Published online May 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.5950

Peer-review started: October 14, 2014

First decision: December 11, 2014

Revised: February 1, 2015

Accepted: February 5, 2015

Article in press: February 5, 2015

Published online: May 21, 2015

Processing time: 219 Days and 5.7 Hours

AIM: To determine the efficacy and safety of meticulous cannulation by needle-knife.

METHODS: Three needle-knife procedures were used to facilitate cannulation in cases when standard cannulation techniques failed. A total of 104 cannulations via the minor papilla attempted in 74 patients at our center between January 2008 and June 2014 were retrospectively reviewed.

RESULTS: Standard methods were successful in 79 cannulations. Of the 25 cannulations that could not be performed by standard methods, 19 were performed by needle-knife, while 17 (89.5%) were successful. Needle-knife use improved the success rate of cannulation [76.0%, 79/104 vs 92.3%, (79 + 17)/104; P = 0.001]. When the 6 cases not appropriate for needle-knife cannulation were excluded, the success rate was improved further (80.6%, 79/98 vs 98.0%, 96/98; P = 0.000). There were no significant differences in the rates of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography adverse events between the group using standard methods alone and the group using needle-knife after failure of standard methods (4.7% vs 10.5%, P = 0.301).

CONCLUSION: The needle-knife procedure may be an alternative method for improving the success rate of cannulation via the minor papilla, particularly when standard cannulation has failed.

Core tip: Cannulation of the minor papilla into the duct of Santorini can be difficult to achieve via standard procedures because of the tiny minor papilla orifice. Although various methods have been advocated to facilitate cannulation, some procedures still fail. The needle-knife has a slim tip, which is a unique advantage for insertion into the minor papilla orifice. After failure of standard cannulation techniques, we used three needle-knife procedures to facilitate cannulation via the minor papilla, which significantly improved the success rates of cannulation. In this series, we describe the meticulous procedures involved in this technique.

-

Citation: Wang W, Gong B, Jiang WS, Liu L, Bielike K, Xv B, Wu YL. Endoscopic treatment for pancreatic diseases: Needle-knife-guided cannulation

via the minor papilla. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(19): 5950-5960 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i19/5950.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.5950

Endoscopic treatment via the minor papilla may be the only option for some patients, including those with pancreatic divisum, recurrent acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis (CP) with severe abdominal pain, and pancreatographic changes[1-9]. The most important step in endoscopic treatment of these diseases is insertion of the guidewire into the duct of Santorini[10-12]. Standard procedures involve wire-guided cannulation with a standard sphincterotome (5-7F cannula) that has a straight or tapered tip that can accept a 0.035-inch guidewire[11,13]. However, it is often difficult to cannulate the minor papilla.

Experts have advocated various procedures to facilitate minor papilla cannulation, including spraying the minor papilla with methylene blue and indigo carmine to help identify the orifice[11,14], administering intravenous secretin to induce flow of pancreatic secretions and to make the minor papilla orifice more evident[5,10,15,16], using a needle-knife to perform minor papilla fistulotomy[4], using tapered catheters or sphincterotomes with or without a small-caliber wire[1-5,7-10,14-21], and performing rendezvous techniques, wire-guided cannulation, or physician-controlled wire-guided cannulation[4,16,21,22]. These procedures produced successful cannulation in 73% to 100% of documented cases (i.e., 0% to 27% of procedures failed; Table 1)[1-5,7-11,14-22].

| Ref. | Year | No. | Cannulation procedure | Success (%) | Complication (%) |

| 18 | 1984 | 6 | Blunt tipped needle catheter | 83.3 | 0 |

| 1 | 1986 | 6 | Flexible Seldinger wire with a dilator and papillotome | 100 | 0 |

| 19 | 1987 | 18 | Needle-tipped catheter or 0.018 inch guidewire | 72.9 | 4.2 |

| 11 | 1990 | 136 | Tapered or needle-tipped catheter + secretin (35% patients) | 91 | 1.5 |

| 20 | 1992 | 19 | Tapered catheter with 0.018 inch guidewire | 83 | NA |

| 2 | 2000 | 25 | Tapered catheter with 0.018 or 0.02 inch guidewire | 73.5 | 0 |

| 3 | 2002 | 24 | Tapered catheter with 0.018 inch guidewire | NA | 38 |

| 23 | 2003 | 6 | Contour catheter with 0.025 or 0.035 inch wire (rendezvous technique) | 100 | 0 |

| 15 | 2003 | 14 | Methylene blue + needle tipped catheter with 0.018 inch guidewire | 85.7 | 7.1 |

| 16 | 2003 | 28 | Synthetic porcine secretin | 89.3 | 0 |

| 4 | 2004 | 11 | Catheter with 0.025 inch guidewire (including rendezvous technique), needle-knife to minor papilla fistulotomy | 90.9 | 0 |

| 21 | 2006 | 184 | Tapered or metal tip catheter with 0.018 or 0.025 inch guidewire | NA | 8.2 |

| 6 | 2008 | 57 | Tapered cannula with a guidewire + secretin (10% patients) | 86 | 11.7 |

| 17 | 2009 | 64 | Pull-sphincterotome with 0.018-0.035 inch guidewire (wire-guided cannulation) + secretin (17% patients) | 85 | 26.5 |

| 22 | 2010 | 25 | Tip sphincterotome with a 0.025 inch guidewire (physician-controlled wire-guided cannulation) | 96 | 12 |

| 8 | 2013 | 34 | Tapered catheter with or without 0.025 inch guidewire | 80 | 4.5 |

| 9 | 2013 | 48 | Tapered cannula and a 0.025 or 0.035 inch guidewire | 97.9 | 2.0 |

| 10 | 2013 | 45 | Tapered-tip or needle-tip catheters, short-nose pull-sphincterotomes, and 0.018-0.035 inch guidewires | 91.9 | 16.1 |

The main reason for cannulation failure is that the minor papilla orifice can be inconspicuous or appear as a tiny dimple or papule, with almost no elevation or apparent orifice, and so guidewires and sphincterotome cannulas are larger than the minor papilla orifice. Although smaller-caliber guidewires (e.g., 0.018- to 0.025-inch) are available, they are soft and difficult to control. Furthermore, intravenous secretin is contraindicated in children/adolescents, cases of acute pancreatitis, patients who have used anticholinergic medications within one week of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), patients with known hypersensitivity or adverse reactions to secretin, and patients who are pregnant or breastfeeding[15]. Thus, further innovations are needed to improve success rates and minimize the adverse events of these techniques.

The needle-knife has a slim tip, which is a unique advantage for insertion into the minor papilla orifice. Many centers have used needle-knife-guided cannulation via the minor papilla. However, some centers have discontinued using the technique, which has mainly been assessed for therapeutic potential[5,9,13,16,20]. Since 2008, our center has used needle-knives for cannulation when the minor papilla orifice is too small to allow a catheter or guidewire to advance deeply. The objective of this study was to describe the efficacy and safety of this meticulous procedure.

The ERCP database was retrospectively reviewed to find all patients who underwent cannulation via the minor papilla at the Digestive Endoscopy Center at Ruijin Hospital from January 2008 to June 2014. Patients who did not receive cannulation via the minor papilla were excluded. After approval by the Institutional Review Board, medical records were accessed and the following data were acquired for each patient: age, sex, presenting problem, number and success of procedures, diagnostic findings, therapeutic measures, cannulation time, adverse events, patient management, and follow-up visits and management.

“Successful cannulation” was defined as deep placement of the guidewire into the duct of Santorini (i.e., the dorsal duct), which was assessed by the injection of contrast medium[13]. “Cannulation time” was defined as the elapsed time from the commencement of cannulation attempts to the successful cannulation of the duct of Santorini[15]. “Cannulation attempt” was defined as contact between the cannulating device and the papilla for at least 5 s[23]. Because few centers use a needle-knife to introduce a guidewire via the minor papilla during cannulation, we referred to previous studies that used the needle-knife for difficult biliary cannulation[13,24-27] and our past experiences. We arbitrarily defined “unsuccessful cannulation” as “a skilled endoscopist not achieving cannulation after 5 min or more than 15 attempts”.

Pancreatic divisum was diagnosed via the presence or absence of ductal abnormalities by ERCP[10]. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) was diagnosed from ERCP data or histologic examination[28]. Similar to Li and Wang et al[29], Wang currently at Ruijin Hospital North, CP was diagnosed on the basis of abdominal pain and the presence of any of the following findings: (1) ductal changes on ERCP, (2) pancreatic calcification (including ductal stones) revealed by imaging, and (3) histological analyses (when surgical intervention was performed).

Major adverse events of ERCP were defined according to consensus criteria. Post-ERCP pancreatitis was defined as new or worsened abdominal pain for more than 24 h after endoscopy, with amylase levels more than threefold the normal upper limit, which required hospitalization or prolonged planned hospitalization for at least one night. Mild infection (cholangitis) was defined as a temperature of more than 38 °C for 24 to 48 h after the procedure, accompanied by colicky pain and cholestasis/jaundice without evidence of unrelated infections. “Moderate bleeding” was defined as bleeding requiring the maximum number of transfusions (4 units of packed cells) in the absence of angiographic or surgical intervention[29,30].

The risks and benefits of the procedure and alternative treatments were explained. Written informed consent was obtained from adult patients and parents/guardians of children before the procedure. Patients were mildly sedated (with diazepam, meperidine, and scopolamine butylbromide) or deeply sedated (with propofol injection, fentanyl, and vecuronium bromide) by anesthetists. Side-viewing duodenoscopes (JF-240 for children and adolescents, JF-260 for adult patients; Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were used, and cannulation was performed with standard pull-sphincterotomes (ENDO-FLEX, Germany) with or without a guidewire (Jagwire; 0.025- or 0.035-inch in diameter, 450-cm in length; Boston Scientific).

When endoscopists detected pancreatic divisum, distortion of the duct of Wirsung, a tight stricture, or an impacted stone downstream from the junction of the main and accessory ducts, cannulation via the minor papilla was attempted and a two-step sequence guideline was followed. The direct approach via the minor papilla was attempted by wire-guided cannulation with a standard sphincterotome (physician-controlled wire-guided cannulation) or directly using the tapered tip of the sphincterotome (Step 1). When the main pancreatic duct was distorted and a guidewire introduced via the major papilla entered the duodenum via the minor papilla, the “rendezvous method” was performed (Step 1.1). A guidewire was inserted into the duct of Wirsung via the major papilla, and then into the duodenum via the duct of Santorini and minor papilla. The guidewire was grasped and removed through the biopsy channel of the endoscope[5,22].

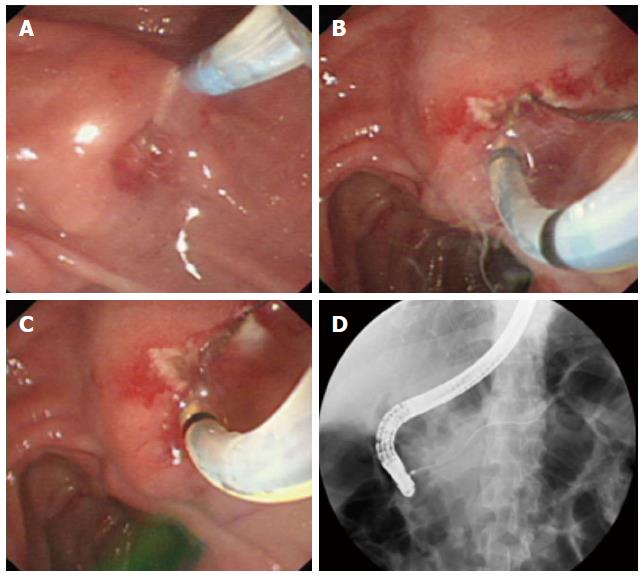

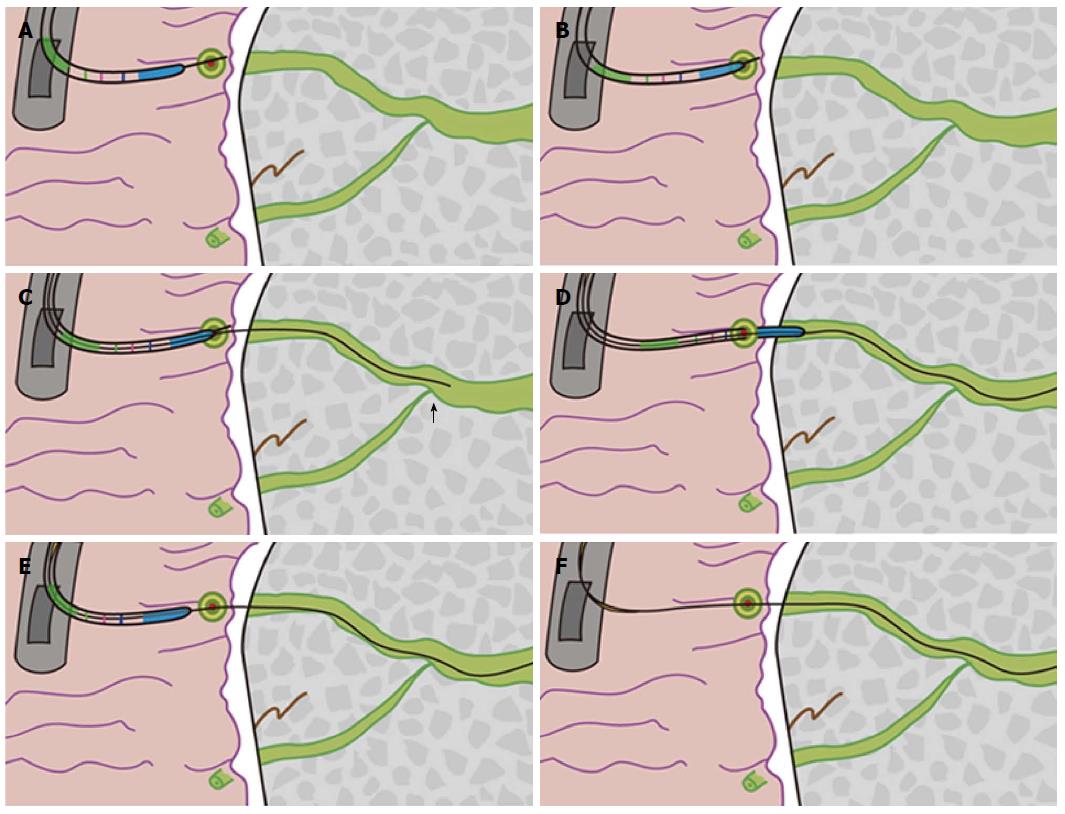

A needle-knife (MicroKnife TM XL, Boston Scientific, USA) was used for cannulation when the pull-sphincterotome failed, when the minor papilla orifice was too small to receive the pull-sphincterotome or guidewire, or when the expert (Gong B) deemed it necessary (Step 2). For needle-knife cannulation, the needle tip was extended 5 to 7 mm beyond the cannula tip and passed in the direction of the minor papilla orifice. If the orifice was visible, then a small incision was made by the needle-knife (precut papillotomy; Step 2.1). The incision was started at the top of the papillary orifice (12 o’clock position) and extended in the cephalad direction until the papillary mound was divided or the incision was sufficiently large to receive the tip of the guidewire or pull-sphincterotome. The cut size was determined by the size of the minor papilla, and generally ranged from 3 to 6 mm. After the incision was made, the needle-knife was exchanged for a pull-sphincterotome with a guidewire, which was carefully advanced into the duct of Santorini. This procedure was named “needle-knife papillotomy with introduction of a guidewire and pull-sphincterotome” (NPI-GS; Figure 1). If the incision in the minor papilla orifice was too small to receive a guidewire, then the sphincterotome was used to perform a small papillotomy (Step 2.1.1). This procedure was named “needle-knife papillotomy with introduction of a guidewire, pull-sphincterotome, and guidewire” (NPI-GSG) (Figure 2).

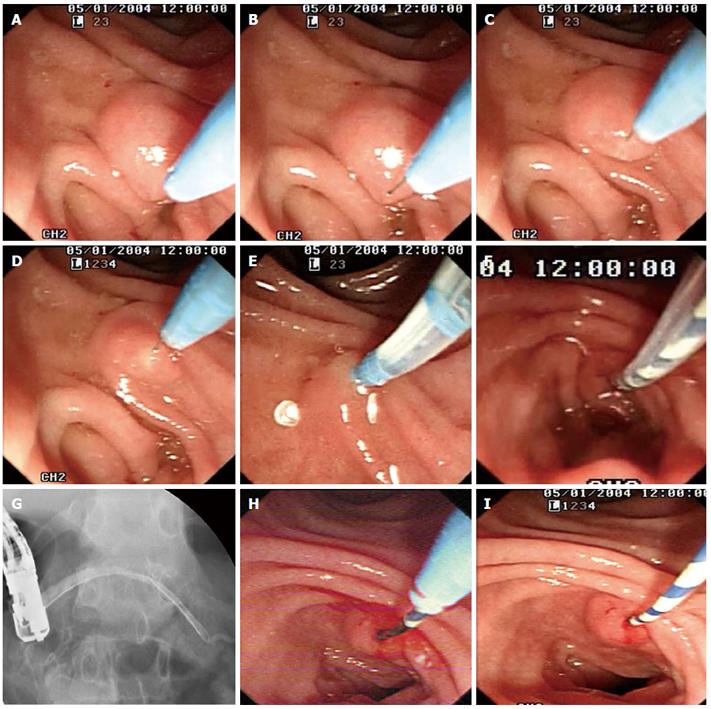

When the minor papilla orifice was invisible, we used the “needle-knife introduction of a guidewire” (NI-G) procedure (Step 2.2). The needle tip was aimed at and carefully inserted into the orifice. The needle-knife cannula was pushed forward, while the needle-knife tip was pulled back until the cannula anastomosed with the minor papilla orifice. The needle-knife cannula was lightly pressed on or adjacent to the minor papilla orifice while the needle-knife tip was in the orifice. A guidewire (Jagwire; 0.025- or 0.035-inch in diameter, 450-cm in length; Boston Scientific) was carefully advanced approximately 25 mm into the duct of Santorini through the needle-knife cannula and the minor papilla orifice until it passed the cross-point of the ducts of Wirsung and Santorini. The needle-knife cannula was inserted into the capitular head of the duct of Santorini along the guidewire and contrast medium was injected. After the course of the duct of Santorini was confirmed, the guidewire was advanced deeply into the duct for therapeutic intervention, while the needle-knife cannula was pulled back until it was completely withdrawn. Finally, the needle-knife was removed, leaving the guidewire in place (Figures 3-5).

After successful cannulation via the minor papilla and the duct of Santorini, endoscopic interventions were performed. These interventions included papillotomy, stone extraction, nasopancreatic drainage, stricture dilation, stent insertion, and stent retrieval.

Eligible patients were contacted, with follow-up information obtained by Jiang WS. A questionnaire was completed via telephone interviews or face-to-face meetings with patients. The scripted telephone questionnaire included questions regarding the present condition of the patient. Answers were provided on a 5-point Likert scale: 1, cured; 2, better; 3, same; 4, worse; and 5, much worse. Data regarding any repeat ERCP, surgery, and narcotic requirements were collected[6]. The follow-up period was defined as the period between the date of the first endoscopic intervention at our hospital to the last follow-up[30], date of death, or date of surgical intervention.

Quantitative data were summarized by mean ± SD or median (range). Data were analyzed by t-tests (for normal distributions) or by Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (for non-normal distributions). Categorical data were presented as frequencies (percentages) and analyzed by χ2 tests with or without the Yates correction for continuity or the Fisher exact test, where appropriate. SPSS 17.7 software for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analyses. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant[30].

A total of 5385 ERCPs were performed, and 104 cannulations (1.9%) via the minor papilla were attempted in 74 patients (mean: 1.4 ERCPs/patient; range: 1-5 ERCPs/patient). Diagnoses and clinical indications for the procedures are presented in Table 2. Three patients with pancreatic divisum and CP also received surgical interventions (post-pancreaticojejunostomy, n = 1; Billroth I reconstruction after gastrectomy, n = 1; Billroth II reconstruction after gastrectomy, n = 1).

| Basic clinical data | n |

| Total number of patients | 74 |

| Patients that received therapeutic ERCP | 70 |

| Patients that received diagnostic ERCP | 4 |

| Total cannulation procedures via minor papilla | 104 |

| Only using standard method1 | 79 (56 cases) |

| Using needle-knife after failure of standard method Using needle-knife at start and standard methods later2 | 14 (14 cases) 11 (4 cases)3 |

| Age (yr) | 40.5 ± 21.8 |

| Children and adolescents (age < 18 yr) (female) | 16 (11) |

| Adults (female) | 58 (22) |

| Clinical indications for cannulation procedures | |

| Pancreatitis | 33 |

| Chronic recurrent pancreatic-type pain without enzyme elevation | 37 |

| Biliary disease | 2 |

| Definite or suspected pancreatic mass | 2 |

| Diagnoses | |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 13 |

| Pancreas divisum | 17 |

| Chronic pancreatitis and pancreas divisum | 40 |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms | 4 |

| Follow-up | |

| Patients who received therapeutic ERCP | 70 |

| Patients who received therapeutic ERCP and were followed up | 67 (95.7%) |

| Follow-up period (months) | 29.0 ± 22.2 |

| Follow-up results4 | |

| Improved | 49 |

| Cured | 3 |

| Same | 7 |

| Worse or much worse | 5 |

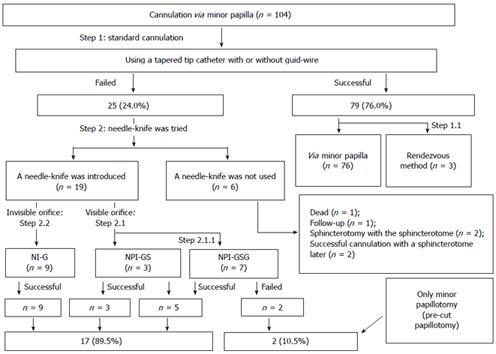

Cannulations using sphincterotomes with or without guidewires were successful in 79/104 ERCPs (76.0%). Among the 25 failed cannulations performed with sphincterotomes, 19 cannulations with needle-knives were performed. Seventeen of these procedures (89.5%, 17/19) were successful. One of the 2 patients who underwent failed procedures with needle-knife (i.e., only performed precut papillotomy) reported improvement; the other patient reported unchanged symptoms. In the remaining 6 cases, the needle-knife was not used because other diagnoses were discovered that dictated the use of other procedures. Thus, the success rate of minor papilla cannulation improved significantly with the needle-knife procedure [76.0%, 79/104 vs 92.3%, (79 + 17)/104; P = 0.001]. Excluding the 6 cases that were not appropriate for needle-knife cannulation, the success rate was improved even further (80.6%; 79/98 vs 98.0%; 96/98, P = 0.000; Figure 5).

The overall incidence of post-ERCP adverse events was 5.8% (6/104). Adverse events included post-ERCP pancreatitis (mild, n = 1; moderate, n = 2; severe, n = 1), mild infection (n = 1), and moderate bleeding (n = 1). There were no ERCP-related perforations or deaths. There were no significant differences in the rates of post-ERCP adverse events between the group using a sphincterotome alone and the group using a needle-knife after sphincterotome failure (4.7% vs 10.5%, P = 0.301; Table 3).

| Sphincterotome1 (n = 85) | Needle-knife2 (n = 19) | P value | |

| ERCP procedures in female cases | 32 (37.7) | 11 (57.9) | 0.105 |

| Minor papilla sphincterotomy | 493 (57.7) | 10 (52.6) | 0.690 |

| Dilation | 25 (30.5) | 4 (21.1) | 0.578 |

| Stents | 53 (61.0) | 11 (57.9) | 0.796 |

| ENPD tubes | 21 (24.7) | 4 (21.5) | 1.000 |

| Stents + ENPD tubes | 74 (87.1) | 15 (79.0) | 0.468 |

| Stone extraction and clearance of Santorini’s duct | 18 (21.2) | 2 (10.5) | 0.355 |

| Retrieving of migrated duct stents | 1 | 1 | - |

| Recorded cannulation time (min)4 | 5.5 ± 4.0 | 7.3 ± 5.1 | 0.5053 |

| Post-ERCP complications | 4 (4.7) | 2 (10.5) | 0.301 |

The needle-knife was used 5 times in 4 children/adolescents (25.0%, 4/16) and 14 times in 14 adult cases (24.1%, 14/58) (P = 1.000). There were no significant differences in the rates of stent insertions, cannulation failures, post-ERCP adverse events, and needle-knife use between children/adolescents and adults (Table 4). Needle-knife cannulations were performed in 10 female patients (52.6%, 10/19), while sphincterotome cannulation was performed in 23 female patients (42.6%, 23/55) (P = 0.450). Cannulation procedures with the needle-knife after failed cannulation with the sphincterotome were slightly more common in female patients (P = 0.105; Table 3). However, the incidence of post-ERCP adverse events (4.9%; 3/61) in male cases was similar to female cases (7.0%; 3/43) (P = 0.689).

| Adolescents1(n = 30) | Adults(n = 74) | P value | |

| Cannulation with needle-knife | 5 (16.7) | 14 (18.9) | 0.788 |

| Stents | 20 (66.7) | 44 (59.5) | 0.494 |

| Cannulation failure | 2 (6.7) | 6 (8.1) | 1.000 |

| Post-ERCP complication | 2 (6.7) | 4 (5.4) | 1.000 |

Only 3 of the 70 patients who received therapeutic ERCPs were lost to follow-up. Among the 67 (95.7%) patients with follow-up information, 3 patients with CP (n = 1) or CP and pancreas divisum (n = 2) developed pancreatic cancer and died. Improvements (better and cured) were documented in 52 (77.6%) patients. Excluding the 3 patients with pancreatic cancer, the overall rate of improvement was 81.3% (52/64) (Table 2, Figure 5).

For cannulation, one size does not fit all[12]. The duration of attempted cannulation varies, and procedures and instruments should be tailored to the risk profile and papillary/ductal anatomy of each patient[12]. Five different cannulation procedures were performed in this study, including 2 procedures with the pull-sphincterotome (physician-controlled wire-guided cannulation or directly using the tapered tip of the sphincterotome and rendezvous method) and 3 procedures with the needle-knife (NI-G, NPI-GS, and NPI-GSG procedures). Use of the needle-knife for cannulation was determined in each case without regard for age or gender.

To the best of our knowledge, the NI-G procedure may be a novel needle-knife procedure. The needle tip was only used to grasp the minor papilla orifice and, subsequently, a guidewire was carefully advanced into the duct of Santorini through the needle-knife cannula. Papillotomy was not performed during the NI-G procedure. Literature searches revealed one study somewhat similar to ours, in which Song et al[4] used needle-knives to perform minor papilla fistulotomies in 3 patients with CP. Another study, reported by Wilcox et al[31], performed a precut papillotomy when a tapered-tip catheter could not be passed into the dorsal duct over a guidewire (i.e., partly successful cannulation).

Given that the orientation of the sphincterotome to the desired duct is favorable and adjustable compared to a catheter, we preferred to use a tapered tip catheter of a standard pull-sphincterotome with or without a guidewire to cannulate via the minor papilla, consistent with many endoscopists[4,5,7-10,14-22]. The rate (76.0%) of successful cannulations when standard procedures were used was slightly lower than the results presented in previous studies. This difference may be because our study included some children and adolescents, some patients with definite or suspected pancreatic masses, and some patients who had received surgical interventions. Cannulations in these cases are generally considered to be more difficult.

The total success rate for cannulation in our study, including cannulation by needle-knife, was 92.3%. When we excluded the 6 patients who were not indicated for cannulation by needle-knife, the success rate reached 98.0% (P = 0.000). The success rate of cannulation procedures performed by needle-knife after failure with the sphincterotome still reached 89.5% (17/19). Importantly, our success rates and patient numbers are higher, and the incidence (5.8%) of post-ERCP adverse events was lower, compared to previous studies. Cannulation with the needle-knife, use of stents, age, and gender did not correlate with adverse events. At the end of follow-up, 81.3% of patients reported improvement, similar to previously reported results (range: 58%-96%).

The small or inconspicuous minor papilla orifice often makes it difficult to use a pull-type sphincterotome, guidewire, or catheter[1,11]. As seen through a duodenoscope, the small minor papilla orifice appears like a “point”, whereas the cross-sections of the guidewire, sphincterotome cannula, and catheter tip are like “faces”. Because of the size differences and peristalsis of the duodenum, it is difficult to produce anastomoses between these “faces” and “points”, especially when the neck or waist behind the “face” is very soft. However, the cross-section of the tiny needle-knife tip is similar to a point, enabling aligning of the point of the needle-knife tip with the “point” of the minor papilla orifice. Thus, using a needle-knife to guide cannulation via the minor papilla may be a suitable choice.

When cannulation with a pull-sphincterotome fails, the needle-knife can be used in 2 distinct ways. First, it can be directly inserted into the small orifice of the minor papilla. This procedure is relatively easy to perform, because the orifice and needle are similar in size, and a “point-to-point” connection can be made. Alternatively, if the orifice is visible, then the needle-knife can be used to introduce a small incision or perform a papillotomy (precut papillotomy), thereby turning the minor papilla orifice into a “face”. This procedure expands the minor papilla orifice and enables insertion of a guidewire, whose cross-section is also like a “face” (i.e., the NPI-GS procedure). This procedure is also easy to perform, because a “face-to-face” connection can be made with the expanded orifice. If the orifice is still too small to receive a guidewire smoothly, then a small papillotomy can be performed by using the pull-sphincterotome to expand the orifice further (i.e., the NPI-GSG procedure). When the orifice is too small to make an incision with the needle-knife, the NI-G procedure can be used.

Some details of the NI-G cannulation procedure must be emphasized: (1) “point-to-point” indicates that the tip of needle should be aimed at and inserted or aligned adjacent to the minor papilla orifice. When the orifice was too small to distinguish, we tried to insert the needle in the general direction of the orifice; (2) duodenal peristalsis often made it very difficult to cannulate and aim the tip of the pull-sphincterotome at the orifice. During the NI-G procedure, the sphincter was inserted into the needle tip to provide structural support and anchor the needle-knife in the orifice. This fixation step facilitated the aiming of the needle-knife cannula at the minor papilla orifice, resulting in a smooth passage that directed the guidewire into the duct of Santorini; (3) the center of effort is located at the orifice. After the needle-knife tip was inserted into the minor papilla orifice, the needle-knife was anchored in the orifice to increase control over cannulation, similar to standard sphincterotomes; (4) after the needle-knife tip was inserted into the orifice, the needle-knife cannula was pushed forward while the needle-knife tip was pulled back until the cannula anastomosed with the orifice. When the needle-knife cannula is pushed forward, the needle must be pulled back at the same rate, so that the inserting needle tip remains in place and does not follow the cannula to be completely withdrawn; and (5) if the NI-GSG procedure fails, then the NI-G procedure does not need to be performed. Failure of the NI-GSG procedure often indicates that the duct of Santorini is too narrow to receive a guidewire.

Safety is a major concern with needle-knife procedures. Adverse events, including bleeding, retroperitoneal perforation, and (especially) pancreatitis have been reported. In this study, needle-knife cannulation was performed through meticulous procedures with the following considerations: (1) the needle-knife procedures did not always involve minor papillotomy, which are associated with an increased risk of post-ERCP adverse events, especially bleeding and perforation. Of the 19 cannulations performed by needle-knife, 9 (47.4%) NI-G procedures did not involve minor papillotomy; (2) minor papillotomy (precut papillotomy; NPI-GS and NPI-GSG procedures) was used to expand the minor papilla orifice to facilitate guidewire or sphincterotome insertion into the duct of Santorini. Although the maximum extent of each cut was determined by the minor papilla size, the cut was stopped as soon as the incision received the tip of the guidewire or pull-sphincterotome, especially if the practitioner was concerned about bleeding or perforation. If an incision created by the needle-knife was insufficiently large, then the pull-sphincterotome was used to enlarge it; (3) the needle-knife was used before insertion of a guidewire or stent for cannulation. Minor papillotomy was not performed along guidewires or stents, as has been the case in other studies[5,16,20]. The needle-knife was used to accomplish cannulation via the minor papilla, and was not used as a therapeutic procedure; (4) seven or more transpapillary cannulation attempts or more than five cannulations of the pancreatic duct have been identified as independent risk factors for post-ERCP adverse events. Compared to late precuts, early precut implementation reduces the risk of pancreatitis. Many endoscopists consider the number of attempts at the papilla (i.e., prolonged cannulation attempts, varying from 5 to 20 min) as an independent risk factor for pancreatitis. Therefore, using the needle-knife to cannulate quickly may be safer than repeated attempts with a sphincterotome, which are likely to fail[13,24-28]; and (5) a skilled assistant worked alongside the endoscopist during these procedures, helping the endoscopist to maintain control over the endoscope and needle-knife. The cannulation times were similar between the needle-knife and the sphincterotome (P = 0.505).

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, the data used in this study were retrospective and nonrandom, which may have introduced unintentional bias in group selection. The search strategies employed were diligent, although some patient information was not directly collected in a standardized manner in the clinic[21]. However, study subjects were identified from clinical information recorded in a computerized database system, and some patient follow-ups were conducted by telephone after hospital discharge. Thus, the data were as complete and reliable as possible. Second, the number of recorded cannulation times was small compared to the total number of procedures performed, with most measurements being made after 2010. All cannulations using the needle-knife were performed or supervised by one expert (Gong B), but not all cannulations using the sphincterotome were supervised. These factors may introduce bias in comparing cannulation times, but the use of the needle-knife for cannulation via the minor papilla was exploratory. Cannulation times including procedural consultations may only approximate the true time of cannulation. The data showed that cannulation time using a needle-knife was no longer than when using a sphincterotome. Finally, the small number of patients included in this study may overestimate or underestimate the rates of success and adverse events. Studies with larger numbers of patients are needed to verify our results.

In summary, needle-knife cannulation via the minor papilla confers important technical advantages when compared to procedures using sphincterotomes with or without guidewires. Needle-knife cannulation is a safe procedure, but should be performed meticulously. Needle-knife procedures should be included in routine practice to improve the success rates of cannulation via the minor papilla, particularly when standard cannulation procedures have failed.

Endoscopic treatment via the minor papilla may be the only possible treatment option for some patients. However, owing to its tiny size, the minor papilla orifice is often difficult to cannulate.

Despite the development of various procedures to facilitate minor papilla cannulation, some cannulation procedures still fail. The slim tip of the needle-knife offers a unique advantage for its insertion into the minor papilla orifice. However, the needle-knife has been utilized in many centers only as a therapeutic procedure, and its use has been discontinued in cannulation procedures via the minor papilla.

Three procedures with the needle-knife were performed to cannulate the minor papilla after standard cannulation techniques had failed. These procedures significantly improved the success rate of cannulation. The study demonstrates the first use of the “needle-knife introduction of a guidewire (NI-G)” procedure, in which the needle tip was only used to grasp the minor papilla orifice and papillotomy was not performed.

Needle-knife procedures should be included in routine practice to improve the success rate of cannulation via the minor papilla, particularly when standard cannulation procedures have failed.

NI-G: Needle-knife introduction of a guidewire. NPI-GS: Needle-knife papillotomy with introduction of a guidewire and pull-sphincterotome. NPI-GSG: Needle-knife papillotomy with introduction of a guidewire, pull-sphincterotome, and guidewire

The authors describe three meticulous procedures with the needle-knife to cannulate the minor papilla. This study describes the procedures appropriately and is relevant to clinicians.

P- Reviewer: Garcia-Cano J S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Rutherford A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Soehendra N, Kempeneers I, Nam VC, Grimm H. Endoscopic dilatation and papillotomy of the accessory papilla and internal drainage in pancreas divisum. Endoscopy. 1986;18:129-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ertan A. Long-term results after endoscopic pancreatic stent placement without pancreatic papillotomy in acute recurrent pancreatitis due to pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:9-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Heyries L, Barthet M, Delvasto C, Zamora C, Bernard JP, Sahel J. Long-term results of endoscopic management of pancreas divisum with recurrent acute pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:376-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Song MH, Kim MH, Lee SK, Lee SS, Han J, Seo DW, Min YI, Lee DK. Endoscopic minor papilla interventions in patients without pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:901-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chacko LN, Chen YK, Shah RJ. Clinical outcomes and nonendoscopic interventions after minor papilla endotherapy in patients with symptomatic pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:667-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Borak GD, Romagnuolo J, Alsolaiman M, Holt EW, Cotton PB. Long-term clinical outcomes after endoscopic minor papilla therapy in symptomatic patients with pancreas divisum. Pancreas. 2009;38:903-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fujimori N, Igarashi H, Asou A, Kawabe K, Lee L, Oono T, Nakamura T, Niina Y, Hijioka M, Uchida M. Endoscopic approach through the minor papilla for the management of pancreatic diseases. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:81-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bhasin DK, Rana SS, Sidhu RS, Nagi B, Thapa BR, Poddar U, Gupta R, Sinha SK, Singh K. Clinical presentation and outcome of endoscopic therapy in patients with symptomatic chronic pancreatitis associated with pancreas divisum. JOP. 2013;14:50-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rustagi T, Golioto M. Diagnosis and therapy of pancreas divisum by ERCP: a single center experience. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:93-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Benage D, McHenry R, Hawes RH, O’Connor KW, Lehman GA. Minor papilla cannulation and dorsal ductography in pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:553-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Freeman ML, Guda NM. ERCP cannulation: a review of reported techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:112-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Freeman ML. Cannulation techniques for ERCP: one size does not fit all. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:132-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Coelho-Prabhu N, Dzeletovic I, Baron TH. Outcome of access sphincterotomy using a needle knife converted from a standard biliary sphincterotome. Endoscopy. 2012;44:711-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Park SH, de Bellis M, McHenry L, Fogel EL, Lazzell L, Bucksot L, Sherman S, Lehman GA. Use of methylene blue to identify the minor papilla or its orifice in patients with pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:358-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Devereaux BM, Fein S, Purich E, Trout JR, Lehman GA, Fogel EL, Phillips S, Etemad R, Jowell P, Toskes PP. A new synthetic porcine secretin for facilitation of cannulation of the dorsal pancreatic duct at ERCP in patients with pancreas divisum: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind comparative study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:643-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Maple JT, Keswani RN, Edmundowicz SA, Jonnalagadda S, Azar RR. Wire-assisted access sphincterotomy of the minor papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:47-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schleinitz PF, Katon RM. Blunt tipped needle catheter for cannulation of the minor papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 1984;30:263-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | McCarthy J, Fumo D, Geenen JE. Pancreas divisum: a new method for cannulating the accessory papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 1987;33:440-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lans JI, Geenen JE, Johanson JF, Hogan WJ. Endoscopic therapy in patients with pancreas divisum and acute pancreatitis: a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:430-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Attwell A, Borak G, Hawes R, Cotton P, Romagnuolo J. Endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy for pancreas divisum by using a needle-knife or standard pull-type technique: safety and reintervention rates. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:705-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Maple JT, Mansour L, Ammar T, Ansstas M, Coté GA, Azar RR. Physician-controlled wire-guided cannulation of the minor papilla. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2010;2010:629308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Catalano MF, Bukeirat FA, Geenen JE. Difficult cannulation of the minor papilla in patients presenting with incomplete pancreas divisum: a new rendezvous technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:AB207. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Kubota K, Sato T, Kato S, Watanabe S, Hosono K, Kobayashi N, Hisatomi K, Matsuhashi N, Nakajima A. Needle-knife precut papillotomy with a small incision over a pancreatic stent improves the success rate and reduces the complication rate in difficult biliary cannulations. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:382-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Tang SJ, Haber GB, Kortan P, Zanati S, Cirocco M, Ennis M, Elfant A, Scheider D, Ter H, Dorais J. Precut papillotomy versus persistence in difficult biliary cannulation: a prospective randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2005;37:58-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | de Weerth A, Seitz U, Zhong Y, Groth S, Omar S, Papageorgiou C, Bohnacker S, Seewald S, Seifert H, Binmoeller KF. Primary precutting versus conventional over-the-wire sphincterotomy for bile duct access: a prospective randomized study. Endoscopy. 2006;38:1235-1240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cennamo V, Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Eusebi LH, Ceroni L, Laterza L, Fabbri C, Bazzoli F. Can early precut implementation reduce endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related complication risk? Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Endoscopy. 2010;42:381-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | López A, Ferrer I, Villagrasa RA, Ortiz I, Maroto N, Montón C, Hinojosa J, Moreno-Osset E. A new guidewire cannulation technique in ERCP: successful deep biliary access with triple-lumen sphincterotome and guidewire controlled by the endoscopist. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1876-1882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Talamini G, Zamboni G, Salvia R, Capelli P, Sartori N, Casetti L, Bovo P, Vaona B, Falconi M, Bassi C. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2006;6:626-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Li ZS, Wang W, Liao Z, Zou DW, Jin ZD, Chen J, Wu RP, Liu F, Wang LW, Shi XG. A long-term follow-up study on endoscopic management of children and adolescents with chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1884-1892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Anderson MA, Fisher L, Jain R, Evans JA, Appalaneni V, Ben-Menachem T, Cash BD, Decker GA, Early DS, Fanelli RD. Complications of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:467-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wilcox CM, Mönkemüller KF. Wire-assisted minor papilla precut papillotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:83-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |