Published online May 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.5918

Peer-review started: December 5, 2014

First decision: January 22, 2015

Revised: January 30, 2015

Accepted: March 19, 2015

Article in press: March 19, 2015

Published online: May 21, 2015

Processing time: 168 Days and 3.6 Hours

AIM: To compare the success rates and adverse events of early needle-knife fistulotomy (NKF) and double-guidewire technique (DGT) in patients with repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations.

METHODS: From a total of 1650 patients admitted for diagnostic or therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) at a single tertiary care hospital (Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Yangsan, South Korea) between January 2009 and December 2012, 134 (8.1%) patients with unsuccessful biliary cannulation after 5 min trial of conventional methods, together with 5 or more repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations, were enrolled in the study. Early NKF and DGT groups were assigned 67 patients each. In the DGT group, NKF was performed for an additional 7 min if successful cannulation was not achieved.

RESULTS: The success rates with early NKF and the DGT were 79.1% (53/67) and 44.8% (30/67) (P < 0.001), respectively. The incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) was lower in the early NKF group than in the DGT group [4.5% (3/67) vs 14.9% (10/67), P = 0.041]. The mean cannulation times in the early NKF and DGT groups after assignment were 257 s and 312 s (P = 0.013), respectively.

CONCLUSION: Our data suggest that early NKF should be considered as the first approach to selective biliary cannulation in patients with repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations.

Core tip: This retrospective single center analysis of outcomes of early needle-knife fistulotomy (NKF) and double-guidewire technique (DGT) revealed that early NKF has a higher success rate of selective biliary cannulation with a lower incidence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis and shorter procedural time than DGT in patients with repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations.

-

Citation: Kim SJ, Kang DH, Kim HW, Choi CW, Park SB, Song BJ, Hong YM. Needle-knife fistulotomy

vs double-guidewire technique in patients with repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(19): 5918-5925 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i19/5918.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.5918

Successful cannulation of an intended duct is the most important first step for effective biliary and pancreatic procedures during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)[1]. The success rates of conventional methods for biliary cannulation range from 80% to 95%[1-3]. When conventional methods fail to achieve selective cannulation, various alternative techniques can be used. However, prolonged and repetitive manipulation of the papilla during various procedures increases the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP)[4]. Therefore, much effort has been made to develop useful endoscopic techniques in order to perform successful cannulation and reduce PEP. The most commonly used technique in patients with difficult cannulation is precut sphincterotomy, including needle-knife fistulotomy (NKF) and needle-knife papillotomy[5-7]. NKF could be safer than needle-knife papillotomy in terms of PEP because an incision is made a few millimeters apart from the papillary orifice[8,9]. A recent study also reported that early use of NKF in experienced hands is safe and effective[10-12].

The double-guidewire technique (DGT) has also been introduced as a useful method for overcoming difficult biliary cannulation[13-15]. In a previous study comparing DGT with precut sphincterotomy technique, the former required a significantly shorter procedural time but still showed a similar success rate as the latter in biliary cannulation. However, it induced pancreatitis more frequently[16]. A recent study reported that a novel sequential 3-step protocol (traditional cannula with guidewire, DGT, and then NKF) showed an even higher success rate of biliary cannulation (99%)[17]. But 2 prospective randomized studies comparing DGT with using conventional methods in patients with difficult biliary cannulation showed controversial results in terms of selective biliary cannulation and PEP[13,18]. Maeda et al[13] reported that DGT showed a higher cannulation rate with no PEP than the conventional technique (93% and 58%, respectively). However, Herreros de Tejada et al[18] reported that DGT was not superior to the standard cannulation technique (success rates; 47% and 56%, respectively) and was associated with frequent PEP (17% and 8%, respectively)[18]. Therefore, the present study was performed to evaluate whether early NKF or DGT is useful for overcoming difficulty in patients with repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations.

Between January 2009 and December 2012, a total of 1650 patients with pancreaticobiliary disorders and naïve papillae who were admitted for diagnostic or therapeutic ERCP at a single tertiary care hospital (Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Yangsan, Korea) and who gave written informed consent were included in the study. Patients were excluded from the study if one of the following criteria was present: age younger than 15 years, previous surgical biliary-intestinal operations, tumor in the ampulla of Vater, clinical evidence of acute pancreatitis at the time of procedure, coagulopathy, and pregnancy. In patients for whom we had failed to achieve biliary cannulation after attempting for 5 min, accompanied by repetitive pancreatic duct cannulations, early NKF or DGT was performed to achieve biliary cannulation. The data were collected prospectively, but data analysis was done retrospectively.

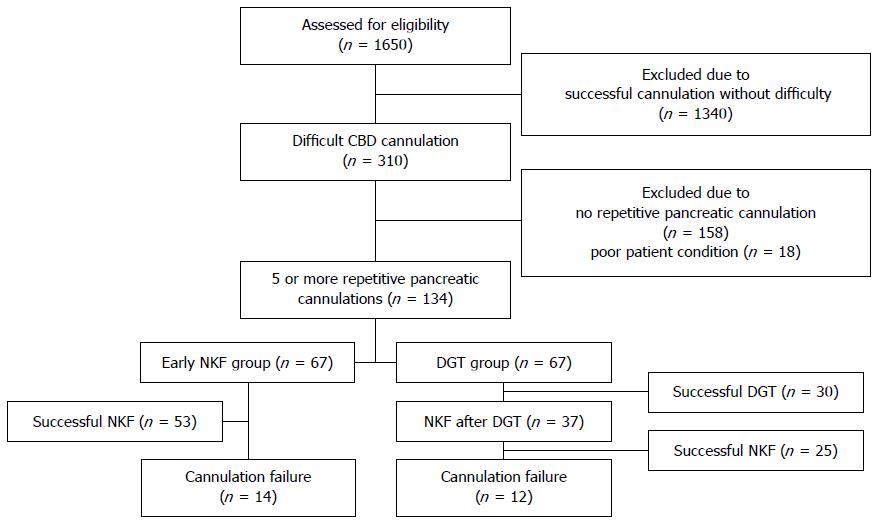

In the DGT group, NKF was performed for an additional 7 min if successful cannulation was not achieved during the trial of DGT. In the early NKF group, endoscopists finished the ERCP without an additional procedure after failure of NKF. Of the 1650 patients with naïve ampullae, 1340 (81.2%) underwent selective cannulation without difficulty, within 5 min. The incidence of PEP was 2.5% in the successful cannulation group without difficulty. Of the 310 patients in whom we did not achieve successful cannulation using the conventional method, 158 patients without repetitive pancreatic cannulation using the conventional method were excluded because of multiple failed attempts to insert the guidewire into the pancreatic duct, which caused excessive edema and papillary trauma and could increase the incidence of PEP. The poor condition/cooperation of 18 patients prevented continued ERCP after conventional method failure. The remaining 134 patients (43.2%) with 5 or more repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations were assigned to the early NKF or DGT group in alternating sequence for selective biliary cannulation (Figure 1).

Two endoscopists who had clinical experience with ERCP for 10 to 20 years participated in the present study; both of them also had experience with NKF and DGT in patients with difficult cannulation. The numbers of patients were distributed equally by two experts.

Our hypothesis was that in patients with repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulation, NKF has a higher success rate to achieve biliary access compared with DGT. Power calculations indicated that a sample size of 140 patients (70 in each group) was needed for an α error of 0.05 and 95% power, based on an expected 80% of cannulation success rate in patients with repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations by early NKF and 50% by DGT. This proportion was based on the results of a previous prospective, randomized trial evaluation NKF or DGT[2,16,18]. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital (IRB No. 05-2014-036) and written informed consent from all patients was obtained prior to study inclusion.

Difficult cannulation was defined as failed selective biliary cannulation within 5 min of using the conventional method, regardless of the number of unintentional pancreatic cannulations. We regarded 5 or more guidewire passings or contrast injections through the pancreatic duct as repetitive pancreatic cannulations. PEP was defined as a new-onset or increased abdominal pain persisting for at least 24 h after the procedure with serum amylase levels 3 times the upper normal limit. The severity of pancreatitis was classified as mild if hospitalization was extended 2 to 3 d after the ERCP, moderate if hospitalization was extended 4 to 10 d, and severe if hospitalization was extended for more than 10 d. Asymptomatic hyperamylasemia after ERCP was defined as 3-fold or greater increase in serum amylase levels at 24 h after the procedure without abdominal pain. Baseline and 24 h post-ERCP serum amylase levels were obtained in all patients. Bleeding was defined as clinically apparent with a decrease in the hemoglobin level higher than 2 g/dL. Failure was defined when biliary cannulation was not achieved within 7 min of trial. The procedural time was defined as the time lapse from assignment to cannulation.

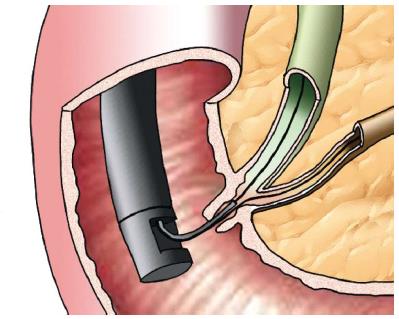

All patients underwent ERCP using a side-view duodenoscope (JF-240 or TJF-240; Olympus Optical Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). A sphincterotome (Ultratome XL, Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass) or an ERCP catheter (Fluoro Tip, Boston Scientific) with a hydrophilic guidewire (0.025- or 0.035-inch Jagwire, Boston Scientific) was used for initial cannulation. Patients with 5 or more repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations were assigned to either NKF or DGT. NKF was done with a needle knife (MicroKnife XL, Boston Scientific). A fistulotomy was performed by making a puncture at the most prominent portion of the papillary roof and then cutting downward toward the papillary orifice. After needle puncture of the bile duct, a sphincterotome with guidewire was used to cannulate the common bile duct. After successful cannulation, endoscopic sphincterotomy was performed. DGT was performed with a device preloaded with a guidewire (Figure 2). Insertion of the guidewire into the main pancreatic duct was guided by fluoroscopy. Placement of a guidewire in the pancreatic duct facilitated cannulation of the bile duct with another sphincterotome or catheter via the same working channel alongside the first guidewire. In cases of failed selective biliary cannulation using DGT, NKF was attempted as a rescue procedure. We placed a pancreatic plastic stent when patients were considered to be at high-risk of PEP (more than 2 of the following risk factors: suspected dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi, young women, injection of contrast into the pancreatic duct, or > 12 min of cannulation attempt). If the patient’s condition permitted delay of procedure for the therapeutic purpose, we performed repeated ERCP in a short interval (at least 2 d after first ERCP). ERCP was performed under conscious sedation using midazolam and pethidine. All patients received pharmacologic prophylaxis of PEP using nafamostat mesilate (Futhan; SK chemicals Life Science Biz, Seoul, Korea).

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). Continuous data are summarized as mean ± SD. The χ2 test or F-test and t test were used for the comparison of categorical variables when appropriate. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Jun Hee Han from Research and Statistical Support, Research Institute of Convergence for Biomedical Science and Technology, Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital.

Of the 310 patients who did not achieve successful cannulation using the conventional method, the success rate using NKF of 158 patients (50.1%) without repetitive pancreatic cannulation was 81.6% (129/158), and the rate of PEP was 7.6% (12/158). For 18 patients (5.8%) with poor condition, an alternative approach could not be permitted after selective cannulation failure and the incidence of PEP was 5.5% (1/18). The remaining 134 patients (43.2%) with 5 or more repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations were assigned to the early NKF or DGT group in alternating sequence for selective biliary cannulation (Figure 1).

The patient characteristics of both the early NKF and DGT groups are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics except for incidence of periampullary diverticula between the early NKF and DGT groups [9 patients (13.4%) vs 25 patients (37.3%), P = 0.001]. The most common indication for ERCP was biliary lithiasis (50.7%, 68/134). Pancreatic stents were successfully placed in all patients who were considered to be at high risk of PEP. There was no difference in the percentage of patients regarding the use of a prophylactic pancreatic duct stent (6.0% in early NKF group and 7.5% in DGT group, P = 1.000).

| Early NKF group | DGT group | P value | |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 65.5 ± 13.1 | 65.2 ± 14.0 | 0.889 |

| Male sex | 33 (49.3) | 34 (50.7) | 0.863 |

| ERCP indications | 0.165 | ||

| Choledocholithiasis | 30 (44.8) | 38 (56.7) | |

| Malignant stricture | 32 (47.8) | 20 (29.9) | |

| Benign biliary stricture | 4 (6.0) | 7 (10.4) | |

| Other | 1 (1.5) | 2 (3.0) | |

| Periampullary diverticulum | 9 (13.4) | 25 (37.3) | 0.001 |

| Intradiverticular ampulla | 0 | 2 | |

| Juxtadiverticular ampulla | 9 | 23 | |

| Pancreas duct stent | 4 (6.0) | 5 (7.5) | 1.000 |

In the early NKF group, successful cannulation was achieved in 53 patients (79.1%). Of the 14 patients with unsuccessful cannulation after the first ERCP, 3, 2, and 9 patients underwent percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), and second ERCP, respectively, within 2 d after the ERCP. Of patients undergoing second ERCPs, 8 patients achieved successful cannulation. The overall success rate of biliary cannulation was 91.0% in the early NKF group including second ERCPs (61/67).

Successful cannulation was achieved in 30 patients (44.8%) of the DGT group. These included 5 patients who obtained wire-guided direct biliary cannulation without DGT (during trials to place a pancreatic guidewire). The cross-over treatment from DGT to NKF was performed in 37 patients who failed biliary cannulation using DGT. Additional success using NFK was achieved in 25 patients (67.5%, 25/37). The overall success rate of biliary cannulation was 82.1% (55/67) in the DGT group. Of the 12 patients with unsuccessful biliary cannulation during first ERCP, 2, 2, and 8 patients underwent PTBD, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), and second ERCP, respectively. Of the patients undergoing second ERCPs, 7 patients had successful biliary cannulation. The overall success rate of biliary cannulation was 92.5% in the DGT group including second ERCPs (62/67) (Table 2).

| Early NKF group | DGT group | P value | |

| Success rate of | 53 (79.1) | 30 (44.8) | < 0.001 |

| assigned technique | |||

| Total success rate of | |||

| 1st ERCP | 53 (79.1) | 55 (82.1) | 0.662 |

| 2nd ERCP | 61 (91.0) | 62 (92.5) | 0.753 |

| Cannulation time after assignment, mean ± SD | 4 min 17 s ± 115 s | 5 min 12 s ± 137 s | 0.013 |

| Pancreatitis, total | 3 (4.5) | 10 (14.9) | 0.041 |

| Mild | 1 | 5 | |

| Moderate | 2 | 5 | |

| Hyperamylasemia | 20 (29.9) | 21 (31.3) | 0.851 |

| Perforation1 | 0 | 1 | 1.000 |

The initial success rate was higher in the early NKF group than in the DGT group (79.1% vs 44.8%, P < 0.001). With an additional NKF as a rescue procedure, the DGT group achieved similar success rate as early NKF alone (82.1% vs 79.1%, P = 0.663). The average procedural time was 4 min 17 s ± 115 s in the early NKF group and 5 min 12 s ± 137 s in the DGT group (P = 0.013).

The early NKF group showed a significantly lower incidence of PEP than the DGT group [3 patients (4.5%) vs 10 patients (14.9%), P = 0.041]. In all patients with prophylactic pancreatic duct stent, PEP was not observed. The severity of pancreatitis was mild (n = 1) and moderate (n = 2) in the early NKF group, and it was mild (n = 5), and moderate (n = 5) in the DGT group. No severe PEP occurred in either group. The incidence of hyperamylasemia showed no significant difference between the early NKF and DGT groups [20 patients (29.9%) vs 21 patients (31.3%), P = 0.851] (Table 2).

No post-NKF bleeding was observed in either group. A single case of perforation occurred during NKF in the DGT group, which was conservatively treated without any eventful outcomes. There was no death related to ERCP in either group.

In patients with diverticula, the initial success rate of biliary cannulation was higher in the early NKF group than in the DGT group [77.8% (7/9) vs 48.0% (12/25), P = 0.240], although the number of each group was too small to conclude statistical significance (P = 0.240). NKF was performed on 13 patients who failed biliary cannulation using DGT. The success of biliary cannulation using NKF after DGT failure was observed in 8 patients (61.5%; 8/13). The DGT subgroup (80.0%) that had additional NKF achieved similar success rate to the early NKF subgroup (77.8%; P = 1.000).

A difference of PEP incidence between the early NKF subgroup (0%; 0 of 9) and DGT subgroup (8.0%; 2 of 25) was observed. Pancreatitis severity was mild (n = 2) in all subgroup patients.

When conventional methods are unsuccessful in achieving deep biliary cannulation, precut sphincterotomy or DGT can be used[1]. NKF is a needle-knife precutting method which has been commonly used to overcome difficult cannulation[5]. It can reduce the risk of PEP by making an incision a few millimeters from the papillary orifice and preventing a direct mechanical injury to the pancreatic duct orifice. Many meta-analyses advocate that early precutting should be performed to reduce the incidence of PEP by decreasing the number of cannulation attempts and unintentional pancreatic cannulations[19-21]. A recent prospective cohort study concluded that if the endoscopist is experienced in ERCP and precut techniques, an early precut strategy should be the preferred cannulation strategy because of its safety and effectiveness[22].

Since its first description by Dumonceau et al[23], DGT has been performed as a promising technique to overcome difficult cannulation and has been widely used in patients with repetitive pancreatic cannulations. Placement of a guidewire deep into the main pancreatic duct facilitates cannulation of the bile duct by providing a variety of benefits, such as opening a stenotic papillary orifice, stabilizing the papilla, lifting the papilla toward the working channel, straightening the pancreatic duct and common channel, or potentially minimizing repetitive injections into the pancreatic duct[1].

In 2009, an algorithm for biliary cannulation suggested that needle-knife sphincterotomy should be performed to overcome difficult cannulation after a minimum of 4 attempts using conventional methods. DGT or pancreatic duct stent insertion should be considered when repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations take place without selective biliary access[24]. However, compared to consistently high success rates of biliary cannulation using NKF (83% to 96%), DGT showed marked variation of successful biliary cannulation rates (47% to 92.6%)[9,11,13,16,18,25]. In addition, a previous study reported that the success rate of biliary cannulation using DGT was just 43.8% (49/112) in patients with repetitive pancreatic duct cannulations[26]. Therefore, there is the need to evaluate the usefulness of early NKF and DGT for selective biliary cannulation in patients with repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations.

Our results showed a low success rate of biliary cannulation using DGT (44.8%) compared to early NKF (79.1%). The success rate of biliary cannulation using DGT in our study is similar to those reported by Herreros de Tejada et al[18] (47%) and Coté et al[27] (54.8%). Considering cases with inadvertent success in those studies, our result is somewhat better. The results from other studies summarized in Table 3 show higher success rates (73.9%-93%) without any description of unintentional biliary cannulations[13,16,28]. Our low success rate of biliary cannulation could be associated with a shorter procedural time and a slightly larger number of patients. Compared to procedural time limits (6-7 min) of studies with low success rates of biliary cannulation using DGT, studies with high success rates had longer procedural times (another 10 min and 10 more attempts without the time limit)[16,27,28]. Although a long procedural time increased the success rate of biliary cannulation using DGT to 73.9% or 79.4%, the incidence of PEP was markedly increased to 21.7% or 38.2% compared to 2.4% or 17% in studies with low success rates[16,18,27,28]. A low success rate of biliary cannulation was also observed in a multicenter study with a relatively large number of patients[18]. In contrast, previous studies that were performed on a small number of patients in a single center and by a single endoscopist showed high success rates of biliary cannulation[16,28]. In addition, a study with the highest success rate of biliary cannulation, shown in Table 3, reported the difficult cannulation rate was as high as 49.5%[13]. Therefore, a selection bias caused by a small sample size and a single endoscopist can lead to a good success rate of biliary cannulation using DGT.

| Study | Study design | Patients screened | Patients randomized DGT | Timing of DGT | Success rate | Inadvertent success in DGT | PEP | Failure |

| Maeda et al[13], 2003 | Single-center randomized study | 107 | 27 (25) | Unsuccessful within 10 min | 93% | NA | 0% | NA |

| Herreros de Tejada et al[18], 2009 | Multicenter randomized study | 845 | 97 (11) | After 5 attempts | 47% | 18% | 17% | 10 more attempts |

| Angsuwatcharakon et al[16], 2012 | Single-center randomized study | 426 | 23 (5) | Unsuccessful within 10 min | 73.9% | NA | 21.7% | Another 10 min |

| Coté et al[27], 2012 | Two-center randomized study | 442 | 42 (10) | Unsuccessful within 6 min or 3 PD cannulations | 54.8% | 16.7% | 2.4% | Another 6 min |

| Yoo et al[28], 2013 | Single-center randomized study | 1394 | 34 (2) | Unsuccessful within 10 min | 79.4% | NA | 38.2% | 10 more attempts |

The success rate of biliary cannulation using a stepwise approach (DGT and NKF sequentially) in the DGT group was similar to that in the early NKF group alone (82.1% vs 79.2%, P = 0.665). This means that DGT itself does not provide additional advantages in achieving selective biliary cannulation. Instead, a long procedural time is required because half of the patients not only failed cannulation using DGT, but also underwent additional NKFs to rescue DGT failure. In addition, the DGT group (14.9%) showed a significantly higher incidence of PEP than the early NKF group (4.2%). Repetitive contact with the papilla during DGT and a longer procedural time may be the reason for the high incidence of PEP. Pancreatic stent placement could be useful for reducing the incidence of PEP[29,30]. However, failure of pancreatic stent placement can cause severe forms of pancreatitis[31]. Therefore, it is appropriate to place a pancreas stent selectively in a high-risk group. Considering these results, DGT is frequently complicated by pancreatitis and requires more time to achieve a similar success rate to NKF.

There was a significant difference in the baseline characteristics of periampullary diverticula between the 2 groups. The success rate of biliary cannulation using NKF was not significantly different between patients with periampullary diverticula and those without [77.8% (7/9) vs 79.5% (46/58)]. As for DGT, there was also no significant difference in the success rate of biliary cannulation whether periampullary diverticula were present or not [48% (12/25) vs 42% (18/42)]. The presence of periampullary diverticula did not influence the success rate of biliary cannulation. Despite the small number of patients in the early NKF group, our results are consistent with a previous study which reported that NKF can be performed effectively and safely in patients with periampullary diverticula and difficult biliary cannulation[32].

Considering a low success rate of biliary cannulation, a long procedural time, and a high incidence of PEP in the DGT group, NKF should be performed as early as possible in patients with repetitive unintentional pancreatic duct cannulations. Subsequent options to pursue when NKF fails include repeated ERCP attempts or consideration of alternative approaches, such as percutaneous or EUS duct-access procedures. DGT could be considered in special conditions, such as a very small and flat papilla in which NKF has high risk for perforation, or the location of the papilla in the lower rim or just inside the diverticulum where DGT can evert the papilla to the duodenal lumen. DGT can help less experienced endoscopists to avoid the risks of precut sphincterotomy, such as bleeding and perforation.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the study was not a randomized prospective controlled study and this could cause uneven distribution of patients with periampullary diverticula among the two groups. Endoscopists knew the assigned method before the allocation; this might have influenced the decision to include patients in this study. Secondly, it has a single-center design with small sample size, although its sample size is relatively large compared to that of previous studies. This might influence the interpretation of the differences in adverse events including PEP. Finally, this study was done by very experienced endoscopists, limiting the generalizability of this study finding. Therefore, large-scale prospective multicenter studies are needed to overcome these limitations. However, we think that a strengthening factor in the current study includes minimizing PEP risk caused by unsuccessful conventional cannulations by using the limit of 5 min before allocation into an assigned method, and it is the first study to compare early NKF and DGT in patients with repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations.

In conclusion, in patients with repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations, NKF had a higher success rate of selective biliary cannulation with a lower incidence of PEP than DGT. Therefore, these data suggest that early NKF should be considered as the first approach to selective biliary cannulation in such patients.

Precut sphincterotomy using needle-knife fistulotomy (NKF) or needle-knife papillotomy has been used in patients with failed conventional biliary cannulation. Double-guidewire technique (DGT) has also been reported to be useful for difficult biliary cannulation.

Most previous studies evaluated the outcomes of DGT compared to precut sphinterotomy or standard cannulation technique to overcome difficult biliary cannulation. There has been no study to compare the usefulness of early NKF and DGT in patients with repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations.

An algorithm for biliary cannulation suggested by Bourke et al described that DGT or pancreatic duct stent insertion should be considered when repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations take place without selective biliary access. The authors measured the usefulness of early NKF and DGT for selective biliary cannulation in patients with repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations.

Early NKF should be considered as the first approach to selective biliary cannulation in patients with repetitive unintentional pancreatic cannulations. DGT can help less experienced endoscopists to avoid the risks of precut sphincterotomy, such as bleeding and perforation.

Although there is no universally agreed cut-off for difficult cannulation, the authors defined an unsuccessful biliary cannulation within 5 min of using the conventional method as failure, regardless of the number of unintentional pancreatic cannulations. The authors regarded 5 or more guidewire passings or contrast injections through the pancreatic duct as repetitive pancreatic cannulations.

This article is about selective biliary cannulation techniques for the difficult biliary cannulation cases. The authors especially compared early NKF with DGT, and concluded that early NFK achieved a higher success rate of cannulation with a lower incidence of PEP. We often experience difficult cannulation cases, and we try DGT or some precut techniques. This paper is very important clinically and interesting for many endoscopists who perform ERCP.

P- Reviewer: Kawaguchi Y S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Logan S E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Freeman ML, Guda NM. ERCP cannulation: a review of reported techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:112-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tang SJ, Haber GB, Kortan P, Zanati S, Cirocco M, Ennis M, Elfant A, Scheider D, Ter H, Dorais J. Precut papillotomy versus persistence in difficult biliary cannulation: a prospective randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2005;37:58-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Binmoeller KF, Seifert H, Gerke H, Seitz U, Portis M, Soehendra N. Papillary roof incision using the Erlangen-type pre-cut papillotome to achieve selective bile duct cannulation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:689-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty MB, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, Overby CS, Aas J, Ryan ME, Bochna GS. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 801] [Cited by in RCA: 835] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Udd M, Kylänpää L, Halttunen J. Management of difficult bile duct cannulation in ERCP. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2:97-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Saritas U, Ustundag Y, Harmandar F. Precut sphincterotomy: a reliable salvage for difficult biliary cannulation. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Jamry A. Comparative analysis of endoscopic precut conventional and needle knife sphincterotomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2227-2233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mavrogiannis C, Liatsos C, Romanos A, Petoumenos C, Nakos A, Karvountzis G. Needle-knife fistulotomy versus needle-knife precut papillotomy for the treatment of common bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:334-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Katsinelos P, Gkagkalis S, Chatzimavroudis G, Beltsis A, Terzoudis S, Zavos C, Gatopoulou A, Lazaraki G, Vasiliadis T, Kountouras J. Comparison of three types of precut technique to achieve common bile duct cannulation: a retrospective analysis of 274 cases. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:3286-3292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cennamo V, Fuccio L, Repici A, Fabbri C, Grilli D, Conio M, D’Imperio N, Bazzoli F. Timing of precut procedure does not influence success rate and complications of ERCP procedure: a prospective randomized comparative study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:473-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Lim JU, Joo KR, Cha JM, Shin HP, Lee JI, Park JJ, Jeon JW, Kim BS, Joo S. Early use of needle-knife fistulotomy is safe in situations where difficult biliary cannulation is expected. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1384-1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Choudhary A, Winn J, Siddique S, Arif M, Arif Z, Hammoud GM, Puli SR, Ibdah JA, Bechtold ML. Effect of precut sphincterotomy on post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4093-4101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Maeda S, Hayashi H, Hosokawa O, Dohden K, Hattori M, Morita M, Kidani E, Ibe N, Tatsumi S. Prospective randomized pilot trial of selective biliary cannulation using pancreatic guide-wire placement. Endoscopy. 2003;35:721-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Szaflarski M, Kudel I, Cotton S, Leonard AC, Tsevat J, Ritchey PN. Multidimensional assessment of spirituality/religion in patients with HIV: conceptual framework and empirical refinement. J Relig Health. 2012;51:1239-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ito K, Horaguchi J, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Koshita S, Kanno Y, Ogawa T, Masu K, Hashimoto S. Clinical usefulness of double-guidewire technique for difficult biliary cannulation in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:442-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Angsuwatcharakon P, Rerknimitr R, Ridtitid W, Ponauthai Y, Kullavanijaya P. Success rate and cannulation time between precut sphincterotomy and double-guidewire technique in truly difficult biliary cannulation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:356-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vihervaara H, Grönroos JM. Feasibility of the novel 3-step protocol for biliary cannulation--a prospective analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:161-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Herreros de Tejada A, Calleja JL, Díaz G, Pertejo V, Espinel J, Cacho G, Jiménez J, Millán I, García F, Abreu L. Double-guidewire technique for difficult bile duct cannulation: a multicenter randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:700-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cennamo V, Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Eusebi LH, Ceroni L, Laterza L, Fabbri C, Bazzoli F. Can early precut implementation reduce endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related complication risk? Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Endoscopy. 2010;42:381-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Zhu JH, Liu Q, Zhang DQ, Feng H, Chen WC. Evaluation of early precut with needle-knife in difficult biliary cannulation during ERCP. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:3606-3610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Swan MP, Alexander S, Moss A, Williams SJ, Ruppin D, Hope R, Bourke MJ. Needle knife sphincterotomy does not increase the risk of pancreatitis in patients with difficult biliary cannulation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:430-436.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lopes L, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Rolanda C. Early precut fistulotomy for biliary access: time to change the paradigm of “the later, the better”? Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:634-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dumonceau JM, Devière J, Cremer M. A new method of achieving deep cannulation of the common bile duct during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 1998;30:S80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bourke MJ, Costamagna G, Freeman ML. Biliary cannulation during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: core technique and recent innovations. Endoscopy. 2009;41:612-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Recchia S, Coppola F, Ferrari A, Righi D, Zanon E, Verme G. Fistulosphincterotomy in the endoscopic approach to biliary tract diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1607-1609. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Xinopoulos D, Bassioukas SP, Kypreos D, Korkolis D, Scorilas A, Mavridis K, Dimitroulopoulos D, Paraskevas E. Pancreatic duct guidewire placement for biliary cannulation in a single-session therapeutic ERCP. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1989-1995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Coté GA, Mullady DK, Jonnalagadda SS, Keswani RN, Wani SB, Hovis CE, Ammar T, Al-Lehibi A, Edmundowicz SA, Komanduri S. Use of a pancreatic duct stent or guidewire facilitates bile duct access with low rates of precut sphincterotomy: a randomized clinical trial. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:3271-3278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yoo YW, Cha SW, Lee WC, Kim SH, Kim A, Cho YD. Double guidewire technique vs transpancreatic precut sphincterotomy in difficult biliary cannulation. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:108-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lee TH, Moon JH, Choi HJ, Han SH, Cheon YK, Cho YD, Park SH, Kim SJ. Prophylactic temporary 3F pancreatic duct stent to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients with a difficult biliary cannulation: a multicenter, prospective, randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:578-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Choudhary A, Bechtold ML, Arif M, Szary NM, Puli SR, Othman MO, Pais WP, Antillon MR, Roy PK. Pancreatic stents for prophylaxis against post-ERCP pancreatitis: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:275-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Freeman ML, Overby C, Qi D. Pancreatic stent insertion: consequences of failure and results of a modified technique to maximize success. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:8-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Park CS, Park CH, Koh HR, Jun CH, Ki HS, Park SY, Kim HS, Choi SK, Rew JS. Needle-knife fistulotomy in patients with periampullary diverticula and difficult bile duct cannulation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1480-1483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |