Published online May 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i17.5328

Peer-review started: November 17, 2014

First decision: December 11, 2014

Revised: January 21, 2015

Accepted: February 11, 2015

Article in press: February 11, 2015

Published online: May 7, 2015

Processing time: 177 Days and 9.2 Hours

AIM: To assess the sampling quality of four different forceps (three large capacity and one jumbo) in patients with Barrett’s esophagus.

METHODS: This was a prospective, single-blind study. A total of 37 patients with Barrett’s esophagus were enrolled. Targeted or random biopsies with all four forceps were obtained from each patient using a diagnostic endoscope during a single endoscopy. The following forceps were tested: A: FB-220K disposable large capacity; B: BI01-D3-23 reusable large capacity; C: GBF-02-23-180 disposable large capacity; and jumbo: disposable Radial Jaw 4 jumbo. The primary outcome measurement was specimen adequacy, defined as a well-oriented biopsy sample 2 mm or greater with the presence of muscularis mucosa.

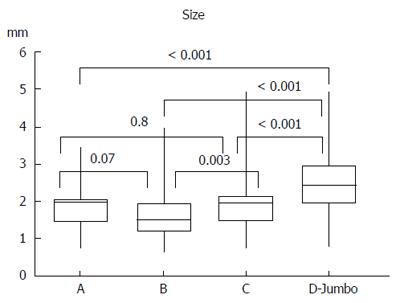

RESULTS: A total of 436 biopsy samples were analyzed. We found a significantly higher proportion of adequate biopsy samples with jumbo forceps (71%) (P < 0.001 vs forceps A: 26%, forceps B: 17%, and forceps C: 18%). Biopsies with jumbo forceps had the largest diameter (median 2.4 mm) (P < 0.001 vs forceps A: 2 mm, forceps B: 1.6 mm, and forceps C: 2mm). There was a trend for higher diagnostic yield per biopsy with jumbo forceps (forceps A: 0.20, forceps B: 0.22, forceps C: 0.27, and jumbo: 0.28). No complications related to specimen sampling were observed with any of the four tested forceps.

CONCLUSION: Jumbo biopsy forceps, when used with a diagnostic endoscope, provide more adequate specimens as compared to large-capacity forceps in patients with Barrett’s esophagus.

Core tip: Good quality biopsy specimens are required for reliable diagnosis of early neoplasia in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. It remains controversial whether the use of jumbo forceps provides an advantage over large-capacity forceps. We compared the sampling quality using four different biopsy forceps. Biopsies were obtained using a diagnostic endoscope during a single endoscopy. We found a significantly higher proportion of adequate biopsy samples with jumbo forceps as compared to the three large capacity forceps. Thus, jumbo biopsy forceps, when used with a diagnostic endoscope, provide more adequate specimen as compared to large-capacity forceps.

- Citation: Martinek J, Maluskova J, Stefanova M, Tuckova I, Suchanek S, Vackova Z, Krajciova J, Kollar M, Zavoral M, Spicak J. Improved specimen adequacy using jumbo biopsy forceps in patients with Barrett's esophagus. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(17): 5328-5335

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i17/5328.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i17.5328

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is a precancerous lesion, and the patients with BE should be included in surveillance programs involving regular endoscopic examinations with biopsies. The aim of such surveillance is an early detection of intraepithelial neoplasia (IEN) or cancer[1]. If detected early, IEN or esophageal adenocarcinoma can completely be cured using endoscopic methods such as endoscopic resection and ablation. For patients with BE without IEN, a surveillance endoscopy with four-quadrant biopsies at 2-cm intervals performed every three to five years is commonly recommended, though it is not evidence based[2]. Despite the promising results of advanced imaging modalities with targeted biopsies[3], a traditional protocol with random biopsies is presently considered as the gold standard for BE surveillance[4].

For biopsy, the choice of forceps has traditionally been among standard, large-capacity, or jumbo forceps. While the standard and large-capacity forceps are used with a standard diagnostic endoscope, the jumbo forceps are recommended for use with a therapeutic endoscope with a larger (3.2 mm) channel. However, the new Radial Jaw 4 (RJ4; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, United States) jumbo forceps have been successfully tested with standard diagnostic endoscope[5-7].

Most of the studies found jumbo forceps superior to standard or large capacity forceps in terms of specimen quality, adequacy, or diagnostic yield[5,6,8-10]. A recent study challenged the requirement for jumbo forceps over large-capacity forceps in patients with BE[11]. The authors found similar rates of adequate specimens with the large-capacity forceps (used with a diagnostic endoscope) when compared with the jumbo forceps (used with a therapeutic endoscope). The insufficient quality of biopsy specimen collected by jumbo forceps used with a therapeutic endoscope can be explained by the fact that maneuvering and taking biopsies from the esophagus with a larger therapeutic endoscope are more difficult as compared to a standard endoscope.

Here we present a study comparing the performances of three types of large-capacity forceps and one type of jumbo forceps (all forceps were used with a diagnostic endoscope) in terms of quality of biopsy specimen in patients with BE. We hypothesized that the use of jumbo forceps with a diagnostic endoscope provides more adequate specimens compared to large-capacity forceps.

The study was begun in January 2012 at the University Military Hospital in Prague, but later completed in the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine in Prague, where the principal investigator moved in November 2012. The study was continued through March 2013. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of both institutions. Neither financial support nor any free commercial devices were received.

This was a prospective clinical trial. Two experienced physicians performed all endoscopic examinations. They were not blinded because the four types of forceps are visually different; however, the two pathologists, who evaluated the histologic specimens, were blinded with respect to the type of forceps used. For collecting biopsy specimens, all four tested forceps were used in a random order in each patient (the order of the four tested forceps was provided in a sealed opaque envelope for each patient before starting the endoscopy).

All consecutive patients examined in our department during the study period, with endoscopic finding of BE with a metaplastic segment longer than 2 cm, were invited to participate. Although a total of 51 patients matching the inclusion criteria were invited, 37 patients were finally enrolled in the study. All the participants provided informed written consent. Exclusion criteria include: inability to give informed consent, prominent or depressed macroscopically visible lesion (exception being the patients with flat lesions of type 0-IIb), an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with biopsies two months prior to enrollment, esophagitis, previous diagnosis of esophageal carcinoma, previous endoscopic resection or ablation therapy, participation in another clinical trial, esophageal varices, and treatment with anticoagulants (the use of antiplatelet agents was permitted).

Following are the four different types of forceps (with spikes) used for this study: A: FB-220K large capacity disposable biopsy forceps (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) with an outer diameter of 2.45 mm; B: BI01-D3-23 large capacity reusable biopsy forceps (Medwork, GmbH, Höchstadt/Aisch, Germany) with an outer diameter of 2.3 mm; C: GBF-02-23-180 large capacity disposable biopsy forceps (Medi-Globe GmbH, Rosenheim, Germany) with an outer diameter of 2.3 mm; and jumbo: RJ4 disposable jumbo biopsy forceps with an outer diameter of 2.84 mm. The RJ4 jumbo forceps can safely be used with a standard diagnostic endoscope (Figure 1).

All endoscopies were performed using a diagnostic endoscope (GIF FQ 260 Z, Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). An intravenous sedation with midazolam (3-5 mg) was administered if judged necessary. BE was classified using the Prague C and M criteria. For reliable detection of suspect areas or visible lesions, the whole esophagus was first flushed with water, followed by the careful examination with tri-modal imaging (autofluorescence, narrow-band imaging, high-resolution endoscopy).

According to the length of the Barrett’s segment, the total number of biopsies was estimated and consequently, the approximate number of biopsies to be taken with each forceps was determined. For example, in a patient with BE C6M6, the total estimated number of biopsies was 16 (four biopsies each at 0 cm, 2 cm, 4 cm, and 6 cm). Therefore, four biopsies were taken by each of the tested forceps; the first set of four biopsies was taken with one forceps, followed by a second set of four biopsies taken with another forceps, etc.

In patients with a visible lesion (type 0-IIb) or mucosal irregularities, the targeted biopsies only were taken in separate containers. In patients without targeted biopsies, standard random four-quadrant biopsy samples according to the Seattle protocol were obtained for every 2 cm for the entire length of BE. Biopsies were started at the gastroesophageal junction and then continued proximally. Thus, we performed part of the Seattle protocol with each forceps in turn.

The specimens were collected in separate containers according to the type of forceps (every container contained specimens taken by only one type of forceps) and the level of esophagus.

The biopsies were taken using a “turn and suck” technique. After the esophageal mucosa was positioned in front of the endoscope, the forceps were opened, and the suction was applied. Thereafter, the forceps were closed, suction was revealed, and after the visual control, specimens were finally taken one at a time. The biopsy tissues were formalin fixed and processed for paraffin embedding. Specimens were not mounted before immersion fixation. Five-micron tissue sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathologic evaluation.

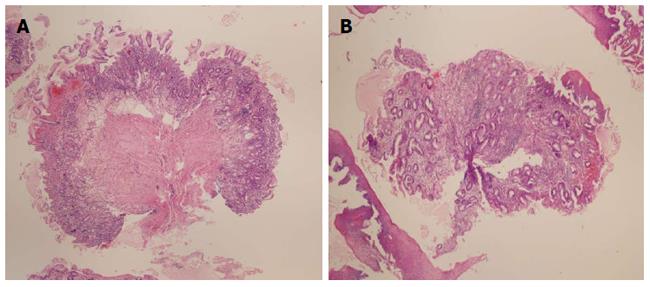

Two expert pathologists independently evaluated each sample and settled all discrepancies by consensus. For each biopsy specimen, the following data were collected: size including the largest diameter, deepest tissue layer present, and quality of specimen orientation. Good orientation was defined as having two or more tissue layers with correct depth order in linear fashion. The histopathologic diagnosis of each specimen was recorded along with the presence or the absence of intestinal metaplasia. Additionally, we also recorded the overall diagnosis for each patient based on the highest degree of intraepithelial neoplasia.

We used the same definition of the primary outcome as was used by Gonzalez et al[11], and the authors defined the primary outcome as the specimen adequacy for histologic assessment; an adequate biopsy sample was defined a priori as a well-oriented specimen of 2 mm or greater diameter with at least the presence of muscularis mucosa. Secondary outcomes included detection of intestinal metaplasia and/or intraepithelial neoplasia (diagnostic yield) and adverse events.

Data are presented as mean ± SD or median with ranges or appropriate percentiles. The four forceps were compared by performing the overall Fisher’s exact tests for categorical data, analysis of variance for normally distributed data, and Kruskal-Wallis tests for non-normally distributed data. Normality was assessed by the Skewness-Kurtosis test. If the overall testing showed a significant difference among groups (P < 0.05), then pair-wise comparisons between groups were performed by using the Fisher’s exact test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (n = 6, statistical significance for pair-wise comparisons was defined as P < 0.008). Overall diagnostic yield (per biopsy analysis) was calculated as the number of biopsy samples with IEN divided by the total number of biopsy specimens obtained with the respective forceps.

In this study, at least 90 biopsies were taken by each forceps for detecting 15% difference between any two forceps in main outcome parameter (specimen adequacy) with study power of 80% and overall significance level of P < 0.05.

A total of 37 patients with a median age of 61 years (range: 27-72 years, male: 31, female: 6) were enrolled in the study. The median length of BE segment was 6 cm (range: 2-12 cm). All endoscopies were performed as an outpatient procedure without adverse events such as bleeding or perforations, and the patients did not experience any delayed complications such as bleeding. All minor bleedings after biopsies resolved spontaneously. Patients did not complain of any pain or increased discomfort during or after the procedure.

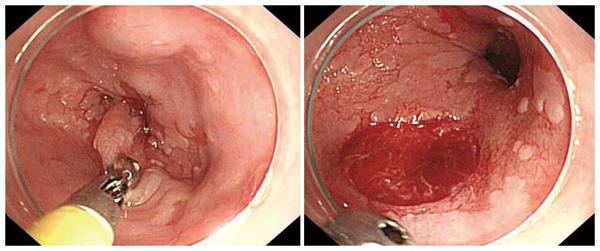

Neither of the endoscopists experienced any problems getting through the diagnostic channel with the jumbo RJ4 forceps; there was sufficient space around the forceps (Figure 1). One issue we found while taking the biopsies with jumbo forceps was that often, large mucosal defects were created in the esophagus, even though clinically the patients did not come to harm (Figure 2).

Table 1 and Figure 3 present the summaries of the principal results. A total of 436 biopsies were taken; this represents on average 11.8 biopsies per patient (range: 4-25).

More than two-thirds of biopsies taken with jumbo forceps, were adequate (71%), which was significantly more compared to the large-capacity forceps (P < 0.001). Muscularis mucosae were present in 80% of the samples obtained by jumbo forceps. We obtained significantly larger specimens (2.4 mm) using the jumbo forceps (P < 0.001 vs large-capacity forcepts). Specimens taken with jumbo forceps and large-capacity forceps A and C were well-oriented in 60%-70% of samples, whereas 66% of specimens obtained with forceps B were not well-oriented. Figure 4 presents the photomicrographs of adequate and inadequate biopsy samples.

Intestinal metaplasia was detected in all patients, but not in all (89%) biopsy specimens. Thirteen patients (35%) had BE without IEN, whereas low-grade IEN was detected in 20 (54%) and high-grade IEN was detected in four patients (11%). Despite the trend for a higher diagnostic yield with jumbo forceps, we did not find any significant differences in detecting intestinal metaplasia or IEN among the four studied forceps (Table 2).

| Variable | Total(n = 436) | Forceps type | |||

| Large-capacity | Jumbo(n = 92) | ||||

| A(n = 121) | B(n = 115) | C(n = 108) | |||

| Intestinal metaplasia | 386 (89) | 103 (85) | 99 (86) | 98 (91) | 86 (93) |

| No IEN | 332 (76) | 97 (80) | 90 (78) | 79 (73) | 66 (72) |

| Low-grade IEN | 91 (21) | 22 (18) | 22 (19) | 26 (24) | 21 (23) |

| High-grade IEN | 13 (3) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 5 (5) |

| Diagnostic yield (per biopsy) | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.28 |

In this study, we obtained a significantly higher proportion of adequate biopsy samples with jumbo RJ4 forceps as compared to the biopsy specimens obtained with the other three large-capacity forceps. Larger specimens containing muscularis mucosae (in 80% of samples) were obtained using the jumbo forceps; among the collected specimens, 77% were well-oriented. We chose a percentage of adequate specimens defined a priori as the main outcome parameter, similar to other studies comparing standard, large-capacity, and jumbo (RJ4) forceps[11]. Surprisingly, in this study, the authors found that standard or large-capacity forceps produced adequate specimens in 38% and 32% of samples, respectively, which were significantly more than the samples collected with RJ4 jumbo forceps used with a therapeutic endoscope (25%). The specimens obtained with jumbo forceps had the largest diameter but the lowest proportion of well-oriented specimens (44%)[11].

Many other studies have reported that jumbo forceps collect superior quality biopsy specimens compared to standard or large-capacity forceps[5,6,8-10]. Jumbo forceps (RJ4) is superior than other types of forceps in terms of the followings factors: (1) in obtaining adequate surveillance biopsies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease[8]; (2) in obtaining accurate diagnosis of submucosal lesion[6]; (3) in removing small, sessile colorectal polyps[9]; and (4) in tissue acquisition in patients with BE[5,10]. In the study by Komanduri et al[5], RJ4 jumbo forceps provided 79% adequate samples and large-capacity forceps collected 16% of adequate samples.

Similar to our study, there have been two other studies[5,11] comparing the performance of RJ4 jumbo forceps with other forceps; however, different types of endoscopes were used for biopsies with jumbo forceps. As with the present study, Komanduri et al[5] studied the performance of RJ4 jumbo forceps with a standard diagnostic endoscope (channel 2.8 mm) and obtained 79% adequate samples. On the other hand, Gonzalez et al[11] examined RJ4 jumbo forceps with a therapeutic endoscope with a larger channel (3.2 mm), but obtained only 25% adequate samples. Manipulation and maneuvering with a therapeutic endoscope in the esophagus is difficult compared to a standard endoscope. The “turn and suck technique” requires directing the tip of the endoscope against the esophageal wall in an appropriate angle; for a therapeutic endoscope, such alignment is more problematic. This might explain the higher percentage of biopsy specimens with an improper orientation (and consequently the low percentage of adequate samples) in the study by Gonzalez et al[11].

Jumbo forceps have traditionally been recommended for use with therapeutic endoscopes, which was the basis of the original Seattle biopsy protocol[12]. However, similar to our study, there are two other reports where the authors also used RJ4 jumbo forceps successfully with a standard diagnostic endoscope[5-6], and we, like others, did not experience any difficulties in introducing the jumbo forceps through the smaller channel.

The main aim of the surveillance of patients with BE is the early detection of IEN or esophageal adenocarcinoma, allowing less-invasive endoscopic treatment. Although any benefit has yet to be demonstrated in a randomized control trial (one is underway in the UK at this time), endoscopic surveillance is recommended. Nevertheless, several studies have suggested that patients with BE who undergo surveillance benefit from early-stage cancer diagnosis and improved survival[13-15]; however, no association was found between reduced risk of death from esophageal adenocarcinoma and endoscopic surveillance[16].

The surveillance of patients with BE is still based on random four-quadrant biopsies every 1-2 cm with large-capacity forceps performed every 3-5 years[2]. Although the type of forceps undoubtedly influences specimen adequacy, a majority of available guidelines do not recommend any particular type of forceps to be used for surveillance biopsies[1,4,17]. The random biopsy protocol is time consuming, and an increasing length of BE segment decreases physician adherence to the protocol[18]. Therefore, multiple modern advanced imaging modalities (e.g., narrow-band imaging) have been developed and tested to allow targeted biopsy strategies, which have been shown to increase the diagnostic yield of BE neoplasia[3,19]. Despite these results, a random biopsy protocol still remains the gold standard of care with patients with BE, and all recent guidelines recommend strict adherence to this protocol.

The key question is whether a more adequate biopsy specimen increases the detection of IEN. Komanduri et al[5] demonstrated that the use of RJ4 jumbo forceps improved the detection of IEN. Gonzalez et al[11] did not compare the diagnostic yields of three types of forceps (every patient underwent biopsy with only one type of forceps). Our study was not primarily designed to compare the diagnostic yield among the tested forceps. At present, there is no clear evidence to establish that improving specimen adequacy increases detection of IEN. Although not evidence based, a more adequate specimen is likely to yield better diagnostic accuracy. Larger-sized specimens provide a larger surface area for examination, which might lead to an increased likelihood in detecting neoplastic changes.

Specimen adequacy is also an important issue in patients undergoing post-radiofrequency ablation surveillance. One study (with large-capacity forceps) demonstrated insufficient specimen adequacy, as a majority of samples did not contain subepithelial structures[20]. The second study (with jumbo forceps) found that almost 80% of samples were adequate for evaluation of subsquamous buried glands[21]. These results also suggest a superiority of jumbo forceps in patients undergoing esophageal biopsy.

There have been concerns about the safety of using a jumbo forceps. A large proportion of patients (35%) experienced significant bleeding after biopsy with jumbo forceps for subepithelial lesions[6]. However, in patients with BE, neither severe bleeding nor other serious adverse events have been reported with jumbo forceps[5,11,12]. In our study, none of the patients experienced any significant bleeding after any biopsy nor any other adverse events. There is only one published case report of severe life-threatening bleeding following BE surveillance biopsies so far; the report did not mention the type of the forceps used[22].

The current study has several limitations. Firstly, we investigated specimen adequacy as a primary endpoint and diagnostic yield as a secondary outcome. Second, there was a selection bias; we detected a high proportion of patients with IEN (both low and high grade IEN; 65%). Our department is a referral center providing endoscopic treatment for patients with BE; hence, this explains higher percentage of patients with IEN as compared to other studies (19%[5], 40%[11], and 49%[19]). In addition, the use of tri-modal endoscopy with targeted biopsies (in some patients) may also explain the higher frequency of IEN detection. However, the selection bias did not influence our primary endpoint in any way. Third, the endoscopists were not blinded with respect to forceps (all forceps are visually different).

In summary, to obtain diagnostically adequate biopsy specimens in patients with BE, the jumbo biopsy forceps, when used with a standard diagnostic endoscope, showed superior performance compared to the other three studied large-capacity forceps.

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is defined as the replacement of distal esophageal squamous mucosa with metaplastic columnar epithelium. Patients with BE have an increased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Therefore, most guidelines recommend surveillance endoscopy every 2-5 years with targeted and random esophageal biopsies to detect early neoplastic lesions (intraepithelial neoplasia or early cancer). If detected early, esophageal neoplasia can be managed endoscopically.

Tissue sampling in patients with BE should be performed by using jumbo or large-capacity biopsy forceps. A majority of studies found an advantage of jumbo forceps compared to large-capacity or standard forceps with regard to specimen adequacy. However, the advantage of jumbo forceps has recently been challenged, especially due to improper orientation of specimens. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that jumbo Radial Jaw 4 (RJ4) forceps, if used with a standard diagnostic endoscope, provide more adequate specimens compared to large-capacity forceps.

The authors found that jumbo RJ4 forceps achieved adequate specimen in 71% of samples. On the other hand, three types of large-capacity forceps achieved adequate specimen in only 17%-26% of samples. There was a trend for higher diagnostic yield with jumbo forceps.

Based on these findings, the present study recommend the use of RJ4 jumbo forceps for surveillance endoscopy in patients with BE. Further studies should investigate whether better specimen adequacy implies improved detection of intraepithelial neoplasia.

Specimen adequacy was defined as a well-oriented biopsy sample 2 mm or greater with the presence of muscularis mucosa.

The authors compared four different forceps for retrieving biopsies from patients with BE. The study appears to be well designed and conducted, and the article is clearly presented.

P- Reviewer: Brusselaers N S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: AmEditor E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Spechler SJ, Sharma P, Souza RF, Inadomi JM, Shaheen NJ. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of Barrett‘s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1084-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 382] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Evans JA, Early DS, Fukami N, Ben-Menachem T, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Decker GA, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Foley KQ. The role of endoscopy in Barrett’s esophagus and other premalignant conditions of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:1087-1094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Canto MI, Anandasabapathy S, Brugge W, Falk GW, Dunbar KB, Zhang Z, Woods K, Almario JA, Schell U, Goldblum J. In vivo endomicroscopy improves detection of Barrett’s esophagus-related neoplasia: a multicenter international randomized controlled trial (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:211-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K, Ang Y, Kang JY, Watson P, Trudgill N, Patel P, Kaye PV, Sanders S. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2014;63:7-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1016] [Cited by in RCA: 875] [Article Influence: 79.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Komanduri S, Swanson G, Keefer L, Jakate S. Use of a new jumbo forceps improves tissue acquisition of Barrett’s esophagus surveillance biopsies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1072-8.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Buscaglia JM, Nagula S, Jayaraman V, Robbins DH, Vadada D, Gross SA, DiMaio CJ, Pais S, Patel K, Sejpal DV. Diagnostic yield and safety of jumbo biopsy forceps in patients with subepithelial lesions of the upper and lower GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:1147-1152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Korst RJ, Santana-Joseph S, Rutledge JR, Antler A, Bethala V, DeLillo A, Kutner D, Lee BE, Pazwash H, Pittman RH. Patterns of recurrent and persistent intestinal metaplasia after successful radiofrequency ablation of Barrett’s esophagus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:1529-1534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Elmunzer BJ, Higgins PD, Kwon YM, Golembeski C, Greenson JK, Korsnes SJ, Elta GH. Jumbo forceps are superior to standard large-capacity forceps in obtaining diagnostically adequate inflammatory bowel disease surveillance biopsy specimens. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:273-278; quiz 334, 336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Draganov PV, Chang MN, Alkhasawneh A, Dixon LR, Lieb J, Moshiree B, Polyak S, Sultan S, Collins D, Suman A. Randomized, controlled trial of standard, large-capacity versus jumbo biopsy forceps for polypectomy of small, sessile, colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:118-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Falk GW, Rice TW, Goldblum JR, Richter JE. Jumbo biopsy forceps protocol still misses unsuspected cancer in Barrett‘s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:170-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gonzalez S, Yu WM, Smith MS, Slack KN, Rotterdam H, Abrams JA, Lightdale CJ. Randomized comparison of 3 different-sized biopsy forceps for quality of sampling in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:935-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Levine DS, Blount PL, Rudolph RE, Reid BJ. Safety of a systematic endoscopic biopsy protocol in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1152-1157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wong T, Tian J, Nagar AB. Barrett‘s surveillance identifies patients with early esophageal adenocarcinoma. Am J Med. 2010;123:462-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Corley DA, Levin TR, Habel LA, Weiss NS, Buffler PA. Surveillance and survival in Barrett’s adenocarcinomas: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:633-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in RCA: 341] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fitzgerald RC, Saeed IT, Khoo D, Farthing MJ, Burnham WR. Rigorous surveillance protocol increases detection of curable cancers associated with Barrett’s esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:1892-1898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Corley DA, Mehtani K, Quesenberry C, Zhao W, de Boer J, Weiss NS. Impact of endoscopic surveillance on mortality from Barrett’s esophagus-associated esophageal adenocarcinomas. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:312-319.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schafer TW, Hollis-Perry KM, Mondragon RM, Brann OS. An observer-blinded, prospective, randomized comparison of forceps for endoscopic esophageal biopsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:192-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Abrams JA, Kapel RC, Lindberg GM, Saboorian MH, Genta RM, Neugut AI, Lightdale CJ. Adherence to biopsy guidelines for Barrett’s esophagus surveillance in the community setting in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:736-742; quiz 710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sharma P, Hawes RH, Bansal A, Gupta N, Curvers W, Rastogi A, Singh M, Hall M, Mathur SC, Wani SB. Standard endoscopy with random biopsies versus narrow band imaging targeted biopsies in Barrett’s oesophagus: a prospective, international, randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2013;62:15-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gupta N, Mathur SC, Dumot JA, Singh V, Gaddam S, Wani SB, Bansal A, Rastogi A, Goldblum JR, Sharma P. Adequacy of esophageal squamous mucosa specimens obtained during endoscopy: are standard biopsies sufficient for postablation surveillance in Barrett’s esophagus? Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:11-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shaheen NJ, Peery AF, Overholt BF, Lightdale CJ, Chak A, Wang KK, Hawes RH, Fleischer DE, Goldblum JR. Biopsy depth after radiofrequency ablation of dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:490-496.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mannath J, Subramanian V, Kaye PV, Ragunath K. Life-threatening bleeding following Barrett’s surveillance biopsies. Endoscopy. 2010;42 Suppl 2:E211-E212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |