hematochezia, and gastric cancer was confirmed as the source of bleeding by endoscopy. Patients without OB were defined as cases with occult bleeding and those with other initial presentations, including epigastric pain, weakness, weight loss and obstruction. The 3-year overall survival (OS) rate, age, gender, AJCC T stage, AJCC N stage, overall AJCC stage, tumor size, histological type, macroscopic (Borrmann) type, lymphovascular invasion and R status were compared between patients with and without OB. Moreover, we carried out a subgroup analysis based on tumor location (upper, middle and lower).

RESULTS: We identified 939 patients. Of these, 695 (74.0%) were hospitalized for potential radical gastrectomy and another 244 received palliative resection, rerouting of the gastrointestinal tract, chemotherapy, radiotherapy or no treatment due to the presence of unresectable tumors. Notably, there was no significant difference in the percentage of OB patients between resectable cases and unresectable cases (20.3% vs 22.1%, P = 0.541). Follow-up examination was performed on 653 patients (94%) who underwent radical gastrectomy. We found no significant difference in 3-year OS rate (68.2% vs 61.2%, P = 0.143) or clinicopathological characteristics (P > 0.05) between these patients with and without OB. Subgroup analysis based on tumor location showed that the 3-year OS rate of upper gastric cancer was significantly higher in patients with OB (84.6%) than in those without OB (48.1%, P < 0.01) and that AJCC stages I-II (56.4% vs 35.1%, P = 0.017) and T1-T2 category tumors (30.8% vs 13%, P = 0.010) were more frequent in patients with OB than in those without OB. There was no significant difference in 3-year OS rate or clinicopathological characteristics between patients with and without OB (P > 0.05) for middle or lower gastric cancer.

CONCLUSION: Upper gastric cancer patients with OB exhibited tumors at less advanced pathological stages and had a better prognosis than upper gastric cancer patients without OB.

Core tip: Data regarding the clinicopathological characteristics and long-term outcomes of gastric cancer patients presenting with overt bleeding (OB) are extremely limited. Our result showed that the prognosis of gastric cancer patients with OB was no worse than the prognosis of those without OB. In fact, upper gastric cancer patients with OB exhibited tumors at less advanced pathological stages and had a better prognosis than upper gastric cancer patients without OB. This provided a new insight into the intrinsic nature of gastric cancer with OB.

- Citation: Wang L, Wang XA, Hao JQ, Zhang LN, Li ML, Wu XS, Weng H, Lv WJ, Zhang WJ, Chen L, Xiang HG, Lu JH, Liu YB, Dong P. Long-term outcomes after radical gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients with overt bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(47): 13316-13324

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i47/13316.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i47.13316

Gastrointestinal bleeding is classified as either overt bleeding (OB) or occult bleeding depending on the presence or absence of visible bleeding[1]. OB is one of the most frequent complications in patients with gastric cancer[2], as 1%-10% of hospitalized gastric cancer patients initially present with OB[3-7].

Numerous studies on gastric cancer bleeding have focused on hemostasis and rebleeding[2,4,5,7-9]. However, data regarding the clinicopathological characteristics and long-term outcomes of cases presenting with OB due to gastric cancer are extremely limited, and there are no reports comparing the clinical outcomes of patients with OB based on tumor location. The present study aimed to answer these questions, with a particular focus on OB in upper gastric cancer.

Consecutive gastric cancer patients that presented between January 1, 2007 and March 1, 2012 were identified retrospectively by reviewing a gastric cancer database at Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. The eligibility criteria for the study included: (1) histologically proven primary adenocarcinoma of the stomach; (2) no history of gastrectomy or other previous malignancies; (3) no prior chemotherapy or radiation therapy; and (4) involvement of only one portion of the stomach [the stomach is anatomically divided into three portions, upper (U), middle (M), and lower (L), according to the lines connecting the trisected points on the lesser and greater curvatures[10]]. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine.

Information collected from the database included the following: patient age and sex; the preoperative diagnosis; the surgical procedure performed; and the location, size, histological grade, macroscopic (Borrmann) type and stage of the primary tumor [according to the 7th edition of the AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer) cancer staging manual: stomach[11]]. The depth of invasion, the presence or absence of lymph node metastasis and lymphovascular invasion, and the type of resection-complete (R0) or incomplete resection (R1 or R2)-were also recorded. All of these criteria were compared between patients with and without OB.

OB due to gastric cancer included hematemesis, melena or hematochezia, and gastric cancer was confirmed as the source of bleeding by endoscopy. Patients without OB were defined as cases with occult bleeding and those with other initial presentations, including epigastric pain, weakness, weight loss and obstruction. A diagnosis of occult bleeding included a positive fecal occult blood test result and/or iron-deficiency anemia without evidence of visible fecal blood according to the patient or the physician[12-14].

Therapies for active bleeding included hemostatic drugs, endoscopic therapy and emergent embolization by interventional radiology. If hemostasis was not achieved, patients received emergency surgery both for bleeding and as a component of oncologic treatment. A careful pre- and intra-operative evaluation was performed on other patients. Those with unresectable tumors (poor performance status, distant metastasis and extensive abdominal metastasis) were treated via palliative resection, rerouting of the gastrointestinal tract, chemotherapy or radiotherapy. All patients with resectable tumors underwent radical gastrectomy and lymphadenectomy (D2+14v for advanced gastric cancer and D1 or D1+ for early gastric cancer) according to the guidelines of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association[15]. Histological evaluations were performed on all resected specimens. A final diagnosis of malignancy was established based on endoscopic biopsy or the histological assessment of the surgical specimens. Patients with an AJCC stages II-IV tumor received postoperative chemotherapy.

Patients who underwent radical gastrectomy were followed every 3 or 6 mo for 2 years and annually thereafter until death. The median follow-up duration for the entire cohort was 44 mo (range, 0-97 mo). A follow-up evaluation of all patients included in this study was completed by March 1, 2015. Ultrasonography, computed tomography, chest X-ray, and endoscopy were performed at each visit.

Consecutive variables were assessed by Student’s t-test, and results are given as mean ± SD. Mann-Whitney U tests were adopted when consecutive variables were not normal. Categorical variables were assessed by the Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Survival curves were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the use of the log-rank test, with stratification according to tumor location. Multivariate analysis by a Cox’s proportional hazards model was performed to identify independent prognostic factors of significance. All tests were two tailed. P values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. The analyses were performed with the use of IBM SPSS Statistics 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

During the study period, 939 consecutive gastric cancer patients were identified, including 195 (20.8%) with OB and 744 without OB. Of these, 695 (74.0%) were hospitalized for potential radical gastrectomy and another 244 received palliative resection, rerouting of the gastrointestinal tract, chemotherapy, radiotherapy or no treatment due to the presence of unresectable tumors accompanied by distant metastasis, extensive abdominal metastasis or poor performance status. Notably, there was no significant difference in the percentage of OB patients between resectable cases and unresectable cases (20.3% vs 22.1%, P = 0.541) (Table 1).

| OB | Non-OB | P value | |

| All | 0.541 | ||

| Resectable | 141 (20.3) | 554 (79.7) | |

| Unresectable | 54 (22.1) | 190 (77.9) | |

| Upper | 0.136 | ||

| Resectable | 41 (22.9) | 138 (77.1) | |

| Unresectable | 14 (15.2) | 78 (84.8) | |

| Middle | 0.887 | ||

| Resectable | 17 (24.3) | 53 (75.7) | |

| Unresectable | 9 (23.1) | 30 (76.9) | |

| Lower | 0.038a | ||

| Resectable | 83 (18.6) | 363 (81.4) | |

| Unresectable | 31 (27.4) | 82 (72.6) |

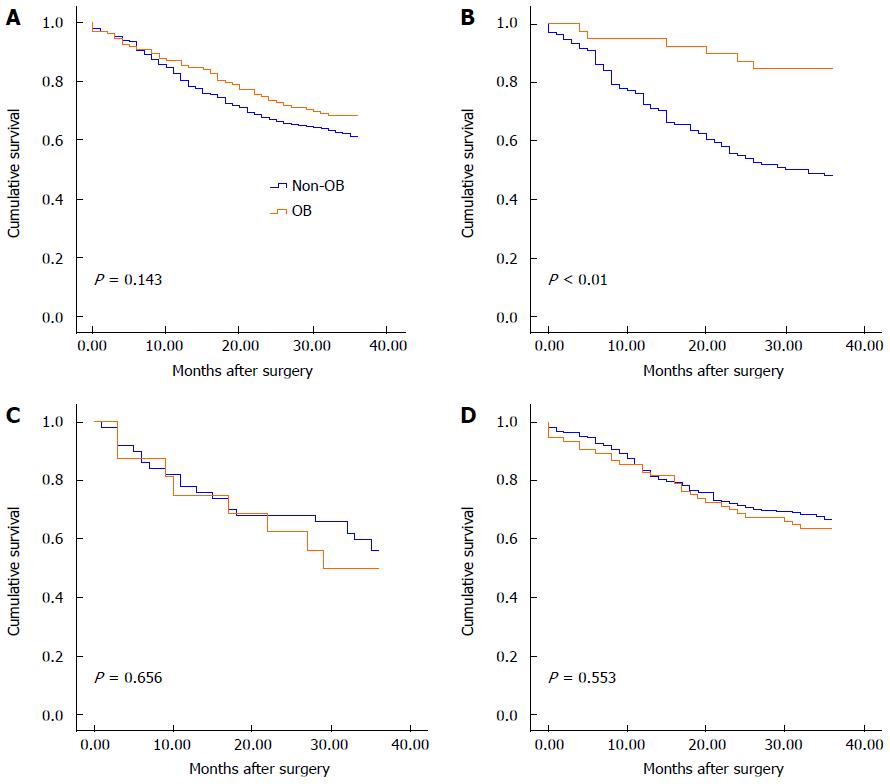

A follow-up examination was performed on 653 (94.0%) of the 695 patients who underwent a radical gastrectomy. The patients who underwent follow-up were aged 63.0 ± 12.0 years (range, 16-93 years). The male-to-female ratio among the 653 enrolled patients was 2.05 (439 males and 214 females). Of these patients, 132 (20.2%) were hospitalized with a primary symptom of OB. Additionally, 128 patients who achieved hemostasis underwent elective surgery, whereas 4 patients who failed to achieve hemostasis underwent emergency surgery. The characteristics of the 132 patients with OB and the 521 patients without OB were comparable (Table 2). There was no significant difference in the 3-year overall survival rate between patients with OB (68.2%, 319/521) and those without OB (61.2%, 90/132, P = 0.143) (Figure 1A).

| All | Upper gastric cancer | |||||

| Non-OB | OB | P value | Non-OB | OB | P value | |

| Gender1 | 0.718 | 0.996 | ||||

| Male | 352 (67.6) | 87 (65.9) | 94 (71.8) | 28 (71.8) | ||

| Female | 169 (32.4) | 45 (34.1) | 37 (28.2) | 11 (28.2) | ||

| Age2 | 63.2 ± 11.6 | 62.2 ± 13.4 | 0.497 | 64.8 ± 10.6 | 62 ± 12.8 | 0.276 |

| AJCC stage1 | 0.081 | 0.017a | ||||

| I-II | 240 (46.1) | 72 (54.5) | 46 (35.1) | 22 (56.4) | ||

| III-IV | 281 (53.9) | 60 (45.5) | 85 (64.9) | 17 (43.6) | ||

| T category1 | 0.201 | 0.010a | ||||

| T1-T2 | 163 (31.3) | 49 (37.1) | 17 (13) | 12 (30.8) | ||

| T3-T4 | 358 (68.7) | 83 (62.9) | 114 (87) | 27 (69.2) | ||

| Involved lymph nodes2 | 5.4 ± 7.8 | 4.7 ± 6.5 | 0.523 | 4.9 ± 5.9 | 4.2 ± 6.0 | 0.248 |

| N category1 | 0.793 | 0.311 | ||||

| N0 | 187 (35.9) | 49 (37.1) | 36 (27.5) | 14 (35.9) | ||

| N1-N3 | 334 (64.1) | 83 (62.9) | 95 (72.5) | 25 (64.1) | ||

| Macroscopic (Borrmann) type1 | 0.357 | 0.036a | ||||

| EGC | 90 (17.5) | 19 (14.4) | 8 (6.1) | 4 (10.3) | ||

| I | 30 (5.8) | 14 (10.6) | 8 (6.1) | 8 (20.5) | ||

| II | 325 (62.4) | 81 (61.4) | 89 (67.9) | 23 (59) | ||

| III | 23 (4.4) | 5 (3.8) | 9 (6.9) | 0 (0) | ||

| IV | 52 (10) | 13 (9.8) | 17 (13) | 4 (10.3) | ||

| Histological grade1 | 0.448 | 0.770 | ||||

| G1-G2 | 176 (33.8) | 40 (30.3) | 47 (35.9) | 13 (33.3) | ||

| G3-G4 | 345 (66.2) | 92 (69.7) | 84 (64.1) | 26 (66.7) | ||

| Size (cm)2 | 4.7 ± 2.9 | 4.1 ± 2.1 | 0.083 | 5.4 ± 3.0 | 4.1 ± 2.0 | 0.018a |

| R status1 | 0.729 | 0.114 | ||||

| R0 | 508 (97.5) | 130 (98.5) | 123 (93.9) | 39 (100) | ||

| R1 | 13 (2.5) | 2 (1.5) | 8 (6.1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Lymphovascular invasion1 | 0.785 | 0.484 | ||||

| Positive | 437 (83.9) | 112 (84.8) | 108 (82.4) | 34 (87.2) | ||

| Negative | 84 (16.1) | 20 (15.2) | 23 (17.6) | 5 (12.8) | ||

Two hundred and seventy-one consecutive upper gastric cancer patients were identified. Of these, 179 (66.1%) underwent radical gastrectomy. There was no significant difference in the percentage of patients with OB between resectable cases and unresectable cases (22.9% vs 15.2%, P = 0.136) (Table 1). A follow-up examination was performed on 170 (95.0%) out of the 179 patients who underwent radical gastrectomy, including 39 (22.9%) with OB and 131 (77.1%) without OB. Of the 39 tumors in OB cases, 33 (82.1%) were found in the cardia and the lesser curvature and 6 (15.4%) were located in the fundus and the greater curvature of the stomach. The clinicopathological characteristics are presented in Table 2. Characteristics including gender, age, AJCC N stage, the number of involved lymph nodes, histological grade, tumor size, R status and lymphovascular invasion status (P > 0.05) were similar between patients with and without OB. Early gastric cancer and Borrmann type I tumors were observed more frequently in patients with OB. Comparing the clinicopathological characteristics according to invasion depth and AJCC stage, the percentage of patients with AJCC T1-T2 category tumors was significantly higher among patients with OB than among those without OB (30.8% vs 13%, P = 0.010), and the proportion of patients with AJCC stages I-II tumors was significantly higher among patients with OB than among those without OB (56.4% vs 35.1%, P = 0.017). Moreover, patients presenting with OB had smaller primary tumors than those without OB (4.1 ± 2.0 cm vs 5.4 ± 3.0 cm, P = 0.018). The 3-year overall survival rate was significantly higher in patients with OB (84.6%) than in those without OB (48.1%, P < 0.01; Figure 1B).

Table 3 summarizes the results of univariate and multivariate analyses. The factors considered in the univariate and multivariate models of overall survival included age, sex, AJCC T stage, AJCC N stage, overall AJCC stage, tumor size, histological type, macroscopic (Borrmann) type, lymphovascular invasion, R status and OB. Based on multivariate survival analysis, only overall AJCC stage (HR = 1.638, 95%CI: 1.366-1.966, P < 0.001), tumor size (HR = 1.090, 95%CI: 1.012-1.174, P = 0.023) and OB (vs non-OB) (HR = 0.346, 95%CI: 0.148-0.808, P = 0.014) were determined to be independent prognostic factors.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age1 | ||||

| Gender (vs male)2 | 0.056 | |||

| OB vs non-OB2 | < 0.001b | 0.346 | 0.148-0.808 | 0.014a |

| AJCC stage3 | < 0.001b | 1.638 | 1.366-1.966 | < 0.001b |

| AJCC T category3 | < 0.001b | |||

| AJCC N category3 | < 0.001b | |||

| Macroscopic (Borrmann) type2 (vs type I) | 0.003b | |||

| II | ||||

| III | ||||

| IV | ||||

| Histological type3 | 0.069 | |||

| Size1 | 1.090 | 1.012-1.174 | 0.023a | |

| R status2 (vs R0) | 0.008b | |||

| R1 | ||||

| Lymphovascular invasion2 | 0.001b | |||

| (vs negative) | ||||

| Positive | ||||

A total of 109 consecutive middle gastric cancer patients were included. Of these, 70 (64.2%) underwent radical gastrectomy. There was no difference in the percentage of patients with OB between resectable cases and unresectable cases (24.3% vs 23.1%, P = 0.887) (Table 1). A follow-up examination was performed on 66 (94.3%) of the radical gastrectomy patients. Of these, 16 (24.2%) were hospitalized with an initial manifestation of OB. The characteristics of the patients with or without OB were comparable (Table 4). No significant difference in age, sex, overall AJCC stage, AJCC T stage, AJCC N stage, the number of involved lymph nodes, macroscopic (Borrmann) type, histological grade, tumor size, R status or lymphovascular invasion status (P > 0.05) was observed between patients with and without OB. The 3-year overall survival rates were also similar between these groups (50% vs 56%, P = 0.656; Figure 1C). Multivariate survival analysis was not performed on the middle gastric cancer patients because of the small sample size.

| Middle gastric cancer | Lower gastric cancer | |||||

| Non-OB | OB | P value | Non-OB | OB | P value | |

| Gender1 | 0.902 | 0.684 | ||||

| Male | 29 (58) | 9 (56.3) | 229 (67.4) | 50 (64.9) | ||

| Female | 21 (42) | 7 (43.8) | 111 (32.6) | 27 (35.1) | ||

| Age2 | 62.3 ± 11.2 | 61.3 ± 14.8 | 0.616 | 62.8 ± 11.9 | 62.6 ± 13.6 | 1.000 |

| AJCC stage1 | 0.319 | 0.659 | ||||

| I-II | 18 (36.0) | 8 (50.0) | 176 (51.8) | 42 (54.5) | ||

| III-IV | 32 (64.0) | 8 (50.0) | 164 (48.2) | 35 (45.5) | ||

| T category1 | 0.291 | 0.891 | ||||

| T1-T2 | 12 (24) | 6 (37.5) | 134 (39.4) | 31 (40.3) | ||

| T3-T4 | 38 (76) | 10 (62.5) | 206 (60.6) | 46 (59.7) | ||

| Involved lymph nodes2 | 8.5 ± 10.6 | 7.1 ± 9.0 | 0.432 | 5.1 ± 7.9 | 4.5 ± 6.2 | 0.844 |

| N category1 | 0.104 | 0.396 | ||||

| N0 | 14 (28.0) | 8 (50) | 137 (40.3) | 27 (35.1) | ||

| N1-N3 | 36 (72.0) | 8 (50) | 203 (59.7) | 50 (64.9) | ||

| Macroscopic (Borrmann) type1 | 0.577 | 0.742 | ||||

| EGC | 7 (14.0) | 3 (18.8) | 76 (22.4) | 12 (15.6) | ||

| I | 4 (8.0) | 2 (12.5) | 18 (5.3) | 4 (5.2) | ||

| II | 29 (58.0) | 7 (43.8) | 207 (60.9) | 51 (66.2) | ||

| III | 2 (4.0) | 2 (12.5) | 12 (3.5) | 3 (3.9) | ||

| IV | 8 (16.0) | 2 (12.5) | 27 (7.9) | 7 (9.1) | ||

| Histological grade1 | 0.554 | 0.282 | ||||

| G1-G2 | 10 (20) | 5 (31.3) | 119 (35.0) | 22 (28.6) | ||

| G3-G4 | 40 (80) | 11 (68.8) | 221 (65) | 55 (71.4) | ||

| Size (cm)2 | 5.0 ± 3.0 | 4.0 ± 2.5 | 0.246 | 4.4 ± 2.8 | 4.1 ± 2.1 | 0.745 |

| R status1 | 1.000 | 0.559 | ||||

| R0 | 48 (96.0) | 15 (93.8) | 337 (99.1) | 76 (98.7) | ||

| R1 + R2 | 2 (4.0) | 1 (6.3) | 3 (0.9) | 1 (1.3) | ||

| Lymphovascular invasion1 | 0.266 | 0.445 | ||||

| Positive | 39 (78.0) | 15 (93.8) | 290 (85.3) | 63 (81.8) | ||

| Negative | 11 (22.0) | 1 (6.3) | 50 (14.3) | 14 (18.2) | ||

A total of 559 consecutive lower gastric cancer patients were observed. Of these, 446 (79.9%) underwent radical gastrectomy. The percentage of patients with OB was significantly different between resectable and unresectable cases (18.6% vs 27.6%, P = 0.038) (Table 1). A follow-up examination was performed on 417 (93.5%) out of the 446 patients who underwent radical gastrectomy, including 77 (18.5%) patients with OB and 340 (81.5%) patients without OB. The characteristics of the patients with and without OB were comparable (Table 4). Similar 3-year overall survival rates were observed between these groups (63.6% vs 67.1%, P = 0.553; Figure 1D). The factors used in the univariate and multivariate models for lower gastric cancer patients were the same that were used for upper gastric cancer patients. The results of univariate and multivariate analyses of the clinical and pathological characteristics are presented in Table 5. Based on multivariate survival analysis, only the overall AJCC stage (HR = 1.690, 95%CI: 1.508-1.894, P < 0.001), lymphovascular invasion status (positive vs negative, HR = 1.687, 95%CI: 1.160-2.455, P = 0.006) and age (HR = 1.023, 95%CI: 1.008-1.037, P = 0.002) were determined to be independent prognostic factors.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age1 | 1.023 | 1.008-1.037 | 0.002 | |

| Gender (vs male)2 | 0.930 | |||

| OB vs non-OB2 | 0.553 | |||

| AJCC stage3 | < 0.001b | 1.690 | 1.508-1.894 | < 0.001 |

| AJCC T category3 | < 0.001b | |||

| AJCC N category3 | < 0.001bb | |||

| Macroscopic (Borrmann) type2 (vs type I) | < 0.001b | |||

| II | ||||

| III | ||||

| IV | ||||

| Histological type3 | 0.001b | |||

| Size1 | ||||

| R status2 (vs R0) | 0.003b | |||

| R1 | ||||

| Lymphovascular invasion2 (vs negative) | < 0.001b | 1.687 | 1.160-2.455 | 0.006 |

| Positive | ||||

OB in patients with gastric cancer is a rare but serious condition with potentially dangerous effects. Although numerous studies have been conducted on the risk factors associated with gastric cancer bleeding and rebleeding, data regarding long-term outcomes following surgery and the pathological characteristics of gastric cancer patients with OB are extremely limited. The results of the current study provide information for clinical physicians to use when evaluating gastric cancer patients with OB. These findings also provide the following new perspectives relevant to our understanding of this group of patients: gastric cancer with OB is not synonymous with advanced gastric cancer, and its prognosis is no worse than the prognosis for gastric cancer without OB. In fact, patients with proximal gastric cancer with OB exhibit less advanced pathological stages and a better prognosis than patients with proximal gastric cancer without OB.

To investigate why the 3-year overall survival rate following surgery was significantly higher for upper gastric cancer patients presenting with OB than without OB, we compared clinicopathological characteristics between these two subgroups of upper gastric cancer patients. Our results revealed that compared to proximal gastric cancer patients without OB, those with OB exhibited not only less advanced tumors with respect to both overall AJCC stage and AJCC T stage but also smaller tumors. Further multivariate survival analysis demonstrated that the overall AJCC stage, tumor size and OB were independent factors affecting prognosis. An increment of one stage in the overall AJCC classification was associated with a 1.638-fold increased risk of death within 3 years of surgery. This result may explain why the former type of cancer exhibits a more positive prognosis. Fox et al[16] demonstrated that 62% of gastric cancer patients with bleeding were classified as overall AJCC stages I-II. Similarly, Kodama[17] and colleagues and Moreno-Otero et al[6] found that 72.2% of these patients exhibited early stage tumors and an intraluminal growth pattern with irregularly distributed erosions or shallow, but not deep, ulcerations. These previous results support the findings of the current study. Gertsch et al[18] compared the prognosis of gastric cancer patients with bleeding and serosal invasion with the prognosis of gastric cancer patients without complications, but found no statistically significant difference in clinicopathological characteristics or prognosis between the two groups. The following two considerations could explain why the results of Gertsch et al[18] were not consistent with the findings of the current study. On one hand, Gertsch et al[18] did not perform a stratified analysis that accounted for the differences in the locations of gastric cancer. On the other hand, the two studies assessed different subject populations: in particular, Gertsch et al[18] examined gastric carcinoma patients with serosal invasion, whereas we examined all gastric cancer patients at tumor stages T1-T4b.

Bleeding occurs as a result of gastric cancer for many reasons, including an increase in the size of the tumor body, insufficient blood supply to the central portion of the tumor, the softening, necrosis, and ulceration of tumor tissues, bleeding from the surface of the tumor ulcer, and the rupture of small and medium blood vessels[6]. An interesting phenomenon discovered in this study was that in cases of upper gastric cancer, tumors accompanied by OB tended to be classified as an earlier pathological stage than tumors without OB; however, lower gastric adenocarcinomas did not follow this trend. Why did gastric adenocarcinomas with OB at different locations exhibit such different pathological presentations? Koh et al[2] examined the effects of different hemostasis treatment methods on bleeding resulting from gastric cancer and found that when transarterial embolization was performed after endoscopic hemostasis had failed, the left gastric artery was the predominant problematic artery. These results suggested that it would be challenging to stop gastric cancer bleeding from the left gastric artery. The current study also found that in 82.1% of upper gastric cancer patients with OB, the tumor was located in the cardia and the lesser curvature, for which the left gastric artery is the main feeding artery. Based on the combination of the results of the present study and the findings of Koh et al[2], we propose the following hypothesis. The left gastric artery and its branches are adjacent to the celiac artery and have high pressure and rich blood flow. Therefore, tumors in the cardia and the lesser curvature grow rapidly and readily display invasion and necrosis. When tumor tissue infiltration destroys branches of the left gastric artery, any resulting bleeding may be resistant to self-coagulation because these branches have high vascular pressure; thus, OB can easily occur in these cases. Therefore, OB provides an opportunity for the early diagnosis and treatment of upper gastric cancer patients. Lower gastric adenocarcinomas typically arise at the gastric antrum. The blood supply to this location is primarily provided by the right gastric artery and the right gastroepiploic artery, which originate from the proper hepatic artery and the gastroduodenal artery, respectively. Both of these arteries are far from the celiac artery and have relatively low pressure. When tumor tissues invade the branches of these arteries, the resulting bleeding can relatively rapidly coagulate, and the subsequent recurrence and non-OB cause fibrosis and thrombosis near the blood vessels. Thus, OB does not readily occur in these cases. This hypothesis requires additional validation by future studies. Another process could cause OB resulting from a proximal gastric adenocarcinoma. The cardia is narrower than other parts of the stomach, and tumor tissue infiltration increases vascular fragility at this location. When food passes the cardia, it is in a rough, undigested state. Therefore, mechanical stimuli can easily cause the rupture of blood vessels at this site.

Bleeding resulting from gastric cancer is closely associated with the vascular composition of the tumor. In 1971, Folkman[19] proposed that tumor growth is dependent on angiogenesis. Furthermore, he suggested that tumor cells and blood vessels constitute a highly integrated environment. Angiogenesis plays an important role in the process of cancer development[20,21]. High intratumor microvessel density correlates with high AJCC stage and lymph node metastasis. Intratumor microvessel density was found to have independent prognostic significance to cancer[22], including gastric cancer[23], compared to traditional prognostic markers based on multivariate analysis. Studies in Japan and China[24] showed that the vascular composition of gastric cancer can be categorized into hypovascular and hypervascular tumors, corresponding to Borrmann types II-III and Borrmann types I and IV gastric adenocarcinomas, respectively. In the current study, among upper gastric cancer cases, OB was observed more frequently in cases of early gastric cancer and Borrmann type I tumors. There was no difference in the percentage of Borrmann types II-IV tumors between upper gastric cancer patients with and without OB. Is the microvessel density or the Borrmann type of gastric adenocarcinomas associated with hemorrhaging from these tumors? Additional large-scale studies are warranted to precisely determine the impact of intratumor microvessel density on hemorrhaging from gastric cancer.

To determine whether selection bias may have influenced the conclusions of the current study, we investigated all patients receiving all types of therapies from our database and found that the rate of OB was similar between resectable and unresectable tumors. Therefore, selection bias was not possible for the whole patient group and upper gastric cancer cohort. But in the lower gastric cancer cases, the percentage of patients with OB in patients who underwent radical gastrectomy was lower than the percentage of patients with OB in patients who did not undergo radical gastrectomy. Including patients who did not undergo radical gastrectomy, the overall 3-year survival rate may be lower in patients with OB than in patients without OB.

Cases of proximal gastric cancer, particularly cancer of the gastric cardia, only manifest as significant symptoms such as epigastric pain, weakness, weight loss and obstruction after the tumor has deeply infiltrated the gastric tissue. Therefore, most patients already have mid- to late-stage cancer by the time that they seek treatment to relieve the symptoms of eating difficulties and abdominal pain. As a result, these patients exhibit a poor prognosis. A subset of patients without OB have occult bleeding; however, this type of bleeding is generally not discovered in a timely fashion, resulting in the delay of disease treatment. Because there is currently no reliable tumor screening system in China, early diagnoses are difficult to obtain. Thus, OB provides an opportunity to diagnose proximal gastric cancer at an earlier pathological stage, thereby significantly improving patient prognosis.

Gastrointestinal bleeding is classified as either overt bleeding (OB) or occult bleeding depending on the presence or absence of visible bleeding. OB is one of the most frequent complications in patients with gastric cancer, as 1%-10% of hospitalized gastric cancer patients initially present with OB.

Numerous studies on gastric cancer bleeding have focused on hemostasis and rebleeding. However, data regarding the clinicopathological characteristics and long-term outcomes of cases presenting with OB due to gastric cancer are extremely limited, and there are no reports comparing the clinical outcomes of patients with OB based on tumor location. The present study aimed to answer these questions and provide new perspectives relevant to our understanding of this group of patients.

The results of the current study provide information for clinical physicians to use when evaluating gastric cancer patients with OB. These findings also provide the following new perspectives relevant to our understanding of this group of patients: gastric cancer with OB is not synonymous with advanced gastric cancer, and its prognosis is no worse than the prognosis for gastric cancer without OB. In fact, patients with proximal gastric cancer with OB exhibit less advanced pathological stages and a better prognosis than patients with proximal gastric cancer without OB.

OB provides an opportunity to diagnose proximal gastric cancer at an earlier pathological stage, thereby significantly improving patient prognosis.

The paper is an interesting study which provided a new perspective relevant to our understanding of gastric cancer patients with overt bleeding: overt bleeding provides an opportunity to diagnose proximal gastric cancer at an earlier pathological stage, thereby significantly improving patient prognosis. It is necessary to conduct a prospective clinical study to confirm the result and to find out the intrinsic difference between gastric cancer with overt bleeding and gastric cancer without overt bleeding.

P- Reviewer: Berkane S, Cottam DR S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Leung WK, Ho SS, Suen BY, Lai LH, Yu S, Ng EK, Ng SS, Chiu PW, Sung JJ, Chan FK. Capsule endoscopy or angiography in patients with acute overt obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: a prospective randomized study with long-term follow-up. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1370-1376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Koh KH, Kim K, Kwon DH, Chung BS, Sohn JY, Ahn DS, Jeon BJ, Kim SH, Kim IH, Kim SW. The successful endoscopic hemostasis factors in bleeding from advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:397-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Webb WA, McDaniel L, Johnson RC, Haynes CD. Endoscopic evaluation of 125 cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Surg. 1981;193:624-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Savides TJ, Jensen DM, Cohen J, Randall GM, Kovacs TO, Pelayo E, Cheng S, Jensen ME, Hsieh HY. Severe upper gastrointestinal tumor bleeding: endoscopic findings, treatment, and outcome. Endoscopy. 1996;28:244-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Loftus EV, Alexander GL, Ahlquist DA, Balm RK. Endoscopic treatment of major bleeding from advanced gastroduodenal malignant lesions. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:736-740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Moreno-Otero R, Rodriguez S, Carbó J, Mearin F, Pajares JM. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding as primary symptom of gastric carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 1987;36:130-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sheibani S, Kim JJ, Chen B, Park S, Saberi B, Keyashian K, Buxbaum J, Laine L. Natural history of acute upper GI bleeding due to tumours: short-term success and long-term recurrence with or without endoscopic therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:144-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pereira J, Phan T. Management of bleeding in patients with advanced cancer. Oncologist. 2004;9:561-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kasakura Y, Ajani JA, Mochizuki F, Morishita Y, Fujii M, Takayama T. Outcomes after emergency surgery for gastric perforation or severe bleeding in patients with gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2002;80:181-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2872] [Article Influence: 205.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Washington K. 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: stomach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3077-3079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 702] [Cited by in RCA: 814] [Article Influence: 58.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zuckerman GR, Prakash C, Askin MP, Lewis BS. AGA technical review on the evaluation and management of occult and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:201-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 339] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rockey DC. Occult and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: causes and clinical management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:265-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Spraycar M. Stedman’s medical dictionary. 26th ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins 1995; . |

| 15. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1723] [Cited by in RCA: 1896] [Article Influence: 135.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fox JG, Hunt PS. Management of acute bleeding gastric malignancy. Aust N Z J Surg. 1993;63:462-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kodama Y, Inokuchi K, Soejima K, Matsusaka T, Okamura T. Growth patterns and prognosis in early gastric carcinoma. Superficially spreading and penetrating growth types. Cancer. 1983;51:320-326. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Gertsch P, Chow LW, Yuen ST, Chau KY, Lauder IJ. Long-term survival after gastrectomy for advanced bleeding or perforated gastric carcinoma. Eur J Surg. 1996;162:723-727. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1182-1186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5115] [Cited by in RCA: 5899] [Article Influence: 109.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Kolev Y, Uetake H, Iida S, Ishikawa T, Kawano T, Sugihara K. Prognostic significance of VEGF expression in correlation with COX-2, microvessel density, and clinicopathological characteristics in human gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2738-2747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhang X, Zheng Z, Shin YK, Kim KY, Rha SY, Noh SH, Chung HC, Jeung HC. Angiogenic factor thymidine phosphorylase associates with angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in the intestinal-type gastric cancer. Pathology. 2014;46:316-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Weidner N. Intratumor microvessel density as a prognostic factor in cancer. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:9-19. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Isozaki H, Fujii K, Nomura E, Mabuchi H, Hara H, Sako S, Nishiguchi K, Ohtani M, Tenjo T, Nohara T. Prognostic value of tumor cell proliferation and intratumor microvessel density in advanced gastric cancer treated with curative surgery. Int J Oncol. 1998;13:255-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chen JQ, Zhang WF, Shan JX. Some characteristics of the stomach carcinoma haemorrhea and their clinical significance. Zhongguo Yike Daxue Xuebao. 1985;19:19-22. |