Published online Jun 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i22.7008

Peer-review started: December 29, 2014

First decision: January 22, 2015

Revised: February 20, 2015

Accepted: April 9, 2015

Article in press: April 9, 2015

Published online: June 14, 2015

Processing time: 172 Days and 1.4 Hours

AIM: To examine whether poly-unsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) therapy is beneficial for improving nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

METHODS: In total, 78 patients pathologically diagnosed with NASH were enrolled and were randomly assigned into the control group and the PUFA therapy group (added 50 mL PUFA with 1:1 ratio of EHA and DHA into daily diet). At the initial analysis and after 6 mo of PUFA therapy, parameters of interest including liver enzymes, lipid profiles, markers of inflammation and oxidation, and histological changes were evaluated and compared between these two groups.

RESULTS: At the initial analysis, in patients with NASH, serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartase aminotransferase (AST) were slightly elevated. Triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, markers of systemic inflammation [C-reactive protein (CRP)] and oxidation [malondialdehyde (MDA)], as well as fibrosis parameters of type IV collagen and pro-collagen type III pro-peptide were also increased beyond the normal range. Six months later, ALT and AST levels were significantly reduced in the PUFA group compared with the control group. In addition, serum levels of TG and TC, CRP and MDA, and type IV collagen and pro-collagen type III pro-peptide were also simultaneously and significantly reduced. Of note, histological evaluation showed that steatosis grade, necro-inflammatory grade, fibrosis stage, and ballooning score were all profoundly improved in comparison to the control group, strongly suggesting that increased PUFA consumption was a potential way to offset NASH progression.

CONCLUSION: Increased PUFA consumption is a potential promising approach for NASH prevention and reversal.

Core tip: Epidemiologically, it has been reported that the prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is increasing significantly and its associated morbidities, including non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hepatic failure, also impose great health and economic burdens on individuals and the whole of society. Preliminary data from our study showed that 6 mo poly-unsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) therapy improved NASH, as reflected by laboratory examination and histological evaluation. Future study is warranted to investigate whether long-term consumption of PUFA could completely reverse NASH and reduce the incidence of hepatic failure.

- Citation: Li YH, Yang LH, Sha KH, Liu TG, Zhang LG, Liu XX. Efficacy of poly-unsaturated fatty acid therapy on patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(22): 7008-7013

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i22/7008.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i22.7008

Dyslipidemia, associated with increased plasma levels of triglyceride (TG) and total cholesterol (TC), is associated with a broad range of diseases such as atherosclerosis, metabolic syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases (NAFLD), etc[1-3]. Epidemiologically, it has been reported that the prevalence of NAFLD has increased in the past decades, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hepatic failure induced by NAFLD impose great burdens on the patients and the whole society[1,4,5]. Previously, some studies used lipid-modified medications to evaluate whether NAFLD or NASH could be ameliorated, and the outcomes were controversial[6,7]. For example, Laurin et al[6] showed that clofibrate treatment was not beneficial for the improvement of liver function and histological changes in patients with hypertriglycemia and NASH. Nevertheless, data from Basaranoglu et al[7] suggested that gemfibrozil therapy could profoundly ameliorate liver dysfunction in patients with NASH. Similarly, the outcomes with 3-hydroxy-3-metylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitor (statin) therapy in patients with NASH also produced conflicting results[8-10].

Poly-unsaturated fatty acid (PUFA), predominantly comprising eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexenoic acid (DHA), has been broadly used in daily life. Several sources of evidence indicate that PUFA is capable of improving lipid disorders as well as of ameliorating systemic inflammation and oxidation[11-13]. It is well known that the pathophysiological characteristics of NAFLD and NASH include lipid-overloaded and lobular inflammation within liver tissues[14,15]. Therefore, we hypothesized that PUFA therapy might be useful and beneficial for improving NASH. In order to investigate our hypothesis, we conducted a randomized, prospective, controlled but not blinded trial. We believed that data from our trial could shed promising light for future studies in investigating the optimal therapy for NAFLD and NASH.

All participants pathologically diagnosed with NASH according to the criteria were enrolled and written informed consents were obtained prior to randomization[16]. The current study was conducted in conformity to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics and research committees of our hospital. All participants were definitely ruled out of having secondary causes of NASH such as alcohol-induced (alcohol consumption ≥ 20 g/wk), medication-caused (such as tamoxifen and amiodarone), viral hepatitis and autoimmune diseases (primary biliary cirrhosis). In total, 78 participants were enrolled and randomly assigned into the control group (prescribed normal saline) and the PUFA therapy group (added 50 mL PUFA with 1:1 ratio of EHA and DHA into daily diet) for 6 mo. Additionally, both groups were advised to take modest physical exercise of 30 min at least 5 d/wk. Low-fat and low-cholesterol, and low carbohydrate diets were also recommended.

All working staff involved in evaluating parameters were blinded to the information about both groups. A fasting venous blood sample was drawn and parameters of interest, including lipid profiles [TG; TC; low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C); and high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C)], serum levels of liver enzymes [alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartase aminotransferase (AST)], total and direct bilirubin, fasting blood glucose (FBG) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were assessed by using the standard techniques of clinical chemistry laboratories. Serum levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), type IV collagen and pro-collagen type III pro-peptide (P-III-P) were detected in accordance to previous reports[17,18]. Body mass index (BMI), smoking status, family history of NASH and other demographic data were simultaneously collected by questionnaire. All the above parameters were evaluated at the initial visit and at 6 mo of PUFA therapy.

At the initial visit and at 6 mo of PUFA therapy, liver biopsy was performed to evaluate the changes of hepatic tissues. Notably, steatosis grade, necro-inflammatory grade, fibrosis stage and ballooning score of these two groups were evaluated by two experts in pathology.

Continuous variable was presented as mean ± SD and compared by the Student’s t-test when data was normally distributed, otherwise compared by Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical data was presented as percentage and compared by χ2 test. Statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS software version 18.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois). A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

As shown in Table 1, all parameters were comparable between the control and the PUFA therapy groups at the initial evaluation. Of note, more of the participants were male in this research, and most of the participants were overweight or obese. Serum levels of ALT and AST were slightly elevated in both groups. Lipid profiles revealed significantly increased serum levels of TG, TC and LDL-C. Markers of inflammation (CRP) and oxidation (MDA) were also elevated in patients with NASH. Fibrotic parameters such as type IV collagen and P-III=P were also higher than the normal range in patients with NASH.

| Variables | Total | Control | PUFA | P value |

| n | 78 | 39 | 39 | |

| Age (yr) | 51.9 ± 7.8 | 50.4 ± 7.2 | 52.6 ± 6.6 | 0.306 |

| Male, n (%) | 70 (89.7) | 36 (92.3) | 34 (87.2) | 0.178 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.9 ± 1.6 | 27.2 ± 1.3 | 28.0 ± 1.4 | 0.225 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 45 (57.7) | 22 (56.4) | 23 (59.0) | 0.154 |

| Family history, n (%) | 3 (3.8) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.1) | 0.237 |

| ALT (U/L) | 89.9 ± 10.4 | 91.3 ± 10.2 | 89.2 ± 12.4 | 0.313 |

| AST (U/L) | 82.4 ± 11.6 | 83.5 ± 8.9 | 82.0 ± 9.6 | 0.196 |

| Bilirubin, total (md/dL) | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.354 |

| Bilirubin, direct (md/dL) | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.366 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 6.1 ± 0.3 | 6.1 ± 0.2 | 6.1 ± 0.5 | 0.117 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 0.252 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.6 ± 0.7 | 5.5 ± 0.3 | 5.6 ± 0.4 | 0.408 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 0.387 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.163 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 10.4 ± 1.3 | 10.6 ± 1.1 | 10.0 ± 1.5 | 0.204 |

| MDA (nmol/mL) | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.339 |

| Type IV collagen (ng/mL) | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 0.286 |

| P-III-P (U/mL) | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.350 |

| Weekly exercise time (min) | 60.3 ± 7.3 | 61.2 ± 5.6 | 60.1 ± 4.6 | 0.313 |

As presented in Table 2, after 6 mo therapy, liver function was significantly improved in the PUFA group compared with the control group, as indicated by the significant reduction of ALT and AST levels. In addition, serum levels of TG and TC, CRP, MDA, type IV collagen and P-III-P were also significantly reduced in the PUFA group as compared to the control group. Of note, both the BMI and the percentage of smokers were reduced, while the exercise time per week was increased in both groups when compared to the initial assessment, and there was no significant difference in these improvements between the control and the PUFA therapy groups.

| Variables | Controlled | PUFA | P value |

| n | 39 | 39 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.4 ± 1.0 | 25.8 ± 1.2 | 0.065 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 15 (38.5) | 14 (35.9) | 0.278 |

| ALT (U/L) | 80.4 ± 7.6 | 67.8 ± 5.3 | < 0.01 |

| AST (U/L) | 75.6 ± 5.8 | 60.3 ± 6.8 | < 0.01 |

| Bilirubin, total (md/dL) | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.343 |

| Bilirubin, direct (md/dL) | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.338 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 5.9 ± 0.3 | 0.285 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 0.015 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 0.040 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 0.062 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.105 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 9.2 ± 0.8 | 7.6 ± 0.4 | 0.045 |

| MDA (nmol/mL) | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.048 |

| Type IV collagen (ng/mL) | 4.6 ± 0.7 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 0.023 |

| P-III-P (U/mL) | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.039 |

| Weekly exercise time (min) | 107.6 ± 12.3 | 109.5 ± 10.4 | 0.272 |

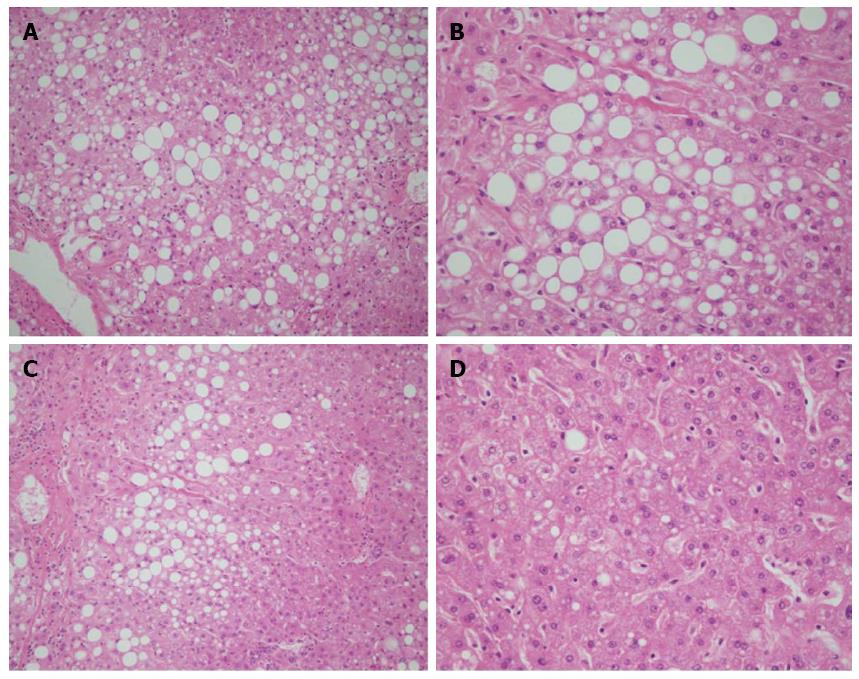

Briefly, as shown in Figure 1, at the initial evaluation the parameters indicating the histological characteristics of NASH were comparable between the control and the PUFA therapy groups (as also shown in Table 3). Nevertheless, with 6 mo PUFA therapy, all parameters demonstrating the severity of NASH were significantly improved when compared to the control group.

| Variables | Controlled | PUFA | P value |

| At the initial evaluation | |||

| Steatosis grade | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 0.355 |

| Necro-inflammatory grade | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 0.268 |

| Fibrosis stage | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 0.309 |

| Ballooning score | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.227 |

| Six months later | |||

| Steatosis grade | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 0.032 |

| Necro-inflammatory grade | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.017 |

| Fibrosis stage | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.020 |

| Ballooning score | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.015 |

The prevalence of NAFLD and NASH is gradually increasing and their associated morbidity and mortality impose a great burden on the whole of society[5,19]. Currently, there are no specific and highly-effective treatments for NAFLD and NASH. Previous epidemiological studies revealed the controversial outcomes with lipid-lowering therapy in patients with NASH[6-10]. Importantly, data from our current study shows that, as compared to the control group, 6 mo of PUFA therapy significantly decreases serum levels of liver enzymes. In addition, other crucial parameters including CRP, MDA, type IV collagen and P-III-P are also profoundly reduced. Histological assessment at 6 mo further corroborates the potential benefits of PUFA therapy on NASH.

In the past decades, many risk factors associated with NAFLD and NASH development have been identified[15,20,21]. Notably, dyslipidemia, resulting from over-consumption of cholesterol and triglycerides, is one the most critical elements for NASH development[20-22]. Knowingly[23,24], lipid accumulating in liver tissues is the first sign of NAFLD and HASH development. Subsequently, the second sign of hepatocyte injury, inflammation, oxidation and fibrosis ensues and accelerates NASH progression. Therefore, in light of the underlying mechanisms, many medications especially lipid-lowering agents have been used for the treatment of NAFLD and NASH. In addition, other medications such as insulin-sensitizing drugs (metformin and thiazolidinedione)[25,26] and antioxidants (Vitamin C and E) have also been tested in clinical studies[27], and disappointingly the outcomes were quite inconsistent.

Basically, PUFA is an essential nutrition for maintaining organ function properly, and previous studies also reveal that increased PUFA consumption is not only beneficial for lipid modification, but is also effective in glycemic control, hypertension management, endothelium protection and inflammation amelioration[28]. Taken together, we considered that it was reasonable to postulate that increased PUFA consumption might also be effective for NAFLD and NASH management. In our current research, we showed that with 6 mo of PUFA therapy, as compared to the control group, both the laboratory parameters of liver function and histological changes of hepatic tissues were profoundly improved, strongly suggesting that PUFA might be a potential promising candidate for NAFLD and NASH management. In light of previous reports regarding the underlying mechanisms associated with PUFA benefits, we speculated that the following mechanisms might be responsible for our favorable findings. Firstly, as mentioned before dyslipidemia plays a continuous role on NAFLD and NASH development. While PUFA is capable of ameliorating lipid disorders[28], and data from the present study also revealed that with 6 mo PUFA therapy serum levels of TG and TC were significantly reduced as compared to the control group. Importantly, after 6 mo of PUFA therapy, the steatosis grade was reduced, which also directly suggested that lipid accumulation in hepatic tissues could be improved with PUFA therapy. Secondly, the second sign in the process of NASH development is characterized by hepatic inflammation and oxidation. Therefore, amelioration of inflammation and oxidation might be a possible means to prevent or retard NASH progression. In our present study, we showed that after 6 mo PUFA therapy, serum levels of CRP and MDA were profoundly reduced as compared to the control group. Histological parameters, such as necro-inflammatory grade, were profoundly improved which also supported the notion that PUFA therapy was beneficial for ameliorating hepatic inflammation in patients with NASH[29]. Last but not the least, by inhibiting lipid accumulation and ameliorating inflammation, PUFA offset hepatic fibrosis as suggested by the decline of serum levels of type IV collagen and P-III-P. Histological evaluation further substantiated the fact that PUFA therapy was beneficial for improving hepatic fibrosis. Nevertheless, the mechanism associated with PUFA therapy for preventing and retarding hepatic fibrosis needs future investigation.

In conclusion, preliminary data from our study shows that 6 mo of PUFA therapy is beneficial for improving NASH, as reflected by the laboratory examination and histological evaluation. Further study is warranted to investigate whether long-term consumption of PUFA could completely reverse NASH and reduce the incidence of hepatic failure.

We appreciate very much the kindly help from Dr. Tian-You Yang.

Poly-unsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) has been used for the therapy of dyslipidemia, which is a key risk factor for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Whether PUFA is beneficial for improving NASH is unknown.

Increased PUFA consumption may be beneficial for NASH improvement.

Preliminary data from this study showed that 6 mo PUFA therapy improved NASH, as reflected by laboratory examination and histological evaluation. Further study is warranted to investigate whether long-term consumption of PUFA could completely reverse NASH and reduce the incidence of hepatic failure.

Current research may provide preliminary data for future studies investigating whether long-term PUFA therapy could further improve and reverse NASH.

Dyslipidemia, indicated by increased plasma levels of triglyceride and total cholesterol, is associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases (NAFLD) and NASH. Several sources of evidence have indicated that PUFA is capable of improving lipid disorders as well as ameliorating systemic inflammation and oxidation. It is well known that the pathophysiological characteristics of NAFLD and NASH are indicated by lipid-overloaded and lobular inflammation within liver tissues. Therefore, it is reasonable to postulate that PUFA therapy may be useful and beneficial to improve NASH.

The study objective is strongly justified as it is assumed that dyslipidemia resulting from over-consumption of cholesterol and triglycerides is a major risk factor for this pathology. In the future, this may have major clinical implications as potential validation of antifibrotic therapies in patients with this pathology.

P- Reviewer: Sarli B, Sobaniec-Lotowska ME S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: O’Neill M E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Masuoka HC, Chalasani N. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: an emerging threat to obese and diabetic individuals. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1281:106-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | DeFilippis AP, Blaha MJ, Martin SS, Reed RM, Jones SR, Nasir K, Blumenthal RS, Budoff MJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and serum lipoproteins: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2013;227:429-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Manickam P, Sudhakar R. Dyslipidemia and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ballestri S, Lonardo A, Bonapace S, Byrne CD, Loria P, Targher G. Risk of cardiovascular, cardiac and arrhythmic complications in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1724-1745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Lazo M, Hernaez R, Eberhardt MS, Bonekamp S, Kamel I, Guallar E, Koteish A, Brancati FL, Clark JM. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:38-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 633] [Cited by in RCA: 625] [Article Influence: 52.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Laurin J, Lindor KD, Crippin JS, Gossard A, Gores GJ, Ludwig J, Rakela J, McGill DB. Ursodeoxycholic acid or clofibrate in the treatment of non-alcohol-induced steatohepatitis: a pilot study. Hepatology. 1996;23:1464-1467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Basaranoglu M, Acbay O, Sonsuz A. A controlled trial of gemfibrozil in the treatment of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kiyici M, Gulten M, Gurel S, Nak SG, Dolar E, Savci G, Adim SB, Yerci O, Memik F. Ursodeoxycholic acid and atorvastatin in the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17:713-718. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Gómez-Domínguez E, Gisbert JP, Moreno-Monteagudo JA, García-Buey L, Moreno-Otero R. A pilot study of atorvastatin treatment in dyslipemid, non-alcoholic fatty liver patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1643-1647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rallidis LS, Drakoulis CK, Parasi AS. Pravastatin in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: results of a pilot study. Atherosclerosis. 2004;174:193-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kazemian P, Kazemi-Bajestani SM, Alherbish A, Steed J, Oudit GY. The use of ω-3 poly-unsaturated fatty acids in heart failure: a preferential role in patients with diabetes. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2012;26:311-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lluís L, Taltavull N, Muñoz-Cortés M, Sánchez-Martos V, Romeu M, Giralt M, Molinar-Toribio E, Torres JL, Pérez-Jiménez J, Pazos M. Protective effect of the omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: Eicosapentaenoic acid/Docosahexaenoic acid 1: 1 ratio on cardiovascular disease risk markers in rats. Lipids Health Dis. 2013;12:140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Calzolari I, Fumagalli S, Marchionni N, Di Bari M. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and cardiovascular disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:4094-4102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Castaño D, Larequi E, Belza I, Astudillo AM, Martínez-Ansó E, Balsinde J, Argemi J, Aragon T, Moreno-Aliaga MJ, Muntane J. Cardiotrophin-1 eliminates hepatic steatosis in obese mice by mechanisms involving AMPK activation. J Hepatol. 2014;60:1017-1025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dyson JK, Anstee QM, McPherson S. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a practical approach to diagnosis and staging. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2014;5:211-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tripodi A, Fracanzani AL, Primignani M, Chantarangkul V, Clerici M, Mannucci PM, Peyvandi F, Bertelli C, Valenti L, Fargion S. Procoagulant imbalance in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2014;61:148-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cai F, Dupertuis YM, Pichard C. Role of polyunsaturated fatty acids and lipid peroxidation on colorectal cancer risk and treatments. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2012;15:99-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Karttunen T, Sormunen R, Risteli L, Risteli J, Autio-Harmainen H. Immunoelectron microscopic localization of laminin, type IV collagen, and type III pN-collagen in reticular fibers of human lymph nodes. J Histochem Cytochem. 1989;37:279-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Perseghin G. The role of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in cardiovascular disease. Dig Dis. 2010;28:210-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ogawa Y, Imajo K, Yoneda M, Nakajima A. [Pathophysiology of NAsh/NAFLD associated with high levels of serum triglycerides]. Nihon Rinsho. 2013;71:1623-1629. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Feijó SG, Lima JM, Oliveira MA, Patrocínio RM, Moura-Junior LG, Campos AB, Lima JW, Braga LL. The spectrum of non alcoholic fatty liver disease in morbidly obese patients: prevalence and associate risk factors. Acta Cir Bras. 2013;28:788-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ioannou GN. The natural history of NAFLD: impressively unimpressive. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Duvnjak M, Lerotić I, Barsić N, Tomasić V, Virović Jukić L, Velagić V. Pathogenesis and management issues for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4539-4550. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Day CP, James OF. Steatohepatitis: a tale of two “hits”? Gastroenterology. 1998;114:842-845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2953] [Cited by in RCA: 3129] [Article Influence: 115.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 25. | Marchesini G, Brizi M, Bianchi G, Tomassetti S, Zoli M, Melchionda N. Metformin in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Lancet. 2001;358:893-894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 502] [Cited by in RCA: 479] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Buckingham RE. Thiazolidinediones: Pleiotropic drugs with potent anti-inflammatory properties for tissue protection. Hepatol Res. 2005;33:167-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Harrison SA, Torgerson S, Hayashi P, Ward J, Schenker S. Vitamin E and vitamin C treatment improves fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2485-2490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 505] [Cited by in RCA: 484] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mäntyselkä P, Niskanen L, Kautiainen H, Saltevo J, Würtz P, Soininen P, Kangas AJ, Ala-Korpela M, Vanhala M. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations of circulating omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids with lipoprotein particle concentrations and sizes: population-based cohort study with 6-year follow-up. Lipids Health Dis. 2014;13:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Roncaglioni MC, Tombesi M, Avanzini F, Barlera S, Caimi V, Longoni P, Marzona I, Milani V, Silletta MG, Tognoni G. n-3 fatty acids in patients with multiple cardiovascular risk factors. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1800-1808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 434] [Cited by in RCA: 389] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |