Published online Sep 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i36.10475

Peer-review started: March 20, 2015

First decision: April 23, 2015

Revised: May 7, 2015

Accepted: July 3, 2015

Article in press: July 3, 2015

Published online: September 28, 2015

Processing time: 192 Days and 11.6 Hours

We report a case of acute severe hepatitis resulting from masitinib in a young amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patient. Hepatotoxicity induced by masitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is usually transient with mild elevation of transaminases, although acute hepatitis has been not reported to date. The hepatitis was resolved after masitinib was discontinued and a combination of prednisone and azathioprine was started. The transaminases returned to baseline normal values five months later. This is the first case in the hepatitis literature associated with masitinib. The autoimmune role of this drug-induced liver injury is discussed. Physicians should be aware of this potential complication.

Core tip: Physicians must be aware of the possibility of drug-induced liver injury in clinical trials, despite the drug having been shown to be of limited hepatotoxicity when tested in phase I-II trials. We present an example of a patient resembling an autoimmune hepatitis. Despite discontinuing masitinib, the transaminases did not return to their baseline values for five months.

- Citation: Salvado M, Vargas V, Vidal M, Simon-Talero M, Camacho J, Gamez J. Autoimmune-like hepatitis during masitinib therapy in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patient. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(36): 10475-10479

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i36/10475.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i36.10475

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a rapidly progressive neurodegenerative disorder predominantly affecting motor neurons, leading to generalized muscle paralysis and death from respiratory failure. Mean survival subsequent to clinical onset is 3-5 years, although patients may survive longer if they accept mechanical ventilation and other aggressive life support measures. The pathogenic processes underlying ALS are multifactorial and not yet fully determined. There is no effective treatment for the disease apart from these measures, except for riluzole, which is the only approved drug for the treatment of ALS, and which prolongs survival by a mere three months. Immunomodulatory drugs have recently been suggested as a possible therapeutic approach in ALS. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled, exploratory phase II/III study of masitinib in patients with ALS treated over 48 wk, with an extension phase, is ongoing. The patients recruited are being randomized to receive placebo or masitinib at an initial dose of 3 or 4.5 mg/kg per day (in combination with riluzole) administered orally in two daily intakes[1].

We report here a case of a young ALS patient treated with riluzole, who presented high transaminase levels of up to 64 times baseline values, compatible with a hepatitic pattern, 12 wk after the introduction of masitinib.

A 40-year-old woman was diagnosed with a predominantly bulbar ALS in October 2011, when she started riluzole 100 mg/d and vitamin E 400 mg/d. Some months later, she started treatment with paroxetine 20 mg due to a reactive depression.

On the 30th December 2013, the patient decided to participate in a clinical trial with masitinib[1]. After signing an informed consent form, and completion and review of all the screening visit assessments, she was randomized to oral masitinib vs placebo 300 mg a day. At that time, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was 14 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was 25 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was 85 IU/L, gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) was 13 IU/L, and total bilirubin was 0.60 mg/dL.

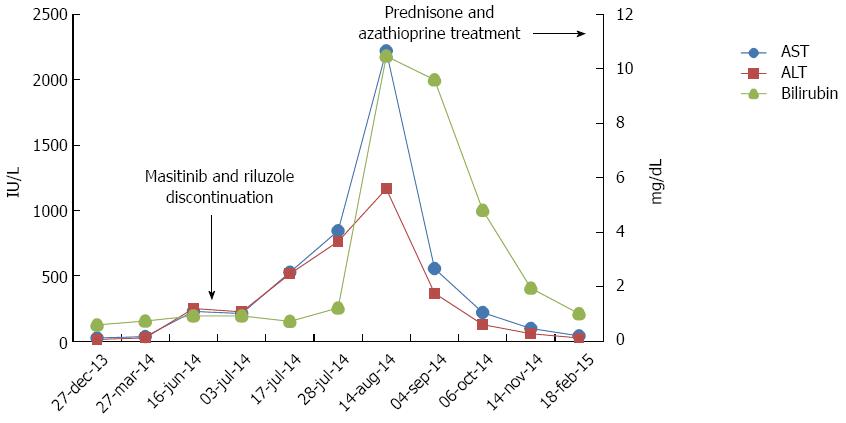

The patient reported mild nausea in the week 12 visit (March 27, 2014). As a result, she was started on metroclopramide 10 mg before meals on demand. Blood test results showed non-clinical significant values. Afterwards, in the scheduled biochemistry blood test in the visit in week 24 (June 16, 2014), she presented elevated transaminases [AST, 228 IU/L (normal values 10-30 IU/L) and ALT, 250 IU/L (normal values 7-34 IU/L). These values were considered severe (grade 3) according to the protocol and administration was consequently discontinued. Riluzole was also discontinued. Treatment was unblinded according to the pharmacovigilance protocol. The patient had been randomized to the masitinib 300 mg/d arm. The transaminase values continued to rise to the following maximum values: AST, 2221 IU/L; ALT, 1166 IU/L; ALP, 240 IU/L; and GGT, 204 IU/L. Bilirubin rose to 10.47 mg/dL.

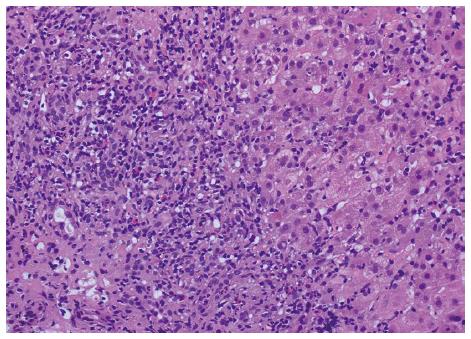

Laboratory screening for viral hepatitis included IgM anti-HAV anti-HCV, HBsAg, anti-HBc, IgM anti-HBc, anti-HEV, IgM anti-HEV, were all negative. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) were negative and immunoglobulins were within normal limits. Liver ultrasonography showed a normal liver parenchyma and normal biliary tract. Hepatic biopsy showed diffuse parenchymal involvement with marked portal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, with neutrophils, numerous eosinophils and only isolated plasma cells, accompanied by extensive interface hepatitis, occasional bridging necrosis and severe lobular necroinflammatory activity. These features suggest an acute drug-induced liver injury with autoimmune-like histological pattern (Figure 1).

After that, the patient started taking oral prednisone 60 mg daily and oral azathioprine 50 mg daily. Treatment with prednisone in combination with azathioprine was chosen, as this combination has been associated with fewer side effects than conventional corticosteroid regimen alone, and reduces exacerbations after discontinuation of immunosuppressive drugs, according to most guidelines and recommendations on managing drug-induced liver injury (DILI) with autoimmune features[2-5]. The patient’s clinical and biochemical status improved with this treatment. Figure 2 shows the evolution of transaminase and bilirubin values. The laboratory values in February 2015 were 41 IU/L (AST), 25 IU/L (ALT), 38 IU/L (GGT), 97 IU/L (ALP) and 1.01 mg/dL (bilirubin).

Masitinib is a highly selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor with anti-tumoral and anti-inflammatory activity. Masitinib is a promising treatment option for patients with solid tumors, particularly GIST[6-9]. Indeed, it is particularly efficient in controlling the survival, migration and degranulation of mast cells (and thus indirectly controlling the array of proinflammatory and vasoactive mediators these cells can release), through inhibition of essential growth and activation signaling pathways[10]. Human clinical trials have been performed in neurological and inflammatory disorders. Promising results have consequently been obtained in Alzheimer’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, progressive multiple sclerosis, and systemic mastocytosis phase II/III clinical trials[11-14]. Masitinib has a good safety profile. The maximum tolerated dose has not yet been reached in phase I studies of healthy volunteers or in cancer patients orally administered up to 1000 mg/d[6]. Dose levels of 7.5 mg/kg per day have shown no significant toxicity. The side-effect profile of masitinib appears to be similar to other tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Those commonly observed in long-term administration were gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting), hematological (anemia, lymphopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia), dermatological (eyelid and facial oedema, rash), and others (pyrexia, jaundice, dehydration, general deterioration in physical health, hypokalaemia, and thrombosis)[1,6-9,11-14]. Liver functions should be closely monitored in patients with impairment, and especially those who are also treated with another cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors.

Our patient had an acute icteric hepatitis with elevated transaminases (> 10 ULN) and bilirubin (> 5 ULN), which can be considered a grade IV hepatotoxicity. Six months after beginning masitinib treatment, she developed a marked elevation of ALT; the drug was discontinued but transaminase levels and bilirubin continued rising for 9 wk. After immunosuppressive therapy, the patient improved and a biochemical remission was observed. Grade 3 and 4 liver adverse events, as in our case, have previously been reported with other tyrosine kinase inhibitor drugs. After a literature review, we found at least 16 cases of severe DILI secondary to other members of the TK inhibitors family, predominantly with erlotinib[15-17], but never with masitinib. Interestingly, in four of the cases associated with imatinib, clinical features, time course, histological pattern in the liver biopsy, and a good response to corticosteroids were consistent with an autoimmune DILI[4,5,18-21].

The exact hepatotoxicity mechanisms of tyrosine kinase inhibitors are still unknown, and the pathogenesis of most drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis are complex and not fully understood. At present, limited information is available about the mechanisms by which masitinib and other TK inhibitors induce immune-mediated hepatotoxicity, although a hypersensitivity mechanism has been suggested for imatinib. It has been established that reactive metabolites (RM) are formed during the TK metabolism. These RM in genetically susceptible individuals (within the HLA region on the short arm of chromosome 6, especially those encoding DRB1 alleles) lead to alterations of neighboring host proteins or macromolecules, mainly peptides, and give rise to neoantigens, which are recognized as foreign by the host immune system and able to activate an immune response[4,22,23].

Although in most cases of DILI the patient recovers when the drug is stopped, this is not always the rule. In some cases, hepatic damage continues after treatment with the drug is stopped, as occurred in our patient. One possible explanation for the continuation of liver injury after the administration of the drug has been stopped is that the mechanism involves an autoimmune component, which could continue in the absence of the inciting drug. This mechanism is probably what happened in our case, since the histological pattern was consistent with an autoimmune like histological pattern. Although the existence of autoantibodies was not demonstrated, the excellent response to immunosuppressive treatment, which achieved a biochemical remission of inflammatory activity, suggests that a drug-induced autoimmune-like hepatitis was the type of drug reaction responsible for masitinib hepatotoxicity in our patient[3-5,23-25].

Our patient was taking riluzole (one of the principal criteria for inclusion in this trial). Riluzole is metabolized in the liver via cytochrome P450 (CYP) hydroxylation (principally by CYP1A2) and glucuronidation. Treatment with riluzole has been associated with increases in AST in a small proportion of patients. These increases are usually small and transient and to our knowledge, only 3 cases of icteric toxic hepatitis associated with riluzole have been reported[26,27]. We do not know whether riluzole could increase the risk of hepatotoxicity to masitinib.

These observations mean that it is necessary to investigate the real mechanisms involved in order to explain the hepatotoxicity of these drugs. Meanwhile, taking into account the ongoing clinical trials with masitinib - in our case with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis - and its FDA approval in the treatment of certain types of advanced cancer, it is important that clinicians are aware of this potential complication in practice.

A patient affected with juvenile amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) presented nausea, jaundice and elevated transaminases and bilirubin three months after beginning treatment with masitinib in the context of a clinical trial.

The physical signs suggest a drug-induced liver injury (DILI).

Acute viral hepatitis, DILI, autoimmune hepatitis, chronic active hepatitis, intrahepatic malignancy, infection (cytomegalovirus), autoimmune disorders, extrahepatic biliary obstruction, nonmalignant biliary obstruction, malignant extrahepatic obstruction, sarcoidosis, Dubin-Johnson syndrome, Rotor's syndrome, primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, cholangiocarcinoma, extrahepatic malignancy (pancreas, lymphoma), pancreatitis.

The patient had elevated transaminases (AST 228 IU/L, ALT 250 IU/L). The transaminase values continued to rise to the following maximum values: AST 2221 IU/L, ALT 1166 IU/L, ALP 240 IU/L, and GGT 204 IU/L. Bilirubin rose to 10.47 mg/dL, despite the suspension of masitinib.

Liver ultrasonography showed a normal liver parenchyma and normal biliary tract.

Histological examination showed diffuse parenchymal involvement with marked portal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, with neutrophils, numerous eosinophils and only isolated plasma cells, accompanied by extensive interface hepatitis, occasional bridging necrosis and severe lobular necroinflammatory activity.

Oral prednisone 60 mg daily and oral azathioprine 50 mg daily.

Hepatotoxicity induced by masitinib has been not reported to date.

ALS is a rapidly progressive neurodegenerative disorder predominantly affecting motor neurons, leading to generalized muscle paralysis and death from respiratory failure. Mean survival subsequent to clinical onset is 3-5 years. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled, exploratory phase II/III study of masitinib in patients with ALS is ongoing.

This case report presents the clinical characteristics of autoimmune-like hepatitis induced by masitinib. The authors recommend that clinicians are aware of this potential complication in practice.

The authors have described the first case in the literature of masitinib -induced autoimmune-like hepatitis and the first in a TK inhibitors family in a non-oncological patient - in this case with juvenile onset ALS. The article highlights the clinical characteristics of this DILI/autoimmune-like hepatitis and provides insights into the early diagnosis and therapeutic implications.

P- Reviewer: Chen DY S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Available from: https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/trial/2010-024423-24/ES. Accessed Mar 9, 2015. |

| 2. | Gleeson D, Heneghan MA. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines for management of autoimmune hepatitis. Gut. 2011;60:1611-1629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Czaja AJ. Review article: the management of autoimmune hepatitis beyond consensus guidelines. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:343-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | deLemos AS, Foureau DM, Jacobs C, Ahrens W, Russo MW, Bonkovsky HL. Drug-induced liver injury with autoimmune features. Semin Liver Dis. 2014;34:194-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Casal Moura M, Liberal R, Cardoso H, Horta E Vale AM, Macedo G. Management of autoimmune hepatitis: Focus on pharmacologic treatments beyond corticosteroids. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:410-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Soria JC, Massard C, Magné N, Bader T, Mansfield CD, Blay JY, Bui BN, Moussy A, Hermine O, Armand JP. Phase 1 dose-escalation study of oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor masitinib in advanced and/or metastatic solid cancers. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:2333-2341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mitry E, Hammel P, Deplanque G, Mornex F, Levy P, Seitz JF, Moussy A, Kinet JP, Hermine O, Rougier P. Safety and activity of masitinib in combination with gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66:395-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Le Cesne A, Blay JY, Bui BN, Bouché O, Adenis A, Domont J, Cioffi A, Ray-Coquard I, Lassau N, Bonvalot S. Phase II study of oral masitinib mesilate in imatinib-naïve patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastro-intestinal stromal tumour (GIST). Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1344-1351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Adenis A, Blay JY, Bui-Nguyen B, Bouché O, Bertucci F, Isambert N, Bompas E, Chaigneau L, Domont J, Ray-Coquard I. Masitinib in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) after failure of imatinib: a randomized controlled open-label trial. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1762-1769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dubreuil P, Letard S, Ciufolini M, Gros L, Humbert M, Castéran N, Borge L, Hajem B, Lermet A, Sippl W. Masitinib (AB1010), a potent and selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting KIT. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tebib J, Mariette X, Bourgeois P, Flipo RM, Gaudin P, Le Loët X, Gineste P, Guy L, Mansfield CD, Moussy A. Masitinib in the treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis: results of a multicentre, open-label, dose-ranging, phase 2a study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Paul C, Sans B, Suarez F, Casassus P, Barete S, Lanternier F, Grandpeix-Guyodo C, Dubreuil P, Palmérini F, Mansfield CD. Masitinib for the treatment of systemic and cutaneous mastocytosis with handicap: a phase 2a study. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:921-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Piette F, Belmin J, Vincent H, Schmidt N, Pariel S, Verny M, Marquis C, Mely J, Hugonot-Diener L, Kinet JP. Masitinib as an adjunct therapy for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2011;3:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vermersch P, Benrabah R, Schmidt N, Zéphir H, Clavelou P, Vongsouthi C, Dubreuil P, Moussy A, Hermine O. Masitinib treatment in patients with progressive multiple sclerosis: a randomized pilot study. BMC Neurol. 2012;12:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ramanarayanan J, Scarpace SL. Acute drug induced hepatitis due to erlotinib. JOP. 2007;8:39-43. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Lai YC, Lin PC, Lai JI, Hsu SY, Kuo LC, Chang SC, Wang WS. Successful treatment of erlotinib-induced acute hepatitis and acute interstitial pneumonitis with high-dose corticosteroid: a case report and literature review. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;49:461-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Leise MD, Poterucha JJ, Talwalkar JA. Drug-induced liver injury. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:95-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dhalluin-Venier V, Besson C, Dimet S, Thirot-Bibault A, Tchernia G, Buffet C. Imatinib mesylate-induced acute hepatitis with autoimmune features. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:1235-1237. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Al Sobhi E, Zahrani Z, Zevallos E, Zuraiki A. Imatinib-induced immune hepatitis: case report and literature review. Hematology. 2007;12:49-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Charier F, Chagneau-Derrode C, Levillain P, Guilhot F, Silvain C. [Glivec induced autoimmune hepatitis]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33:982-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Aliberti S, Grignani G, Allione P, Fizzotti M, Galatola G, Pisacane A, Aglietta M. An acute hepatitis resembling autoimmune hepatitis occurring during imatinib therapy in a gastrointestinal stromal tumor patient. Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32:640-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liberal R, Grant CR, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Autoimmune hepatitis: a comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2013;41:126-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Teo YL, Ho HK, Chan A. Formation of reactive metabolites and management of tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced hepatotoxicity: a literature review. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2015;11:231-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Uetrecht J. Immunoallergic drug-induced liver injury in humans. Semin Liver Dis. 2009;29:383-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Björnsson E, Talwalkar J, Treeprasertsuk S, Kamath PS, Takahashi N, Sanderson S, Neuhauser M, Lindor K. Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: clinical characteristics and prognosis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2040-2048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |