Published online May 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i18.5555

Peer-review started: October 28, 2014

First decision: November 14, 2014

Revised: December 3, 2014

Accepted: January 16, 2015

Article in press: January 16, 2015

Published online: May 14, 2015

Processing time: 208 Days and 1 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the effectiveness of barium impaction therapy for patients with colonic diverticular bleeding.

METHODS: We reviewed the clinical charts of patients in whom therapeutic barium enema was performed for the control of diverticular bleeding between August 2010 and March 2012 at Yokohama Rosai Hospital. Twenty patients were included in the review, consisting of 14 men and 6 women. The median age of the patients was 73.5 years. The duration of the follow-up period ranged from 1 to 19 mo (median: 9.8 mo). Among the 20 patients were 11 patients who required the procedure for re-bleeding during hospitalization, 6 patients who required it for re-bleeding that developed after the patient left the hospital, and 3 patients who required the procedure for the prevention of re-bleeding. Barium (concentration: 150 w%/v%) was administered per the rectum, and the leading edge of the contrast medium was followed up to the cecum by fluoroscopy. After confirmation that the ascending colon and cecum were filled with barium, the enema tube was withdrawn, and the patient’s position was changed every 20 min for 3 h.

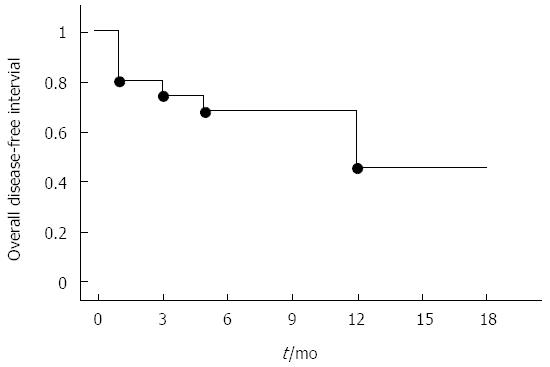

RESULTS: Twelve patients remained free of re-bleeding during the follow-up period (range: 1-19 mo) after the therapeutic barium enema, including 9 men and 3 women with a median age of 72.0 years. Re-bleeding occurred in 8 patients including 5 men and 3 women with a median age of 68.5 years: 4 developed early re-bleeding, defined as re-bleeding that occurs within one week after the procedure, and the remaining 4 developed late re-bleeding. The DFI (disease-free interval) decreased 0.4 for 12 mo. Only one patient developed a complication from therapeutic barium enema (colonic perforation).

CONCLUSION: Therapeutic barium enema is effective for the control of diverticular hemorrhage in cases where the active bleeding site cannot be identified by colonoscopy.

Core tip: In patients who present with diverticular bleeding, while endoscopic hemostasis is an effective treatment, the source of the bleeding is often difficult to identify because of massive bleeding and the presence of clots. We use therapeutic barium enema as a second-line treatment in cases where the source of bleeding cannot be identified by endoscopy. Therapeutic barium enema can be used relatively safely and has a low degree of invasiveness. When no other therapeutic techniques are available, therapeutic barium enema may be useful as a therapeutic alternative that can preclude the need for surgical treatment.

- Citation: Matsuura M, Inamori M, Nakajima A, Komiya Y, Inoh Y, Kawasima K, Naitoh M, Fujita Y, Eduka A, Kanazawa N, Uchiyama S, Tani R, Kawana K, Ohtani S, Nagase H. Effectiveness of therapeutic barium enema for diverticular hemorrhage. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(18): 5555-5559

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i18/5555.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i18.5555

In recent years, the overall prevalence of colonic diverticulosis has increased in Japan; this is likely caused by the shift to Westernized low-fiber diets[1]. In patients in Western countries, this disease usually affects the left side of the colon[2], whereas in patients in Eastern countries, diverticulosis is more common in the right hemicolon[3]. Although diverticular disease is actually uncommon in people under the age of 40, by the age of 50, almost one-third of the population develops diverticulosis[4].

Diverticula develop at sites of weaknesses in the colonic wall where the vasa recta penetrate the circular muscle layer[5]. As a diverticulum herniates, the vasa recta drape over the dome of the diverticulum and become susceptible to trauma and disruption[6].

Diverticular hemorrhage is the source of lower gastrointestinal bleeding in 17%-40% of adults, and thus, it is the most common cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. However, the exact cause of diverticular bleeding is not yet well understood[7]. Diverticula of the large intestine constitute a common source of lower gastrointestinal bleeding caused by the rupture of the underlying vasa recta[4,8]. A comparison of bleeding and non-bleeding diverticula has suggested the role of traumatic factors in the rendering of the vasa recta as prone to rupture and massive hemorrhage in the bleeding diverticula[6]. Although the cause of such trauma may be stercoral, little evidence has been found with respect to inflammation or diverticulitis[6].

More recent observations from the colonoscopic appearance of bleeding diverticula suggest that ulcerations or erosions at the neck or dome of the diverticula may be more frequent than was previously thought[9]. Bleeding has been observed to cease spontaneously in approximately 75% of undetected cases, but it is reported to recur in approximately half of these cases[10,11]. In cases with bleeding, endoscopic hemostasis is an effective treatment; however, it is often difficult to identify the source of bleeding because of massive bleeding and the presence of clots.

We use therapeutic barium enema as a treatment method in cases where the source of bleeding cannot be identified by endoscopy. In 1970, Adams[12] first reported the outcome of this treatment, but there have been few other reports of this method.

We present patients with colonic diverticular bleeding in whom the bleeding was successfully controlled by the newly designed barium impaction therapy using a high concentration of barium sulfate.

We reviewed the data of patients in whom therapeutic barium enema was performed for the control of diverticular bleeding between August 2010 and March 2012 at Yokohama Rosai Hospital. Twenty patients were included in the review, consisting of 14 men and 6 women. The median age of the patients was 73.5 years (range: 38-92 years). The duration of the follow-up period ranged from 1 to 19 mo (median: 9.8 mo).

Among the 20 cases were 11 cases in whom the procedure was performed for re-bleeding during hospitalization, 6 in whom it was performed for re-bleeding that developed after the patient left the hospital, and 3 cases in whom it was performed for the prevention of re-bleeding.

Pretreatment enforced the usual bowel evacuation before the therapeutic barium enema, or therapeutic barium enema therapy was undertaken on the day after the colonoscopy without bowel evacuation being enforced.

Barium (concentration: 150 w%/v%) was administered per the rectum, and the leading edge of the contrast medium was followed up to the cecum by fluoroscopy.

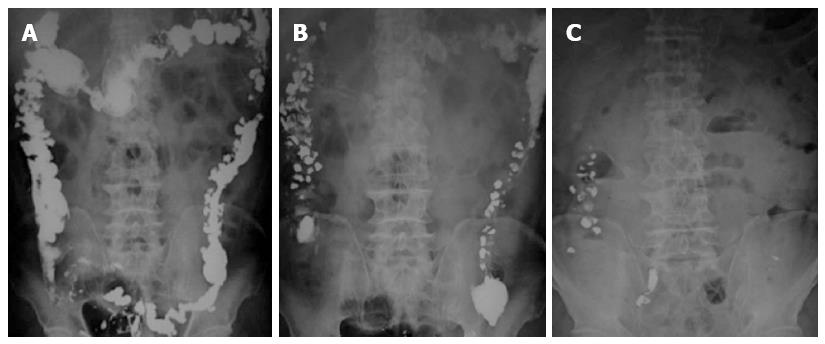

After confirmation that the ascending colon and cecum were filled with barium, the enema tube was withdrawn, and the patient’s position was changed every 20 min (i.e., prone, left lateral, supine and right lateral positions) for 3 h. We performed X-ray examinations during the follow-up to determine the extent of filling to the ascending colon and cecum (Figure 1).

Statistical evaluation was performed using Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher’s exact test. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with the StatView software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States). The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Masahiko Inamori from Yokohama City University Hospital.

The baseline characteristics of the study patients are summarized in Table 1. A total of 20 patients (14 men and 6 women; median age 73.5 years; range: 38-92 years) who were diagnosed with diverticular bleeding were enrolled in the study.

| Characteristics | n = 20 |

| Gender (M/F) | 14/6 |

| Age (mean ± SD, median: min-max) | 70.6 ± 12.5, 72.0: 39-92 |

| Taking anticoagulants | 9 |

| Taking NSAIDs | 2 |

Table 2 shows the current patients who exhibited bleeding and those who did not who were diagnosed with diverticular bleeding. These patients consisted of 12 non-bleeding patients (12/20; 60%), including 9 men and 3 women with a median age of 72.0 years. Six of these patients were taking anticoagulants, while none was taking NSAIDs.

| n = 20 | Non-bleeding | Re-bleeding | P value |

| (n = 12) | (n = 8) | ||

| Gender (M/F) | 9/3 | 5/3 | 0.6424 |

| Age (median: min-max) | 73.5: 54-90 | 68.5: 39-92 | 0.58851 |

| Taking anticoagulants | 6 | 3 | 0.6699 |

| Taking NSAIDs | 0 | 2 | 0.0007 |

By contrast, there were 8 patients who exhibited bleeding (8/20; 40%), including 5 men and 3 women with a median age of 68.5 years. Three of these patients were taking anticoagulants, while two were taking NSAIDs. Six patients had a history of previous bleeding.

Twelve patients remained free from re-bleeding during the follow-up period (range: 1-19 mo) after the therapeutic barium enema.

Re-bleeding occurred in 8 patients: 4 developed early re-bleeding, defined as re-bleeding that occurs within one week of the procedure, while the remaining 4 were diagnosed with late re-bleeding.

A significant difference was observed in the rate of re-bleeding between patients taking NSAIDs and those who were not (P = 0.0007).

Figure 2 shows the overall disease-free interval (DFI). The DFI decreased 0.4 for 12 mo. Only one patient developed a complication from therapeutic barium enema (colonic perforation).

In recent years, the prevalence of colonic diverticular diseases in Eastern countries, including Japan, has begun to increase. However, most of the reported cases of therapeutic barium enema are from Western countries[1].

Colonic diverticular disease exhibits mucosal outpouchings through the large intestine. Common complications of this disease are diverticular bleeding and diverticulitis. Diverticular bleeding is the most common source of acute severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding. It has been reported that acute lower intestinal bleeding occurs in 3%-5% of patients with colonic diverticula[2,13]. In most cases (70%-80%), diverticular bleeding stops spontaneously and resolves by itself[10]; however, bleeding may recur. Some patients require treatment with endoscopy, surgical operation and angiography to stop the bleeding.

Therapeutic colonoscopy may be useful when the location of acute diverticular bleeding can be identified. However, when the location of active bleeding cannot be discovered, therapeutic colonoscopy is unable to stop the bleeding, because diverticula are usually numerous and bleeding is intermittent. The identification of precise localization is very important for endoscopic treatment for diverticular bleeding.

There are case reports of the use of various colonoscopic techniques for the control of diverticular bleeding, including heater probes, epinephrine injection therapy, argon plasma coagulation, and endoclip application. In our 20 patients, it was difficult to identify the bleeding points, because colonoscopy revealed large amounts of blood in the colon and many diverticula with adherent blood clots. As an alternative therapeutic option, we performed therapeutic barium enema to control the bleeding in these patients.

There are some previous reports of the effect of barium on bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract[12,14]. The precise mechanism that underlies the effect of therapeutic barium enema remains unclear. Adams[12] mentioned two potential factors, namely, pressure by the barium solution that produces tamponade of the bleeding vessel and the direct hemostatic action of barium sulfate[15].

Table 2 shows non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use as a risk factor for re-bleeding in patients with colonic diverticular hemorrhage. In Western populations, in addition to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, antihypertensive medication and concomitant arteriosclerotic diseases have also been reported as risk factors for colonic diverticular hemorrhage[4,16]. A reason for the relationship between re-bleeding and NSAIDs was unclear, but we supposed intestinal mucosal damage by NSAIDs might cause re-bleeding. One of the limitations of our study is that the sample size was small, and a larger number of cases needs to be accumulated for future studies.

Although there have been a few reports of correlations between anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy and bleeding from colonic diverticula, no report was found regarding correlation between these therapies and re-bleeding[3,4,17].

Figure 2 shows that 60% of the patients in this study developed re-bleeding within 12-18 mo. McGuire reported that 38% of patients developed recurrent bleeding[10]. In another report of 83 patients with diverticular bleeding who were not treated, the predicted recurrence rate of bleeding was 9% at 1 year, 10% at 2 years, 19% at 3 years, and 25% at 4 years[18]. Our results, however, may be biased because most of the patients were over 80 years old or presented with severe bleeding.

Therapeutic barium enema can be used relatively safely and has a low degree of invasiveness. However, one of our 20 patients developed a complication (perforation) from the procedure. Therefore, the possibility of perforation must be considered, especially in patients with diverticulitis.

Therapeutic barium enema is effective for diverticular bleeding when the source of active diverticular bleeding is undiscovered by colonoscopy. When no other treatments are available, therapeutic barium enema may be useful as a therapeutic alternative that can preclude the need for surgical treatment.

Special thanks to the medical staff of the Hepatology and Gastroenterology, Yokohama City University Hospital, Kanagawa, Japan.

In patients presenting with diverticular bleeding, while endoscopic haemostasis is an effective treatment, the source of bleeding is often difficult to identify because of massive bleeding and the presence of clots. The authors use therapeutic barium enema as a treatment procedure of second choice in cases where the source of bleeding cannot be identified by endoscopy. The authors present patients with colonic diverticular bleeding in whom the bleeding was successfully controlled by the newly designed barium impaction therapy using a high concentration of barium sulfate.

Therapeutic barium enema can be used relatively safely and has a low degree of invasiveness. When no other therapeutic techniques are available, therapeutic barium enema may be useful as a therapeutic alternative that can preclude the need for surgical treatment.

Endoscopic treatment may be useful when the source of lower gastrointestinal bleeding is known. However, when the source of bleeding cannot be identified or if multiple sites of bleeding are found, endoscopic treatment is unable to stop the bleeding. Therapeutic barium enema is effective for diverticular hemorrhage when the active bleeding site cannot be identified by colonoscopy. The authors present patients with colonic diverticular bleeding in whom the bleeding was successfully controlled by the newly designed barium impaction therapy using a high concentration of barium sulfate.

Therapeutic barium enema is effective for diverticular hemorrhage when the active bleeding site cannot be identified by colonoscopy. When no other therapeutic techniques are available, therapeutic barium enema may be useful as a therapeutic alternative that can preclude the need for surgical treatment.

Diverticula develop at sites of weaknesses in the colonic wall where the vasa recta penetrate the circular muscle layer. As a diverticulum herniates, the vasa recta drape over the dome of the diverticulum and become susceptible to trauma and disruption. Diverticular hemorrhage is the source of lower gastrointestinal bleeding in 17%-40% of adults, and thus, it is the most common cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

The report describes the usefulness of therapeutic barium enema procedure in preventing bleeding from colonic diverticula.

P- Reviewer: Abdel-Salam OME, Lee SH, Sugimoto M S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Logan S E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Nakaji S, Sugawara K, Saito D, Yoshioka Y, MacAuley D, Bradley T, Kernohan G, Baxter D. Trends in dietary fiber intake in Japan over the last century. Eur J Nutr. 2002;41:222-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Stollman NH, Raskin JB. Diverticular disease of the colon. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29:241-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yamada A, Sugimoto T, Kondo S, Ohta M, Watabe H, Maeda S, Togo G, Yamaji Y, Ogura K, Okamoto M. Assessment of the risk factors for colonic diverticular hemorrhage. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:116-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lewis M. Bleeding colonic diverticula. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:1156-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Meyers MA, Volberg F, Katzen B, Alonso D, Abbott G. The angioarchitecture of colonic diverticula. Significance in bleeding diverticulosis. Radiology. 1973;108:249-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Meyers MA, Alonso DR, Gray GF, Baer JW. Pathogenesis of bleeding colonic diverticulosis. Gastroenterology. 1976;71:577-583. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Suzuki K, Uchiyama S, Imajyo K, Tomeno W, Sakai E, Yamada E, Tanida E, Akiyama T, Watanabe S, Endo H. Risk factors for colonic diverticular hemorrhage: Japanese multicenter study. Digestion. 2012;85:261-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Saito K, Inamori M, Sekino Y, Akimoto K, Suzuki K, Tomimoto A, Fujisawa N, Kubota K, Saito S, Koyama S. Management of acute lower intestinal bleeding: what bowel preparation should be required for urgent colonoscopy? Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:1331-1334. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Foutch PG. Diverticular bleeding: are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs risk factors for hemorrhage and can colonoscopy predict outcome for patients? Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1779-1784. [PubMed] |

| 10. | McGuire HH. Bleeding colonic diverticula. A reappraisal of natural history and management. Ann Surg. 1994;220:653-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Koperna T, Kisser M, Reiner G, Schulz F. Diagnosis and treatment of bleeding colonic diverticula. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:702-705. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Adams JT. Therapeutic barium enema for massive diverticular bleeding. Arch Surg. 1970;101:457-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McGuire HH, Haynes BW. Massive hemorrhage for diverticulosis of the colon: guidelines for therapy based on bleeding patterns observed in fifty cases. Ann Surg. 1972;175:847-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Miller RE, Skucas J, Violante MR, Shapiro ME. The effect of barium on blood in the gastrointestinal tract. Radiology. 1975;117:527-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Iwamoto J, Mizokami Y, Shimokobe K, Matsuoka T, Matsuzaki Y. Therapeutic barium enema for bleeding colonic diverticula: four case series and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6413-6417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Strate LL, Liu YL, Aldoori WH, Syngal S, Giovannucci EL. Obesity increases the risks of diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:115-122.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nagata N, Niikura R, Aoki T, Shimbo T, Kishida Y, Sekine K, Tanaka S, Watanabe K, Sakurai T, Yokoi C. Colonic diverticular hemorrhage associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, low-dose aspirin, antiplatelet drugs, and dual therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1786-1793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Longstreth GF. Epidemiology and outcome of patients hospitalized with acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:419-424. [PubMed] |