Published online May 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.6026

Peer-review started: October 26, 2014

First decision: November 14, 2014

Revised: November 26, 2014

Accepted: December 16, 2014

Article in press: December 16, 2014

Published online: May 21, 2015

Processing time: 208 Days and 19.3 Hours

AIM: To provide a quantitative assessment of the association between type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC).

METHODS: Systematic review was conducted thorough MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and ISI Web of knowledge databases till 31st January 2014. This meta-analysis included the cohort studies that illustrated relative risk (RR) or odds ratio estimates with 95%CI for the predictive risk of CRC by T2DM. Summary relative risks with 95%CI were analyzed by using an effects summary ratio model. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed by the Cochran’s Q and I2 statistics.

RESULTS: The meta analysis of 8 finally selected studies showed a positive correlation of T2DM with the risk of CRC as depicted by effects summary RR of 1.21 (95%CI: 1.02-1.42). Diabetic women showed greater risk of developing CRC as their effect summary RR of 1.22 (95%CI: 1.01-49) with significant overall Z test at 5% level of significance was higher than the effect summary RR of 1.17 (95%CI: 1.00-1.37) of men showing insignificant Z test. The effect summary RR of 1.19 with 95%CI of 1.07-1.33 indicate a positive relationship between DM and increased risk of CRC with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 92% and P-value < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Results from this systematic review and meta-analysis report that diabetic people have an increased risk of CRC as compared to non-diabetics.

Core tip: The prevalence of diabetes for all age groups worldwide is estimated to be 2.8% in 2000 and 4.4% in 2030. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is associated with increased insulin resistance and insulin has been reported to exhibit procarcinogenic effects in a number of human systems including colon and rectum. This meta-analysis of 8 relevant cohort studies showed an increased risk for colorectal carcinoma by T2DM, and this association was more evident in diabetic women than men.

- Citation: Guraya SY. Association of type 2 diabetes mellitus and the risk of colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis and systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(19): 6026-6031

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i19/6026.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.6026

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has been reported to increase the risks of a wide spectrum of cancers including kidney[1], non-small-cell lung[2], pancreas[3], early gastric[4], ovarian[5], prostate[6], and colorectal cancer (CRC)[7]. The hallmark of T2DM is its associated insulin resistance, and in the majority, with compensatory hyperinsulinemia. As of 2010, more than 250 million people are suffering from T2DM worldwide; and this number is expected to reach 380 million in 20 years[8] (Chowdhury, 2010 #887). CRC is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths world-wide[9] and is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States for both men and women[10]. Because of the magnitude of the prevalence of T2DM and CRC and reports of published data suggesting a causal role of T2DM in the development of CRC[11,12], the frequency of relationship of these two illnesses needs to be investigated. Thus, exploring the association between T2DM and the risk of CRC is of clear significance.

Published data has shown inconsistent findings about the association of T2DM with the risk of CRC. There are also inconclusive results about the gender predominance and subsite in the colorectum harboring cancerous growths. This meta-analysis quantitatively assesses the results from published cohort studies to provide a more precise estimate of the association between T2DM as a possible predictor of the risk of CRC.

Systematic review was conducted to explore the association of T2DM with the risk of CRC thorough MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and ISI Web of knowledge databases till 31st January 2014. Only English language original studies conducted on human subjects were considered with the following eligibility criteria: (1) Cohort studies which explored the risk of CRC by DM; and (2) Empirical studies with appropriate data for investigating RR with relation to CRC and DM.

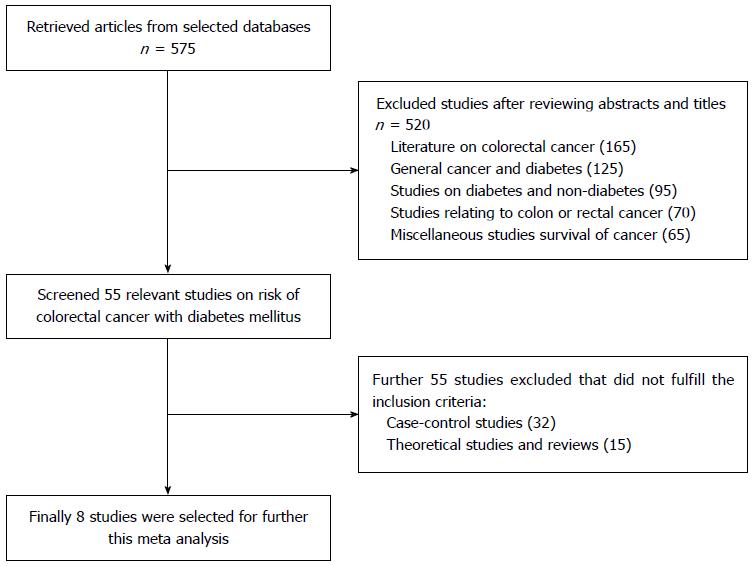

Data was retrieved by connecting MeSH terms (“colorectal cancer” and “diabetes” and “risk” or “colon cancer” or “rectal cancer”) in Endnote X5 which retrieved 575 citations as shown in Figure 1. After analysis of abstracts and titles 520 studies were excluded as irrelevant because these studies did not meet the inclusion criteria. During full text analysis of the remaining 55 relevant studies, 32 case-control and 15 theoretical and review articles were furtherer excluded. Only 8 relevant cohort studies were selected for further analysis. In this study, meta-analysis was done by using Forest plot which graphically presents the consistency and reliability of the results of selected studies. Forest plot was developed through Review Manager 5.3 software by Cochrane Library[13]. In this plot, effect size of each study is computed as an outcome and pooled effect size is also calculated to observe the heterogeneity among studies. Q test was used as a tool for verifying the heterogeneity in selected studies and its null hypothesis was that “all studies are identical”. The I2 statistic is an excellent method to ensure the quantity of heterogeneity in percentage terms and consistency of results of the selected studies[14]. After carefully analyzing the heterogeneity, next step is to apply appropriate effect summary model fixed effects or random effects model. If heterogeneity is low then it’s better to apply fixed effects model while random effects is most commonly used model when heterogeneity is higher. The level of significance in this study is 5% (P < 0.05).

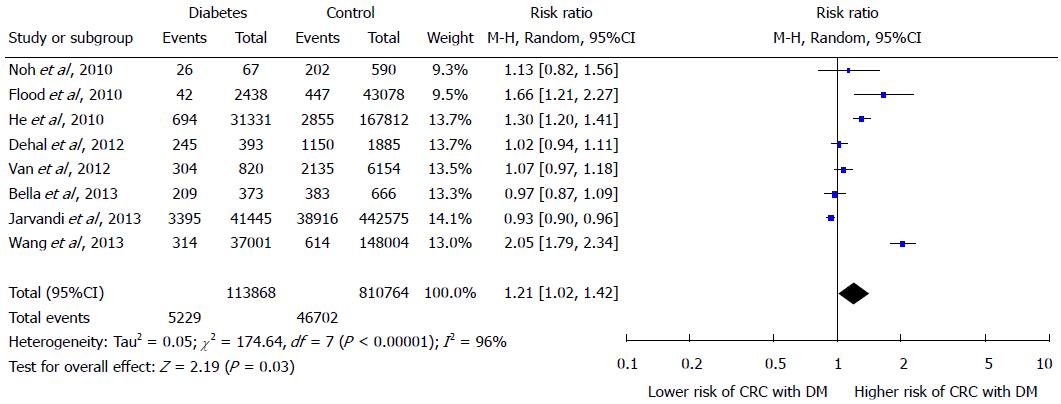

The Forest plot in Figure 2 portrays a series of estimates and their confidence intervals (CI) at 95% level. Each individual study’s effect size (outcome) is shown by a square and their CIs are represented through horizontal lines. The Forest plot shows that the selected studies have wider confidence interval and inconsistent response rates which indicates the heterogeneity. In order to check heterogeneity statistically, the Q test and I2 statistics were applied. The results of χ2 test in Figure 2 showed a 5% level of significance, thus rejecting the null hypothesis “all studies are identical”. The value of I2 is 96%, again verifying the presence of considerable heterogeneity amongst the studies. On the basis of considerable heterogeneity, random effects model was most appropriate for this study.

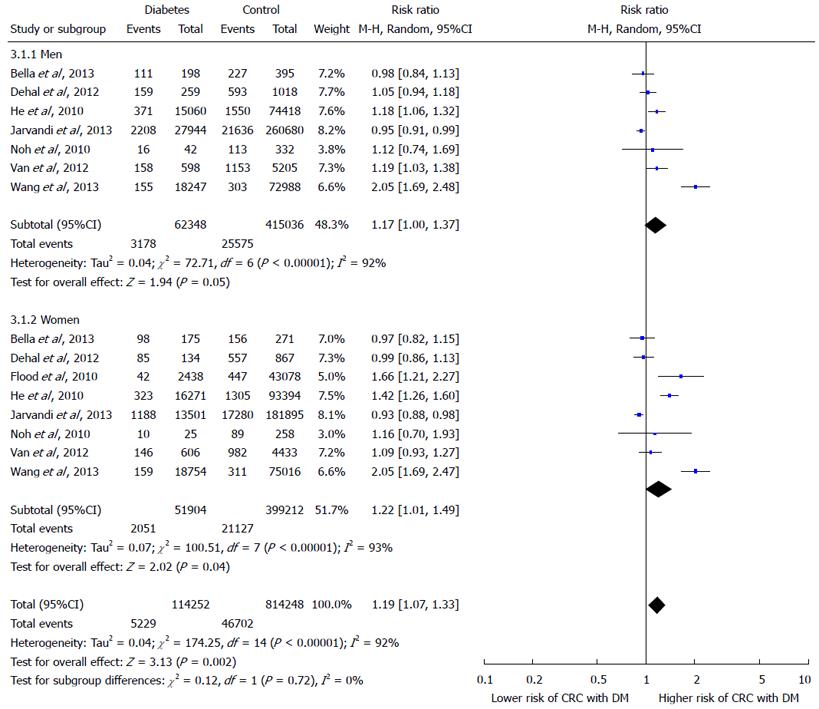

The effect summary which represents through diamond has RR of 1.21 (95%CI: 1.02-1.42) indicating positive relationship between DM and increased risk of CRC. There is great heterogeneity among all studies as only two studies have RR ratio below; Bella et al[15] has RR 0.97 and Jarvandi et al[16] has RR 0.93, while the remaining studies lie on the right side of one difference line showing positive association between DM and increased risk of CRC. The Z test is also significant at 5% level of significance and depicts significantly higher risk of CRC in diabetics by random-effects model. In Figure 3, Forest plot of gender sub groups shows the consistent results as majority of the studies favors the right side and has greater than 1 RRs. The effect summary RR of 1.19 with (95%CI: 1.07-1.33) favor a positive relationship between DM and increased risk of CRC with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 92% and P-value < 0.05). The Z test is significant at 5% level of significance for both sub groups showing significant risk of CRC with DM by random-effects model. Among both gender groups, women showed greater risk as their effect summary RR of 1.22 (95%CI: 1.01-49) with significant overall Z test at 5% level of significance was higher than the effect summary RR of 1.17 (95%CI: 1.00-1.37) of men showing insignificant Z test. However, both gender subgroups had considerable heterogeneity due to I2 of 92% and 93% for men and women, respectively (Figure 3).

The meta analysis showed a positive association of T2DM with the risk of CRC as shown by effect summary RR of 1.21 (95%CI: 1.02-1.42). Other studies have also demonstrated that CRC is more common in diabetics than in those without diabetes[7,17,18] and diabetic patients also have lower overall survival rates after CRC compared to non-diabetes, with 5-year survival of 35% and 48%, respectively[19,20].

A number of observational studies have described the association of T2DM with the risk of CRC[21-23]. A review of 97 prospective studies reported 123205 deaths among 820900 human subjects[24]. DM was associated with an increased risk of CRC (RR = 1.40; 95%CI: 1.20-1.63). Compared to people with fasting glucose levels < 5.6 mmol/L, the people with fasting glucose levels of 5.6-6.9 mmol/L had a 1.13-fold risk of death from any cancer. Participants with fasting glucose levels ≥ 7.0 mmol/L showed a 1.39-fold risk of death from any cancer. European population-based or occupational cohorts involved in the DECODE (Diabetes Epidemiology: Collaborative Analysis of Diagnostic Criteria in Europe) study showed a significant increase in deaths from CRC in men with DM and prediabetes[25]. A meta-analysis of 15 studies including more than 2.5 million patients found about 30% increased relative risk of developing CRC in diabetic compared to nondiabetic people[26]. A study exploring the histopathological differences in CRC between populations with and without diabetes showed that diabetics had deeper tumor invasion, more lymphovascular invasion, and greater TNM staging [OR (95%CI): 2.06 (1.37-3.10), 2.52 (1.74-3.63), and 2.45 (1.70-3.52), respectively; P < 0.001][27]. This finding underpins the aggressive nature of CRC growths in the diabetic patients and demands appropriate measures for better control of DM.

New onset of DM is invariably considered as a marker of occult cancer, or of progression of a known disease (reverse causality: diabetes is a consequence of cancer)[28]. The pathogenesis of DM in the development of CRC has been elucidated in the literature. Low Vitamin D level[29], obesity, sedentary lifestyle, and a high fat diet are reported to be associated with an increased risk of CRC[30]. Since abdominal obesity and physical inactivity are strong independent determinants of insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, and high levels of insulin may stimulate the growth of colorectal tumors, hyperinsulinemia was considered to mediate the effect of sedentary lifestyle on CRC risk. Hyperinsulinemia leads to CRC through a dose-dependent direct stimulation of cell growth and DNA synthesis in normal intestinal epithelial and CRC cells[31]. The intestinal endocrine L cells produce an incretin hormone, namely glucagon-like peptide-1, which stimulates insulin secretion in blood glucose dependent manner, pancreatic β cell proliferation and neogenesis[32]. Chronic hyperglycemia has been reported to induce an increasing production of reactive oxygen species, chronic oxidative stress[33], and marked activation of inflammatory pathways[34]. Inflammation is suggested to be one of the contributing mechanisms to the increased risk of cancerous growths[35].

The current meta-analysis showed that diabetic women had greater risk of CRC as their effect summary RR of 1.22 (95%CI: 1.01-49) with significant overall Z test at 5% level of significance was higher than the effect summary RR of 1.17 (95%CI: 1.00-1.37) of men. However, in their meta-analysis of 29 studies, Krämer et al[7] reported that overall estimates of RR were very similar amongst men (RR = 1.29; 95%CI: 1.19-1.140) and women (RR = 1.34; 95%CI: 1.22-1.47). Estimates of relative risk were very similar amongst men and women. Onitilo et al[36] examined the temporal relationship between CRC risk and DM using an electronic algorithm, clinical and lab data up to the onset of DM. The authors concluded that there was an increased risk of CRC in pre-diabetic men than women, and DM did not influence CRC risk in both genders after the clinical establishment of disease. In pre-diabetic men, CRC risk increased as time to DM onset decreased, indicating that the cumulative impacts of the pre-diabetes phase on colon cancer risk in men.

This meta-analysis has a limitation that the selected cohort studies might be prone to detection bias as the patients with diabetes are under continuous medical care, thus leading to high chances of CRC detection and early diagnosis.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis suggests that T2DM is associated with an increased risk of CRC. It is warranted to further investigate the underlying biological links between DM and CRC.

Author appreciates Mr. Bilal Sherif, research scholar Hailey College of Commerce, University of the Punjab, Lahore Pakistan for reviewing the statistical analysis and verifying results of this research.

As of 2010, more than 250 million people are suffering from type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) worldwide; and this number is expected to reach 380 million in 20 years.

This meta-analysis quantitatively assesses the results from published cohort studies to provide a more precise estimate of the association between T2DM as a possible predictor of the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC).

The effect summary RR of 1.19 with 95%CI of 1.07-1.33 indicate a positive relationship between DM and increased risk of CRC with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 92% and P-value < 0.05).

Very good piece of work - methodology well done systematic review performed well; language very good. Topic of the review is important and innovative.

P- Reviewer: Hussain A, Kawalec P, Xu HM S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Bao C, Yang X, Xu W, Luo H, Xu Z, Su C, Qi X. Diabetes mellitus and incidence and mortality of kidney cancer: a meta-analysis. J Diabetes Complications. 2013;27:357-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Inal A, Kaplan MA, Kucukoner M, Urakcı Z, Kılınc F, Isıkdogan A. Is diabetes mellitus a negative prognostic factor for the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer? Rev Port Pneumol. 2014;20:62-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McAuliffe JC, Christein JD. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and pancreatic cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2013;93:619-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sekikawa A, Fukui H, Maruo T, Tsumura T, Okabe Y, Osaki Y. Diabetes mellitus increases the risk of early gastric cancer development. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:2065-2071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shah MM, Erickson BK, Matin T, McGwin G, Martin JY, Daily LB, Pasko D, Haygood CW, Fauci JM, Leath CA. Diabetes mellitus and ovarian cancer: more complex than just increasing risk. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;135:273-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Xu H, Jiang HW, Ding GX, Zhang H, Zhang LM, Mao SH, Ding Q. Diabetes mellitus and prostate cancer risk of different grade or stage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99:241-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Krämer HU, Schöttker B, Raum E, Brenner H. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and colorectal cancer: meta-analysis on sex-specific differences. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1269-1282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chowdhury TA. Diabetes and cancer. QJM. 2010;103:905-915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Guraya SY, Almaramhy HH. Clinicopathological features and the outcome of surgical management for adenocarcinoma of the appendix. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;3:7-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8283] [Cited by in RCA: 8225] [Article Influence: 483.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jin T. Why diabetes patients are more prone to the development of colon cancer? Med Hypotheses. 2008;71:241-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zelenko Z, Gallagher EJ. Diabetes and cancer. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2014;43:167-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | RevMan. Review Manager (RevMan) is the software used for preparing and maintaining Cochrane Reviews [cited 2013 10th October]. Available from: http://tech.cochrane.org/revman. |

| 14. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39087] [Cited by in RCA: 46535] [Article Influence: 2115.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 15. | Bella F, Minicozzi P, Giacomin A, Crocetti E, Federico M, Ponz de Leon M, Fusco M, Tumino R, Mangone L, Giuliani O. Impact of diabetes on overall and cancer-specific mortality in colorectal cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:1303-1310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jarvandi S, Davidson NO, Schootman M. Increased risk of colorectal cancer in type 2 diabetes is independent of diet quality. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jiang Y, Ben Q, Shen H, Lu W, Zhang Y, Zhu J. Diabetes mellitus and incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26:863-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Deng L, Gui Z, Zhao L, Wang J, Shen L. Diabetes mellitus and the incidence of colorectal cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1576-1585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Barone BB, Yeh HC, Snyder CF, Peairs KS, Stein KB, Derr RL, Wolff AC, Brancati FL. Long-term all-cause mortality in cancer patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2754-2764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 697] [Cited by in RCA: 695] [Article Influence: 40.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | van de Poll-Franse LV, Haak HR, Coebergh JW, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Lemmens VE. Disease-specific mortality among stage I-III colorectal cancer patients with diabetes: a large population-based analysis. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2163-2172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Levi F, Pasche C, Lucchini F, La Vecchia C. Diabetes mellitus, family history, and colorectal cancer. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:479-480; author reply 480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Coughlin SS, Calle EE, Teras LR, Petrelli J, Thun MJ. Diabetes mellitus as a predictor of cancer mortality in a large cohort of US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1160-1167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 565] [Cited by in RCA: 592] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Green A, Jensen OM. Frequency of cancer among insulin-treated diabetic patients in Denmark. Diabetologia. 1985;28:128-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Seshasai SR, Kaptoge S, Thompson A, Di Angelantonio E, Gao P, Sarwar N, Whincup PH, Mukamal KJ, Gillum RF, Holme I. Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:829-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2142] [Cited by in RCA: 2022] [Article Influence: 144.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhou XH, Qiao Q, Zethelius B, Pyörälä K, Söderberg S, Pajak A, Stehouwer CD, Heine RJ, Jousilahti P, Ruotolo G. Diabetes, prediabetes and cancer mortality. Diabetologia. 2010;53:1867-1876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1679-1687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 719] [Cited by in RCA: 754] [Article Influence: 37.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sharma A, Ng H, Kumar A, Teli K, Randhawa J, Record J, Maroules M. Colorectal cancer: Histopathologic differences in tumor characteristics between patients with and without diabetes. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2014;13:54-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fedeli U, Zoppini G, Gennaro N, Saugo M. Diabetes and cancer mortality: A multifaceted association. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;106:e86-e89. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Guraya SY. Chemopreventive role of vitamin D in colorectal carcinoma. J Microsc Ultrast. 2014;2:1-6. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, Bergenstal RM, Gapstur SM, Habel LA, Pollak M, Regensteiner JG, Yee D. Diabetes and cancer: a consensus report. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:207-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 585] [Cited by in RCA: 685] [Article Influence: 45.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ahmed RL, Schmitz KH, Anderson KE, Rosamond WD, Folsom AR. The metabolic syndrome and risk of incident colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2006;107:28-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10002] [Cited by in RCA: 10453] [Article Influence: 696.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Robertson RP. Chronic oxidative stress as a central mechanism for glucose toxicity in pancreatic islet beta cells in diabetes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:42351-42354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 701] [Cited by in RCA: 738] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Lin Y, Berg AH, Iyengar P, Lam TK, Giacca A, Combs TP, Rajala MW, Du X, Rollman B, Li W. The hyperglycemia-induced inflammatory response in adipocytes: the role of reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4617-4626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 350] [Cited by in RCA: 378] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Rinaldi S, Rohrmann S, Jenab M, Biessy C, Sieri S, Palli D, Tumino R, Mattiello A, Vineis P, Nieters A. Glycosylated hemoglobin and risk of colorectal cancer in men and women, the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3108-3115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Onitilo AA, Berg RL, Engel JM, Glurich I, Stankowski RV, Williams G, Doi SA. Increased risk of colon cancer in men in the pre-diabetes phase. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |