Published online Sep 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i34.10049

Peer-review started: March 5, 2015

First decision: April 24, 2015

Revised: May 9, 2015

Accepted: July 3, 2015

Article in press: July 3, 2015

Published online: September 14, 2015

Processing time: 194 Days and 23.2 Hours

Patients with cancer are at high risk for thrombotic events, which are known collectively as Trousseau’s syndrome. Herein, we report a 66-year-old male patient who was diagnosed with terminal stage gastric cancer and liver metastasis and who had an initial clinical presentation of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Acute ischemia of the left lower leg that resulted in gangrenous changes occurred during admission. Subsequent angiography of the left lower limb was then performed. This procedure revealed arterial thrombosis of the left common iliac artery with extension to the external iliac artery, the left common iliac artery, the posterior tibial artery, and the peroneal artery, which were occluded by thrombi. Aspiration of the thrombi demonstrated that these were not tumor thrombi. The interesting aspect of our case was that the disease it presented as arterial thrombotic events, which may correlate with gastric adenocarcinoma. In summary, we suggested that the unexplained thrombotic events might be one of the initial presentations of occult malignancy and that thromboprophylaxis should always be considered.

Core tip: Patients with cancer are at high risk for thrombotic events, which are collectively known as Trousseau’s syndrome. This case report reviews arterial thrombotic events that occurred in a patient with gastric cancer. An unexplained thrombotic event might be one of the initial presentations of occult malignancy, and thus, thromboprophylaxis should always be considered.

- Citation: Chien TL, Rau KM, Chung WJ, Tai WC, Wang SH, Chiu YC, Wu KL, Chou YP, Wu CC, Chen YH, Chuah SK, Gastric Cancer Team. Trousseau’s syndrome in a patient with advanced stage gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(34): 10049-10053

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i34/10049.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i34.10049

Cancer patients are at high risk for thrombosis because they are prone to hypercoagulopathy. Trousseau’s syndrome is defined as the occurrence of any thrombotic event in a given cancer patient[1]. The risk of thrombosis depends on the tumor type, stage, extent of the cancer, obesity, immobilization status of the patient, history of prior thrombotic events, family history and type of treatment used. Trousseau’s syndrome ranges from the “occurrence of thrombophlebitis migrans with visceral cancer” and “spontaneous recurrent or migratory venous thromboses and/or arterial emboli caused by nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis” to simple “carcinoma-induced coagulopathy” and “hypercoagulability syndrome”[2]. Herein we report a rare case of Trousseau’s syndrome, which presented as acute ischemic limb due to occlusion of the left common iliac artery to the external iliac artery.

A 66-year-old male with a history of peptic ulcer and gouty arthritis was brought to the emergency room because of tarry stool passage for 4 d and a fever of up to 38.2 °C, which lasted for 2 d. A physical examination revealed an acutely unhealthy-looking, conscious man with pale conjunctiva. His abdomen was soft, tympanic, and mildly tender, and the bowel sounds were hyperactive. The liver and spleen were not palpable, and no abdominal mass was detected. His extremities were non-edematous and had symmetrical pulses. His laboratory data on admission were as follows - white blood cell count: 11500/μL (3500-11000/μL), hemoglobin: 9.2 g/dL (12-16 g/dL), hematocrit: 27% (36%-46%), mean corpuscular volume: 96.8 fL (80-100 fL), platelet count: 180 × 103/μL (150-400 × 103/μL), total bilirubin: 0.3 mg/dL (0.2-1.4 mg/dL), aspartate transaminase: 37 IU/L (0-37 IU/L), alanine transaminase: 48 IU/L (0-40 IU/L), alkaline phosphatase: 165 IU/L (28-94 IU/L), creatinine 0.94 mg/dL (0.64-1 mg/dL), sodium: 136 mmol/L (134-148 mmol/L), potassium: 3.0 mmol/L (3.0-4.8 mmol/L), CA-199 > 50000 U/mL (< 37 U/mL), carcinoembryonic antigen 45.46 ng/mL (< 5 ng/mL), alpha fetoprotein 15.6 ng/mL (< 20 ng/mL). The laboratory data on the 12th day after admission were as follows - PT 12.5 s (8-12 s), international normalized ratio 1.18, activated partial thromboplastin time 28.2 s (24.6-33.8 s), D-dimer > 35 mg/L FEU (< 0.5 mg/L).

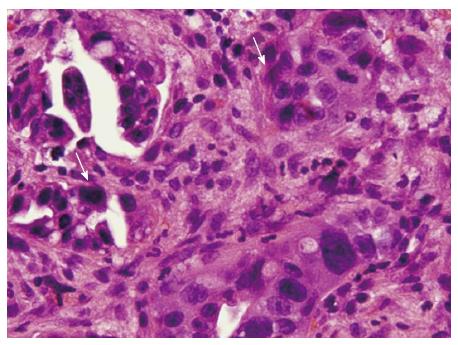

The patient then received an abdominal ultrasound, which revealed multiple hypoechoic nodules over both lobes of the livers; adenocarcinoma was confirmed by subsequent echo-guided fine needle aspiration of the liver tumor. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a 2.5-cm penetrating ulcer on the side of the lesser curvature of the antrum (Figure 1). A pathologic analysis confirmed the diagnosis of a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma that was negative for HER-2/neu (Figure 2). Abdominal computed tomography with contrast revealed multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the perigastric, gastrohepatic and portacaval ligaments as well as numerous nodules in both lobes of the liver.

After admission, an empiric antibiotic regimen of 1st generation cephalosporin was prescribed to control right foot cellulitis. A PORT-A-catheter was implanted prior to chemotherapy administration. At On the same day, the patient complained of numbness in the left foot together with cyanosis of the left toes and coldness of the left lower limb. Peripheral pulsations were weak for the left femoral and popliteal arteries while pulses of the dorsalis pedis artery were not detected at all.

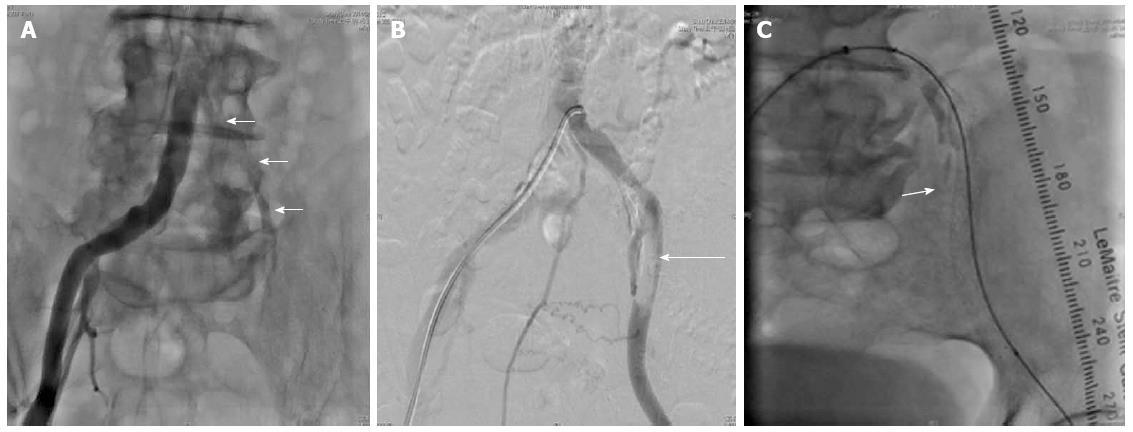

A duplex color scan of the lower extremities revealed segmentally mild atherosclerosis distal to the left iliac artery and an abnormal arterial duplex waveform from the left femoral segment to the tibial segment. The condition worsened after the development of gangrenous changes of the left toes. Clopidogrel, cilostazol and heparin were prescribed. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed adequate left ventricle and right ventricle performance, trivial mitral regurgitation and tricuspid regurgitation. A percutaneous transluminal angiography (PTA) was performed on the 12th day after admission and revealed a long diffuse stenosis of the left common iliac artery that occupied 79% of the lumen (Figure 3A); angiography also revealed the localization of 7-mm × 6-mm thrombi in the left external iliac artery and in the left internal iliac artery (Figure 3B).

A bare metallic stent was placed from the left common iliac artery to the external iliac artery. Thrombus aspiration was performed in the left anterior tibial artery, the left posterior tibial artery, and the left peroneal artery followed by balloon angioplasty of the peroneal artery under the impression of “Trousseau’s syndrome” (Figure 3C).

Left foot cyanosis and pain improved dramatically after the PTA but recurred rapidly despite the prescription of a heparin drip. PTA was performed again on the 23rd day after admission and revealed local thrombi in the left anterior tibial artery and the dorsalis pedis artery as well as total thrombosis of the left peroneal artery and the posterior tibial artery. The patient’s condition deteriorated upon commencement of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, liver failure, and renal failure, and despite his critical condition, he was discharged against the advice of physicians.

This case report was approved by both the Institutional Review Board and the Ethics Committee of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan (IRB104-0636B). The Ethics Committee waived the requirement for informed consent for this study.

Armand Trousseau first described that unexpected or migratory thrombophlebitis could be a warning sign of an occult visceral malignancy[1]. The term “Trousseau’s syndrome” has been extended to include chronic disseminated intravascular coagulopathy associated with microangiopathy, verrucous endocarditis, and arterial emboli in patients with cancer. These events often occur in conjunction with mucin-positive carcinomas. The term “Trousseau’s syndrome” has now been ascribed to various clinical situations that range from these classic descriptions to any type of coagulopathy that occurs in the setting of any kind of malignancy[3]. These include arterial and venous thrombosis, non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE), thrombotic microangiopathy and veno-occlusive disease[2].

The pathogenesis of hemostatic disorders in cancer is complex and reflects the interaction of different mechanisms, including activation of the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems, perturbation of the vascular endothelium, and generalized activation of cellular mechanisms for the promotion of clotting on the surface of circulating monocytes and platelets. Nonspecific factors such as the generation of acute phase reactants and necrosis (associated with the host inflammatory response), aberrant protein metabolism (e.g., generation of paraproteins) and hemodynamic compromise (stasis), can all contribute to the activation of blood coagulation in cancer patients. However, tumor-specific clot-promoting mechanisms are most often implicated in the pathogenesis of the hypercoagulability that is characteristic of patients with cancer[3].

In one prospective study of 2085 Asian patients with gastric cancer, the 2-year cumulative incidence of venous thromboembolism after the diagnosis of gastric cancer was 3.8%[3]. Cancer patients have a several-fold increased risk of venous thrombosis compared with the general population or patients without cancer. It has been consistently estimated that 20% to 30% of all initial venous thromboembolic events are cancer-related[4].

Our patient was suspected to have deep vein thrombosis in the lower left leg. Swelling, pain and erythema of the left calf area were noted. These symptoms are nonspecific findings, and thus required further investigation. However, the patient’s condition was critical, and family members requested that the patient be discharged at that time against the advice of physicians.

In one population-based study, patients with hematological malignancies experienced the highest risk of vein thrombosis embolism (OR = 28; 95%CI: 4.0-199.7), followed by lung (OR = 22.2; 95%CI: 3.6-136.1), and gastrointestinal cancers (OR = 20.3; 95%CI: 4.9-83.0). The highest risk for VTE is observed during the initial period following the diagnosis of cancer. The risk of VTE was greatest in the first 3 mo after the diagnosis of cancer (OR = 53.5; 95%CI: 8.6-334.3)[5]. In the American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines 9th edition, high-risk patients for VTE are identified by a scoring system (Padua prediction score risk assessment model). Risk factors in this scoring system include active cancer, previous VTE, reduced mobility, a previously diagnosed thrombophilic condition, recent trauma and/or surgery, advanced age, heart and/or respiratory failure, acute myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke, acute infection and/or rheumatologic disorder, obesity, and ongoing hormonal treatment.

A high risk of VTE is defined by a cumulative score greater than or equal to 4 points. Active cancer receives a score of 3 points. In a prospective observational study of 1180 medical inpatients, 60.3% of patients were low-risk and 39.7% were high-risk. Among the patients who did not receive prophylaxis, VTE occurred in 11.0% of the high-risk patients vs 0.3% of the low-risk patients (HR = 32.0; 95%CI: 4.1-251.0). Among the high-risk patients, the risk of deep vein thrombosis, nonfatal pulmonary embolism and fatal PE was 6.7%, 3.9%, and 0.4%, respectively[6].

According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update (2013), acutely ill hospitalized patients at an increased risk of thrombosis should receive anticoagulant prophylaxis (Evidence: strong. Recommendation type, strength: evidence-based, strong). LMWH is preferred over UFH for the initial 5 to 10 d of anticoagulation for patients with cancer and newly diagnosed VTE who do not have severe renal impairment (defined as creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min). For outpatients with cancer who have no additional risk factors for VTE, thromboprophylaxis was not suggested (Evidence: moderate. Recommendation type, strength: evidence-based, strong)[7].

In summary, we suggested that unexplained thrombotic events might be one of the initial presentations of occult malignancy and that thromboprophylaxis should always be considered. Out of the population of patients with cancer, we need to identify patients who are at a higher risk for thrombosis and prescribe prophylactic anticoagulant therapy for these high-risk patients.

A 66-year-old male with a history of peptic ulcer and gouty arthritis was brought to the emergency room because of tarry stool passage for 4 d and a fever of up to 38.2 °C, which lasted for 2 d.

The patient experienced numbness of the left foot together with cyanosis of the left toes and coldness of the left lower limb. Peripheral pulsations were weak for the left femoral and popliteal arteries while pulses of the dorsalis pedis artery were not detected at all.

Percutaneous transluminal angiography was performed on the 12th day after admission; this revealed a long diffuse stenosis of the left common iliac artery that occupied 79% of the lumen and localization of 7 × 6-mm thrombi in the left external iliac artery and in the left internal iliac artery.

A bare metallic stent was placed from the left common iliac artery to the external iliac artery. Thrombus aspirations were performed in the left anterior tibial artery, the left posterior tibial artery, and the left peroneal artery followed by balloon angioplasty of the peroneal artery.

Unexplained thrombotic events might be one of the initial presentations of occult malignancy, and thus thromboprophylaxis should always be considered.

This case report demonstrates very interesting presentation of gastric cancer, and well written.

P- Reviewer: Takeda H S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Varki A. Trousseau’s syndrome: multiple definitions and multiple mechanisms. Blood. 2007;110:1723-1729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 512] [Cited by in RCA: 556] [Article Influence: 30.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Falanga A, Marchetti M, Vignoli A. Coagulation and cancer: biological and clinical aspects. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:223-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 296] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Article Influence: 29.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lee KW, Bang SM, Kim S, Lee HJ, Shin DY, Koh Y, Lee YG, Cha Y, Kim YJ, Kim JH. The incidence, risk factors and prognostic implications of venous thromboembolism in patients with gastric cancer. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:540-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Timp JF, Braekkan SK, Versteeg HH, Cannegieter SC. Epidemiology of cancer-associated venous thrombosis. Blood. 2013;122:1712-1723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 637] [Cited by in RCA: 843] [Article Influence: 70.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Blom JW, Doggen CJ, Osanto S, Rosendaal FR. Malignancies, prothrombotic mutations, and the risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA. 2005;293:715-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1353] [Cited by in RCA: 1460] [Article Influence: 73.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, Cushman M, Dentali F, Akl EA, Cook DJ, Balekian AA, Klein RC, Le H. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e195S-e226S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1121] [Cited by in RCA: 1131] [Article Influence: 87.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lyman GH, Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Lee AY, Arcelus JI, Balaban EP, Clarke JM, Flowers CR, Francis CW, Gates LE. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2189-2204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 602] [Cited by in RCA: 589] [Article Influence: 49.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |