Published online Apr 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4620

Peer-review started: October 4, 2014

First decision: October 29, 2014

Revised: November 11, 2014

Accepted: January 8, 2015

Article in press: January 8, 2015

Published online: April 21, 2015

Processing time: 198 Days and 17.2 Hours

AIM: To investigate the impact of surgical procedures on prognosis of gallbladder cancer patients classified with the latest tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system.

METHODS: A retrospective study was performed by reviewing 152 patients with primary gallbladder carcinoma treated at Peking Union Medical College Hospital from January 2003 to June 2013. Postsurgical follow-up was performed by telephone and outpatient visits. Clinical records were reviewed and patients were grouped based on the new edition of TNM staging system (AJCC, seventh edition, 2010). Prognoses were analyzed and compared based on surgical operations including simple cholecystectomy, radical cholecystectomy (or extended radical cholecystectomy), and palliative surgery. Simple cholecystectomy is, by definition, resection of the gallbladder fossa. Radical cholecystectomy involves a wedge resection of the gallbladder fossa with 2 cm non-neoplastic liver tissue; resection of a suprapancreatic segment of the extrahepatic bile duct and extended portal lymph node dissection may also be considered based on the patient’s circumstance. Palliative surgery refers to cholecystectomy with biliary drainage. Data analysis was performed with SPSS 19.0 software. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Logrank test were used for survival rate comparison. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

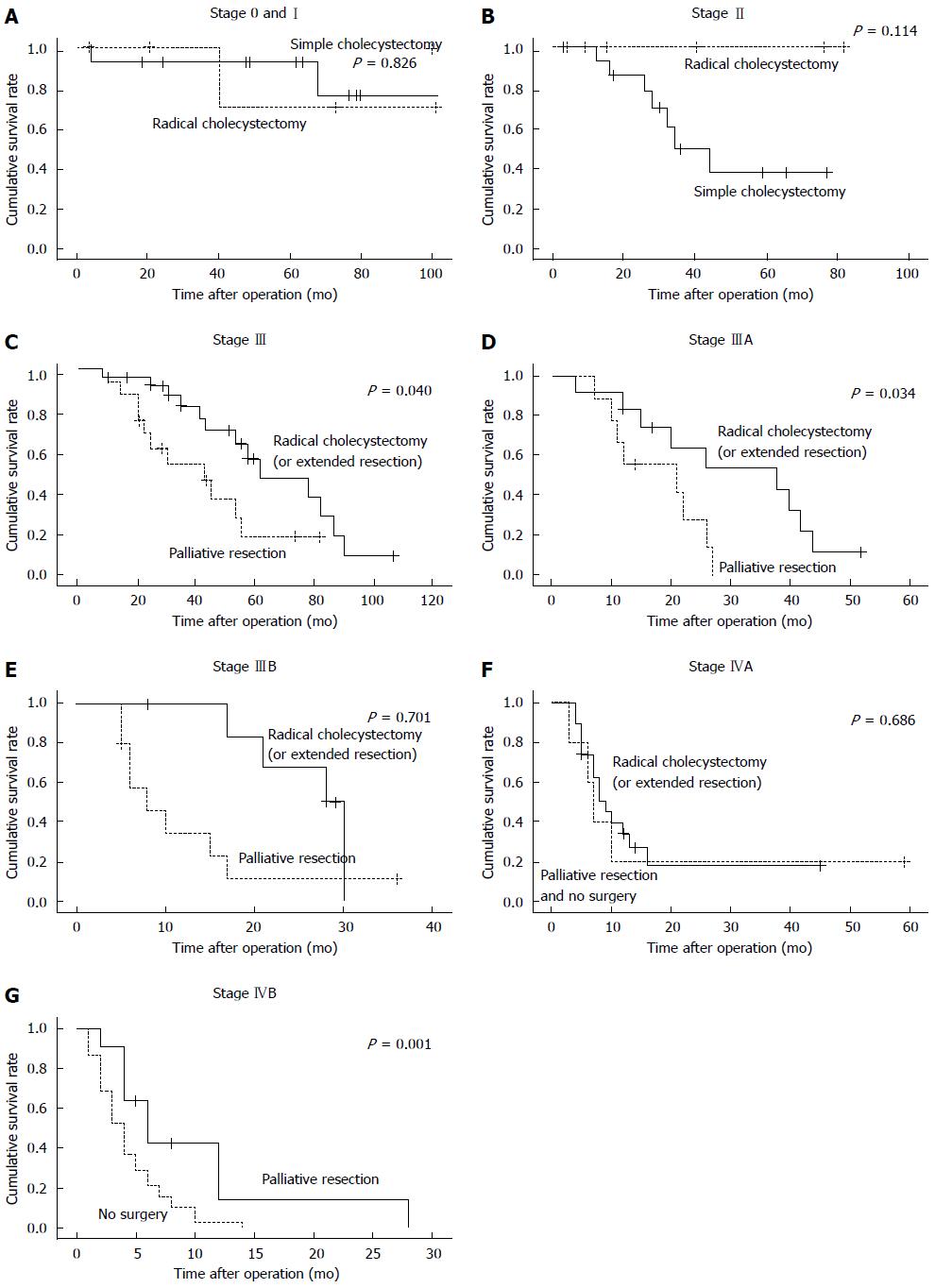

RESULTS: Patients were grouped based on the new 7th edition of TNM staging system, including 8 cases of stage 0, 10 cases of stage I, 25 cases of stage II, 21 cases of stage IIIA, 21 cases of stage IIIB, 24 cases of stage IVA, 43 cases of stage IVB. Simple cholecystectomy was performed on 28 cases, radical cholecystectomy or expanded gallbladder radical resection on 57 cases, and palliative resection on 28 cases. Thirty-nine cases were not operated. Patients with stages 0 and I disease demonstrated no statistical significant difference in survival time between those receiving radical cholecystectomy and simple cholecystectomy (P = 0.826). The prognosis of stage II patients with radical cholecystectomy was better than that of simple cholecystectomy. For stage III patients, radical cholecystectomy was significantly superior to other surgical options (P < 0.05). For stage IVA patients, radical cholecystectomy was not better than palliative resection and non-surgical treatment. For stage IVB, patients who underwent palliative resection significantly outlived those with non-surgical treatment (P < 0.01)

CONCLUSION: For stages 0 and I patients, simple cholecystectomy is the optimal surgical procedure, while radical cholecystectomy should be actively operated for stages II and III patients.

Core tip: Surgical resection is still the only cure for gallbladder cancer. Choice of surgery procedure based upon disease stages remains an important topic. This study showed that simple cholecystectomy would be the best choice for stages 0 and I gallbladder cancer (GBC) patients; stages II and III patients should actively seek for radical cholecystectomy (or extended radical resection surgery); and palliative treatment should be the major method for patients with stage IV GBC, and careful evaluation was necessary before applying any more aggressive surgical procedure.

- Citation: He XD, Li JJ, Liu W, Qu Q, Hong T, Xu XQ, Li BL, Wang Y, Zhao HT. Surgical procedure determination based on tumor-node-metastasis staging of gallbladder cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(15): 4620-4626

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i15/4620.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4620

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is the most common and aggressive malignant disease in the biliary system[1]. With the development of imaging technique in recent years, more and more GBC cases were diagnosed[2]. However, due to the lack of specific signs and symptoms, most of the cases were either diagnosed incidentally or at an advanced stage, which led to poor prognosis[3]. Advanced GBC is characterized by local invasion, extensive regional lymph node metastasis, vascular encasement, and distant metastases. Interdisciplinary collaboration among surgeons, oncologists, and endoscopy experts in the treatment of GBC patients is very important[4]. Surgical resection is still the only chance for cure, yet the prognosis is poor due to high recurrence, morbidity and mortality[5-7]. Choice of surgery procedure based upon disease stages remains an important topic. Currently no guidelines have been established for the treatment of GBC. Surgical management of GBC that had been documented from different countries or areas demonstrated different results of prognosis[8]. This retrospective study aimed to assess the surgical approaches and patient prognosis based on the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system (AJCC, seventh edition, 2010)[9] in the Chinese population, seeking to generalize an effective strategy that could be suitable for the majority of patients.

Postsurgical follow-up was performed by telephone and outpatient visits on 152 GBC patients who were treated from January 2003 to June 2013 at the Peking Union Medical College Hospital. Clinical records were reviewed and patients were re-grouped based on the new edition of TNM staging system (AJCC, seventh edition, 2010; Table 1). Prognoses were analyzed and compared based on surgical operations.

| Primary tumor (T) | |||

| TX Primary tumor cannot be assessed | |||

| T0 No evidence of primary tumor | |||

| Tis Carcinoma in situ | |||

| T1 Tumor invades lamina propria or muscle layer | |||

| T1a Tumor invades lamina propria | |||

| T1b Tumor invades muscle layer | |||

| T2 Tumor invades muscle layer, no extension beyond the serosa or into the liver | |||

| T3 Tumor perforates the serosa and/or directly invades the liver and/ or one other adjacent organ or structure | |||

| T4 Tumor invades main portal vein or hepatic artery or invade two or more extrahepatic organs or structures | |||

| Regional lymph nodes (N) | |||

| NX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | |||

| N0 No regional lymph node metastases | |||

| N1 Metastases to nodes along the cystic duct, common bile duct, hepatic artery, and/or portal vein | |||

| N2 Metastases to periarotic, pericaval, and/or celiac artery lymph nodes | |||

| Distant metastasis (M) | |||

| M0 No distant metastasis | |||

| M1 Distant metastasis | |||

| Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| Stage I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| Stage II | T2 | N0 | M0 |

| Stage IIIA | T3 | N0 | M0 |

| Stage IIIB | T1-3 | N1 | M0 |

| Stage IVA | T4 | N0-1 | M0 |

| Stage IVB | Any T | N2 | M0 |

| Any T | Any N | M1 | |

A variety of surgical procedures were involved in the treatment of GBC, including simple cholecystectomy, radical cholecystectomy (or extended radical cholecystectomy), and palliative surgery. Simple cholecystectomy is, by definition, resection of the gallbladder fossa. Radical cholecystectomy involves a wedge resection of the gallbladder fossa with 2 cm non-neoplastic liver tissue; resection of a suprapancreatic segment of the extrahepatic bile duct and extended portal lymph node dissection may also be considered based on the patient’s circumstance. Palliative surgery refers to cholecystectomy with biliary drainage.

Data analyses were performed with SPSS 19.0 (IBM. United States). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Logrank test were used for survival rate comparison. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Professor Guangliang Shan’s group from Teaching and Research Section of Peking Union Medical College.

A total of 152 patients were reviewed, including 61 males and 91 females, with a median age of 68 ranging from 29-89 years old. Among them, 36 cases are still alive currently, 97 cases were deceased with a median survival time of 8 mo (ranging from 1 to 67 mo), and the remaining 19 (12.5%) cases were censored. The results of this study showed that the 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates of patients with GBC were 54.40%, 34.70% and 25.75%, respectively.

One hundred and thirty-five of the 152 patients underwent pathological examination, among whom the majority (n = 122) had adenocarcinoma, and the rest had adenosquamous carcinoma (n = 3), squamous carcinoma (n = 2), sarcoma (n = 1), gallbladder adenoma with focal adenocarcinoma (n = 5), or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 2). The other 17 patients who were not suitable for surgery due to late presentation were diagnosed and staged based on clinical data and imaging findings. Among the 135 cases with pathological examination, 26 were well-differentiated carcinoma, 50 moderately differentiated, 42 poorly differentiated, and 17 had no report of tumor differentiation grade. The proportions of patients from each differentiation grade that has been implemented with certain surgical procedures are shown in Table 2.

| Item | Number | Simple cholecystectomy | Radical cholecystectomy | Palliative resection | No surgery |

| Age | |||||

| mean ± SD | 63.75 ± 11.86 | 66.61 ± 11.07 | 62.75 ± 11.38 | 63.53 ± 13.19 | 63.68 ± 12.01 |

| Range | 29-89 | 50-89 | 36-85 | 29-81 | 39-83 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 61 (40.13) | 10 (16.39) | 22 (36.07) | 13 (21.31) | 16 (26.23) |

| Female | 91 (59.87) | 18 (19.78) | 33 (36.26) | 18 (19.78) | 22 (24.18) |

| Differentiation | |||||

| High | 26 (17.11) | 10 (38.46) | 6 (23.08) | 8 (30.77) | 2 (7.69) |

| Median | 50 (32.89) | 9 (18.00) | 26 (52.00) | 7 (14.00) | 8 (16.00) |

| Low | 42 (27.63) | 3 (7.14) | 20 (47.62) | 11 (26.19) | 8 (19.05) |

| No report | 34 (22.37) | 6 (17.65) | 4 (11.76) | 4 (11.76) | 20 (58.82) |

| Total | 152 | 28 (18.42) | 57 (37.50) | 28 (18.42) | 39 (25.66) |

Patients were grouped based on the new 7th edition of TNM staging system, and correlation of prognoses and surgical procedures were analyzed in each group, including 8 cases of stage 0, 10 cases of stage I, 25 cases of stage II, 21 cases of stage IIIA, 21 cases of stage IIIB, 24 cases of stage IVA, 43 cases of stage IVB. Simple cholecystectomy was performed on 28 cases, radical cholecystectomy or expanded gallbladder radical resection on 57 cases, and palliative resection on 28 cases. Thirty-nine cases were not operated (Table 3). Fourteen postoperative complications were documented as fat liquefaction of incision and severe MODS (Table 4).

| TNM stage | Case | Simple cholecystectomy | Radical cholecystectomy | Palliative resection | Inoperable | P value1 |

| 0 + I | 18 (11.84) | 12 (66.67) | 6 (33.33) | 0 | 0 | 0.826 |

| II | 25 (16.45) | 16 (64.00) | 9 (26.00) | 0 | 0 | 0.114 |

| IIIA | 21 (13.82) | 0 | 12 (57.14) | 9 (42.86) | 0 | 0.034 |

| IIIB | 21 (13.82) | 0 | 11 (52.38) | 10 (47.62) | 0 | 0.701 |

| IVA | 24 (15.79) | 0 | 19 (79.17) | 2 (8.33) | 3 (12.50) | 0.6862 |

| IVB | 43 (28.29) | 0 | 0 | 7 (16.28) | 36 (83.72) | 0.001 |

| Total | 152 | 28 (18.54) | 57 (37.50) | 28 (18.42) | 39 (25.66) |

| TNM stage | Surgical procedures | Age(mean ± SD) | P value | Complication | |

| 0-I | Simple cholecystectomy | 61.58 ± 10.587 | 0.662 | 1 | Infection under the skin incision with gallbladder bed bleeding |

| Radical cholecystectomy | 64.17 ± 13.527 | 0 | |||

| II | Simple cholecystectomy | 71.56 ± 9.893 | 0.371 | 0 | |

| Radical cholecystectomy | 68.22 ± 6.220 | 1 | Fat liquefaction of incision | ||

| IIIA | Radical cholecystectomy | 61.67 ± 12.397 | 0.367 | 0 | |

| Palliative resection | 67.00 ± 13.991 | 1 | Biliary fistula | ||

| IIIB | Radical cholecystectomy | 65.82 ± 7.973 | 0.510 | 0 | |

| Palliative resection | 62.20 ± 14.676 | 2 | Biliary fistula, pulmonary embolism | ||

| IVA | Radical cholecystectomy | 67.47 ± 9.553 | 0.066 | 3 | MODS resulting from biliary tract infection (dead), deep vein thrombosis, deterioration of liver function |

| Palliative resection and No surgery | 57.80 ± 11.520 | 1 | Lung infection | ||

| IVB | Palliative resection | 65.57 ± 14.293 | 0.817 | 3 | Abdominal infection, acute pulmonary edema, subphrenic effusion |

| No surgery | 64.39 ± 11.905 | 2 | MODS (dead) |

Due to limited case number, stages 0 and I were combined into one group, 12 of them were operated by simple cholecystectomy and 6 by radical cholecystectomy. No significant differences in survival time were found between the two surgery procedures (χ2 = 0.048, P = 0.826) (Figure 1A). In the stage II group, 16 patients underwent simple cholecystectomy while 9 underwent radical cholecystectomy. Since all the cases have been censored, survival time cannot be calculated. However, by comparing two sets of data, we believed that the prognosis of the radical surgery group may be better than that of the simple cholecystectomy group. The simple cholecystectomy group included 7 dead cases (a survival range of 12-24 mo, with a median survival time of 28 mo) and 3 survivors (survival time was currently 77, 66, and 59 mo), while in the surgery group (9 cases), 6 cases survived (a current survival range of 2-82 mo, with a median survival time of 12.5 mo) (Figure 1B). Among the 42 stage III patients, 23 were operated by extended radical cholecystectomy and the other 19 underwent palliative resection. Survival analysis showed a statistically significant difference between the two operation procedures (P < 0.05, Figure 1C). Among the 21 stage IIIA patients, 12 were operated by extended radical cholecystectomy and the other 9 underwent palliative resection. Survival analysis showed a statistically significant difference between the two operation procedures (P < 0.05, Figure 1D). Different result was observed from the stage IIIB group in which 7 patients were operated by extended radical cholecystectomy and 10 by palliative resection (P > 0.05, Figure 1E). In the stage IVA group, extended radical cholecystectomy did not result in longer survival time than palliative resection and/or non-surgical treatment (P > 0.05, Figure 1F). However, we found significant differences in the stage IVB group in which palliative resection resulted in longer survival time than non-surgical treatment (P < 0.05, Figure 1G).

To determine the most suitable surgical procedure for various stages of GBC is always challenging. Most studies agreed that simple cholecystectomy was sufficient for T0 and T1a (lamina propria invasion) patients[5,10,11]. Different opinions existed for T1b (muscle invasion) GBC treatment. Some studies supported simple cholecystectomy[12], whereas others advocated radical cholecystectomy[8,13]. The American NCCN guideline recommends radical resection to T1b with regional lymph node dissection[14]. However, it was difficult to have a confirmed pre-surgical diagnosis to distinguish T1a and T1b, which explained the reason that a relative high proportion of radical cholecystectomy was performed. Nevertheless, our data provided evidence that simple cholecystectomy should be the first choice for patients at stage I. More aggressive resection did not bring more benefit to patients. Unfortunately, given the rarity of patient falling into this category[15], this observation needs to be verified in larger clinical trials.

Radical cholecystectomy was the major surgical intervention for stage II and more advanced GBC at our hospital, as widely accepted internationally[16,17]. The proportions of patients who underwent radical cholecystectomy for stages II, III, and IVA were 47.6%, 50%, and 79.2%, respectively, much higher than those reported in the United States[18]. Some studies even suggested that for stage II and more advanced GBC, lymph node dissection should include N1 and N2 nodes[13]. Although statistics cannot be calculated for censored cases, by comparing the two sets of data, radical gallbladder resection may be suggested for patients in stage II which may have better prognosis than simple cholecystectomy.

Stage III GBC perforated through the serosa, and (or) involved the liver and (or) other one adjacent organs, or hilar lymph nodes (N1). Even though it was still operable at stage III, substantial morbidity existed from the GBC itself as well as from the operation. A previous study suggested that extended radical surgery can bring a better survival[8]. One study even concluded that extended radical resection is the only chance for patients to survive[15], despite of its high mortality. In the case of stage IIIA, more radical resections were performed and resulted in longer survival time. For stage IIIB patients, however, relatively more palliative resections were performed at our hospital, which were proven to be less beneficial. Our data suggested that, for stage III patients, especially those with stage IIIA disease, radical cholecystectomy or extended radical resection should be pursued.

Stage IV GBC is the most difficult stage for treatment decision, since cancer has invaded the hepatic artery, portal vein, more adjacent organs, and distant lymph nodes or organs. The standard simple cholecystectomy would never be an option for this state. Whether extended radical cholecystectomy or palliative resection should be applied remains controversial. In general extended radical cholecystectomy was more popular in Japan and China[19,20]. Some reports have suggested certain benefits to perform radical resection on patients with stage IV GBC[21,22], while other studies concluded differently[23]. One notion was widely accepted that careful consideration should be taken before applying any surgical treatment due to high morbidity and mortality[24]. In our study, among the 24 stage IVA cases, 19 underwent extended radical cholecystectomy and 5 chose to have palliative or non-surgical treatment. The number for palliative and non-surgical treatment was too limited to have a statistical comparison. Nevertheless, data suggested that extended radical cholecystectomy might not a good choice for patients at this terminal stage. As for stage IVB GBC patients, it is generally considered that palliative treatment would be the most suitable measure[25,26]. Our data suggested that the palliative resection group significantly outlived the non-surgical treatment group.

In summary, based on the new TNM classification system, we concluded that (1) simple cholecystectomy would be the best choice for stages 0 and I GBC patients; (2) stages II and III patients should actively seek for radical cholecystectomy (or extended radical resection surgery); and (3) palliative treatment should be a major method for patients with stage IV GBC, and careful evaluation was necessary before applying any more aggressive surgical procedure.

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is the most common and aggressive malignant disease in the biliary system. Due to the lack of specific signs and symptoms, most of the cases were either diagnosed incidentally or at an advanced stage, which led to poor prognosis. Surgical resection is still the only chance for cure, however, choice of surgery procedure based upon disease stages remains an important topic. Surgical management of GBC that had been documented from different countries or areas of territorial locations demonstrated different results of prognosis.

A variety of surgical procedures were involved in the treatment of GBC, including simple cholecystectomy, radical cholecystectomy (or extended radical cholecystectomy), and palliative surgery. The current research hotspot is to determine the most suitable surgical procedure for various stages of GBC.

The data provided evidence that simple cholecystectomy should be the first choice for patients at stage I. More aggressive resection did not bring more benefit to patients. Radical cholecystectomy or extended radical resection should be pursued for stages II and III GBC patients. Extended radical cholecystectomy might not be a good choice for patients at IVA stage. As for stage IVB GBC patients, our data suggested that the palliative resection group significantly outlived the non-surgical treatment group.

It is necessary to thoroughly evaluate tumor stages for GBC patients by interdisciplinary collaboration among surgeons, oncologists, endoscopy experts before applying any surgical treatment.

Gallbladder cancer is a highly lethal and aggressive disease with a poor prognosis. It is the most common malignant lesion of the biliary tract. Simple cholecystectomy is, by definition, resection of the gallbladder fossa. Radical cholecystectomy involves a wedge resection of the gallbladder fossa with 2 cm non-neoplastic liver tissue; resection of a suprapancreatic segment of the extrahepatic bile duct and extended portal lymph node dissection may also be considered based on the patient’s circumstance. Palliative surgery refers to cholecystectomy with biliary drainage.

This is a very interesting study about the impact of surgical procedures on prognosis of gallbladder cancer patients. In this study, the authors performed a review of 152 patients with primary gallbladder carcinoma. This study showed that simple cholecystectomy would be the best choice for stages 0 and I GBC patients; stages II and III patients should actively seek for radical cholecystectomy (or extended radical resection surgery); and palliative treatment should be a major method for patients with stage IV GBC, and careful evaluation was necessary before applying any more aggressive surgical procedure.

Institutional review board: The study was reviewed and approved by the Peking Union Medical College Hospital Institutional Review Board.

P- Reviewer: Hardy T, Liu XF, Zhang ZM S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Reid KM, Ramos-De la Medina A, Donohue JH. Diagnosis and surgical management of gallbladder cancer: a review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:671-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yuan Y, Yang ZL, Zou Q, Cao LF, Tan XG, Jiang S, Miao XY. Clinicopathological significance of DNA fragmentation factor 45 and thyroid transcription factor 1 expression in benign and malignant lesions of the gallbladder. Pol J Pathol. 2013;64:44-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yang XW, Yang J, Li L, Man XB, Zhang BH, Shen F, Wu MC. Analysis of the relationships between clinicopathologic factors and survival in gallbladder cancer following surgical resection with curative intent. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tamura S, Sugawara Y. Hepatobiliary surgery: the past, present, and future learned from Professor Henri Bismuth. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2014;3:55-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | D’Angelica M, Dalal KM, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR. Analysis of the extent of resection for adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:806-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hueman MT, Vollmer CM, Pawlik TM. Evolving treatment strategies for gallbladder cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2101-2115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Reddy SK, Marroquin CE, Kuo PC, Pappas TN, Clary BM. Extended hepatic resection for gallbladder cancer. Am J Surg. 2007;194:355-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Boutros C, Gary M, Baldwin K, Somasundar P. Gallbladder cancer: past, present and an uncertain future. Surg Oncol. 2012;21:e183-e191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Oh TG, Chung MJ, Bang S, Park SW, Chung JB, Song SY, Choi GH, Kim KS, Lee WJ, Park JY. Comparison of the sixth and seventh editions of the AJCC TNM classification for gallbladder cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:925-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shirai Y, Yoshida K, Tsukada K, Muto T, Watanabe H. Radical surgery for gallbladder carcinoma. Long-term results. Ann Surg. 1992;216:565-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wagholikar GD, Behari A, Krishnani N, Kumar A, Sikora SS, Saxena R, Kapoor VK. Early gallbladder cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194:137-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sun CD, Zhang BY, Wu LQ, Lee WJ. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for treatment of unexpected early-stage gallbladder cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91:253-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sikora SS, Singh RK. Surgical strategies in patients with gallbladder cancer: nihilism to optimism. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:670-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Benson AB, Bekaii-Saab T, Ben-Josef E, Blumgart L, Clary BM, Curley SA, Davila R, Earle CC, Ensminger WD, Gibbs JF. Hepatobiliary cancers. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006;4:728-750. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Kiran RP, Pokala N, Dudrick SJ. Incidence pattern and survival for gallbladder cancer over three decades--an analysis of 10301 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:827-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shirai Y, Yoshida K, Tsukada K, Muto T. Inapparent carcinoma of the gallbladder. An appraisal of a radical second operation after simple cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 1992;215:326-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | D’Hondt M, Lapointe R, Benamira Z, Pottel H, Plasse M, Letourneau R, Roy A, Dagenais M, Vandenbroucke-Menu F. Carcinoma of the gallbladder: patterns of presentation, prognostic factors and survival rate. An 11-year single centre experience. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:548-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jensen EH, Abraham A, Habermann EB, Al-Refaie WB, Vickers SM, Virnig BA, Tuttle TM. A critical analysis of the surgical management of early-stage gallbladder cancer in the United States. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:722-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Meng H, Wang X, Fong Y, Wang ZH, Wang Y, Zhang ZT. Outcomes of radical surgery for gallbladder cancer patients with lymphatic metastases. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:992-998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shirai Y, Sakata J, Wakai T, Ohashi T, Hatakeyama K. “Extended” radical cholecystectomy for gallbladder cancer: long-term outcomes, indications and limitations. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4736-4743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fong Y, Jarnagin W, Blumgart LH. Gallbladder cancer: comparison of patients presenting initially for definitive operation with those presenting after prior noncurative intervention. Ann Surg. 2000;232:557-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Balachandran P, Agarwal S, Krishnani N, Pandey CM, Kumar A, Sikora SS, Saxena R, Kapoor VK. Predictors of long-term survival in patients with gallbladder cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:848-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sakamoto Y, Nara S, Kishi Y, Esaki M, Shimada K, Kokudo N, Kosuge T. Is extended hemihepatectomy plus pancreaticoduodenectomy justified for advanced bile duct cancer and gallbladder cancer? Surgery. 2013;153:794-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Marino D, Colombi F, Ribero D, Aglietta M, Leone F. Targeted agents: how can we improve the outcome in biliary tract cancer? Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2013;2:31-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Horiguchi A, Miyakawa S, Ishihara S, Miyazaki M, Ohtsuka M, Shimizu H, Sano K, Miura F, Ohta T, Kayahara M. Gallbladder bed resection or hepatectomy of segments 4a and 5 for pT2 gallbladder carcinoma: analysis of Japanese registration cases by the study group for biliary surgery of the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:518-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wang C, Xu Y, Lu X. Should preoperative biliary drainage be routinely performed for obstructive jaundice with resectable tumor? Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2013;2:266-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |