Published online Jan 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i4.1344

Peer-review started: June 12, 2014

First decision: July 9, 2014

Revised: July 22, 2014

Accepted: September 12, 2014

Article in press: September 16, 2014

Published online: January 28, 2015

Processing time: 229 Days and 19.7 Hours

We report an extremely rare case of pulmonary lipiodol embolism with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). A 77-year-old man who was diagnosed with a huge HCC was admitted for TACE. Immediately after the procedure, this patient experienced severe dyspnea. We suspected that his symptoms were associated with a pulmonary lipiodol embolism after TACE, and we began intensive treatment. However, his condition did not improve, and he died on the following day. A subsequent autopsy revealed that the cause of death was ARDS due to pulmonary lipiodol embolism. No cases have been previously reported for which an autopsy was performed to explain the most probable mechanism of pulmonary lipiodol embolism; thus, ours is the first report for such a rare case.

Core tip: Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) has become the first treatment choice for patients with non-surgical hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Common complications associated with TACE have been reported, which include acute hepatic failure, liver abscess, intrahepatic biloma, hepatic infarction, hepatic artery occlusion, gallbladder infarction, acute renal failure, and/or gastrointestinal mucosal ulceration. However, fatal complications are rare. Although a few cases with pulmonary lipiodol embolism were previously reported, to our knowledge there have been no pathological autopsy reports. Here we present a pathological autopsy report for a patient with a huge HCC who died due to pulmonary lipiodol embolism after TACE.

- Citation: Hatamaru K, Azuma S, Akamatsu T, Seta T, Urai S, Uenoyama Y, Yamashita Y, Ono K. Pulmonary embolism after arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: An autopsy case report. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(4): 1344-1348

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i4/1344.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i4.1344

Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) has become the first treatment choice for patients with non-surgical hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Common complications associated with TACE have been reported, which include acute hepatic failure, liver abscess, intrahepatic biloma, hepatic infarction, hepatic artery occlusion, gallbladder infarction, acute renal failure, and/or gastrointestinal mucosal ulceration. However, fatal complications are rare.

Although a few cases with pulmonary lipiodol embolism were previously reported, to our knowledge there have been no pathological autopsy reports. Here we present a pathological autopsy report for a patient with a huge HCC who died due to pulmonary lipiodol embolism after TACE.

A 77-year-old man with a huge HCC was admitted to our hospital in April 2013 for the purpose of undergoing TACE. Since May 2011, he had been treated with chemotherapy for advanced lung cancer, although this was not sufficiently effective. Thus, after his admission, the treatment plan for his lung cancer was palliative therapy. Although contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) had shown a liver mass in November 2011, we thought this to be a metastatic tumor from his lung cancer.

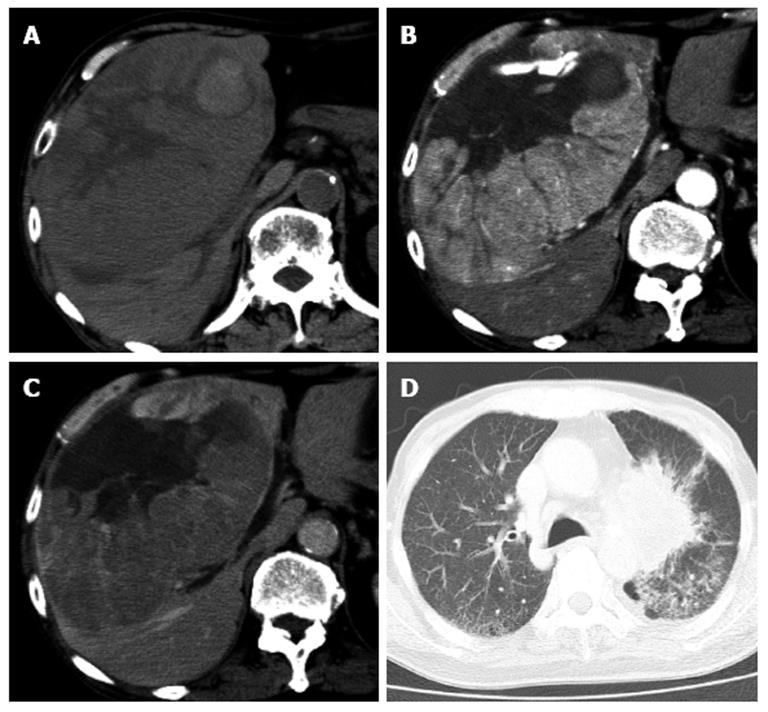

One month previously, hepatic CECT with arterial phase and portal phase revealed a huge HCC (16 cm × 16 cm) in the right liver lobe (Figure 1). His hepatic function was classified as “A” according to the Child-Pugh classification. On physical examination, a non-tender smooth-surfaced mass was palpated at the right upper abdomen. Laboratory results on admission showed that hemoglobin (9.0 g/dL) and albumin (2.9 g/dL) levels were low. His coagulation time was normal, although liver function studies were slightly abnormal. Serological studies for hepatitis viral markers were negative (Hepatitis B surface antigen and Hepatitis C virus antibody). Alpha-fetoprotein and protein-induced vitamin K absence II were 1717 ng/mL and 337000 mAU/mL, respectively. Because of his clinical signs and advanced lung cancer, a surgical resection could not be performed. Thus, TACE was offered to this patient.

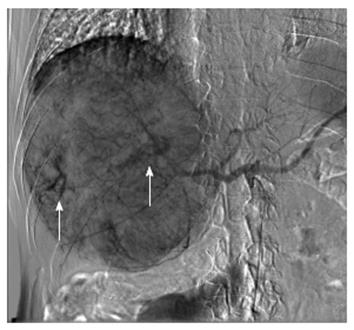

Angiography demonstrated that the huge HCC was supplied from the right hepatic artery (RHA) and right inferior phrenic artery (RIP), concomitant with arteriovenous shunting (Figure 2). TACE was performed through RHA and RIP using an emulsion of miriplatin (70 mg) and lipiodol (40 mL). Gelfoam fine particles were injected into the feeding artery. During this procedure, the patient had no complaints, although his peripheral oxygen saturation decreased to 90%. However, after this operation, the patient immediately experienced dyspnea and he required a non-rebreathing mask. The clinical picture suggested acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

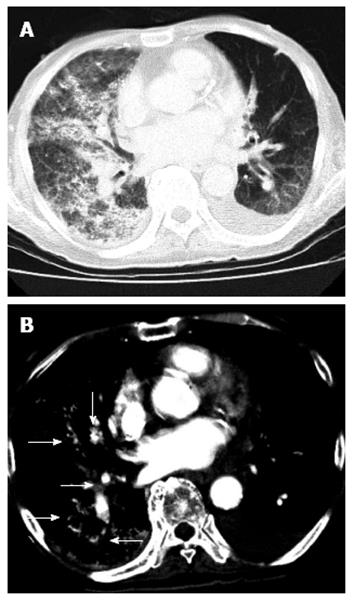

A chest CT scan revealed diffuse increased attenuation and interstitial thickening. There was also an accumulation of multiple iodized oil-like high-density materials, particularly in the right lung lobe (Figure 3). This patient underwent bilevel positive airway pressure, and methylprednisolone (1000 mg/d) was administered. Despite vigorous resuscitation and immediate artificial ventilation, this patient’s condition did not improve, and he died the following day. After his death, written consent was obtained from his relatives, and we performed an autopsy to investigate the underlying pathological condition.

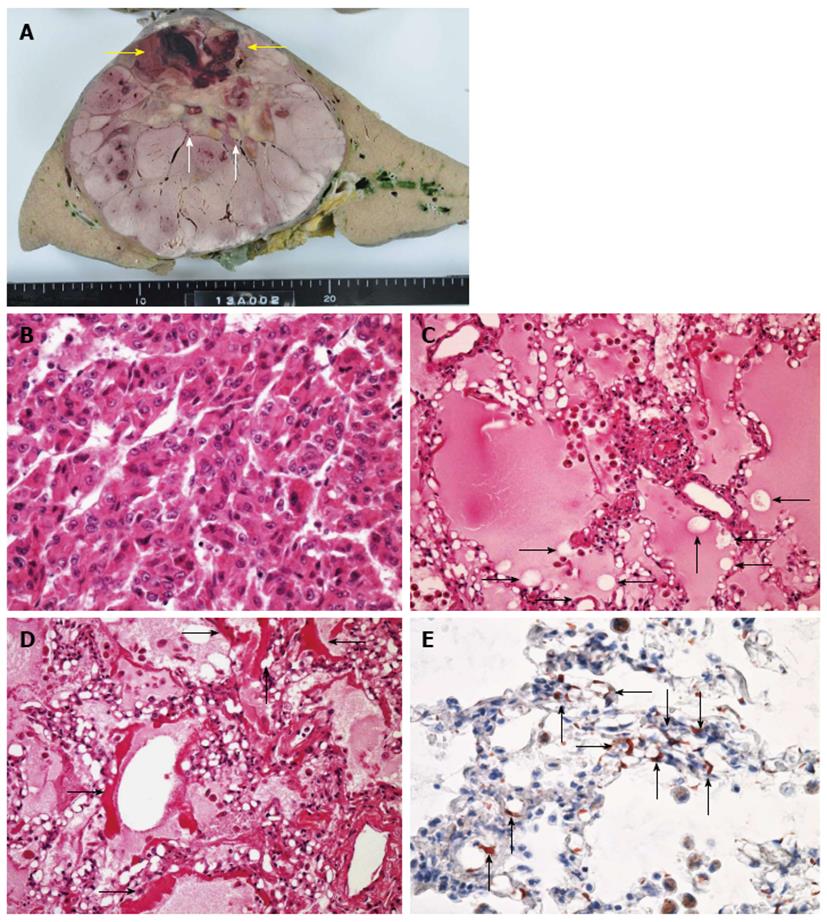

Histopathological micrographs revealed pathological changes in the lung. Hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) staining showed alveolar hemorrhagic edema with fat droplet deposition and fibrin thrombi. Fat staining showed multiple fatty droplets in the lung. Fat specific staining with Sudan III indicated fat droplets in the pulmonary arteriolar lumen (Figure 4). His huge liver tumor was a moderately differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma with hemorrhage and necrosis, although the background of the liver was normal.

TACE is associated with several severe complications. ARDS associated with a pulmonary lipiodol embolism that develops after TACE is one of the most severe of these complications. The incidence of symptomatic pulmonary lipiodol embolism after TACE is in the range of 0.05%-1.8%[1,2], and ARDS that develops due to pulmonary lipiodol embolism is extremely rare. The respiratory symptoms that have been reported were non-specific including dyspnea, cough, tachypnea, and hemoptysis. A previous report showed that the onset of respiratory distress symptoms occurred within 2-5 d[1]. For our case, respiratory symptoms were apparent within two hours after TACE.

The mechanisms underlying symptomatic pulmonary injury associated with TACE are not well understood. The most likely mechanism is chemical injury caused by free fatty acid components. This develops because a high concentration of unbound free fatty acids released from the breakdown of oil microemboli may lead to pulmonary capillary leakage[1]. Most hypotheses for the pathogenesis of lung injury due to fat embolisms are related to the toxicity of free fatty acids. Silvestri et al[3] and Clouse et al[4] reported on inflammatory reactions to iodized oil. Kao et al[5,6] reported on patients who suffered from traumatic injuries and developed fat embolism syndrome with fulminant ARDS within 2 h. They suggested that nitric oxide (NO), phospholipase A2, free radicals, and pro-inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β, interleukin-10) played a role in the pathogenesis of fat embolism syndrome-induced ARDS. They also proposed that alveolar macrophages were probably the major source of inducible nitric oxide synthase for producing NO in the lung. For our case, histopathological micrographs of the lung showed that alveolar capillaries were focally distended by iodized oil. We speculate that the etiology of lung injury after TACE is similar to the pathological conditions associated with fat embolism syndrome.

The risk factors for pulmonary lipiodol embolism after TACE include the amount of lipiodol that is injected, arteriovenous shunting in a tumor, and communication between the inferior phrenic artery and the pulmonary artery[7-9]. Chung et al[1] proposed that the amount of injected lipiodol was the most important among these risk factors. They recommended that the amount of lipiodol used should be less than 20 mL (0.25 mL/kg). They also demonstrated that using more than 0.3 mL/kg of lipiodol was associated with the development of pulmonary lipiodol embolism in 43% of their patients. For our case, the amount of lipiodol injected was 40 mL, which was greater than the amount recommended by Chung et al[1].

Another risk factor for pulmonary lipiodol embolism is arteriovenous shunting in a tumor. It is considered that the communication between a tumor feeding artery and the hepatic vein leads to pulmonary lipiodol embolism after TACE. In addition, the communication between the inferior phrenic artery and the pulmonary artery is similar. Vascular abnormalities can be found in patients with advanced liver disease or a huge HCC[10]. Ho et al[11] demonstrated that lung shunting was influenced by the type, size, and vascularity of HCC. With HCC, mean lung shunting increases with increasing tumor size, up to 15 cm, although mean lung shunting remains nearly unchanged up to a tumor size of > 20 cm. Mean lung shunting also increases with increased vascularity grades.

To reduce the effect of arteriovenous shunting, Lee et al[12] reported that temporary balloon occlusion of the hepatic vein with arteriovenous shunting prevented pulmonary complications during TACE. For our case, we speculate that lipiodol had passed through the hepatic arteriovenous shunt, and subsequently entered the systemic circulation. Thus, our patient suffered from a pulmonary embolism. Therefore, we should pay more attention to those patients who receive injections with large amounts of lipiodol, particularly if they have intrahepatic arteriovenous shunting, large tumors, and abundant tumor vascularity.

Unfortunately, there is no definitive, effective therapy for pulmonary lipiodol embolism. Yamaura et al[7] used heparin, nitroglycerine, furosemide, high-dose methylprednisolone, and mechanical ventilation with positive end-expiratory pressure and pressure support. Shiah et al[13] used oxygenation and high-dose methylprednisolone. Although these treatments may facilitate the recovery from a fulminant pulmonary lipiodol embolism with ARDS, they have not been shown to reduce the morbidity or mortality associated with this condition.

In conclusion, pulmonary lipiodol embolism after TACE is rare, although it can be a fatal complication. To prevent this complication, it is important to consider the therapeutic strategy with regard to the following points: limiting the amount of lipiodol injected and evaluating for the presence of arteriovenous shunting.

A 77-year-old man who was diagnosed with a huge hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Hepatocellular carcinoma.

Metastatic liver cancer.

Alpha-fetoprotein and protein-induced vitamin K absence II were 1717 ng/mL and 337000 mAU/mL, respectively.

Hepatic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) with arterial phase and portal phase revealed a huge HCC (16 cm × 16 cm) in the right liver lobe. After the transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, chest CT scan revealed diffuse increased attenuation and interstitial thickening.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed alveolar hemorrhagic edema with fat droplet deposition and fibrin thrombi. Fat staining showed multiple fatty droplets in the lung. Fat specific staining with Sudan III indicated fat droplets in the pulmonary arteriolar lumen.

This patient underwent bilevel positive airway pressure, and methylprednisolone (1000 mg/d) was administered.

To prevent pulmonary lipiodol embolism after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, it is important to consider the therapeutic strategy.

This paper reports on a rare case of pulmonary lipiodol embolism with acute respiratory distress syndrome after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for HCC. It is a rare case and autopsy was performed to explain the probable mechanism of pulmonary lipiodol embolism.

P- Reviewer: Chen Y, Sugawara Y S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Chung JW, Park JH, Im JG, Han JK, Han MC. Pulmonary oil embolism after transcatheter oily chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiology. 1993;187:689-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Xia J, Ren Z, Ye S, Sharma D, Lin Z, Gan Y, Chen Y, Ge N, Ma Z, Wu Z. Study of severe and rare complications of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for liver cancer. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:407-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Silvestri RC, Huseby JS, Rughani I, Thorning D, Culver BH. Respiratory distress syndrome from lymphangiography contrast medium. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;122:543-549. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Clouse ME, Hallgrimsson J, Wenlund DE. Complications following lymphography with particular reference to pulmonary oil embolization. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1966;96:972-978. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Kao SJ, Yeh DY, Chen HI. Clinical and pathological features of fat embolism with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Clin Sci (Lond). 2007;113:279-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kao SJ, Chen HI. Nitric oxide mediates acute lung injury caused by fat embolism in isolated rat’s lungs. J Trauma. 2008;64:462-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yamaura K, Higashi M, Akiyoshi K, Itonaga Y, Inoue H, Takahashi S. Pulmonary lipiodol embolism during transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatoblastoma under general anaesthesia. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2000;17:704-708. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Czauderna P, Zbrzezniak G, Narozanski W, Sznurkowska K, Skoczylas-Stoba B, Stoba C. Pulmonary embolism: a fatal complication of arterial chemoembolization for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1647-1650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tajima T, Honda H, Kuroiwa T, Yabuuchi H, Okafuji T, Yosimitsu K, Irie H, Aibe H, Masuda K. Pulmonary complications after hepatic artery chemoembolization or infusion via the inferior phrenic artery for primary liver cancer. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:893-900. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Lange PA, Stoller JK. The hepatopulmonary syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:521-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ho S, Lau WY, Leung WT, Chan M, Chan KW, Johnson PJ, Li AK. Arteriovenous shunts in patients with hepatic tumors. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1201-1205. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Lee JH, Won JH, Park SI, Won JY, Lee do Y, Kang BC. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma with hepatic arteriovenous shunt after temporary balloon occlusion of hepatic vein. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:377-382. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Shiah HS, Liu TW, Chen LT, Chang JY, Liu JM, Chuang TR, Lee WS, Whang-Peng J. Pulmonary embolism after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2005;14:440-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |