Published online Apr 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4592

Peer-review started: November 10, 2014

First decision: November 26, 2014

Revised: January 7, 2014

Accepted: January 30, 2015

Article in press: January 30, 2015

Published online: April 21, 2015

Processing time: 162 Days and 14.9 Hours

AIM: To evaluate whether individuals with gastric cancer (GC) are diagnosed earlier if they have first-degree relatives with GC.

METHODS: A total of 4282 patients diagnosed with GC at National Cancer Center Hospital from 2002 to 2012 were enrolled in this retrospective study. We classified the patients according to presence or absence of first-degree family history of GC and compared age at diagnosis and clinicopathologic characteristics. In addition, we further classified patients according to specific family member with GC (father, mother, sibling, or offspring) and compared age at GC diagnosis among these patient groups. Baseline characteristics were obtained from a prospectively collected database. Information about the family member’s age at GC diagnosis was obtained by questionnaire.

RESULTS: A total of 924 patients (21.6%) had a first-degree family history of GC. The mean age at GC diagnosis in patients having paternal history of GC was 54.4 ± 10.4 years and was significantly younger than in those without a first-degree family history (58.1 ± 12.0 years, P < 0.001). However, this finding was not observed in patients who had an affected mother (57.2 ± 10.0 years) or sibling (62.2 ± 9.8 years). Among patients with family member having early-onset GC (< 50 years old), mean age at diagnosis was 47.7 ± 10.3 years for those with an affected father, 48.6 ± 10.4 years for those with an affected mother, and 57.4 ± 11.5 years for those with an affected sibling. Thus, patients with a parent diagnosed before 50 years of age developed GC 10.4 or 9.5 years earlier than individuals without a family history of GC (both P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION: Early-onset GC before age of 50 was associated with parental history of early-onset of GC. Individual having such family history need to start screening earlier.

Core tip: A family history of cancer is associated with earlier age of onset of several cancers, but not clear in gastric cancer (GC). We found that individuals with a paternal history of GC tended to diagnosis at younger age than those patients without family history, also individuals with a parent diagnosed before 50 years of age developed GC about 10 years earlier than those patients without family history. The finding that patients with a parental history of GC, especially those who had parents with early-onset GC, diagnosed at younger age supports the need for early screening in these individuals.

- Citation: Kwak HW, Choi IJ, Kim CG, Lee JY, Cho SJ, Eom BW, Yoon HM, Joo J, Ryu KW, Kim YW. Individual having a parent with early-onset gastric cancer may need screening at younger age. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(15): 4592-4598

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i15/4592.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4592

A family history of cancer increases the risk of several cancers[1-3]. In addition, the earlier a family member diagnosed to have a colorectal cancer, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, prostate, and thyroid cancer, the higher the risk of developing cancer for others in the family. A family history of cancer is also associated with earlier age of onset for colorectal cancer, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, and thyroid cancer[4-7]. Taken together, these studies suggest that individuals with a family history of colorectal, breast, or ovarian cancer, especially with earlier age of onset, should undergo screening earlier than the normal population[2,6,8-10] and may require surgery[11] or chemoprevention[12] to reduce their cancer risk.

Family history is also an important risk factor for gastric cancer (GC). Studies have shown that individuals with a family history of GC have a higher risk of developing GC than controls (OR = 1.3-8.5)[13-19], and early diagnosis is associated with a higher GC risk for other family members[20]. However, the relationship between family history and age at GC onset/diagnosis is unclear. Therefore, in this study we compared age at diagnosis in patients with or without a first-degree family history of GC to determine whether patients with a family history of GC are diagnosed earlier.

For this retrospective study we identified 5413 patients with GC at the National Cancer Center Hospital in South Korea using a prospectively collected database. For all patients the diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma was confirmed by histology from October 2002 to December 2012.

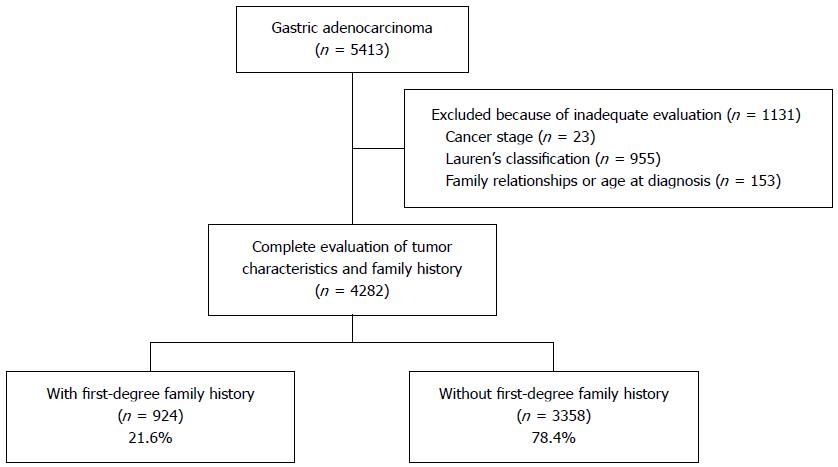

We excluded 1131 patients who were inadequately evaluated for cancer stage, Lauren’s classification, family history, or age at diagnosis. Our final study population consisted of 4282 patients (Figure 1). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center, South Korea (NCCNCS-13-820).

We classified the 4282 patients according to presence or absence of first-degree family history of GC and compared age at diagnosis and clinicopathologic characteristics. In addition, we further classified patients according to specific family member with GC (father, mother, sibling, or offspring) and compared age at GC diagnosis among these patient groups.

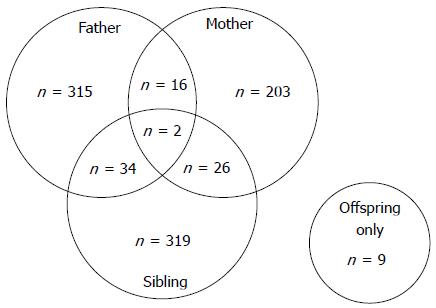

Because we wanted to evaluate the influence of paternal and maternal history separately, we excluded patients with a family history of both parents developing GC (n = 18). We defined patients with a paternal history (n = 349, 37.8%) as those whose father only was affected (n = 315) or both father and sibling (but not mother) were affected (n = 34) (Figure 2). Similarly, we defined patients with a maternal history (n = 229, 24.8%) as those whose mother only was affected (n = 203) or both mother and sibling (but not father) were affected (n = 26). We defined patients with a sibling history as those whose sibling (but not parents) was affected (n = 319, 34.5%). Of the 16 patients who had offspring with GC, those who also had other affected family members were classified into the paternal, maternal, or sibling history group. The remaining nine patients had offspring only with GC; because of its small size, this subgroup was excluded from analysis.

Age at diagnosis and clinicopathologic characteristics were compared between patients with or without a first-degree family history. Among the clinicopathologic variables, current Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection was defined by positive histology or rapid urease test (RUT) results, whereas past H. pylori infection was defined by positive serology but negative histology and RUT results. Negative H. pylori infection was defined by negative results for all three tests (histology, RUT, and serology).

Cancer was staged according to the TNM classification on the basis of final pathology, abdominal computed tomography, or endoscopic ultrasonography findings. TNM classification was performed according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th cancer staging manual[21].

χ2 tests were performed to compare categorical variables and evaluate the relationship between H. pylori infection status and cancer stage. Independent t-tests were performed to assess significant differences between the means of two unrelated groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare the means of three unrelated groups. A post-hoc test was done using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test. Analyses were performed with the STATA version 10.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, United States). P < 0.05 was considered significant. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Jungnam Joo from Cancer Biostatistics Branch, Nation Cancer Center, South Korea.

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of patient inclusion and classification. Age at diagnosis and clinicopathologic characteristics of both groups are summarized in Table 1. Patients with a family history had smaller lesions and more intestinal-type cancers than the patients without a family history. However, overall mean age, proportion of male patients, H. pylori infection status, and cancer stage did not differ significantly between groups.

| Total (4282) | With first-degree family history | Without first-degree family history | ||

| n = 924 (21.6%) | n = 3358 (78.4%) | P value | ||

| Age at diagnosis, yr (mean ± SD) | 58.0 ± 11.8 | 58.0 ± 10.7 | 58.1 ± 12.0 | 0.8971 |

| Male | 2886 (67.4) | 620 (67.1) | 2266 (67.5) | 0.8271 |

| Female | 1396 (32.6) | 304 (32.9) | 1092 (32.5) | |

| Tumor diameter (mean ± SD) | 4.0 ± 2.7 | 3.8 ± 2.6 | 4.2 ± 2.8 | 0.0041 |

| Lauren’s classification | < 0.0012 | |||

| Intestinal | 2251 (52.6) | 544 (58.9) | 1707 (50.8) | |

| Diffuse | 1642 (38.3) | 300 (32.5) | 1342 (40.0) | |

| Mixed | 389 (9.1) | 80 (8.6) | 309 (9.2) | |

| H. pylori infection status | 0.1742 | |||

| Current | 2851 (66.6) | 612 (66.2) | 2239 (66.7) | |

| Past | 622 (14.5) | 114 (12.3) | 508 (15.1) | |

| Negative | 536 (12.5) | 119 (12.9) | 417 (12.4) | |

| Not available | 273 (6.4) | 79 (8.5) | 194 (5.8) | |

| GC stage | 0.0812 | |||

| Stage 1 | 3009 (70.3) | 679 (73.5) | 2330 (69.4) | |

| Stage 2 | 568 (13.3) | 114 (12.3) | 454 (13.5) | |

| Stage 3 | 476 (11.1) | 92 (10.0) | 384 (11.4) | |

| Stage 4 | 229 (5.3) | 39 (4.2) | 190 (5.7) |

Among patients with a first-degree family history of GC, age at diagnosis was evaluated according to the affected family member (Table 2). The mean age at diagnosis was 54.4 ± 10.4 for patients with a paternal history, 57.2 ± 10.0 years for patients with a maternal history, and 62.2 ± 9.8 years for patients with a sibling history (P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA), and each pair of means differed significantly (P < 0.05, Tukey’s HSD test). Patients with a paternal history were younger at the time of diagnosis than those without a family history. However, age at diagnosis for patients with a maternal history did not differ significantly from that of those without a family history, and patients with a sibling history were older at diagnosis than those without a family history.

| Father | Mother | Sibling | P value | |||

| n = 349 (37.8%) | n = 229 (24.8%) | n = 319 (34.5%) | Father vs mother | Father vs sibling | Mother vs sibling | |

| Age at diagnosis, yr (mean ± SD) | 54.4 ± 10.4 | 57.2 ± 10.0 | 62.2 ± 9.8 | 0.0021 | < 0.0011 | < 0.0011 |

| Male | 252 (72.2) | 137 (59.8) | 213 (66.8) | 0.0022 | 0.1272 | 0.0952 |

| Female | 97 (27.8) | 92 (40.2) | 106 (33.2) | |||

| Tumor diameter (mean ± SD) | 3.9 ± 2.8 | 3.9 ± 2.4 | 3.8 ± 2.4 | 0.9881 | 0.6611 | 0.6611 |

| Lauren’s classification | 0.7642 | 0.0032 | 0.0212 | |||

| Intestinal | 191 (54.7) | 132 (57.6) | 205 (64.3) | |||

| Diffuse | 130 (37.3) | 81 (35.4) | 80 (25.1) | |||

| Mixed | 28 (8.0) | 16 (7.0) | 34 (10.7) | |||

| H. pylori infection status | 0.5302 | 0.5192 | 0.8272 | |||

| Current | 241 (69.1) | 150 (65.5) | 206 (64.6) | |||

| Past | 43 (12.3) | 25 (10.9) | 42 (13.2) | |||

| Negative | 37 (10.6) | 32 (14.0) | 45 (14.1) | |||

| Not available | 28 (8.0) | 22 (9.6) | 26 (8.2) | |||

| Gastric cancer stage | 0.1932 | 0.7462 | 0.1862 | |||

| Stage 1 | 254 (72.8) | 166 (72.5) | 235 (73.7) | |||

| Stage 2 | 41 (11.7) | 28 (12.2) | 43 (13.5) | |||

| Stage 3 | 35 (10.0) | 30 (13.1) | 27 (8.5) | |||

| Stage 4 | 19 (5.4) | 5 (2.2) | 14 (4.4) | |||

Among patients with a first-degree family history of GC, clinicopathologic characteristics were evaluated according to the affected family member (Table 2). The proportion of males was higher among patients who had a paternal history compared with those who had a maternal history. Intestinal-type GC was more common among patients with a sibling history compared with those who had a paternal history or maternal history. However, mean tumor size, H. pylori infection status, and cancer stage did not differ significantly among groups.

Age at diagnosis of patients who had a first-degree family member diagnosed with early-onset GC (diagnosed before the age of 50) was compared with the age at diagnosis of patients without a first-degree family history (58.1 ± 12.0) (Table 3). We found that the age at diagnosis of patients who had a father with early-onset GC or mother with early-onset GC was younger than that of patients without a family history (both P < 0.001). However, the age at diagnosis of patients who had a sibling with early-onset GC was not significantly different from that of patients without a family history.

Among patients with a first-degree family history of GC, age at diagnosis was evaluated according to the affected family member’s age at diagnosis (Table 3). Patients who had a family member with early-onset GC were also younger on average at the time of diagnosis compared with patients whose family member had later-onset GC (P < 0.001). Similar results were obtained when evaluating age at diagnosis according to GC diagnosis (< 50 years vs > 50 years) of the father, mother, or sibling (all P < 0.001).

We also found that patients whose fathers had later-onset GC were younger at the time of diagnosis than patients without a first-degree family history. However, age at diagnosis of patients whose mothers had later-onset GC did not differ significantly from that of patients without a first-degree family history, and patients whose siblings had later onset GC were older at the time of diagnosis.

We then classified patients according to age at diagnosis (10-year intervals) and compared age at diagnosis between patients who had a first-degree family member with early-onset GC and patients without a first-degree family history of GC (Table 4). The proportion of patients who were younger than 50 years at the time of diagnosis was higher among those who had a father or mother with early-onset GC compared with those without a family history. However, the age at diagnosis of patients who had a sibling with early-onset GC was similar to that of patients without a family history.

| Patient’s age at diagnosis, (yr) | Patients with family member diagnosed before 50 yr of age | Patients without a first-degree family history | ||

| Father | Mother | Sibling | ||

| n = 39 | n = 24 | n = 100 | n = 3358 | |

| < 40 | 10 (25.6) | 5 (20.8) | 7 (7.0) | 239 (7.1) |

| 40-49 | 13 (33.3) | 8 (33.3) | 19 (19.0) | 610 (18.2) |

| 50-59 | 10 (25.6) | 6 (25.0) | 31 (31.0) | 854 (25.4) |

| ≥ 60 | 6 (15.4) | 5 (20.8) | 43 (43.0) | 1655 (49.3) |

| P-value1 | < 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.573 | |

In this study, we evaluated whether patients with GC who had a first-degree family history of the disease were younger at the time of diagnosis. We found that patients with a paternal history of GC were 3.7 years younger on average at diagnosis than patients without a family history. Patients whose fathers had early-onset GC (diagnosed before 50 years of age) were 10.4 years younger at diagnosis than patients without a family history, and those whose mothers had early-onset GC were 9.5 years younger. We also found that patients whose fathers had later-onset GC were 2.8 younger at diagnosis than patients without a family history, although age at diagnosis of patients with mothers or siblings with later-onset GC was similar to that of patients without a family history.

There are several hypotheses for the relationship between parent history of GC and age at diagnosis. The sharing of environmental risk factors is one possible explanation. The family is the core unit of H. pylori transmission, and H. pylori is more prevalent among family members of patients with GC. In addition, similar dietary patterns such as high sodium consumption may explain the increased risk of GC in individuals with a family history of the disease[22,23]. Although these factors could increase the risk of GC among the family members, their relationship with early onset of the disease remains unclear. In addition, genes that control the inflammatory response may also contribute to gastric cancer development. In particular, polymorphisms in genes encoding the cytokines interleukin-1β, interleukin-10, and tumor necrosis factor-α have been reported to increase the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma in family members of patients with GC, possibly by inducing hypochlorhydria and atrophic gastritis in response to H. pylori infection[24,25].

In diffuse type gastric cancer, 1%-3% of cases with familial clustering meet the criteria for hereditary diffuse gastric cancer caused by CDH1 germline mutations, which appears to increase the risk of early-onset GC[26-28]. We were unable to evaluate tumor histology of the family members because of the retrospective nature of our study; however, hereditary diffuse gastric cancer appears to be uncommon in South Korea[29]. In our study only 13 patients (1.4%) of those with a family history of GC had three or more affected family members.

In our study, patients with a paternal history of GC developed the disease earlier than patients with other affected first-degree family members. In a study of colorectal cancer, Lindor et al[30] explained that preferential inactivation of the maternal X chromosome could unmask the X-linked allele inherited from the father that predisposes the daughter to develop cancer at a younger age. Alternatively, individuals with a family history of cancer may be younger at the time of diagnosis because they are likely to undergo screening earlier than the general population. For example, Claus et al[10] reported that women with a family history of breast cancer may be offered more intensive surveillance. Kang et al[31] compared GC screening rates, smoking rates, and dietary patterns (e.g., sodium, vitamin, and fiber consumption) between individuals with or without a family history of GC and found that although lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking, diet) did not differ between two groups, those with a family history of GC may undergo screening at a younger age.

In older patients, intestinal-type GC is more common than diffuse GC[32,33]. In addition, patients with a family history of GC were more likely to have intestinal-type GC than patients without a family history[34]. This relationship between histologic type and age at diagnosis is consistent with our finding that patients with a sibling history of GC, who were older at the time of diagnosis than patients without a first-degree family history, were more likely to develop intestinal-type GC than diffuse or mixed type GCs (Table 2). Alternatively, patients with a sibling history may develop intestinal-type GC because of lifestyle factors such as H. pylori infection or diet.

Studies of colorectal cancer[2,35], breast cancer[10,35], prostate cancer[35], and lung cancer[35], have found that these cancers develop at a younger age in the offspring of patients with early-onset cancer. These findings were supported by Hemminki et al[1], who also reported that age at diagnosis of colon, rectal, uterine, or ovarian cancers in a parent was associated with age at cancer diagnosis in their offspring. Our study also showed that patients who had a parent with early-onset GC were younger at the time of diagnosis than patients without a first-degree family history. In fact, diagnosis before the age of 40 occurred in more than 20% of patients with a parental history of early-onset GC but in only 7.1% of patients without a family history of GC (Table 4). Therefore, we recommend that patients who have a parent with early-onset GC begin surveillance for GC before the age of 40.

Our study has several limitations. First, we obtained information about the age at diagnosis of first-degree family members using a questionnaire, without direct confirmation. Although these answers rely on the patient’s memory, family relationships in South Korea are typically close, and age at the time of cancer diagnosis in a family member was usually clearly remembered. Second, we didn’t evaluate genetic factors that could be responsible for characteristics of GC.

The finding that patients with a parent history of GC, especially those who had parents with early-onset GC diagnosed before age of 50, were younger at the time of diagnosis supports the need for earlier screening in these individuals, beginning preferably before the age of 40.

A family history of cancer is associated with earlier age of onset for several cancers, but the association is not clear in gastric cancer (GC).

This is the first study to evaluate whether individuals with GC are diagnosed earlier if they have first-degree relatives with GC.

The authors classified patients according to presence or absence of first-degree family history of GC and compared age at diagnosis. In addition, we classified patients according to specific family member with GC (father, mother, sibling, or offspring) and compared age at GC diagnosis among these patient groups.

The finding supports the need for earlier GC screening before the age of 40 in individuals with a parent history of GC, especially those who had a parent with early-onset GC diagnosed before age of 50.

The authors defined patients with a first-degree family history of GC as those with specific family member with GC (father, mother, sibling, or offspring). The authors also defined patients having parents with early-onset GC as those whose father or mother was affected before age of 50.

This study compared age at diagnosis in patients with or without a first-degree family history of GC. The mean age at GC diagnosis in patients having paternal history of GC was significantly younger than in those without a first-degree family history (54.4 vs 58.1), and patients with a parent diagnosed before 50 years of age developed GC about 10 years earlier than individuals without a family history of GC.

P- Reviewer: Decsi T, Franzen T, Ghiorzo P S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Hemminki K, Vaittinen P, Kyyrönen P. Age-specific familial risks in common cancers of the offspring. Int J Cancer. 1998;78:172-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fuchs CS, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Speizer FE, Willett WC. A prospective study of family history and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1669-1674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 510] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Slattery ML, Kerber RA. A comprehensive evaluation of family history and breast cancer risk. The Utah Population Database. JAMA. 1993;270:1563-1568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fallah M, Sundquist K, Hemminki K. Risk of thyroid cancer in relatives of patients with medullary thyroid carcinoma by age at diagnosis. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20:717-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nichols KE, Malkin D, Garber JE, Fraumeni JF, Li FP. Germ-line p53 mutations predispose to a wide spectrum of early-onset cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:83-87. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Dershaw DD. Mammographic screening of the high-risk woman. Am J Surg. 2000;180:288-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Brandt A, Bermejo JL, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. Age at diagnosis and age at death in familial prostate cancer. Oncologist. 2009;14:1209-1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Familial breast cancer: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 52 epidemiological studies including 58,209 women with breast cancer and 101,986 women without the disease. Lancet. 2001;358:1389-1399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 751] [Cited by in RCA: 757] [Article Influence: 31.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dunlop MG. Guidance on large bowel surveillance for people with two first degree relatives with colorectal cancer or one first degree relative diagnosed with colorectal cancer under 45 years. Gut. 2002;51 Suppl 5:V17-V20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Claus EB, Risch NJ, Thompson WD. Age at onset as an indicator of familial risk of breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131:961-972. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Piver MS. Prophylactic Oophorectomy: Reducing the U.S. Death Rate from Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. A Continuing Debate. Oncologist. 1996;1:326-330. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Nayfield SG, Karp JE, Ford LG, Dorr FA, Kramer BS. Potential role of tamoxifen in prevention of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:1450-1459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | La Vecchia C, Negri E, Franceschi S, Gentile A. Family history and the risk of stomach and colorectal cancer. Cancer. 1992;70:50-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hansen S, Vollset SE, Derakhshan MH, Fyfe V, Melby KK, Aase S, Jellum E, McColl KE. Two distinct aetiologies of cardia cancer; evidence from premorbid serological markers of gastric atrophy and Helicobacter pylori status. Gut. 2007;56:918-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yatsuya H, Toyoshima H, Mizoue T, Kondo T, Tamakoshi K, Hori Y, Tokui N, Hoshiyama Y, Kikuchi S, Sakata K. Family history and the risk of stomach cancer death in Japan: differences by age and gender. Int J Cancer. 2002;97:688-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Palli D, Galli M, Caporaso NE, Cipriani F, Decarli A, Saieva C, Fraumeni JF, Buiatti E. Family history and risk of stomach cancer in Italy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3:15-18. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Zanghieri G, Di Gregorio C, Sacchetti C, Fante R, Sassatelli R, Cannizzo G, Carriero A, Ponz de Leon M. Familial occurrence of gastric cancer in the 2-year experience of a population-based registry. Cancer. 1990;66:2047-2051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bakir T, Can G, Erkul S, Siviloglu C. Stomach cancer history in the siblings of patients with gastric carcinoma. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2000;9:401-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yaghoobi M, Bijarchi R, Narod SA. Family history and the risk of gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:237-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shin CM, Kim N, Yang HJ, Cho SI, Lee HS, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Stomach cancer risk in gastric cancer relatives: interaction between Helicobacter pylori infection and family history of gastric cancer for the risk of stomach cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:e34-e39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. (Eds.). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th ed. New York: Springer 2010; . |

| 22. | Tsugane S. Salt, salted food intake, and risk of gastric cancer: epidemiologic evidence. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lee JK, Park BJ, Yoo KY, Ahn YO. Dietary factors and stomach cancer: a case-control study in Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24:33-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rad R, Dossumbekova A, Neu B, Lang R, Bauer S, Saur D, Gerhard M, Prinz C. Cytokine gene polymorphisms influence mucosal cytokine expression, gastric inflammation, and host specific colonisation during Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 2004;53:1082-1089. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Shanks AM, El-Omar EM. Helicobacter pylori infection, host genetics and gastric cancer. J Dig Dis. 2009;10:157-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chen Y, Kingham K, Ford JM, Rosing J, Van Dam J, Jeffrey RB, Longacre TA, Chun N, Kurian A, Norton JA. A prospective study of total gastrectomy for CDH1-positive hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2594-2598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Guilford P, Hopkins J, Harraway J, McLeod M, McLeod N, Harawira P, Taite H, Scoular R, Miller A, Reeve AE. E-cadherin germline mutations in familial gastric cancer. Nature. 1998;392:402-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1135] [Cited by in RCA: 1140] [Article Influence: 42.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Huntsman DG, Carneiro F, Lewis FR, MacLeod PM, Hayashi A, Monaghan KG, Maung R, Seruca R, Jackson CE, Caldas C. Early gastric cancer in young, asymptomatic carriers of germ-line E-cadherin mutations. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1904-1909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Guilford P, Humar B, Blair V. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: translation of CDH1 germline mutations into clinical practice. Gastric Cancer. 2010;13:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lindor NM, Rabe KG, Petersen GM, Chen H, Bapat B, Hopper J, Young J, Jenkins M, Potter J, Newcomb P. Parent of origin effects on age at colorectal cancer diagnosis. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:361-366. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Kang JM, Shin DW, Kwon YM, Park SM, Park MS, Park JH, Son KY, Cho BL. Stomach cancer screening and preventive behaviors in relatives of gastric cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3518-3525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Correa P. Helicobacter pylori and gastric carcinogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19 Suppl 1:S37-S43. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Zheng H, Takahashi H, Murai Y, Cui Z, Nomoto K, Miwa S, Tsuneyama K, Takano Y. Pathobiological characteristics of intestinal and diffuse-type gastric carcinoma in Japan: an immunostaining study on the tissue microarray. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:273-277. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Han MA, Oh MG, Choi IJ, Park SR, Ryu KW, Nam BH, Cho SJ, Kim CG, Lee JH, Kim YW. Association of family history with cancer recurrence and survival in patients with gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:701-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Kharazmi E, Fallah M, Sundquist K, Hemminki K. Familial risk of early and late onset cancer: nationwide prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e8076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |