Published online Jul 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i27.8408

Peer-review started: January 25, 2015

First decision: March 10, 2015

Revised: March 30, 2015

Accepted: May 21, 2015

Article in press: May 21, 2015

Published online: July 21, 2015

Processing time: 179 Days and 3 Hours

AIM: To investigate the characteristics of gastric cancer and gastric mucosa in a Mongolian population by comparison with a Japanese population.

METHODS: A total of 484 Mongolian patients with gastric cancer were enrolled to study gastric cancer characteristics in Mongolians. In addition, a total of 208 Mongolian and 3205 Japanese consecutive outpatients who underwent endoscopy, had abdominal complaints, no history of gastric operation or Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment, and no use of gastric secretion inhibitors such as histamine H2-receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors were enrolled. This study was conducted with the approval of the ethics committees of all hospitals. The triple-site biopsy method was used for the histologic diagnosis of gastritis and H. pylori infection in all Mongolian and Japanese cases. The infection rate of H. pylori and the status of gastric mucosa in H. pylori-infected patients were compared between Mongolian and Japanese subjects. Age (± 5 years), sex, and endoscopic diagnosis were matched between the two countries.

RESULTS: Approximately 70% of Mongolian patients with gastric cancer were 50-79 years of age, and approximately half of the cancers were located in the upper part of the stomach. Histologically, 65.7% of early cancers exhibited differentiated adenocarcinoma, whereas 73.9% of advanced cancers displayed undifferentiated adenocarcinoma. The infection rate of H. pylori was higher in Mongolian than Japanese patients (75.9% vs 48.3%, P < 0.0001). When stratified by age, the prevalence was highest among young patients, and tended to decrease in patients aged 50 years or older. The anti-East-Asian CagA-specific antibody was negative in 99.4% of H. pylori-positive Mongolian patients. Chronic inflammation, neutrophil activity, glandular atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia scores were significantly lower in Mongolian compared to Japanese H. pylori-positive patients (P < 0.0001), with the exception of the intestinal metaplasia score of specimen from the greater curvature of the upper body. The type of gastritis changed from antrum-predominant gastritis to corpus-predominant gastritis with age in both populations.

CONCLUSION: Gastric cancer was located in the upper part of the stomach in half of the Mongolian patients; Mongolian patients were infected with non-East-Asian-type H. pylori.

Core tip: Characteristics of gastric cancer and gastric mucosa in Mongolian patients were observed; approximately half of the cancers were located in the upper part of the stomach. The infection rate of Helicobacter pylori was higher in Mongolian compared to Japanese patients (75.9% vs 48.3%, P < 0.0001). Mongolian patients were infected with non-East-Asian-type H. pylori strains. Atrophic and intestinal metaplasia scores were lower in H. pylori-infected Mongolian patients compared to Japanese patients (P < 0.0001). The type of gastritis changed from antrum-predominant gastritis to corpus-predominant gastritis with age in both populations.

-

Citation: Matsuhisa T, Yamaoka Y, Uchida T, Duger D, Adiyasuren B, Khasag O, Tegshee T, Tsogt-Ochir B. Gastric mucosa in Mongolian and Japanese patients with gastric cancer and

Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(27): 8408-8417 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i27/8408.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i27.8408

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infections cause not only peptic ulcer disease, but also gastric cancer[1,2]. Among H. pylori strains, there is a Western-type and an East-Asian-type; the East-Asian-type strain greatly influences the development of atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer. Mongolia, South Korea, and Japan are located in Eastern Asia and have the highest incidence of gastric cancer in the world [age-standardized incidence rates (ASR): 47.4 cases per 100000 males, 62.3 cases per 100000 males, and 45.8 cases per 100000 males, respectively][3]. In spite of the high prevalence of H. pylori infection in Bangladeshi[4,5], Thai[6], and Indian populations, the incidence of gastric cancer in these countries is extremely low. These trends have been denoted as Asian enigmas[7] or the Asian Paradox[8]. In this report, the characteristics of gastric cancer, H. pylori infection, and gastric mucosa in Mongolian and Japanese patients were observed and compared.

Between January 2011 and December 2013, 484 consecutive gastric cancer patients (mean age: 60.5 years, range, 26-93 years; male-to-female ratio of 1:0.51) in the Department of Endoscopy of Ulaanbaatar Songdo Hospital (Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia) were enrolled to study the characteristics of gastric cancer in Mongolian patients.

In addition, we performed endoscopy on 208 consecutive outpatients (mean age: 41.6 years, range, 17-79 years; male-to-female ratio of 1:1.89) at the Department of Gastroenterology, Health Sciences University of Mongolia, the Department of Endoscopy, Ulaanbaatar Songdo Hospital, and the Department of Gastroenterology, Third Central State Hospital in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia in November 2013. The data were compared with our independent endoscopy survey of 3205 consecutive outpatients (mean age: 55.1 years, range, 14-93 years male-to-female ratio of 1:0.73) at Nippon Medical School between January 2008 and March 2014 in Tokyo, Japan. All patients in both countries had abdominal complaints, no history of gastric operation or H. pylori-eradication treatment, and no use of gastric secretion inhibitors such as histamine H2-receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors.

This study was conducted with the approval of the ethics committees of all hospitals. Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all patients except minors, whose consent was obtained from the guardian. All endoscopy procedures in Mongolian patients were performed by T Matsuhisa and Y Yamaoka using the same criteria used for the Japanese patients. All endoscopy procedures in Japanese patients were performed by T Matsuhisa.

The 3rd English edition of the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma was used for histologic classification and to describe the location of the gastric cancer: upper (U), middle (M), and lower (L)[9]. Cancer lesions involved in more than two regions were excluded. Among gastric cardia cancers, cancers in the stomach < 2 cm distal to the esophagogastric junction were included in the cases of the U region. Nishi’s criterion (in Japanese) was used for the definition of gastric cardia cancer (esophagogastric cancer). According to this criterion, the tumor center must be located in the stomach or esophagus within 2 cm of the esophagogastric junction, irrespective of histology. This criterion is also included in the 3rd English edition of Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma[9]. The locations of gastric cancers were diagnosed by Mongolian doctors (T Tegshee and B Adiyasuren).

Cancer limited to mucosa or submucosa was defined as early gastric cancer, regardless of the presence or absence of lymph node metastases[9]. Advanced gastric cancer was defined as cancer that had infiltrated a deeper layer than the muscularis propria[9].

Papillary adenocarcinoma, well-differentiated type, and moderately-differentiated type were considered differentiated adenocarcinoma, and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, signet-ring cell carcinoma, and mucinous adenocarcinoma were considered undifferentiated adenocarcinoma[9]. Gastric cancer in Mongolian patients included endoscopically operated patients (endoscopic submucosal dissection or endoscopic mucosal resection), surgically operated patients, patients not operated on, and inoperable patients. Biopsy specimens were used for the histologic diagnosis of gastric cancer. Cancers were diagnosed by a single Mongolian pathologist (T Baldandorj).

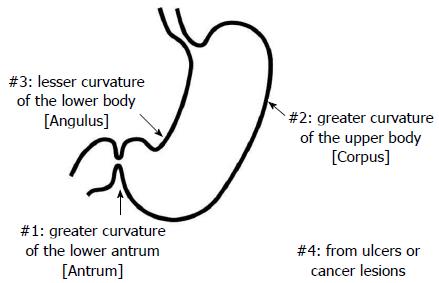

The triple-site biopsy method (Figure 1)[5,6,10,11] was used for the histologic diagnosis of gastritis and H. pylori infection in all Mongolian and Japanese cases. Chronic inflammation, neutrophil activity, glandular atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and H. pylori were scored using a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3 (0: none, 1: mild, 2: moderate, and 3: severe) based on the Updated Sydney system[12]. Specimen #1 was taken from the greater curvature of the lower antrum (antrum), specimen #2 was taken from the greater curvature of the upper corpus (corpus), and specimen #3 was taken from the lesser curvature of the lower corpus (angulus). Specimen #4 and others were taken from ulcers or cancer lesions.

In Mongolian endoscopy cases, all biopsy specimens were subjected to hematoxylin-eosin, Giemsa, and anti-East-Asian CagA-specific antibody (α-EAS Ab) staining in Japan[13]. α-EAS Ab is specifically immunoreactive with East-Asian CagA but not Western CagA. All Japanese cases were subjected to hematoxylin-eosin and Giemsa staining. One pathologist (N Yamada) diagnosed all sections to minimize any bias in the histologic diagnoses.

In total, 203 pairs from 208 Mongolian and 3205 Japanese patients matched by age (± 5 years), sex, and endoscopic diagnosis were used to compare the prevalence of H. pylori infection between the two countries.

From 158 H. pylori-positive Mongolian and 1736 H. pylori-positive Japanese patients matched by age (± 5 years), sex, and endoscopic diagnosis, 137 pairs of H. pylori-positive patients were used to compare the characteristics of gastric mucosa.

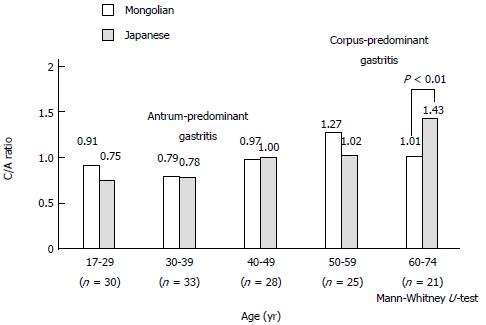

The C/A ratio was used to diagnose the type of gastritis in H. pylori-positive patients[10,11]. The C/A ratio in every age group was calculated using the mean score of C divided by the mean score of A. Patients with a C/A ratio < 1 were assessed as having antrum-predominant gastritis and those with a C/A ratio > 1 were assessed as having corpus-predominant gastritis.

McNemar’s test was used to compare the prevalence of H. pylori infection, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the gastric mucosa. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

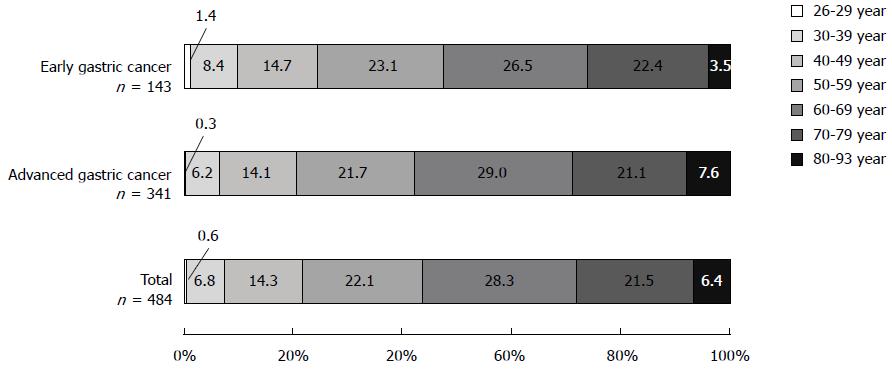

In 484 consecutive cases of gastric cancer in Mongolian patients, early gastric cancer accounted for 29.5% (143/484). When stratified by age group, total gastric cancer, early gastric cancer, and advanced gastric cancer were most frequent in patients in their 60s, followed by those in their 50s and then 70s, accounting for 71.9%, 72.0%, and 71.8% of these cancers, respectively (Figure 2). Moreover, 6.5%-9.8% of gastric cancer presented in young adults aged 39 years and younger. The male-to-female ratio was 1:0.51.

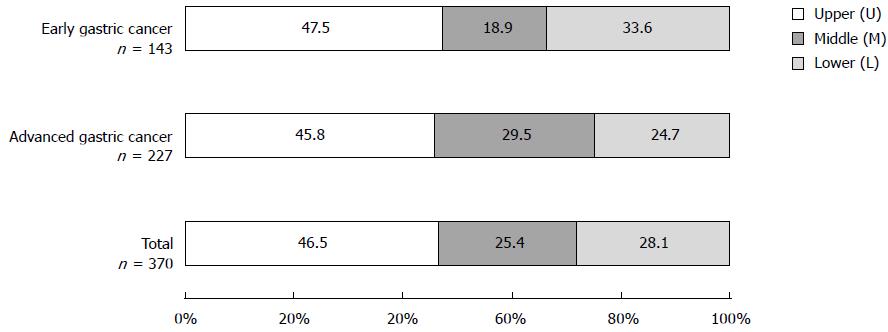

The percentages of the sites most affected by total gastric cancer were 46.5% in the U region, followed by 28.1% in the L region, and 25.4% in the M region (Figure 3). Lesions occurring in two or three regions (UM region: 91 cases, ML region: 16 cases, UML region: 7 cases; all were advanced gastric cancer) were excluded. The affected area of early gastric cancer and advanced gastric cancer was also largest in the U region (47.5% and 45.8%, respectively). Among gastric cancer in Mongolian patients, gastric cardia cancer accounted for 3.9% (19/484) of total gastric cancer.

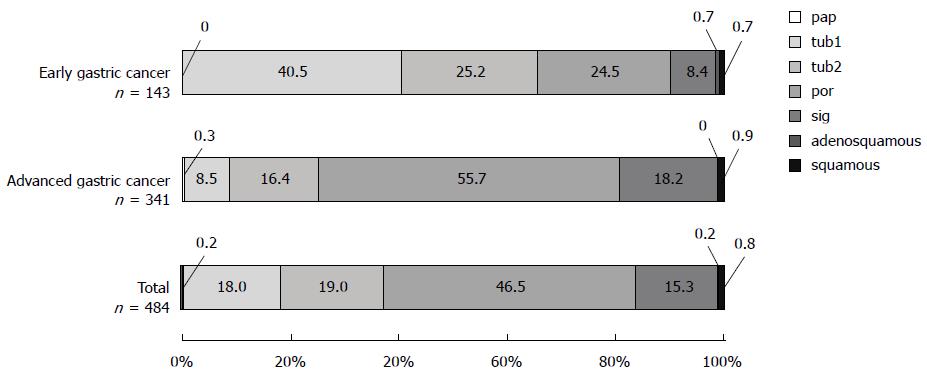

A greater percentage of total gastric cancer cases were undifferentiated adenocarcinoma (61.8%) than differentiated adenocarcinoma (37.2%). Similarly, in advanced gastric cancer, cases of undifferentiated adenocarcinoma (73.9%) were greater than those of differentiated adenocarcinoma (25.2%) (Figure 4). By contrast, in early gastric cancer, differentiated adenocarcinoma (65.7%) was more prevalent than undifferentiated adenocarcinoma (32.9%).

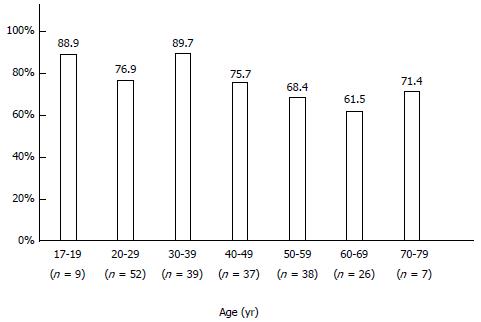

The infection rate of H. pylori was 76.0% (158/208 patients) in Mongolian patients. When stratified by age, H. pylori infection was highest among young people (< 19 years: 88.9%; 20-29 years: 76.9%; 30-39 years: 89.7%), and tended to decrease in people 50 years of age and older (50-59 years: 68.4%; 60-69 years: 61.5%; 70 years or older: 71.4%) (Figure 5).

The infection rate of H. pylori was higher in Mongolian than in Japanese patients (75.9% vs 48.3%, P < 0.0001).

α-EAS Ab was negative in 99.4% (157/158 patients) of H. pylori-positive Mongolian patients.

The mean scores for gastritis and H. pylori in the H. pylori-positive cases were all significantly lower in Mongolian patients than in Japanese patients (all P < 0.0001); the only exception was the intestinal metaplasia scores of specimen #2, which did not differ significantly between Mongolian and Japanese patients (Table 1).

| Nationality | Specimen | Chronic inflammation | Neutrophil activity | Glandular atrophy | Intestinal metaplasia | Helicobacter pylori | |||||

| Mongolian | #1 (antrum) | 1.32 ± 0.59 | P < 0.0001 | 0.38 ± 0.54 | P < 0.0001 | 0.15 ± 0.36 | P < 0.0001 | 0.07 ± 0.40 | P < 0.0001 | 0.93 ± 0.79 | P < 0.0001 |

| Japanese | 2.30 ± 0.72 | 2.05 ± 1.01 | 0.48 ± 1.72 | 0.34 ± 0.78 | 1.91 ± 1.01 | ||||||

| Mongolian | #2 (corpus) | 1.12 ± 0.50 | P < 0.0001 | 0.26 ± 0.47 | P < 0.0001 | 0.02 ± 0.19 | P < 0.0001 | 0.05 ± 0.35 | 1.08 ± 0.84 | P < 0.0001 | |

| Japanese | 2.03 ± 0.74 | 1.93 ± 0.96 | 0.28 ± 0.73 | 0.10 ± 0.44 | 2.20 ± 0.79 | ||||||

| Mongolian | #3 (angulus) | 1.50 ± 0.62 | P < 0.0001 | 0.55 ± 0.61 | P < 0.0001 | 0.16 ± 0.41 | P < 0.0001 | 0.17 ± 0.60 | P < 0.0001 | 1.15 ± 0.87 | P < 0.0001 |

| Japanese | 2.21 ± 0.80 | 1.93 ± 1.04 | 0.81 ± 1.02 | 0.59 ± 1.02 | 2.07 ± 0.95 | ||||||

The C/A ratio in 137 matched pairs of H. pylori-infected Mongolian and Japanese patients revealed antrum-predominant gastritis in < 49 years and 39 years, respectively, and corpus-predominant gastritis in patients > 50 years and 40 years, respectively (Figure 6). The mean C/A ratio of the Japanese patients > 60 years of age was higher than that of the Mongolian patients (1.43 vs 1.01; P < 0.01).

The incidence and mortality of gastric cancer are high in Eastern Asia and Central and Eastern Europe. According to the age-adjusted cancer incidence in Mongolian males, the liver is the most common cancer site (ASR: 97.8 cases per 100000 males), followed by the stomach (47.4 cases per 100000 males), lungs (27.7 cases per 100000 males), esophagus (21.2 cases per 100000 males), and colorectum (5.7 cases per 100000 males) (Globocan 2012)[3]. By contrast, in Japanese males, the stomach is the most common cancer site (45.8 cases per 100000 males), followed by the colorectum (42.1 cases per 100000 males), lungs (38.8 cases per 100000 males), prostate (30.4 cases per 100000 males) and liver (14.6 cases per 100000 males)[3]. In South Korean males, the stomach is also the most common cancer site (62.3 cases per 100000 males)[3]. South Korea, Mongolia, and Japan have the highest incidences of gastric cancer in the world. We previously examined gastric mucosa in relation to H. pylori infection in South Koreans[14], Chinese[6,11], Vietnamese[6,11], Thai[6,11], Burmese (Lecture, Nay Pyi Daw, Myanmar, 2008), Bangladeshi[4,5], and Nepalese[11] patients, and reported that atrophic and intestinal metaplasia scores were very high in Japanese and South Koreans. In this study, we investigated the characteristics of gastric cancer and the gastric mucosa in the context of H. pylori infection in Mongolian patients, who belong to the East Asian population, and compared them with those of Japanese patients.

Other than incidence and mortality, very few data relating to Mongolian patients with gastric cancer are available via PubMed. Therefore, we determined the ratio of early gastric cancer to total gastric cancer, age group frequency, region, and histologic type in Mongolian patients. Globally, gastric cancer is more common in men than women[3], and this is also true for Mongolian patients (male-to-female ratio 1:0.51). The percentage of early gastric cancer among total gastric cancer is 29.5% in Mongolian patients, which is lower than in Japanese cases (80%)[15]; the delayed spread of gastric examination screening, endoscopy devices, and early gastric cancer diagnostics in Mongolia may be determining factors. In addition, because H. pylori testing is not widespread in Mongolia, it is not clear if the cases included in this study were infected with H. pylori.

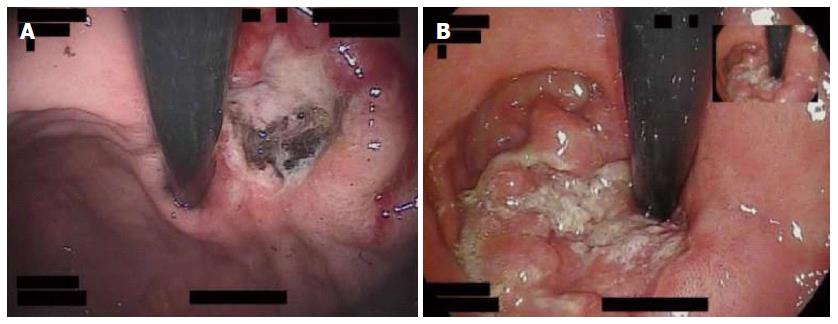

In countries and regions with a high incidence, gastric cancer occurs more frequently in the distal portion of the stomach; in countries and regions with a low incidence, gastric cancer occurs more frequently in the proximal portion[16]. Approximately half of the Japanese cases of gastric cancer occurred in the M region, (M > L > U)[15], while approximately half of the Mongolian gastric cancer cases occurred in the U region, indicating a considerable difference in the location frequency. Mongolians reportedly have high meat and salt intake (15 g/d). Other common practices include consuming large amounts of hot tea, regular alcohol intake, hurried eating, and low intake of fruit and vegetables[17,18]. Although H. pylori infection is not a risk factor for gastric cardia cancer[19], obesity is an onset risk factor of gastric cardia cancer[20,21]. Furthermore, obesity may influence the development of early gastric cancer and differentiated adenocarcinoma in males regardless of H. pylori infection[22]. No data regarding the degree of obesity in gastric cancer patients have been reported; however, the percentage of obese Mongolian adults (16.4%) is high compared with Japanese adults (4.5%) according to age-standardized data[23]. In this context, patients with a body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2 are defined as obese. Gastric cardia cancer accounted for 3.9% of total gastric cancer in Mongolian patients, and 3.2% of Japanese gastric cancer patients who underwent either endoscopic surgery or an open surgery in the previous decade[24]. Many cancers were located in the U region, including the cardia, in Mongolian patients (Figure 7), but the frequency of gastric cardia cancer does not differ compared to the Japanese patients. Because of the large number of advanced cancer cases among Mongolian patients, we must consider the possibility that gastric cardia cancers enlarged in size were classified as U region cancers. The factors (other than obesity) that contribute to the high incidence of gastric cancer in the U region remain to be determined. A detailed investigation of environmental factors and host factors is also necessary.

In Mongolian patients, the most prevalent histologic types of total, early, and advanced gastric cancers are undifferentiated adenocarcinoma, differentiated adenocarcinoma, and undifferentiated adenocarcinoma, respectively. In Japanese patients, undifferentiated adenocarcinoma was prevalent before the 1970s and differentiated adenocarcinoma has been dominant since the 1980s due to the aging of H. pylori-infected patients[15]. According to a report by Yamada et al[15], who examined 10132 patients who underwent surgical treatment in the 2000s, differentiated adenocarcinoma accounted for 68% and undifferentiated adenocarcinoma accounted for only 32% of cases. The trend of prevalent differentiated adenocarcinoma is weaker in advanced gastric cancer, but significantly stronger in early gastric cancer[16]. In Mongolian patients, differentiated adenocarcinoma is common in early gastric cancer, as in Japanese; however, a different trend was observed for advanced gastric cancer and total gastric cancer. The prevalence of undifferentiated adenocarcinoma in total gastric cancer in Mongolia may be due to differences in the criteria used by pathologist in Mongolia and the lower mean age of gastric cancer in Mongolian patients (60.5 years) compared to the Japanese patients (64 years)[15].

Based on the results of our field study in Asian countries, the gastric ulcer (GU)/duodenal ulcer (DU) ratiois different. There are big differences among Asian countries. Japanese[14] and South Korean[14] patients present as GU-predominant cases (1.69 and 1.75, respectively), whereas Bangladeshi[5] and Nepalese[11] present as DU-predominant cases (0.31 and 0.25, respectively). According to a personal communication with one Mongolian doctor who previously investigated this topic (O Khasag, Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences), Mongolia is a country of GU predominance (1.9 in 2003 based on unpublished data). Regarding the relationship between peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer, a higher GU/DU ratio in a country or region has been associated with a greater incidence of gastric cancer[25]. Furthermore, the development of gastric cancer is positively correlated with GU, but negatively correlated with DU[26]. Based on these reports, gastric cancer is likely to be common among Japanese, South Korean, and Mongolian patients.

Approximately half of the world’s population is infected with H. pylori, and the infection rate is higher in developing countries than in developed countries[27]. The infection rate of H. pylori is reported to be 5% or less in people younger than 20 years of age, and 40% in people in their 50s in developed countries[27]. In Japan, the infection rate is decreasing gradually, and the prevalence is 6.4% in children (0-12 years-old)[28] and 5.2% in high school students (16 or 17 years-old)[29]. In developing countries, the infection rate of H. pylori can be as high as 50% in teenagers and more than 90% in people in their 30s[30]. Our results indicate that H. pylori infection rates are high (76.0%) in Mongolian patient and very high in those 17-19 years of age (88.9%), revealing a developing country-type prevalence.

The Japanese are infected with East-Asian-type H. pylori, but the type of H. pylori that infects Mongolian patients has not been determined. Therefore, the Mongolian biopsies were stained with α-EAS Ab, which specifically reacts to East-Asian-type H. pylori. In H. pylori-positive Mongolian cases, the rate of α-EAS Ab positivity was 0.6% (1/158 H. pylori-positive cases), indicating that despite the location of Mongolia in East Asia, Mongolians are not infected with East-Asian-type H. pylori (i.e. Western-type CagA or CagA-negative strains). The H. pylori strains are currently being characterized by one of the authors (Y Yamaoka).

The scores for gastritis and H. pylori were significantly lower in H. pylori-infected Mongolian patients compared to Japanese patients at all gastric sites, with the exception of the intestinal metaplasia score in specimen #2. East-Asian-type H. pylori strains induce stronger chronic inflammation and neutrophil activity than Western-type H. pylori strains[31] and are involved in gastric mucosal atrophy and gastric cancer[32]. According to a report by Uemura et al[1], atrophic changes and intestinal metaplasia are strongly related to the risk of gastric cancer, and severe atrophic change, and intestinal metaplasia in particular, leads to a high risk of both intestinal-type and diffuse-type gastric cancer[9]. Because the South-Asian population is infected with Western-type H. pylori[33,34], glandular atrophy and intestinal metaplasia scores were significantly lower in Bangladeshi[5] and Nepalese[12] patients in our previously reported results. Therefore, the incidence of gastric cancer is very low in Bangladesh and Nepal (ASR: 7.2 cases per 100000 males and 7.4 cases per 100000 males, respectively)[3]. Although glandular atrophy and intestinal metaplasia scores are low in Mongolian patients, the incidence of gastric cancer is high; however, it is important to note that these scores were not obtained from patients with gastric cancer. To address this paradox, the gastric mucosa of Mongolian patients with gastric cancer should be examined. We are planning a gastric mucosal survey of patients with gastric cancer in Uvs, a western province with the highest prevalence of gastric cancer in Mongolia (ASR: 114.6 cases per 100000 males).

The prevalence of antrum-predominant gastritis tends to decrease with age in favor of corpus-predominant gastritis in Mongolian and Japanese patients. The C/A ratio in patients older than 60 years was higher in Japanese patients than in Mongolian patients. All age groups of Bangladeshi and Nepalese subjects had antrum-predominant gastritis[5,12]. The risk of gastric cancer is 23.3 times higher for corpus-predominant gastritis than for antrum-predominant gastritis[1]. This report is consistent with the low incidence of gastric cancer in South-Asian countries (Bangladesh and Nepal) and the high incidence in East-Asian countries (Japan, South Korea, and Mongolia). Therefore, a high C/A ratio, indicating corpus-predominant gastritis, is one of the causative factors of gastric cancer.

In conclusion, a comparative analysis of gastric mucosa in Mongolia and Japan, two countries with a high incidence of gastric cancer, was conducted. Gastric cancer occurred most frequently in the U region in Mongolian patients, and peaked among those in their 60s. The most prevalent histologic types of early and advanced gastric cancers are differentiated adenocarcinoma and undifferentiated adenocarcinoma, respectively. The infection rate of H. pylori was high in Mongolian patients, particularly those 1719 years-old. The scores for gastric mucosa may have been lower in the Mongolian patients compared to the Japanese patients because the majority were infected with non-East-Asian-type H. pylori strains. H. pylori-positive young Mongolian patients had antrum-predominant gastritis and developed more corpus-predominant gastritis with advanced age similar to the Japanese population. Further studies should clarify the reason for the high gastric cancer prevalence in Mongolian patients infected with non-East-Asian-type H. pylori.

We sincerely thank all medical staff at the Department of Gastroenterology, Health Sciences University of Mongolia, Department of Endoscopy, Ulaanbaatar Songdo Hospital, and Department of Gastroenterology, Third Central State Hospital, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, for all their work related to endoscopy. We also thank Hidenobu Watanabe, Emeritus Professor at the School of Medicine, Niigata University, Niigata, Japan for the histologic criterion of gastric cardia cancer, Nobutaka Yamada, former Assistant Professor in the Department of Pathology, Nippon Medical School, Tokyo, Japan, for the pathologic diagnoses of all Japanese biopsy specimens, and Nurse Yumi Sakamoto at Nippon Medical School Hospital, Nurse Kiyomi Suzuki at Daini Kokudou Hospital, and Nurse Sonomi Nawata at JR Kyusyu Hospital for their cooperation.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infections cause not only peptic ulcer disease, but also gastric cancer. Mongolia, South Korea, and Japan, which are located in Eastern Asia, have the highest incidence of gastric cancer in the world. Other than incidence and mortality, very few data relating to Mongolian patients with gastric cancer are available in PubMed. The characteristics of gastric cancer, H. pylori infection, and gastric mucosa were observed and compared between Mongolian and Japanese patients.

There are Western-type and East-Asian-type strains of H. pylori: the East-Asian-type strain influences the development of atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer greatly. There are no data regarding the type of H. pylori strain that tends to infect Mongolian patients or the gastric mucosa and type of gastritis in this population.

Gastric cancer occurred most frequently in the upper gastric region of Mongolian patients and peaked in those in their 60s. The most prevalent histologic types of early and advanced gastric cancers were differentiated adenocarcinoma and undifferentiated adenocarcinoma, respectively. The infection rate of H. pylori was high in Mongolian patients, particularly those 17-19 years-old. The majority of Mongolians were infected with non-East-Asian-type H. pylori strains (99.4%), which may explain the lower gastric mucosa scores when compared to Japanese patients. H. pylori-positive young Mongolian patient had antrum-predominant gastritis and developed more corpus-predominant gastritis with advanced age, similar to the Japanese patients.

There are many differences between Mongolian and Japanese patients in the location of gastric cancer, H. pylori strain type, and gastric mucosa. Future studies should clarify the reason for the high gastric cancer prevalence in Mongolian patients infected with non-East-Asian-type H. pylori.

The anti--Asian CagA-specific antibodies specifically immunoreactive with East-Asian CagA, but not Western CagA. Patients with a corpus/antrum activity ratio < 1 were assessed as having antrum-predominant gastritis, and those with a ratio > 1 were assessed as having corpus-predominant gastritis.

In this study, the authors investigated the characteristics of gastric cancer and gastric mucosa in Mongolian patients by comparing the gastric mucosa of Mongolian and Japanese patients. Approximately 70% of older Mongolians had gastric cancer, and approximately half of the Mongolian cancers were located in the upper part of the stomach. Three-fourths of advanced cancer displayed undifferentiated adenocarcinoma. Many differences in stomach characteristics were observed in Mongolian patients compared with Japanese patients. The prevalence of H. pylori infection was higher in Mongolian than in Japanese patients (75.9% vs 48.3%, P < 0.0001). The most surprising result was that 99.4% of H. pylori-positive cases were infected with non-East-Asian-type H. pylori. In general, this study is novel, interesting, and scientific, and, importantly, has clinical significance.

P- Reviewer: Shimada H, Zhang ZY S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: AmEditor E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3126] [Cited by in RCA: 3183] [Article Influence: 132.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fukase K, Kato M, Kikuchi S, Inoue K, Uemura N, Okamoto S, Terao S, Amagai K, Hayashi S, Asaka M. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:392-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 876] [Cited by in RCA: 935] [Article Influence: 55.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Default.aspx. |

| 4. | Matsuhisa T, Aftab H. Observation of upper gastrointestinal diseases and gastric mucosa in Bangladeshi population-comparison with Japanese. Bangladesh Med J. 2012;23:26-34. |

| 5. | Matsuhisa T, Aftab H. Observation of gastric mucosa in Bangladesh, the country with the lowest incidence of gastric cancer, and Japan, the country with the highest incidence. Helicobacter. 2012;17:396-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Matsuhisa TM, Yamada NY, Kato SK, Matsukura NM. Helicobacter pylori infection, mucosal atrophy and intestinal metaplasia in Asian populations: a comparative study in age-, gender- and endoscopic diagnosis-matched subjects. Helicobacter. 2003;8:29-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Miwa H, Go MF, Sato N. H. pylori and gastric cancer: the Asian enigma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1106-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Matsukura N, Yamada S, Kato S, Tomtitchong P, Tajiri T, Miki M, Matsuhisa T, Yamada N. Genetic differences in interleukin-1 betapolymorphisms among four Asian populations: an analysis of the Asian paradox between H. pylori infection and gastric cancer incidence. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2003;22:47-55. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2872] [Article Influence: 205.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Matsuhisa T, Matsukura N, Yamada N. Topography of chronic active gastritis in Helicobacter pylori-positive Asian populations: age-, gender-, and endoscopic diagnosis-matched study. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:324-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Matsuhisa T, Miki M, Yamada N, Sharma SK, Shrestha BM. Helicobacter pylori infection, glandular atrophy, intestinal metaplasia and topography of chronic active gastritis in the Nepalese and Japanese population: the age, gender and endoscopic diagnosis matched study. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2007;5:295-301. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3221] [Cited by in RCA: 3552] [Article Influence: 122.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 13. | Uchida T, Kanada R, Tsukamoto Y, Hijiya N, Matsuura K, Yano S, Yokoyama S, Kishida T, Kodama M, Murakami K. Immunohistochemical diagnosis of the cagA-gene genotype of Helicobacter pylori with anti-East Asian CagA-specific antibody. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:521-528. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Matsuhisa T. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastroduodenal diseases in East, Southeast, and South Asian countries. In: Kim BW, Lee JH, editors. Asian Perspective in Helicobacter Research. The 10th Japan-Korea Joint Symposium on Helicobacter pylori Infection 2013; 50-52. |

| 15. | Yamada M, Oda I, Taniguchi H, Kushima R. [Chronological trend in clinicopathological characteristics of gastric cancer]. Nihon Rinsho. 2012;70:1681-1685. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Sin HR, Curado MP, Ferlay J, Heanue M, Edwards B, Strom M. Processing of data. Cancer incidence in five continents, Vol. IX. Lyon: IARC Scientific Publications 2007; 67-94. |

| 17. | Moore MA, Aitmurzaeva G, Arsykulov ZA, Bozgunchiev M, Dikanbayeva SA, Igisinov G, Igisinov N, Igisinov S, Karzhaubayeva S, Oyunchimeg D. Chronic disease prevention research in Central Asia, the Urals, Siberia and Mongolia - past, present and future. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10:987-996. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Sandagdorj T, Sanjaajamts E, Tudev U, Oyunchimeg D, Ochir C, Roder D. Cancer incidence and mortality in Mongolia - National Registry Data. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:1509-1514. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Chen Y, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1169-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 625] [Cited by in RCA: 618] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kubo A, Corley DA. Body mass index and adenocarcinomas of the esophagus or gastric cardia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:872-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhang J, Su XQ, Wu XJ, Liu YH, Wang H, Zong XN, Wang Y, Ji JF. Effect of body mass index on adenocarcinoma of gastric cardia. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2658-2661. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Kim HJ, Kim N, Kim HY, Lee HS, Yoon H, Shin CM, Park YS, Park DJ, Kim HH, Lee KH. Relationship between body mass index and the risk of early gastric cancer and dysplasia regardless of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastric Cancer. 2014;Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.A904. |

| 24. | Yamada M, Kushima R, Oda I, Taniguchi H, Sekine S, Odagaki T, Abe S, Sou E, Yachida T, Sakamoto T. Yearly trends of adenocarcinoma of the esophago-gastric junction and Barrett’s adenocarcinoma, and association with Helicobacter pylori infection. Stomach and Intestine. 2011;46:1737-1749. |

| 25. | Chiba T. Helicobacter pylori infection in Asia. Helicobacter Res. 2000;4:11-15. |

| 26. | Van Zanten SJ, Dixon MF, Lee A. The gastric transitional zones: neglected links between gastroduodenal pathology and helicobacter ecology. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1217-1229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Megraud F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter pylori and gastroduodenal disease. London: Blackwell Scientific Publications 1993; 107-123. |

| 28. | Okuda M, Miyashiro E, Koike M, Okuda S, Minami K, Yoshikawa N. Breast-feeding prevents Helicobacter pylori infection in early childhood. Pediatr Int. 2001;43:714-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Akamatsu T, Ichikawa S, Okudaira S, Yokosawa S, Iwaya Y, Suga T, Ota H, Tanaka E. Introduction of an examination and treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection in high school health screening. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1353-1360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori: its epidemiology and its role in duodenal ulcer disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1991;6:105-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Azuma T. Helicobacter pylori CagA protein variation associated with gastric cancer in Asia. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:97-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Azuma T, Yamazaki S, Yamakawa A, Ohtani M, Muramatsu A, Suto H, Ito Y, Dojo M, Yamazaki Y, Kuriyama M. Association between diversity in the Src homology 2 domain--containing tyrosine phosphatase binding site of Helicobacter pylori CagA protein and gastric atrophy and cancer. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:820-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yamaoka Y, Orito E, Mizokami M, Gutierrez O, Saitou N, Kodama T, Osato MS, Kim JG, Ramirez FC, Mahachai V. Helicobacter pylori in North and South America before Columbus. FEBS Lett. 2002;517:180-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Yamaoka Y. Helicobacter pylori typing as a tool for tracking human migration. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:829-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |