Published online May 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i18.5647

Peer-review started: July 9, 2014

First decision: August 6, 2014

Revised: August 29, 2014

Accepted: November 18, 2014

Article in press: November 19, 2014

Published online: May 14, 2015

Processing time: 313 Days and 10.7 Hours

AIM: To investigate if correction of hypovitaminosis D before initiation of Peg-interferon-alpha/ribavirin (PegIFN/RBV) therapy could improve the efficacy of PegIFN/RBV in previously null-responder patients with chronic genotype 1 or 4 hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

METHODS: Genotype 1 or 4 HCV-infected patients with null response to previous PegIFN/RBV treatment and with hypovitaminosis D (< 30 ng/mL) prospectively received cholecalciferol 100000 IU per week for 4 wk [from week -4 (W-4) to W0], followed by 100000 IU per month in combination with PegIFN/RBV for 12 mo (from W0 to W48). The primary outcome was the rate of early virological response defined by an HCV RNA < 12 IU/mL after 12 wk PegIFN/RBV treatment.

RESULTS: A total of 32 patients were included, 19 (59%) and 13 (41%) patients were HCV genotype 1 and 4, respectively. The median baseline vitamin D level was 15 ng/mL (range: 7-28). In modified intention-to-treat analysis, 29 patients who received at least one dose of PegIFN/RBV were included in the analysis. All patients except one normalized their vitamin D serum levels. The rate of early virologic response was 0/29 (0%). The rate of HCV RNA < 12 IU/mL after 24 wk of PegIFN/RBV was 1/27 (4%). The safety profile was favorable.

CONCLUSION: Addition of vitamin D to PegIFN/RBV does not improve the rate of early virologic response in previously null-responders with chronic genotype 1 or 4 HCV infection.

Core tip: Vitamin D deficiency is commonly found in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and was shown to correlate with sustained virologic response rates to peg-interferon-alpha/ribavirin (PegIFN/RBV) therapy. The addition of vitamin D to PegIFN/RBV was well tolerated but did not improve the rate of early virologic response in previously null-responder patients with chronic genotype 1 or 4 HCV infection.

- Citation: Terrier B, Lapidus N, Pol S, Serfaty L, Ratziu V, Asselah T, Thibault V, Souberbielle JC, Carrat F, Cacoub P. Vitamin D in addition to peg-interferon-alpha/ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C virus infection: ANRS-HC25-VITAVIC study. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(18): 5647-5653

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i18/5647.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i18.5647

In patients with genotype 1 or 4 hepatitis C virus (HCV) chronic infection who failed to obtain a sustained virological response (SVR) to peg-interferon-alpha/ribavirin (PegIFN/RBV) treatment, the chance of a cure is low. Previous studies showed rates of early virological response (EVR) and SVR of roughly 7% in non-responders after retreatment with PegIFN/RBV[1,2]. Protease inhibitors specific to the HCV nonstructural 3/4A serine protease, i.e., telaprevir and boceprevir, emerged as promising therapies in combination with PegIFN/RBV in chronic genotype 1 HCV infection, by significantly improving SVR rates[3-6]. Despite promising results in naïve patients, treatment of non-responders to PegIFN/RBV therapy with these triple therapies resulted in less than 30% response rates[7]. Other promising HCV drug combinations, with or without PegIFN, very recently showed high SVR rates in previously treated patients with genotype 1 HCV infection[8]. However, adverse effects and/or the cost of such very effective therapeutic combinations signals the need for other well tolerated and cheaper therapeutic approaches.

Vitamin D deficiency is frequent in patients with chronic HCV infection. Hypovitaminosis D (≤ 30 ng/mL) was reported in three-quarters of genotype 1 patients[9] and in roughly 90% of French patients[10]. Besides its musculoskeletal effects, vitamin D seems to play a critical role in the modulation of the balance between effector and regulatory immune cells. Previous studies in genotype 1 chronic HCV infection demonstrated correlations between hypovitaminosis D and severe liver fibrosis and low virological response rates to PegIFN/RBV therapy[9]. 25-OH vitamin D in addition to PegIFN/RBV in previously untreated genotype 1 patients was also shown to significantly improve EVR(94% vs 48%) and SVR (86% vs 42%)[11].

We hypothesized that correction of hypovitaminosis D before initiation of PegIFN/RBV therapy and maintenance of an optimal vitamin D serum concentration during antiviral therapy could improve the efficacy of PegIFN/RBV therapy in null-responder patients with genotype 1 or 4 chronic HCV hepatitis.

This multicenter, prospective, open-label and uncontrolled study was designed to assess the efficacy of a combination of vitamin D and PegIFN/RBV for retreatment of null-responder patients with genotype 1 or 4 chronic HCV infection (VITAVIC study, NCT NCT01226446).

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards and committees for the protection of persons at the individual study sites. The study was conducted according to the current regulations of the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines, and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent before participating in any protocol-specific procedures. Patients were enrolled from 25 November, 2010 to 13 September, 2011.

To be eligible for the study, patients had to be older than 18 years, be chronically infected with genotype 1 or 4 HCV, be null-responders to previous PegIFN/RBV therapy, have received ≥ 80% of PegIFN/RBV therapy during previous therapy, and to have hypovitaminosis D (< 30 ng/mL). Null-responders were defined by a less than 2 log10 IU/mL decrease in HCV viral load at week 12 (W12) during the previous PegIFN/RBV course.

Patients were assigned to prospectively receive cholecalciferol 100000 IU once per wk for 4 wk [from week -4 (W-4) to W0], followed by 100000 IU once per month in combination with PegIFN/RBV for 12 months (from W0 to W48). PegIFN/RBV combination treatment was similar to the previous PegIFN/RBV course, i.e., type (alpha 2a or alpha 2b) and dose of PegIFN, and dose of RBV).

The primary outcome assessment was the rate of EVR defined by an HCV RNA < 12 IU/mL after 12 wk of PegIFN/RBV.

Secondary outcome measures included: (1) changes in HCV viral load after correction of vitamin D deficiency at day 0; (2) changes in HCV viral load at W4 and W12; and (3) the rate of HCV RNA < 12 IU/mL at W24 and W72 (SVR).

Physical examination, and hematological and biochemical assessments were performed at each planned visit. All reported adverse events were graded (1: mild to 4: life-threatening) using the ANRS grading system[12] and coded using MedDRA v16.1 by a trained monitor.

HCV-RNA was detected with a PCR assay (Abbott Molecular, Rungis, France) with a detection limit of 12 IU/mL. An EVR was defined as HCV-RNA < 12 IU/mL at week 12. SVR was defined as HCV-RNA < 12 IU/mL at week 72. Patients were assessed for hepatic inflammation and fibrosis using liver biopsy and/or using serum biochemical markers. Inflammatory lesions and fibrosis on liver biopsy were graded as previously reported[13]. Inflammation and fibrosis were also assessed using ActiTest® and FibroTest®[14]. HCV-RNA tests, genotyping, and histological assessment of liver biopsy were performed in each center’s laboratory.

Blood samples were immediately centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min and serum samples were stored at -80 °C. Serum 25(OH)D was measured using a radioimmunossay (DiaSorin, Stillwater, MN, United States), as previously described[15].

Intention-to-treat analyses of both primary and secondary outcomes were carried out, in all patients who received at least one dose of both PegIFN/RBV and cholecalciferol. Missing values for all outcomes were imputed as failures (i.e., absence of HCV RNA < 12 IU/mL and absence of changes in HCV viral load > 2 log10 after correction of vitamin D deficiency, respectively). Outcomes presented as rates (EVR and SVR) were calculated with their 95% confidence interval (CI) using the binomial exact test. Changes in HCV viral load were calculated with their 95%CI using linear mixed-effects models accounting for repeated measures.

Associations between EVR or SVR and baseline covariates or time-dependent vitamin D were explored with univariable logistic models. Associations between HCV viral load change and baseline covariates or time-dependent vitamin D were explored with the analysis of comparisons between visits (two-way analysis of variance on linear mixed-effects models accounting for repeated measures). P-values were adjusted for the multiple comparisons.

Vitamin D levels were compared with the use of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. All analyses were performed using R software version 3.0 (Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

The protocol was planned to include 40 patients in order to demonstrate a difference of 14% in the primary criteria, based on a hypothesized EVR rate of 21% with vitamin D in comparison to a hypothesized EVR rate of 7% in the absence of vitamin D, with an alpha risk of 5% and a power of 80%. Seven responses or more were expected to establish the efficacy of the vitamin D strategy.

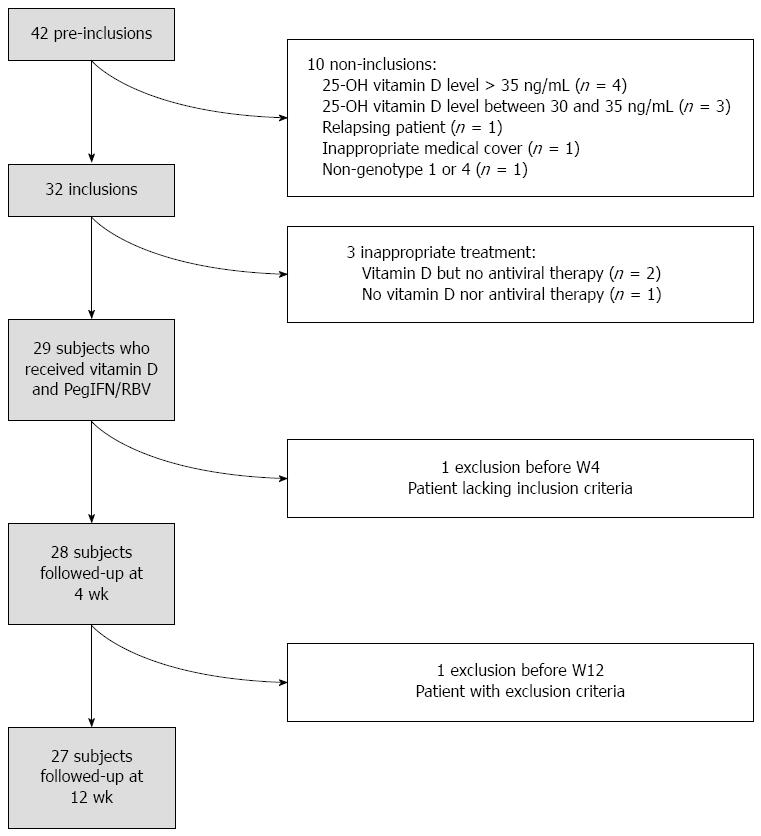

Of the 40 planned patients, 32 [22 male, 10 female; median age 53 years (range: 25-79)] were included before the trial was stopped because of a lack of efficacy. The statistical analysis was based on 29 patients who received vitamin D and Peg-IFN/RBV (PegIFN alpha2a in 15 patients and PegIFN alpha2b in 14 patients). The flow chart of the trial protocol is indicated in Figure 1. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Value |

| Age (yr) | 53.6 (50.6, 60.9) |

| Male | 20 (68.9) |

| HCV infection duration (yr) | 13.5 (5.6, 17.2) |

| Geographic origin | |

| North Africa | 6 (20.7) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 5 (17.2) |

| West Indies | 1 (3.4) |

| Asia | 1 (3.4) |

| Eastern Europe | 1 (3.4) |

| Northern Europe | 15 (51.7) |

| HCV genotype | |

| 1 | 8 (27.6) |

| 1a | 4 (13.8) |

| 1b | 6 (20.7) |

| 4 | 4 (13.8) |

| 4a | 5 (17.2) |

| 4c | 2 (6.9) |

| Liver biopsy (n = 20) | |

| Activity Metavir score | |

| 0 | 3 (15) |

| 1 | 9 (45) |

| 2 | 7 (35) |

| 3 | 1 (5) |

| Fibrosis Metavir score | |

| 1 | 6 (30) |

| 2 | 7 (35) |

| 3 | 4 (20) |

| 4 | 3 (15) |

| Steatosis | 12 (60) |

| Serum biomarkers (n = 18) | |

| Actitest | 0.51 (0.41, 0.66) |

| Fibrotest | 0.64 (0.47, 0.76) |

| Activity Metavir score | |

| 0 | 1 (5.6) |

| 1 | 3 (16.7) |

| 2 | 8 (44.4) |

| 3 | 6 (33.3) |

| Fibrosis Metavir score | |

| 0 | 3 (16.7) |

| 1 | 2 (11.1) |

| 2 | 4 (22.2) |

| 3 | 3 (16.7) |

| 4 | 6 (33.3) |

| Fibroscan (kPa) (n = 20) | 7.3 (6.2, 12.4) |

| > 10 kPa | 8 (40) |

| Hypertension | 7 (24.1) |

| Dyslipidemia | 2 (6.9) |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| No | 25 (86.2) |

| Rarely | 2 (6.9) |

| Regular | 2 (6.9) |

| Vitamin D serum level (visit 1, ng/mL) | 15 (11, 23) |

| HCV viremia at inclusion (Log) | 6.02 (5.80, 6.29) |

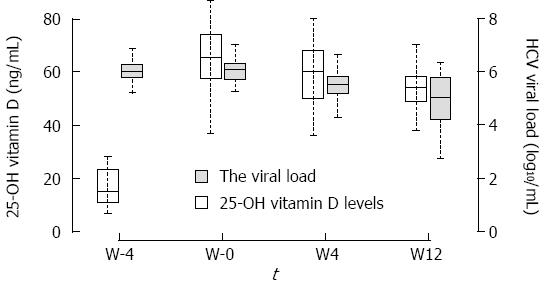

At inclusion (W-4), the median 25-OH vitamin D level was 15 ng/mL [interquartile range (IQR): 11-23], and median HCV viral load was 6.02 log10IU/mL (IQR: 5.80-6.29). During the study, 25-OH vitamin D increased significantly to 66 (58-74) at W0, 60 (50-68) at W4, and 54 (49-58) ng/mL at W12 (P < 0.0001) (Figure 2).

Of the 29 patients analyzed, none achieved the primary endpoint at 12 wk after initiation of Peg-IFN/RBV therapy (proportion 0%, 95%CI: 0%-11.9%).

Median HCV viral load remained stable between W-4 and W0, with viral load of 6.08 (IQR: 5.72-6.30) at W0 (P = 0.99 compared to W-4). At W4 of PegIFN/RBV compared to W-4, median HCV viral load significantly decreased to 5.54 IU/mL (IQR: 5.19-5.83) (P < 0.001). Only one patient had a reduction in HCV viral load greater than 2 log10IU/mL (proportion 3.4%, 95%CI: 0%-17.8%) at W4. No association between the change in HCV viral load at W0 or W4 and baseline vitamin D levels or patients’ characteristics was found.

At W12 of PegIFN/RBV compared to W4, median HCV viral load significantly decreased to 5.04 IU/mL (IQR: 4.22-5.76) (P < 0.001). Six of 29 (21%) patients had a reduction in HCV viral load greater than 2 log10IU/mL between W-4 and W12 (proportion 20.7%, 95%CI: 8%-39.7%). No association between baseline characteristics and change in HCV viral load at W12 was found.

Six patients with a greater than 2log10IU/mL decrease in viral load at W12 were treated up to W24. Two achieved a virologic response and three others had a reduction in HCV viral load greater than 2 log10IU/mL. Since only six patients and one patient were still followed up at W24 and W72, respectively, analyses regarding the related outcomes were not performed.

Twenty six events in 11 patients (38%) were recorded as grade 3, and 2 events in 2 patients (7%) were recorded as grade 4. No grade 3/4 adverse event was attributable to vitamin D supplementation.

Previous data in naïve genotype 1 HCV-infected patients have demonstrated correlations between hypovitaminosis D and low SVR rates to PegIFN/RBV therapy[9]. A significant improvement in EVR and SVR after vitamin D supplementation during PegIFN/RBV therapy has been reported[11]. Therefore, we hypothesized that correction of hypovitaminosis D before initiation of PegIFN/RBV therapy and maintenance of an optimal vitamin D serum concentration during antiviral therapy could improve the efficacy of PegIFN/RBV in null-responder patients with genotype 1 or 4 chronic HCV hepatitis. In addition, previous data demonstrated the major role of vitamin D and the vitamin D receptor (VDR) in the regulation of T cell activation by control of T cell antigen receptor signaling[16], supporting the potential beneficial effect of vitamin D supplementation in chronic infections.

We decided to include genotype 1 or 4 HCV infected patients with a previous PegIFN/RBV therapy null response and hypovitaminosis D as they were anticipated to have very low SVR rates in case of re-treatment with PegIFN/RBV. In the present study, we demonstrated that the addition of vitamin D to PegIFN/RBV did not improve the rate of EVR in previously null-responder patients with chronic genotype 1 or 4 HCV infection. Our findings are disappointing considering the results of previous studies, and are in clear contrast with results from several observational and interventional studies. However, in contrast to the study by Abou-Mouch et al[11], reporting a positive effect of vitamin D supplementation in naïve genotype 1 HCV infected patients, our study assessed the benefit of vitamin D supplementation in null-responders who represent a challenging population of patients with poor response to antiviral therapies. Along this line, we cannot exclude that our inclusion criteria, i.e., null-responders, resulted in selection of patients in whom the impact of adding vitamin D was negligible.

HCV viral load remained stable during the initial vitamin D supplementation and significantly decreased under PegIFN/RBV therapy combined with vitamin D supplementation, but without reaching our primary criteria. The change in the serum 25-OH vitamin D level showed that vitamin D supplementation was effective and safe to obtain a significant and persistent increase in serum 25-OH vitamin D. This finding indicates that our disappointing results could not be related to serum 25-OH vitamin D insufficiency in our patients.

We must acknowledge the limitations of our study. Because we aimed to analyze the efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in the era of new antiviral agents in a more challenging population of patients, i.e., null-responder patients, we conducted an open-label, uncontrolled study of superiority design that planned to include 40 patients. Only 32 patients were included before the trial was stopped for lack of efficacy, and 29 patients were analyzable for the primary endpoint. Although it could have been a limitation to draw any conclusion about the response to vitamin D supplementation, our findings probably demonstrate a lack of interest in vitamin D status in previously null-responder patients with chronic genotype 1 or 4 HCV infection. In addition, chose weekly then monthly administration of vitamin D rather than daily dosing. Supplementation with vitamin D was previously shown to be achieved equally well with daily, weekly, or monthly dosing frequencies[17]. Therefore, our protocol was chosen to optimize adherence to long-term vitamin D supplementation.

In conclusion, the addition of vitamin D to PegIFN/RBV does not improve the EVR rate in previously null-responder patients with chronic genotype 1 or 4 HCV infection. The lack of an EVR suggests that it is very unlikely that there is a beneficial effect of vitamin D supplementation on SVR in this type of difficult to treat patient. However, based on previous studies, vitamin D supplementation may still represent an alternative therapeutic option in naïve patients in which new specifically targeted antiviral therapy for hepatitis C would not be available or contraindicated.

We thank Noëlle Pouget and Hubert Paniez for their assistance in collecting data.

In patients with genotype 1 or 4 hepatitis C virus (HCV) chronic infection who do not have a sustained virological response (SVR) to peg-interferon-alpha/ribavirin (PegIFN/RBV) treatment, chances of cure are low. Retreatment of previous non-responders to PegIFN/RBV therapy with triple therapies results in less than 30% SVR, indicating that other HCV drug combinations, with or without PegIFN, are needed. New HCV treatments will modify the care of chronic HCV infection in the near future in high-income countries. However, the place of such new very expensive HCV treatment combinations remains to be defined in low-income countries where cheaper alternatives have to be found.

Vitamin D deficiency is common in patients with chronic HCV infection, and previous data have demonstrated correlations between hypovitaminosis D and low SVR rates to PegIFN/RBV therapy. Also, authors have reported that vitamin D in addition to PegIFN/RBV therapy for naïve genotype 1 HCV patients with chronic hepatitis improved EVR and SVR.

The current study investigated whether the correction of hypovitaminosis D before initiation of PegIFN/RBV therapy could improve the efficacy of PegIFN/RBV in previously null-responder patients with chronic genotype 1 or 4 HCV infection. We found that the addition of vitamin D to PegIFN/RBV was well tolerated but did not improve the rate of early virologic response in previously null-responder patients with chronic genotype 1 or 4 HCV infection.

This study demonstrated a lack of efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in previously null-responder patients with chronic genotype 1 or 4 HCV infection. However, vitamin D supplementation could still represent an alternative therapeutic option in naïve patients in whom new specifically targeted antiviral therapy for hepatitis C would not be available or be contraindicated.

Hepatitis C virus infection is a chronic liver disease that can be complicated by cirrhosis, liver failure and liver cancer. Rates of early and sustained virologic responses in non-responders after retreatment with PegIFN/RBV is low. Besides its musculoskeletal effects, vitamin D seems to play a critical role in the modulation of the balance between effector and regulatory immune cells. Vitamin D supplementation may thus be beneficial in some chronic C virus hepatitis patients.

This study attempted to answer an important clinical question.

P- Reviewer: Wong GLH S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Cant MR E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | McHutchison JG, Manns MP, Muir AJ, Terrault NA, Jacobson IM, Afdhal NH, Heathcote EJ, Zeuzem S, Reesink HW, Garg J. Telaprevir for previously treated chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1292-1303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 570] [Cited by in RCA: 535] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jensen DM, Marcellin P, Freilich B, Andreone P, Di Bisceglie A, Brandão-Mello CE, Reddy KR, Craxi A, Martin AO, Teuber G. Re-treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis C who do not respond to peginterferon-alpha2b: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:528-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McHutchison JG, Everson GT, Gordon SC, Jacobson IM, Sulkowski M, Kauffman R, McNair L, Alam J, Muir AJ. Telaprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1827-1838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 851] [Cited by in RCA: 809] [Article Influence: 50.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hézode C, Forestier N, Dusheiko G, Ferenci P, Pol S, Goeser T, Bronowicki JP, Bourlière M, Gharakhanian S, Bengtsson L. Telaprevir and peginterferon with or without ribavirin for chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1839-1850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 849] [Cited by in RCA: 794] [Article Influence: 49.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Poordad F, McCone J, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, Sulkowski MS, Jacobson IM, Reddy KR, Goodman ZD, Boparai N. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1195-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1996] [Cited by in RCA: 1981] [Article Influence: 141.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, Marcellin P, Vierling JM, Zeuzem S, Poordad F, Goodman ZD, Sings HL, Boparai N. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1207-1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1306] [Cited by in RCA: 1308] [Article Influence: 93.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Asselah T. Triple therapy with boceprevir or telaprevir for prior HCV non-responders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:455-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lawitz E, Poordad FF, Pang PS, Hyland RH, Ding X, Mo H, Symonds WT, McHutchison JG, Membreno FE. Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir fixed-dose combination with and without ribavirin in treatment-naive and previously treated patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection (LONESTAR): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:515-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 429] [Cited by in RCA: 443] [Article Influence: 40.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Petta S, Cammà C, Scazzone C, Tripodo C, Di Marco V, Bono A, Cabibi D, Licata G, Porcasi R, Marchesini G. Low vitamin D serum level is related to severe fibrosis and low responsiveness to interferon-based therapy in genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2010;51:1158-1167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 325] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Terrier B, Jehan F, Munteanu M, Geri G, Saadoun D, Sène D, Poynard T, Souberbielle JC, Cacoub P. Low 25-hydroxyvitamin D serum levels correlate with the presence of extra-hepatic manifestations in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51:2083-2090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Abu-Mouch S, Fireman Z, Jarchovsky J, Zeina AR, Assy N. Vitamin D supplementation improves sustained virologic response in chronic hepatitis C (genotype 1)-naïve patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:5184-5190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hézode C, Fontaine H, Dorival C, Larrey D, Zoulim F, Canva V, de Ledinghen V, Poynard T, Samuel D, Bourlière M. Triple therapy in treatment-experienced patients with HCV-cirrhosis in a multicentre cohort of the French Early Access Programme (ANRS CO20-CUPIC) - NCT01514890. J Hepatol. 2013;59:434-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 30.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bedossa P, Poynard T. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. The METAVIR Cooperative Study Group. Hepatology. 1996;24:289-293. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Imbert-Bismut F, Ratziu V, Pieroni L, Charlotte F, Benhamou Y, Poynard T. Biochemical markers of liver fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C virus infection: a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;357:1069-1075. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Hollis BW, Kamerud JQ, Selvaag SR, Lorenz JD, Napoli JL. Determination of vitamin D status by radioimmunoassay with an 125I-labeled tracer. Clin Chem. 1993;39:529-533. [PubMed] |

| 16. | von Essen MR, Kongsbak M, Schjerling P, Olgaard K, Odum N, Geisler C. Vitamin D controls T cell antigen receptor signaling and activation of human T cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:344-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 387] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ish-Shalom S, Segal E, Salganik T, Raz B, Bromberg IL, Vieth R. Comparison of daily, weekly, and monthly vitamin D3 in ethanol dosing protocols for two months in elderly hip fracture patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3430-3435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |