Published online Jul 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i27.8452

Peer-review started: October 29, 2014

First decision: November 14, 2014

Revised: December 2, 2014

Accepted: January 16, 2015

Article in press: January 16, 2015

Published online: July 21, 2015

Processing time: 64 Days and 1.6 Hours

Pancreatic metastases are uncommon. They have been reported in lung cancer, gastrointestinal malignancies, breast cancer, renal cell carcinoma, melanoma, lymphoma and sarcoma, and usually have solid morphology. Cystic metastasis to the pancreas is even more rare with few case reports in the literature. However, with the increasing use of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging as well as endoscopic ultrasound, more such lesions may be detected. Metastasis to the pancreas from osteosarcoma is highly unusual, but can be seen with the increasing survival of patients with osteosarcoma. We present an extremely rare case of a predominantly cystic lesion of the pancreas, which was diagnosed as metastasis from osteosarcoma. The pathophysiology of the cystic component of the metastasis of osteosarcoma is unknown. Cystic necrotic degeneration of the solid metastasis or pancreatitis secondary to the metastasis with development of associated fluid collection can be considered. Metastasis should remain a differential consideration even for primarily cystic lesions of the pancreas.

Core tip: Cystic pancreatic lesions are more commonly recognized and diagnosed with developing imaging technologies. Metastasis to the pancreas from osteosarcoma is unusual, but has been reported in terms of solid pancreatic masses. This case report shows that metastasis should remain in the differential diagnosis even for primarily cystic pancreatic lesions.

- Citation: Akpinar B, Obuch J, Fukami N, Pokharel SS. Unusual presentation of a pancreatic cyst resulting from osteosarcoma metastasis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(27): 8452-8457

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i27/8452.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i27.8452

Pancreatic metastasis from osteosarcoma is an uncommon condition, seen in the very late stages of the disease. Metastatic lesions to the pancreas are usually solid masses. We present a case of cystic pancreatic metastasis in a patient with a history of osteogenic sarcoma with known metastasis involving the left lower lung lobe.

A 53-year-old female was referred to our hospital with abdominal pain, fullness and early satiety. She had been diagnosed with high-grade osteoblastic osteogenic sarcoma, giant cell rich, of her left distal femur four years earlier. She was treated with resection of the tumor and multiple chemotherapy agents. She developed several pulmonary metastases, with attempts at resection one year prior to the presentation.

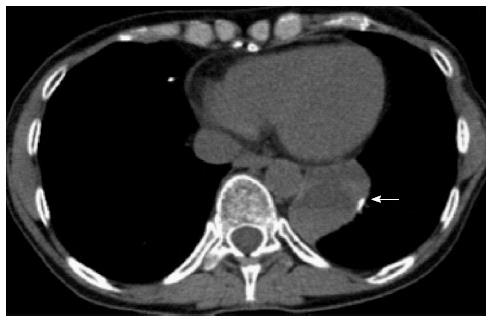

Two months prior to presentation she underwent a left video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery with resection of the lateral and posterior segment of the left lower lung (Figure 1). The final pathology from that surgery showed metastatic osteogenic sarcoma, giant cell rich, 6.5 cm in greatest dimension, invading the parietal pleura, focally involving the inked surgical margins (inferior pulmonary ligament).

She had been recovering well from that surgical intervention when she was hospitalized with worsening abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and early satiety at an outside hospital. She was evaluated with computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis, which showed a very large complex cystic mass anterior to the pancreas measuring 19 cm × 6 cm. This appeared significantly enlarged from a month prior where an outside CT at that time showed an 11 cm × 3 cm cystic pancreatic mass in the same location. The cystic mass contained enhancing soft tissue components posteriorly as well as solid components that appeared to have significantly enlarged.

She was sent to interventional radiology for drainage of the cystic lesion where approximately 1400 cc’s of fluid were obtained resulting in significant improvement of her symptoms. Cytologic analysis of the fluid at that time was negative for malignancy. Her pain was controlled with narcotics as needed, with plans for repeat ultrasound in two weeks for evaluation of fluid reaccumulation. Her abdominal symptoms initially were controlled, but returned several days later prompting her to present to our hospital.

On initial exam at our hospital, she appeared emaciated and weak with abdominal fullness in the epigastric area without rebound appreciated on palpation. Review of her history revealed no personal history of pancreatitis or excessive alcohol use. Laboratory data showed an anemia with a hemoglobin of 8.1 g/dL, hyponatremia and hypokalemia with values of 130 mmol/L and 2.8 mmol/L respectively, and mildly elevated lipase measuring 185 U/L. Her serum CA 19-9 was elevated at 39.0 U/mL.

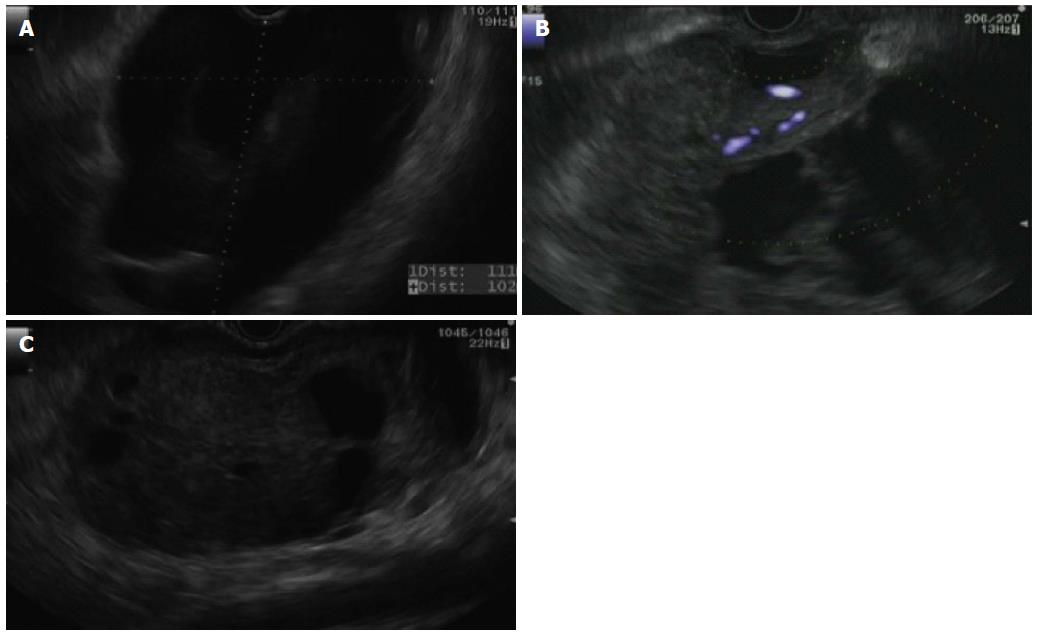

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was performed in our hospital, where extrinsic compression of the stomach was found along the posterior wall. An oval mass with both solid and cystic components was identified involving the genu, body, and tail of the pancreas. Normal pancreatic tissue was not well seen due to the size of the lesion with one large cystic component in the body and genu extending to the liver hilum (Figure 2A). The mass measured 11 cm × 10 cm in size with blood flow observed within the solid component (Figure 2B). Diagnostic and therapeutic needle aspiration was performed, revealing a turbid, brown, thin liquid suggestive of old blood. Samples were sent for cell count and differential, amylase, cytology, microbiology and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). A total of 1000 cc’s was aspirated from the cystic component, significantly reducing the cystic collection (Figure 2C). At the conclusion of the EUS, no overtly hypoechoic areas suspicious for malignancy were identified, with an initial differential diagnosis including solid pseudopapillary tumor vs serous cystadenoma with large cystic component. A pseudocyst was thought to be less likely due to the lack of pancreatitis by history.

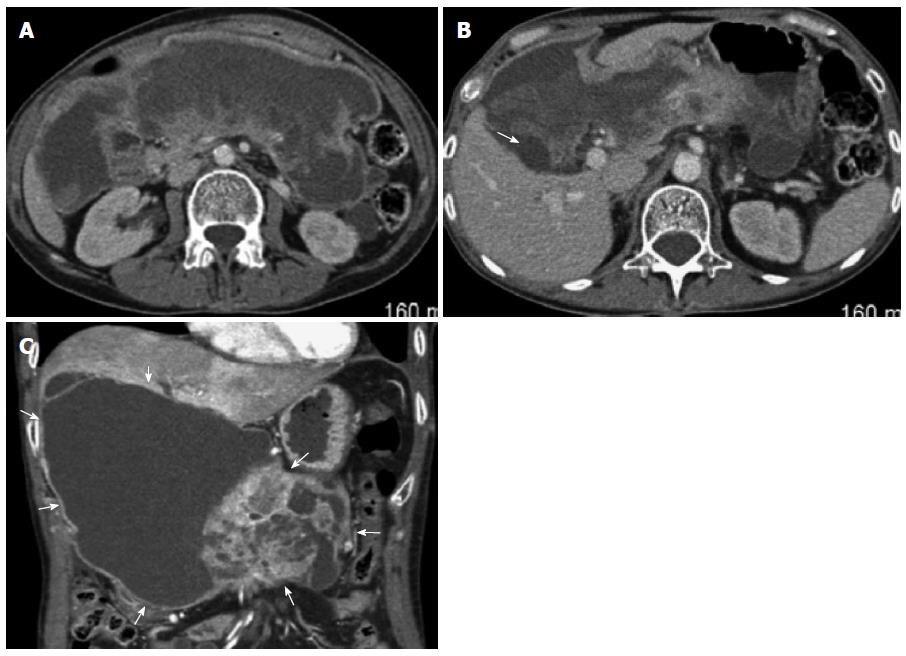

CT of the abdomen with and without contrast agent was performed after her EUS, showing a large multiloculated cystic mass extending from the hepatic hilum into the pelvis replacing a majority of the pancreatic parenchyma in the neck, body, and tail (Figure 3). The edges of the mass appeared to abut the liver at the gallbladder fossa as well as the right and left lobes with portions of the duodenum also encased by the mass. In addition, the distal portion of the stomach appeared compressed by the mass with resulting dilation in the fundus. The head and distal tail of the pancreas appeared normal other than possible minimal ductal dilation in the distal tail, and the bile ducts appeared non-dilated (Figure 3).

Fluid analysis from her EUS guided fine needle aspiration had a cell count with 3891 × 106/L nucleated cells and 23176 × 106/L red blood cells. Cyst fluid CEA was 2.4 ng/mL and amylase was 18160 U/L suggesting against serous cystadenoma, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, solid pseudopapillary neoplasm, or mucinous cystadenoma. Cytology results confirmed malignant cells with numerous multinucleated giant cells, consistent with osteosarcoma metastasis to the pancreas. The tumor was highly cellular and showed frequent mitotic activity (17 mitoses per 10 high powered fields). When compared to the patient’s prior lung resection for metastatic osteosarcoma, similar morphology was observed. While the differential for such findings also includes undifferentiated pancreatic carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells (which are negative for keratin markers 50% of the time), in light of the patient’s oncologic history, this pancreatic cystic tumor was deemed to be an osteosarcoma metastasis.

Cystic pancreatic lesions may be classified into inflammatory fluid collections, non-neoplastic cysts, cystic neoplasms, and cystic degeneration of solid tumors (Table 1). Inflammatory fluid collections, which are not true epithelial cysts, can be subclassified into acute peripancreatic fluid collections, pseudocysts, acute necrotic collections, and walled-off pancreatic necrosis, according to the revised Atlanta classification[1]. Non-neoplastic pancreatic cysts have no malignant potential and include true cysts (benign epithelial cysts), retention cysts, mucinous non-neoplastic cysts[2] and lymphoepithelial cysts[3]. Pancreatic cystic neoplasms include serous cystic tumor, most of which are serous cystadenomas (SCA), mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN), intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) and solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPEN)[4]. MCNs and IPMNs are premalignant or malignant. SPENs are thought to have low malignant potential and SCAs have low or no malignant potential[5]. Necrotic degeneration of solid tumors can be seen with neuroendocrine tumors, ductal adenocarcinomas, and acinar cell carcinoma. Follow-up and treatment options are based on the diagnostic criteria such as imaging findings and pathology results of biopsy specimens[6].

| Cystic pancreatic lesions |

| Inflammatory fluid collections |

| Acute peripancreatic fluid collections |

| Pseudocysts |

| Acute necrotic collections |

| Walled-off pancreatic necrosis |

| Non-neoplastic cysts |

| True cysts (benign epithelial cysts) |

| Retention cysts |

| Mucinous non-neoplastic cysts |

| Lymphoepithelial cysts |

| Cystic neoplasms |

| Serous cystadenoma |

| Mucinous cystic neoplasm |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm |

| Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm |

| Cystic degeneration of solid tumors |

| Neuroendocrine tumors |

| Ductal adenocarcinoma |

| Acinar cell carcinoma |

Pancreatic lesions are increasingly diagnosed with the use of radiologic examinations such as ultrasound, CT, magnetic resonance and lately EUS, which carries the benefit of needle aspiration via endosonographic guided biopsy. Pancreatic metastases are uncommon, but have been reported in malignancies originating in the lung, gastrointestinal tract, breast, kidneys, as well as in melanoma, lymphoma and sarcoma. Their incidence ranges from 1.6% to 12% at autopsy of cancer patients depending on the primary tumor location[7,8].

There are case reports of cystic metastasis to the pancreas from pulmonary carcinoma[9], as well as Merkel cell carcinoma, which is a primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin[10].

Regarding osteosarcoma, it most commonly metastasizes to the lungs, followed by skeleton, pleura, heart and lymph nodes. Soft tissue or abdominal organ metastases are extremely rare but can be seen in late stages[11,12]. Calcification or ossification can be seen within the lesion[13]. There are few reports of pancreatic metastases from osteosarcoma in the literature. However, most of these are solid metastases[14-18]. There is a case report of a cystic-solid mass on the head of the pancreas with the diagnosis of metastatic osteosarcoma in an 18 year old, which was confirmed with endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of necrotic debris[19]. The pathophysiology of the cystic component of the metastasis of osteosarcoma is unknown. Cystic, necrotic degeneration of the solid metastasis or pancreatitis secondary to the metastasis with development of associated fluid collection can be considered. Our current case presentation is even more unusual with a predominantly cystic osteosarcoma metastasis to the pancreas without evidence of calcification.

Pancreatic metastases from osteosarcoma, although rare, may be seen more frequently with the continued improvement in treatment and increasing survival of patients with osteosarcoma. Furthermore, metastasis should remain a differential consideration even for a mostly cystic pancreatic mass in a patient with a known primary malignancy.

A 53-years-old female with a history of osteosarcoma metastasize to lung presented with abdominal pain, fullness and early satiety.

Abdominal fullness in the epigastric area without rebound on palpation.

Abdominal mass, enteric obstruction.

HGB 8.1 g/dL, Na 130 mmol/L, K 2.8 mmol/L, serum lipase 185 U/L, serum CA 19-9 39.0 U/mL.

Endoscopic ultrasound, computed tomography scan showed large multiloculated cystic mass (11 cm × 10 cm) involving the genu, body, and tail of the pancreas, extending from the hepatic hilum into the pelvis.

Diagnostic needle aspiration cytology revealed malignant cells with numerous multinucleated giant cells, consistent with osteosarcoma metastasis to the pancreas. The tumor was highly cellular and showed frequent mitotic activity (17 mitoses per 10 high powered fields).

Therapeutic needle aspiration was performed to control the abdominal symptoms.

There are few reports of pancreatic metastases from osteosarcoma in the literature. However, most of these are solid metastases. The authors have found a case report of a cystic-solid mass on the head of the pancreas, which was an osteosarcoma metastasis, also diagnosed with endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of necrotic debris.

Cystic osteosarcoma metastasis to the pancreas is an unusual presentation of a metastatic lesion of pancreas, which can be seen with the increasing survival of patients with osteosarcoma.

Pancreatic metastases from osteosarcoma, although rare, may be seen more frequently with the continued improvement in treatment and increasing survival of patients with osteosarcoma. Furthermore, metastasis should remain a differential consideration even if a cystic component is present within a pancreatic mass in a patient with known primary malignancy.

This is a straight forward case report of a metastatic bone tumor to the pancreas presenting as a cystic pancreatic mass lesion. The case raises several interesting points and the images are adequate.

P- Reviewer: Mel Wilcox C S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4328] [Article Influence: 360.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 2. | Cao W, Adley BP, Liao J, Lin X, Talamonti M, Bentrem DJ, Rao SM, Yang GY. Mucinous nonneoplastic cyst of the pancreas: apomucin phenotype distinguishes this entity from intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:513-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ramsden KL, Newman J. Lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas. Histopathology. 1991;18:267-268. [PubMed] |

| 4. | World Health Organization Classification of Tumours; Aaltonen LA, Hamilton SR (Eds). Tumours of the exocrine pancreas. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC Press 2000; 219-253. |

| 5. | Lee LS. Incidental Cystic Lesions in the Pancreas: Resect? EUS? Follow? Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2014;12:333-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Enestvedt BK, Ahmad N. To cease or ‘de-cyst’? The evaluation and management of pancreatic cystic lesions. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15:348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Adsay NV, Andea A, Basturk O, Kilinc N, Nassar H, Cheng JD. Secondary tumors of the pancreas: an analysis of a surgical and autopsy database and review of the literature. Virchows Arch. 2004;444:527-535. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Washington K, McDonagh D. Secondary tumors of the gastrointestinal tract: surgical pathologic findings and comparison with autopsy survey. Mod Pathol. 1995;8:427-433. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Ramirez Plaza CP, Suàrez Muñoz MA, Santoyo Santoyo J, Perez Lara FJ, Iaria M, Raso L, Fernandez Aguilar JL, Jimenez Hernandez M, Arrabal Sànchez R, Bondia Navarro JA. [Pancreatic cystic metastasis from pulmonary carcinoma. Report of a case]. Ann Ital Chir. 2001;72:95-99. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Bachmeyer C, Alovor G, Chatelain D, Khuoy L, Turc Y, Danon O, Laurette F, Cazier A, N’Guyen V. Cystic metastasis of the pancreas indicating relapse of Merkel cell carcinoma. Pancreas. 2002;24:103-105. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Wolf R, Wolf RF, Hoekstra HJ. Recurrent, multiple, calcified soft tissue metastases from osteogenic sarcoma without pulmonary involvement. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28:710-713. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Kim SJ, Choi JA, Lee SH, Choi JY, Hong SH, Chung HW, Kang HS. Imaging findings of extrapulmonary metastases of osteosarcoma. Clin Imaging. 2004;28:291-300. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Avcu S, Akdeniz H, Arslan H, Toprak N, Unal O. A case of primary vertebral osteosarcoma metastasizing to pancreas. JOP. 2009;10:438-440. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Bertucci F, Araujo J, Giovannini M. Pancreatic metastasis from osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma: literature review. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:4-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mulligan ME, Fellows DW, Mullen SE. Pancreatic metastasis from Ewing’s sarcoma. Clin Imaging. 1997;21:23-26. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Obuz F, Kovanlikaya A, Olgun N, Sarialioğlu F, Ozer E. MR imaging of pancreatic metastasis from extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma. Pancreas. 2000;20:102-104. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Aarvold A, Bann S, Giblin V, Wotherspoon A, Mudan SS. Osteosarcoma metastasising to the duodenum and pancreas. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:542-544. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Lasithiotakis K, Petrakis I, Georgiadis G, Paraskakis S, Chalkiadakis G, Chrysos E. Pancreatic resection for metastasis to the pancreas from colon and lung cancer, and osteosarcoma. JOP. 2010;11:593-596. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Jin P, Wang W, Su H, Sheng JQ. Osteosarcoma metastasizing to pancreas confirmed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E109-E110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |