Published online Oct 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i39.11152

Peer-review started: April 20, 2015

First decision: June 19, 2015

Revised: July 2, 2015

Accepted: September 2, 2015

Article in press: September 2, 2015

Published online: October 21, 2015

Processing time: 183 Days and 18.3 Hours

AIM: To investigate the relationship between serum vitamin D3 levels and liver fibrosis or inflammation in treatment-naive Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC).

METHODS: From July 2010 to June 2011, we enrolled 122 CHC patients and 11 healthy controls from Dingxi city, Gansu Province, China. The patients were infected with Hepatitis C virus (HCV) during blood cell re-transfusion following plasma donation in 1992-1995, and had never received antiviral treatment. At present, all the patients except two underwent liver biopsy with ultrasound guidance. The Scheuer Scoring System was used to evaluate hepatic inflammation and the Metavir Scoring System was used to evaluate hepatic fibrosis. Twelve-hour overnight fasting blood samples were collected in the morning of the day of biopsy. Serum levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, cholinesterase, prothrombin activity, albumin, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, hemoglobin, calcium and phosphorus were determined. Serum HCV RNA levels were measured by real-time PCR. Serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 [25(OH)D3] and 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [24,25(OH)2D3] were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry.

RESULTS: Serum levels of 25(OH)D3 but not 24,25(OH)2D3 were significantly lower in CHC patients than in control subjects. Serum 25(OH)D3 levels did not correlate with liver fibrosis, inflammation, patient age, or levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, prothrombin activity, cholinesterase or HCV RNA. However, serum 25(OH)D3 levels did correlate with serum 24,25(OH)2D3 levels. Serum 25(OH)D3 and 24,25(OH)2D3 levels, and the 25(OH)D3/24,25(OH)2D3 ratio, have no difference among the fibrosis stages or inflammation grades.

CONCLUSION: We found that serum levels of 25(OH)D3 and its degradation metabolite 24,25(OH)2D3 did not correlate with liver fibrosis in treatment-naive Chinese patient with CHC.

Core tip: We studied the relationship between liver fibrosis, based on liver biopsies, and serum vitamin D3 levels in Chinese treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC). The levels of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 [25(OH)D3] were significantly lower in the patients than in healthy control subjects. The levels of the degradation metabolite 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [24,25(OH)2D3] did not differ between the patients and controls. Spearman’s rank correlation analysis indicated that serum 25(OH)D3 levels did not correlate with the extent of liver fibrosis or inflammation. However, serum 25(OH)D3 levels did correlate with serum 24,25(OH)2D3 levels. Serum 25(OH)D3 and 24,25(OH)2D3 levels, and the 25(OH)D3/24,25(OH)2D3 ratio, have no difference among the fibrosis stages or inflammation grades. In conclusion, the levels of serum 25(OH)D3 and its metabolite 24,25(OH)2D3 did not correlate with liver fibrosis in treatment-naive Chinese patient with CHC.

- Citation: Ren Y, Liu M, Zhao J, Ren F, Chen Y, Li JF, Zhang JY, Qu F, Zhang JL, Duan ZP, Zheng SJ. Serum vitamin D3 does not correlate with liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(39): 11152-11159

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i39/11152.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i39.11152

Vitamin D has many functions in addition to regulating the metabolism of calcium and phosphorus, such as immunomodulatory and anti-proliferative activities[1]. The liver plays an important role in vitamin D metabolism. Vitamin D3 is obtained through food intake, and 7-dehydrocholesterol in skin can be converted into vitamin D3 after exposure to ultraviolet light. Vitamin D3 is hydroxylated to 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 [25(OH)D3] in the liver. 25(OH)D3 is further hydroxylated to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3] by 1-α-hydroxylase in the kidneys. It is this form of vitamin D that binds to receptors and plays a biological role. Both 25(OH)D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3 can be converted into 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [24,25(OH)2D3], which is an inactive form of vitamin D3[2].

Recent studies have found that there is a close relationship between vitamin D and hepatitis C[3-6]. Although it is accepted that patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) have low serum levels of 25(OH)D3, there are inconsistencies regarding its role in liver fibrosis. Several studies have shown that the low serum levels of 25(OH)D3 in CHC patients are associated with the progression or degree of liver fibrosis and the response of hepatitis C virus (HCV) to antiviral therapy[7,8]. In contrast, other studies have found no correlation between vitamin D levels and either liver fibrosis or sustained virological responses[9,10].

The association of 24,25(OH)2D3 levels with liver fibrosis in CHC has not been reported. This is an interesting issue that should be addressed, as 24,25(OH)2D3 is downstream in the vitamin D metabolic pathway.

Because vitamin D levels and fibrosis are affected by many factors such as race, diet, light exposure, measurement methods, and interferon treatment, there is an urgent need to evaluate the role of vitamin D in liver fibrosis in patients with CHC. To date, the correlation between serum 25(OH)D3 levels and liver fibrosis, based on liver biopsy, has rarely been reported in Chinese Han patients with CHC.

In this study, we enrolled 122 patients with CHC who were naïve to antiviral treatment and 11 healthy controls. All of the subjects were of Han ethnicity and living in the same area of Dingxi, Gansu Province, with similar environmental and eating habits. The purpose of this study was to measure 25(OH)D3 and 24,25(OH)2D3 serum levels in Chinese Han patients with CHC, and to analyze the correlation between these levels and liver fibrosis or inflammation.

From July 2010 to June 2011, we enrolled 122 CHC patients and 11 healthy controls from Dingxi city, Gansu Province, China. These patients were infected with HCV during blood cell re-transfusion following plasma donation in 1992-1995, and had never received antiviral therapy. The diagnosis of CHC was made according to the established criteria[11,12]. Patients were excluded from the study if they had liver disease of mixed or other etiology, such as hepatitis B, autoimmune liver disease, excessive alcohol consumption, or Wilson’s disease, or if the patients had hepatocellular carcinoma or other malignant diseases. Patients with vitamin D supplementation or other medical therapy that influences vitamin D metabolism were also excluded.

All CHC patients and healthy controls gave informed consent before the study. The study protocol was in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and its appendices. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing YouAn Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China.

CHC patients underwent liver biopsy with ultrasound guidance. The biopsy specimens had a minimum length of 15 mm and contained at least six complete portal tracts. Two patients were excluded from pathological analysis: one because of ascites, and the other because the liver biopsy was too small. Thus, 120 patients were included for further assessment. The liver sections stained by hematoxylin and eosin. Slides were coded and read by two pathologists who were unaware of the patient’s identity and history. The Scheuer Scoring System was used to evaluate hepatic inflammation and the Metavir Scoring System was used to evaluate hepatic fibrosis. A fibrosis score of F ≥ 2 was defined as moderate fibrosis, and F ≥ 3 was defined as severe fibrosis.

Twelve-hour overnight fasting blood samples were collected in the morning of the day of biopsy. Serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin (TBIL), direct bilirubin (DBIL), cholinesterase, prothrombin activity (PTA), albumin, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), calcium and phosphorus were determined by automated biochemical detection. Blood cell counts were determined by multi-parameter auto-calculator. Serum HCV RNA levels were determined by real-time PCR.

Blood samples for vitamin D measurements were collected at the same time as the blood samples for clinical parameter measurements. Serum samples were stored at -80 °C, then 25(OH)D3 and 24,25(OH)2D3 levels were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) at the State Key Laboratory of Bioactive Substance and Function of Natural Medicines, Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China. All vitamin D standards were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, United States). HPLC-MS/MS was performed on an Agilent 6410B Triple Quad mass spectrometer (QQQ; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States) containing a triple quadrupole MS analyzer with an electrospray ionization interface and an Agilent 1200 RRLC system.

Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables were summarized as frequency and percentage. Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare continuous variables when appropriate. Correlations were evaluated with the Spearman rank coefficient. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used SPSS version 18.0 (Chicago, IL, United States).

The clinical features of the 120 patients who underwent liver biopsy and 11 healthy controls are shown in Table 1. The male-to-female ratio of the patients was 57/63, with a mean age of 51.33 ± 7.33 years. The Metavir fibrosis scores were: F0 (1/120, 0.8%), F1 (55/120, 45.8%), F2 (50/120, 47.1%), F3 (12/120, 10%), and F4 (2/120, 1.7%). The inflammation grades were: G0 (1/120, 0.8%), G1 (16/120, 13.3%), G2 (67/120, 55.8%), G3 (34/120, 28.3%), and G4 (2/120, 1.7%).

| Features | Patients (n = 120) | Controls (n = 11) |

| Male/female | 57/63 | 4/7 |

| Age (yr) | 51.33 ± 7.33 | 38.45 ± 6.95 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.34 ± 2.73 | 24.00 ± 2.53 |

| ALT (U/L) | 60.42 ± 70.88 | 16.71 ± 5.14 |

| AST (U/L) | 47.94 ± 44.30 | 19.87 ± 3.49 |

| TBIL (µmol/L) | 16.51 ± 7.25 | 16.30 ± 5.64 |

| DBIL (µmol/L) | 3.26 ± 1.36 | 2.82 ± 0.75 |

| TP (g/L) | 70.93 ± 4.95 | 69.05 ± 3.15 |

| ALB (g/L) | 43.24 ± 2.36 | 43.86 ± 2.18 |

| GGT (U/L) | 22.04 ± 16.50 | 15.90 ± 10.82 |

| CHE (U/L) | 6657.09 ± 1442.44 | 7703.45 ± 945.75 |

| Ca (mmol/L) | 2.26 ± 0.08 | 2.21 ± 0.05 |

| P (mmol/L) | 0.92 ± 0.19 | 1.02 ± 0.14 |

| HB (g/L) | 151.09 ± 16.56 | 144.45 ± 11.43 |

| PLT (× 109/L) | 171.36 ± 53.20 | 242.18 ± 48.36 |

| PTA (%) | 92.41 ± 9.11 | 93.78 ± 4.69 |

| Virus load, n (%) | ||

| < 4 log10 | 20 (16.7) | |

| 4-5 log10 | 52 (43.3) | |

| 6-7 log10 | 48 (40.0) | |

| Stage of fibrosis, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 1 (0.8) | |

| 1 | 55 (45.8) | |

| 2 | 50 (47.1) | |

| 3 | 12 (10) | |

| 4 | 2 (1.7) | |

| Grade of inflammation, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 1 (0.8) | |

| 1 | 16 (13.3) | |

| 2 | 67 (55.8) | |

| 3 | 34 (28.3) | |

| 4 | 2 (1.7) |

The average level of serum 25(OH)D3 in the patients with CHC was 5.84 ± 2.63 ng/mL, which was lower than that of the healthy controls (10.08 ± 3.15 ng/mL) (z = -3.93, P < 0.001). The average level of serum 24,25(OH)2 D3 did not differ significantly between the patients and controls (1.78 ± 1.02 ng/mL vs 2.30 ± 1.27 ng/mL, z = -1.40, P = 0.161). The ratio of 25(OH)D3 to 24,25(OH)2D3 also did not differ significantly between the two groups (4.10 ± 2.44 vs 5.52 ± 2.47, P = 0.076) (Table 2).

| Patients(n = 120) | Controls(n = 11) | P value | |

| 25(OH)D3 (ng/mL) | 5.84 ± 2.63 | 10.08 ± 3.15 | < 0.001 |

| 24,25(OH)2D3 (ng/mL) | 1.78 ± 1.02 | 2.30 ± 1.27 | 0.161 |

| 25(OH)D3/24,25(OH)2D3 | 4.10 ± 2.44 | 5.52 ± 2.47 | 0.076 |

Spearman’s rank correlation analysis showed that neither 25(OH)D3 nor 24,25(OH)2D3 correlated with patient age or level of ALT, AST, TBIL, DBIL, PTA, cholinesterase, or HCV RNA. The 25(OH)D3/24,25(OH)2D3 ratio correlated negatively with the serum levels of ALT (r = -0.230, P = 0.012), TBIL (r = -0.176, P = 0.054), DBIL (r = -0.282, P = 0.002), total protein (r = -0.185, P = 0.043), and GGT (r = -0.211, P = 0.021). Serum 25(OH)D3 levels correlated positively with the levels of 24,25(OH)2D3 (r = 0.410, P < 0.001) (Table 3).

| 25(OH)D3 (ng/mL) | 24,25(OH)2D3 (ng/mL) | 25(OH)D3/24,25(OH)2D3 | ||||

| r value | P value | r value | P value | r value | P value | |

| Age (yr) | -0.034 | 0.711 | -0.132 | 0.150 | -0.134 | 0.145 |

| ALT (U/L) | -0.062 | 0.502 | 0.175 | 0.055 | -0.230 | 0.012 |

| AST (U/L) | 0.036 | 0.693 | 0.169 | 0.066 | -0.149 | 0.104 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | -0.124 | 0.177 | 0.088 | 0.337 | -0.176 | 0.054 |

| DBIL (μmol/L) | -0.165 | 0.072 | 0.109 | 0.065 | -0.282 | 0.002 |

| TP (g/L) | -0.126 | 0.170 | 0.136 | 0.138 | -0.185 | 0.043 |

| ALB (g/L) | 0.027 | 0.770 | 0.120 | 0.193 | -0.112 | 0.223 |

| GGT (U/L) | -0.143 | 0.119 | 0.104 | 0.260 | -0.211 | 0.021 |

| CHE (U/L) | -0.015 | 0.871 | -0.058 | 0.526 | -0.011 | 0.906 |

| Ca (mmol/L) | 0.027 | 0.768 | 0.200 | 0.028 | -0.158 | 0.084 |

| P (mmol/L) | 0.088 | 0.337 | -0.130 | 0.158 | 0.266 | 0.003 |

| HB (g/L) | -0.040 | 0.665 | 0.133 | 0.149 | -0.195 | 0.033 |

| PTA (%) | 0.109 | 0.237 | -0.134 | 0.145 | 0.231 | 0.011 |

| Liver fibrosis | -0.052 | 0.574 | 0.023 | 0.807 | -0.072 | 0.435 |

| Liver inflammation | -0.104 | 0.258 | -0.129 | 0.160 | 0.069 | 0.451 |

| Viral load( IU/mL) | 0.074 | 0.464 | 0.173 | 0.086 | -0.131 | 0.196 |

| 25(OH)D3 (ng/mL) | - | - | 0.410 | < 0.001 | - | - |

| 24,25(OH)2D3 (ng/mL) | 0.410 | < 0.001 | - | - | - | - |

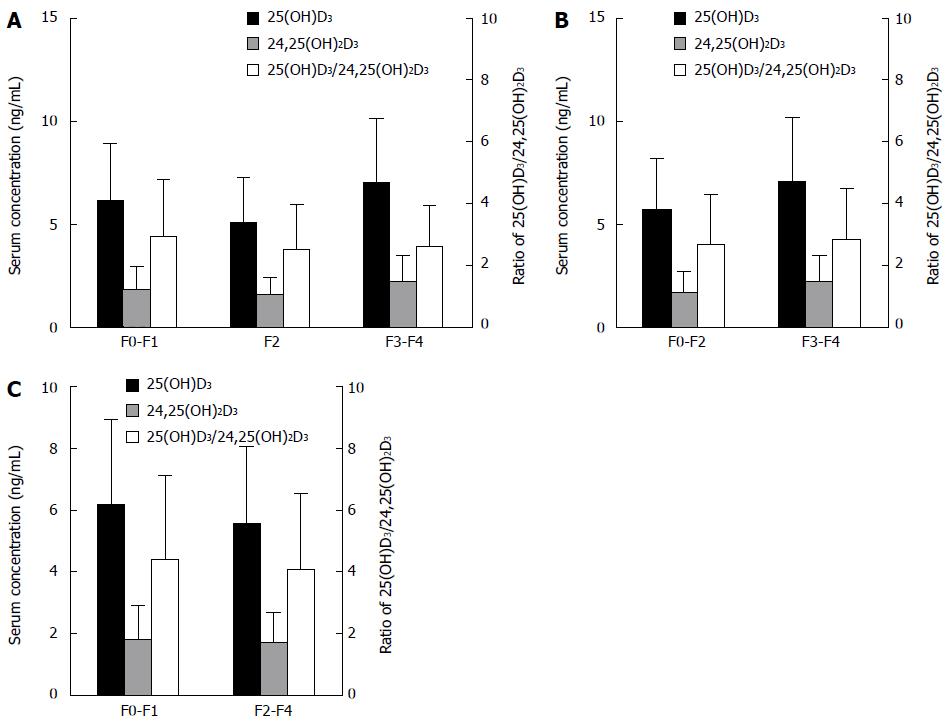

Spearman’s rank coefficient analysis showed that serum 25(OH)D3 levels did not correlate with liver fibrosis (P = 0.574). Although serum 25(OH)D3 levels exhibited some variation with fibrosis stage (F0-F1 vs F2 vs F3-F4, P = 0.027) (Figure 1A), the changing trend in serum 25(OH)D3 levels was not consistent: 25(OH)D3 levels were lower in F2 (5.12 ± 2.15 ng/mL) than in F0-F1 (6.17 ± 2.76 ng/mL) and F3-F4 (7.06 ± 3.10 ng/mL). Further analysis indicated that there was no difference in serum 25(OH)D3 levels between non-severe and severe fibrosis patients (F0-F2 vs F3-F4) (Figure 1B) and between mild and apparent fibrosis patients (F0-F1 vs F2-F4) (Figure 1C).

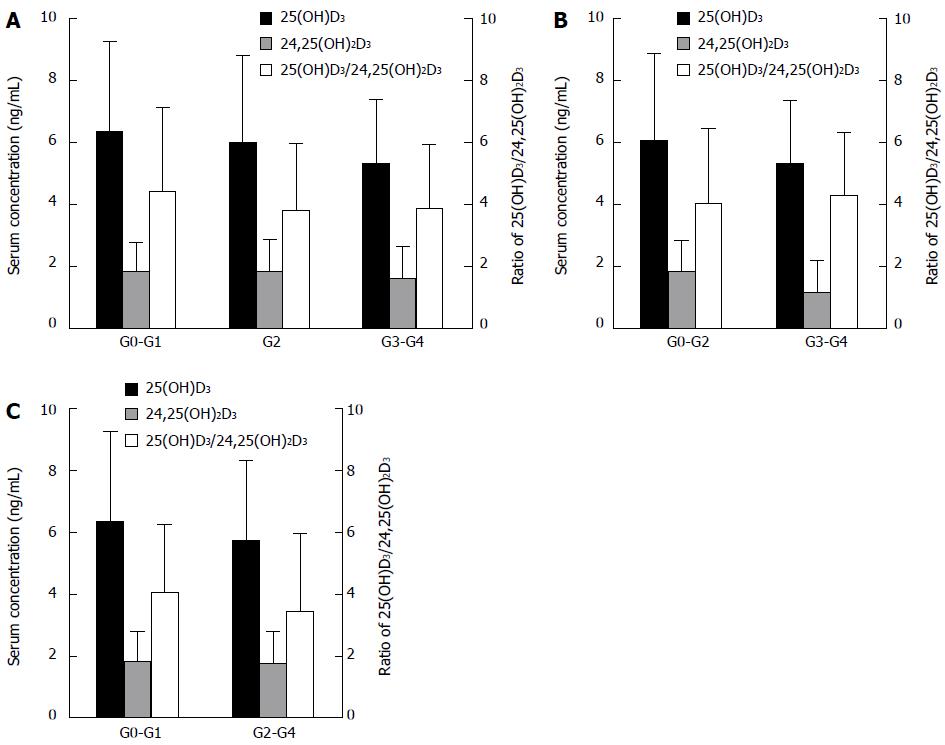

To explore the association of serum 25(OH)D3 levels with liver inflammation, we made multiple comparisons among the different liver inflammation subgroups. However, serum 25(OH)D3 levels did not vary significantly among the inflammation grades (G0-G1 vs G2 vs G3-G4; or G0-G2 vs G3-G4; or G0-G1 vs G2-G4) (Figure 2).

Similarly, serum 24,25(OH)2D3 levels and the ratio of 25(OH)D3 to 24,25(OH)2D3 have no difference among the fibrosis stages or inflammation grades (Figures 1 and 2).

We enrolled Chinese Han subjects from the same geographical area, with similar lifestyles, eating habits and living environments. All the CHC patients had the same route of infection, by plasma donation in 1992-1995, and had never received antiviral treatment. All factors influencing the level of vitamin D and liver fibrosis were adjusted to a similar level or eliminated as far as possible; therefore, we were able to obtain the true results of changes in serum vitamin D levels and their association with liver fibrosis. Liver biopsy and HPLC-MS/MS showed that the serum 25(OH)D3 level had no correlation with fibrosis stage or inflammation grade in the Chinese Han CHC patients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show that there is no difference in serum 24,25(OH)2D3 levels between healthy individuals and CHC patients, and that the serum 24,25(OH)2D3 level does not correlate with liver fibrosis and inflammation.

Although increasing evidence has confirmed that CHC patients are deficient in vitamin D[13-15], the relationship between vitamin D deficiency and liver fibrosis is still unclear. There are several inconsistencies in the literature regarding the role of vitamin D in liver fibrosis[16]. Some studies found a correlation between vitamin D levels and hepatitis C progression[17-19], but other studies found the contrary[9,20,21]. The main reasons for the inconsistencies are that the level of vitamin D can be affected by many factors, such as race, diet, altitude, light exposure, etc.[22], and that liver fibrosis is influenced by co-existing etiologies such as co-infection of HIV, antiviral treatment, and the method of measurement. The HPLC-MS/MS method we employed is currently the best way to detect vitamin D, being more stable, reproducible, sensitive and accurate than other methods[23-26]. The use of HPLC-MS/MS in our study laid a solid foundation for investigating the relationship between vitamin D levels and liver fibrosis in patients with CHC.

Our results showed that CHC patients had lower serum 25(OH)D3 levels than did healthy controls, which is consistent with previous findings[15,27]. In fact, the serum 25(OH)D3 levels in our CHC patients were lower than the levels reported for CHC patients in previous studies. One reason for this difference might be that our patients were of Chinese Han ethnicity, not Caucasian. A recent study found serum 25(OH)D3 levels in healthy Japanese adults to be 34.7 ± 16.4 nmol/L (13.88 ± 6.56 ng/mL), similar to our results[28]. Another reason might be the inadequate nutrition in our patients, due to their low income. We previously found that the mean body mass index (BMI) of our patients was 22.34 kg/m2, which was classified as non-obese (BMI < 25 kg/m2); the liver biopsies in the current study confirmed that 70.0% (84/120) of the patients did not have steatosis[29].

Based on liver biopsy, our study showed no association between serum 25(OH)D3 levels and the degree of liver fibrosis in Chinese Han patients with CHC. This is consistent with the study of Kitson et al[9], in which HPLC-MS/MS was used to measure vitamin D3.

Although serum 25(OH)D3 levels also did not correlate with the grade of inflammation, we found that, from G0-G1 to G2 to G3-G4, the mean serum 25(OH)D3 level changed from 6.35 ± 2.91 ng/mL to 5.99 ± 2.81 ng/mL to 5.31 ± 2.07 ng/mL. This did not exclude the effect of a small sample size in our study. Several studies have shown that severe liver inflammation can decrease 25-hydroxylase activity[9,30], thereby causing a decrease in 25(OH)D3 levels. Further research is needed to elucidate the exact mechanism involved.

Furthermore, we measured serum 24,25(OH)2D3 levels and evaluated whether they were associated with liver fibrosis. Serum 24,25(OH)2D3 is the inactivated form of vitamin D. By measuring the level of 24,25(OH)2D3, we can infer whether there is excessive conversion of 25(OH)D3 in patients with CHC. Although an obvious correlation exists between serum 25(OH)D3 and 24,25(OH)2D3 levels, due to their metabolic connection, we found no difference in serum 24,25(OH)2D3 levels between CHC patients and healthy controls. In order to clarify the phenomenon, future studies should address whether the hydroxylase plays a key role in 24,25(OH)2D3 production.

Similar to serum 25(OH)D3, neither serum 24,

25(OH)2D3 nor the ratio of 25(OH)D3 to 24,25(OH)2D3 correlated with liver fibrosis or inflammation. The serum 24,25(OH)2D3 levels did not differ among the subgroups of liver fibrosis or inflammation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on serum 24,25(OH)2D3 levels and the 25(OH)D3/24,25(OH)2D3 ratio in CHC patients.

There were some limitations in our study. We analyzed the relationship between serum vitamin D and hepatic fibrosis based on a long-term (about 20 years) follow-up in a cohort of treatment-naive CHC patients, and the actual number of patients was not large. The patient and control groups were not well-matched for age. Studies with larger group sizes are needed to verify our findings.

In conclusion, using liver biopsy and HPLC-MS/MS, we found that serum levels of 25(OH)D3 and its degradation metabolite 24,25(OH)2D3 did not correlate with liver fibrosis or inflammation in treatment-naive Chinese Han CHC patients from the same geographical area with similar lifestyle and eating habits.

The liver plays an important role in vitamin D metabolism. Recent studies have found that there is a close relationship between vitamin D and hepatitis C. Although the serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 [25(OH)D3] are known to be decreased in patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC), the role of 25(OH)D3 in liver fibrosis is unclear. Correlation studies on serum 25(OH)D3 levels and liver fibrosis based on liver biopsy in Chinese Han patients with CHC have scarcely been reported.

It is important to study the relationship between vitamin D and liver fibrosis in CHC patients. Several studies showed that the low 25(OH)D3 serum levels in patient with CHC were associated with the progression or degree of liver fibrosis and affected the virological response to anti-HCV therapy. In contrast, other studies found no correlation between serum 25(OH)D3 levels and liver fibrosis or sustained virological responses.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report evaluating the correlation between serum 24,25(OH)2D3 levels, and the 25(OH)D3/24,25(OH)2D3 ratio, with liver fibrosis and inflammation in CHC patients.

The serum levels of 25(OH)D3 and its degradation metabolite 24,25(OH)2D3 cannot be used to predict the extent of liver fibrosis or inflammation in treatment-naive Chinese patient with CHC.

The manuscript by Yan et al is a well-written manuscript with novel data.

P- Reviewer: He JY, Nair Dileep G S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Adams JS, Hewison M. Unexpected actions of vitamin D: new perspectives on the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008;4:80-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 589] [Cited by in RCA: 565] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Christakos S, Dhawan P, Benn B, Porta A, Hediger M, Oh GT, Jeung EB, Zhong Y, Ajibade D, Dhawan K. Vitamin D: molecular mechanism of action. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1116:340-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pappa HM, Bern E, Kamin D, Grand RJ. Vitamin D status in gastrointestinal and liver disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:176-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gutierrez JA, Parikh N, Branch AD. Classical and emerging roles of vitamin D in hepatitis C virus infection. Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31:387-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lim LY, Chalasani N. Vitamin d deficiency in patients with chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:67-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kitson MT, Roberts SK. D-livering the message: the importance of vitamin D status in chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;57:897-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lange CM, Bojunga J, Ramos-Lopez E, von Wagner M, Hassler A, Vermehren J, Herrmann E, Badenhoop K, Zeuzem S, Sarrazin C. Vitamin D deficiency and a CYP27B1-1260 promoter polymorphism are associated with chronic hepatitis C and poor response to interferon-alfa based therapy. J Hepatol. 2011;54:887-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nimer A, Mouch A. Vitamin D improves viral response in hepatitis C genotype 2-3 naïve patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:800-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kitson MT, Dore GJ, George J, Button P, McCaughan GW, Crawford DH, Sievert W, Weltman MD, Cheng WS, Roberts SK. Vitamin D status does not predict sustained virologic response or fibrosis stage in chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 infection. J Hepatol. 2013;58:467-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Corey KE, Zheng H, Mendez-Navarro J, Delgado-Borrego A, Dienstag JL, Chung RT. Serum vitamin D levels are not predictive of the progression of chronic liver disease in hepatitis C patients with advanced fibrosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e27144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hepatology Branch, Infectious Disease & Parasitologic Diseases Branch, Chinese Medical Association. [Guideline of prevention and therapy of hepatitis C]. Zhonghua Liuxingbingxue Zazhi. 2004;25:369-375. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335-1374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2320] [Cited by in RCA: 2242] [Article Influence: 140.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Gerova DI, Galunska BT, Ivanova II, Kotzev IA, Tchervenkov TG, Balev SP, Svinarov DA. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in Bulgarian patients with chronic hepatitis C viral infection. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2014;74:665-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Iruzubieta P, Terán Á, Crespo J, Fábrega E. Vitamin D deficiency in chronic liver disease. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:901-915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Villar LM, Del Campo JA, Ranchal I, Lampe E, Romero-Gomez M. Association between vitamin D and hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5917-5924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 16. | White DL, Tavakoli-Tabasi S, Kanwal F, Ramsey DJ, Hashmi A, Kuzniarek J, Patel P, Francis J, El-Serag HB. The association between serological and dietary vitamin D levels and hepatitis C-related liver disease risk differs in African American and white males. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:28-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Avihingsanon A, Jitmitraparp S, Tangkijvanich P, Ramautarsing RA, Apornpong T, Jirajariyavej S, Putcharoen O, Treeprasertsuk S, Akkarathamrongsin S, Poovorawan Y. Advanced liver fibrosis by transient elastography, fibrosis 4, and alanine aminotransferase/platelet ratio index among Asian hepatitis C with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection: role of vitamin D levels. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1706-1714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Guzmán-Fulgencio M, García-Álvarez M, Berenguer J, Jiménez-Sousa MÁ, Cosín J, Pineda-Tenor D, Carrero A, Aldámiz T, Alvarez E, López JC. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with severity of liver disease in HIV/HCV coinfected patients. J Infect. 2014;68:176-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Terrier B, Carrat F, Geri G, Pol S, Piroth L, Halfon P, Poynard T, Souberbielle JC, Cacoub P. Low 25-OH vitamin D serum levels correlate with severe fibrosis in HIV-HCV co-infected patients with chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2011;55:756-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | El-Maouche D, Mehta SH, Sutcliffe CG, Higgins Y, Torbenson MS, Moore RD, Thomas DL, Sulkowski MS, Brown TT. Vitamin D deficiency and its relation to bone mineral density and liver fibrosis in HIV-HCV coinfection. Antivir Ther. 2013;18:237-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Duarte MP, Farias ML, Coelho HS, Mendonça LM, Stabnov LM, do Carmo d Oliveira M, Lamy RA, Oliveira DS. Calcium-parathyroid hormone-vitamin D axis and metabolic bone disease in chronic viral liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:1022-1027. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, Murad MH, Weaver CM. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911-1930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6974] [Cited by in RCA: 6841] [Article Influence: 488.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hsu SA, Soldo J, Gupta M. Evaluation of two automated immunoassays for 25-OH vitamin D: comparison against LC-MS/MS. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;136:139-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Roth HJ, Schmidt-Gayk H, Weber H, Niederau C. Accuracy and clinical implications of seven 25-hydroxyvitamin D methods compared with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry as a reference. Ann Clin Biochem. 2008;45:153-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lensmeyer GL, Wiebe DA, Binkley N, Drezner MK. HPLC method for 25-hydroxyvitamin D measurement: comparison with contemporary assays. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1120-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Vogeser M. Quantification of circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121:565-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Arteh J, Narra S, Nair S. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in chronic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2624-2628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 28. | Sun X, Cao ZB, Zhang Y, Ishimi Y, Tabata I, Higuchi M. Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and inflammatory cytokines in healthy adults. Nutrients. 2014;6:221-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Li JF, Qu F, Zheng SJ, Wu HL, Liu M, Liu S, Ren Y, Ren F, Chen Y, Duan ZP. Elevated plasma sphingomyelin (d18: 1/22: 0) is closely related to hepatic steatosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:1725-1732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Petta S, Cammà C, Scazzone C, Tripodo C, Di Marco V, Bono A, Cabibi D, Licata G, Porcasi R, Marchesini G. Low vitamin D serum level is related to severe fibrosis and low responsiveness to interferon-based therapy in genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2010;51:1158-1167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 325] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |