Published online May 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.6072

Peer-review started: September 21, 2014

First decision: November 14, 2014

Revised: December 11, 2014

Accepted: January 8, 2015

Article in press: January 8, 2015

Published online: May 21, 2015

Processing time: 243 Days and 7 Hours

Epstein Barr virus (EBV) positive mucocutaneous ulcers (EBVMCU) form part of a spectrum of EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disease. They have been reported in the setting of immunosenescence and iatrogenic immunosuppression, affecting the oropharyngeal mucosa, skin and gastrointestinal tract (GIT). Case reports and series to date suggest a benign natural history responding to conservative management, particularly in the GIT. We report an unusual case of EBVMCU in the colon, arising in the setting of immunosuppression in the treatment of Crohn’s disease, with progression to Hodgkin lymphoma 18 mo after cessation of infliximab. The patient presented with multiple areas of segmental colonic ulceration, histologically showing a polymorphous infiltrate with EBV positive Reed-Sternberg-like cells. A diagnosis of EBVMCU was made. The ulcers failed to regress upon cessation of infliximab and methotrexate for 18 mo. Following commencement of prednisolone for her Crohn’s disease, the patient developed widespread Hodgkin lymphoma which ultimately presented as a life-threatening lower GIT bleed requiring emergency colectomy. This is the first report of progression of EBVMCU to Hodgkin lymphoma, in the setting of ongoing iatrogenic immunosuppression and inflammatory bowel disease.

Core tip: This is the first reported case of Epstein Bar virus mucocutaneous ulcer (EBVMCU) affecting the gastrointestinal tract progressing to widespread Hodgkin lymphoma in the context of iatrogenic immunosuppression in the treatment of Crohns disease. EBVMCU is a newly recognised clinico-pathological condition that was previously thought to have a benign natural history. This case highlights the malignant potential of this disease entity even after withdrawal of immunosuppression.

- Citation: Moran NR, Webster B, Lee KM, Trotman J, Kwan YL, Napoli J, Leong RW. Epstein Barr virus-positive mucocutaneous ulcer of the colon associated Hodgkin lymphoma in Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(19): 6072-6076

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i19/6072.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.6072

Epstein Barr virus (EBV) infection is a ubiquitous herpes virus. After primary infection at an early age, EBV establishes latent infection in B-cells. A higher EBV prevalence rate is found in immunosuppressed compared to healthy individuals[1]. EBV is able to elicit B-cell transformation and proliferation which is kept in check by T-cell immune surveillance[2,3]. Iatrogenic immunosuppression for autoimmune disorders and in the post-transplant setting as well as age-related immunosenescence can lead to the emergence of EBV-positive B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs). In the setting of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the gastrointestinal mucosa has been identified as a site of EBV replication[2] and reactivation of EBV is more frequent among patients with IBD[4]. EBV has been linked with the development of lymphoma in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT)[5].

EBV positive mucocutaneous ulcers (EBVMCU) were first identified as a distinct clinico-pathological entity in 2010. Dojcinov et al[6] reported a study of 26 cases of ulcerative lesions arising in the skin, oropharynx and GIT in the context of immunosuppression, including age-related immunosenescence and iatrogenic immunosuppression for autoimmune diseases. These lesions displayed an indolent self-limited course, often regressing spontaneously or with reduction of immunosuppression, and with no reports of progression to disseminated disease. The entity shows an infiltrate of EBV+ atypical large Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg (HRS)-like cells with a polymorphous inflammatory background, mimicking classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL). Hence, a diagnosis of EBVMCU requires a combination of clinical, morphologic and immunophenotypic parameters. Since that classification, EBVMCU have been increasingly reported in the literature particularly relating to iatrogenic immunosuppression, with methotrexate[7,8] azathioprine[6,9,10] and ciclosporin[6] therapy.

Reports of EBVMCU affecting the GIT have been limited. Case reports to date suggest an indolent course with regression following withdrawal of immunosuppression[7,9]. Dojcinov et al[6] described four cases involving the gastrointestinal tract, all of which achieved complete remission with either no intervention, or with reduction of immunosuppression. In one case no intervention was required, whereas in the other cases a reduction of immunosuppression induced regression of the EBVMCU. There was no malignant progression and no need for treatment cessation or further intervention. This is the first case report of an IBD-associated EBVMCU with progression to cHL.

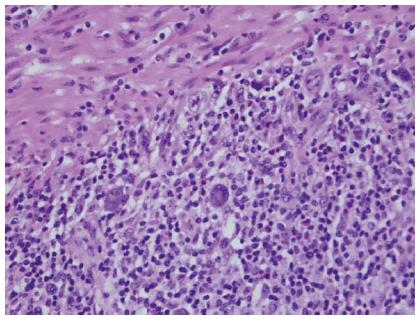

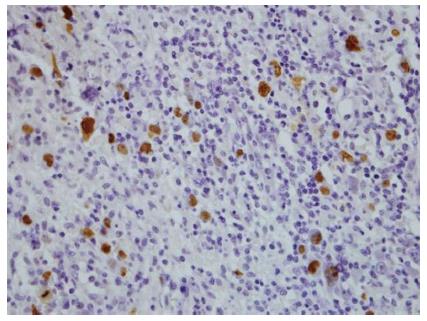

We present an unusual case of primary colorectal Hodgkin Lymphoma in a 53-year-old woman with a six year history of histologically confirmed Crohn’s disease (CD). She had glandular fever in her teenage years and no other significant past medical history. There was no personal or family history of primary immunodeficiency. Initial CD treatment was with aminosalicylates and corticosteroids but escalated to immunomodulators for recurrent need for steroids. Due to azathioprine intolerance, methotrexate was substituted. She had primary non-response to induction and six months maintenance of adalimumab, and induction and maintenance infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 wk was commenced together with methotrexate. One year later surveillance colonoscopy revealed ulceration at the splenic flexure, sigmoid colon and rectum. Colonoscopic biopsies showed a polymorphous infiltrate in the lamina propria containing large atypical HRS-like cells in a background of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils and eosinophils (Figure 1). The polyclonal atypical cells showed a classic Hodgkin lymphoma like immunophenotype with positivity for CD30, weak positivity for PAX5, strong positivity for MUM-1 and variable positivity for CD20, CD15, and OCT2. The atypical cells were positive for EBV-encoded small RNAs (EBER) by in situ hybridisation (ISH) (Figure 2). The morphological appearance, immunohistochemical profile and clinical context were consistent with EBVMCU without clonal proliferation. Methotrexate and infliximab were discontinued and repeat colonoscopy at 2, 6, 12 and 18 mo after cessation showed persistence of the colorectal ulcers (Figure 3). Subsequent colonoscopic biopsies with reduced immunosuppression still showed persistence of the ulcers with similar histological findings. Surgical resection was strongly considered if it were not for the benign course of the condition in small case series, the patient’s refusal for ileostomy and the distal location of one EBVMCU which was unable to be easily resectable with primary intestinal anastomosis.

The patient was completely off immunosuppression for 18 mo and was only taking 5-aminosalicylates. CD control was sub-optimal requiring recommencement of prednisolone. The ulcers showed some improvement following treatment with prednisolone 40 mg daily. Extensive multi-disciplinary discussion reaffirmed the diagnosis of an EBVMCU given the superficial localised nature of the ulceration and the presence of atypical EBV-positive lymphoid infiltrate and absence of clonal expansion. Within two months of commencing prednisolone, the patient had presented with fever and nausea. A computed tomography scan revealed multiple circumscribed liver lesions. Biopsies of the splenic flexure and sigmoid colon ulceration remained consistent with EBVMCU. Ultrasound-guided cores biopsies of the liver lesions showed a polymorphous inflammatory infiltrate with HRS cells which were CD30, CD15, MUM1 and weakly PAX5 positive; negative for CD45, OCT2 and BOB1; and EBER ISH positive; an immunophenotype indistinguishable from cHL.

Soon after, the patient presented with life-threatening rectal haemorrhage requiring an emergency colectomy with end ileostomy. Macroscopically, multiple large transmural colonic ulcers were present in the colon, measuring up to 15 cm in size and extending through the muscularis propria. Mesenteric lymphadenopathy was present. Microscopically, there was a transmural involvement of the bowel wall and local lymph nodes by an identical process to that in the liver, features consistent with a diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), mixed cellularity. Urgent chemotherapy with adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine was commenced. PET negative status was achieved after two months of chemotherapy and the patient remained in complete remission after six cycles.

EBVMCU has been described as indolent in its clinical behaviour, in most cases responding to withdrawal of immunosuppression. This is the first reported case of gastrointestinal tract EBVMCU progressing to classical Hodgkin Lymphoma despite cessation of infliximab and methotrexate some 18 mo previously.

The GIT is a common extranodal primary site of lymphoma especially B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Primary GIT cHL is rare, representing only a minority of primary GIT lymphomas and < 0.5% of all cHL[11,12]. There are few reports of EBVMCU involving the GIT and specifically the colon. However, due to the need for clinicopathological correlation to diagnose EBVMCU, there is the possibility that cases in the literature diagnosed as cHL or other LPDs represent genuine cases of EBVMCU. In this case report, the finding of EBVMCU which failed to progress with cessation of immunosuppression and subsequent development of cHL when prednisolone was reinstated is suggestive of EBVMCU as a precursor of cHL. Although the histomorphologic and immunophenotypic characteristics of the HRS-like cells from the colonic ulcers were indistinguishable from cHL, EBVMCU were initially diagnosed instead of cHL because she remained haematologically well throughout the persistence of the ulcers. It was only upon reinstatement of the immunosuppression and evidence of progression in the form of liver, transmural colonic and nodal involvement by the HRS-like cells that cHL was diagnosed. In our opinion, this highlights the point that EBVMCU should be a clinico-pathological diagnosis. It is known that molecular studies for immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) gene rearrangement on microdissected HRS cells were performed on a case consistent with EBVMCU and a case of systemic disease[13]. Monoclonal IgH rearrangement was found in the case of systemic disease whilst the localised disease was polyclonal. This is suggestive that EBVMCU represents an early polyclonal EBV-driven LPD which may show molecular progression to cHL, analogous to post-transplant LPDs, in which polymorphic B-cell proliferations may regress upon removal of immunosuppression, or progress to lymphoma[14].

There is significant concern regarding the risk of developing lymphoma associated with immunosuppressive therapy in IBD. Population based studies have demonstrated an increased risk of lymphoma in patients treated with thiopurines[15], and more recently a meta-analysis confirmed a higher lymphoma risk in patients treated with thiopurines which reduces with discontinuation of therapy[16]. The refurbish study demonstrated an increased incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma with combination tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and thiopurine use but not in TNF-α monotherapy[17]. Cases of EBV-associated colonic B-cell lymphoma following treatment with infliximab for IBD have however been reported[5], as well as regression of colonic lymphoma following infliximab and thiopurine withdrawal[18].

Our patient only had azathioprine temporarily and infliximab for 12 mo prior to its cessation. Failure of the EBV MCU to regress despite cessation of immunosuppression may also be secondary to the inherent immunodysregulation present in some patients with IBD[19,20]. This constitutional failure of immune-surveillance may predispose patients with IBD to the emergence of EBV driven LPDs.

The natural history of EBVMCU in the setting of immunosuppression in IBD is poorly understood. What is apparent, however, is that EBVMCU can fail to regress despite cessation of immunosuppressive therapy and in fact progress towards cHL. Failure of EBVMCU to regress after cessation of immunosuppression for over 12 mo may an indication for localised intestinal resection, if amenable.

Colonoscopy revealed ulceration at the splenic flexure, sigmoid colon and rectum which histological analysis of biopsies confirmed as Epstein Barr virus positive mucocutaneous ulcers (EBVMCU).

EBVMCU developed in the context of immunosuppression for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. These were initially considered benign given the available evidence in the literature. The patient main remained asymptomatic.

Clinico-pathological diagnosis.

Abdomen computed tomography revealed multiple circumscribed liver lesions suspicious for metastasis 18 mo following withdrawal of immunosuppression.

Histological analysis revealed atypical cells showing a classic Hodgkin lymphoma like immunophenotype with positivity for CD30, weak positivity for PAX5, strong positivity for MUM-1 and variable positivity for CD20, CD15, and OCT2 - consistent with a diagnosis of EBVMCU.

Previous reports suggested resolution of EBVMCU on withdrawal of immunosuppressive therapy - however in this case the EBVMCU progressed to Hodgkin Lymphoma despite treatment cessation 18 mo previously.

There are limited reports of EBVMCU in the gastrointestinal tract. Previously reported cases have demonstrated a benign natural history, with regression following cessation of immunosuppressive therapy.

This case reports the important finding of potential malignant progression in Epstein Barr virus mucocutaneous ulcers in the setting of iatrogenic immunosuppression.

The rectal circumferential ulcer was too distal to allow sufficient margin for an end-to-end anastomosis of low anterior resection. It was visualised by the author and on further discussion with the patient she was not prepared for the quality-of-life consequence of an AP resection. The authors had considered surgery and even tattooed the lesions with India Ink endoscopically in preparation for guiding surgical resection. However, the patient did not provide consent in light of cases of EBVMCU demonstrating a benign outcome.

P- Reviewer: Actis GC, Zezos P S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Ling PD, Lednicky JA, Keitel WA, Poston DG, White ZS, Peng R, Liu Z, Mehta SK, Pierson DL, Rooney CM. The dynamics of herpesvirus and polyomavirus reactivation and shedding in healthy adults: a 14-month longitudinal study. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1571-1580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Thorley-Lawson DA, Gross A. Persistence of the Epstein-Barr virus and the origins of associated lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1328-1337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 735] [Cited by in RCA: 738] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ng SB, Khoury JD. Epstein-Barr virus in lymphoproliferative processes: an update for the diagnostic pathologist. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:40-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Magro F, Santos-Antunes J, Albuquerque A, Vilas-Boas F, Macedo GN, Nazareth N, Lopes S, Sobrinho-Simões J, Teixeira S, Dias CC. Epstein-Barr virus in inflammatory bowel disease-correlation with different therapeutic regimens. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1710-1716. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Allen PB, Laing G, Connolly A, O’Neill C. EBV-associated colonic B-cell lymphoma following treatment with infliximab for IBD: a new problem? BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013200423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dojcinov SD, Venkataraman G, Raffeld M, Pittaluga S, Jaffe ES. EBV positive mucocutaneous ulcer--a study of 26 cases associated with various sources of immunosuppression. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:405-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sadasivam N, Johnson RJ, Owen RG. Resolution of methotrexate-induced Epstein-Barr virus-associated mucocutaneous ulcer. Br J Haematol. 2014;165:584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hashizume H, Uchiyama I, Kawamura T, Suda T, Takigawa M, Tokura Y. Epstein-Barr virus-positive mucocutaneous ulcers as a manifestation of methotrexate-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:276-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | McGinness JL, Spicknall KE, Mutasim DF. Azathioprine-induced EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:377-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Subramaniam K, Cherian M, Jain S, Latimer M, Corbett M, D’Rozario J, Pavli P. Two rare cases of Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disorders in inflammatory bowel disease patients on thiopurines and other immunosuppressive medications. Intern Med J. 2013;43:1339-1342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lewin KJ, Ranchod M, Dorfman RF. Lymphomas of the gastrointestinal tract: a study of 117 cases presenting with gastrointestinal disease. Cancer. 1978;42:693-707. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Thomas DB, Huston BM, Lamm KR, Maia DM. Primary Hodgkin‘s disease of the sigmoid colon: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121:528-532. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kumar S, Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kingma DW, Sorbara L, Raffeld M, Banks PM, Jaffe ES. Epstein-Barr virus-positive primary gastrointestinal Hodgkin’s disease: association with inflammatory bowel disease and immunosuppression. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:66-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Knowles DM, Cesarman E, Chadburn A, Frizzera G, Chen J, Rose EA, Michler RE. Correlative morphologic and molecular genetic analysis demonstrates three distinct categories of posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 1995;85:552-565. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sokol H, Beaugerie L, Maynadié M, Laharie D, Dupas JL, Flourié B, Lerebours E, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Allez M, Simon T. Excess primary intestinal lymphoproliferative disorders in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2063-2071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kotlyar DS, Lewis JD, Beaugerie L, Tierney A, Brensinger CM, Gisbert JP, Loftus EV, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Blonski WC, Van Domselaar M. Risk of Lymphoma in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treated With Azathioprine and 6-Mercaptopurine: A Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:847-858.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Deepak P, Sifuentes H, Sherid M, Stobaugh D, Sadozai Y, Ehrenpreis ED. T-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas reported to the FDA AERS with tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors: results of the REFURBISH study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:99-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Flynn AD, Azar JM, Chiorean MV. Spontaneous regression of colonic lymphoma following infliximab and azathioprine withdrawal in patients with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:E69-E70. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Glocker E, Grimbacher B. Inflammatory bowel disease: is it a primary immunodeficiency? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:41-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Xu XR, Liu CQ, Feng BS, Liu ZJ. Dysregulation of mucosal immune response in pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3255-3264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |