Published online Mar 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i12.3750

Peer-review started: October 9, 2014

First decision: October 29, 2014

Revised: November 15, 2014

Accepted: December 14, 2014

Article in press: December 16, 2014

Published online: March 28, 2015

Processing time: 172 Days and 15.7 Hours

We report a rare case of cytomegalovirus (CMV) colitis followed by severe ischemic colitis in a non-immunocompromised patient. An 86-year-old woman was admitted after experiencing episodes of vomiting and diarrhea. The next day, hematochezia was detected without abdominal pain. The initial diagnosis of ischemic colitis was based on colonoscopy and histological findings. The follow-up colonoscopy revealed a prolonged colitis. Immunohistochemical staining detected CMV-positive cells following conservative therapy. Intravenous ganciclovir therapy led to successful healing of ulcers and disappearance of CMV-positive cells. The prevalence of CMV infection is common in adults. CMV colitis is relatively common in immunocompromised patients; however, it is rare in immunocompetent patients. In our case, CMV infection was allowed to be established due to the disruption of the colonic mucosa by the prior severe ischemic colitis. Our experience suggests that biopsies may be necessary to detect CMV and the prompt management of CMV colitis should be instituted when intractable ischemic colitis is observed.

Core tip: Cytomegalovirus colitis is common in immunocompromised patients but rare in immunocompetent patients. In cases where ischemic colitis is prolonged, it is important to consider cytomegalovirus colitis. This case report not only represents the colonoscopy and pathological findings in immunocompetent patients, but also applies the method of diagnosing and treating immunocompetent patients.

- Citation: Hasegawa T, Aomatsu K, Nakamura M, Aomatsu N, Aomatsu K. Cytomegalovirus colitis followed by ischemic colitis in a non-immunocompromised adult: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(12): 3750-3754

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i12/3750.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i12.3750

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a well-recognized pathogen, with 40%-100% of the general population showing prior exposure as per serology[1]. However, most infected adults show no symptoms or occasionally show self-limiting infectious mononucleosis[2]. Gastrointestinal CMV disease usually occurs in immunocompromised patients[3]. CMV colitis is rarely reported in non-immunocompromised patients[4]. Herein, we report a rare case of CMV colitis in an immunocompetent patient followed by ischemic colitis and successfully managed by antiviral therapy.

An 86-year-old woman was admitted following one day episodes of vomiting (three times) and diarrhea (three times). The patient denied any recent travel or changes in medication usage, including antibiotics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The patient had a history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension but no history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), renal failure, valvular disease or coronary artery disease. General examination revealed a malnourished woman with a body mass index of 19.1 kg/m2. Her vitals included a body temperature of 36.5 °C, a heart rate of 81 bpm and blood pressure of 82/49 mmHg. Other findings were unremarkable, including a soft abdomen and normal active bowel sounds.

Laboratory results for white blood cells, hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelets, serum creatinine, total protein, albumin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase were within their normal range. C-reactive protein, lactate dehydrogenase, creatinine phosphokinase, serum creatinine (Cre) and fasting blood sugar were slightly elevated at 0.45 mg/dL, 346 U/L, 241 U/L, 0.90 mg/dL and 190 mg/dL, respectively. The prothrombin time was within the normal range, while the activated partial thromboplastin time was short at 20.5 s. Stool culture at the first visit was not performed.

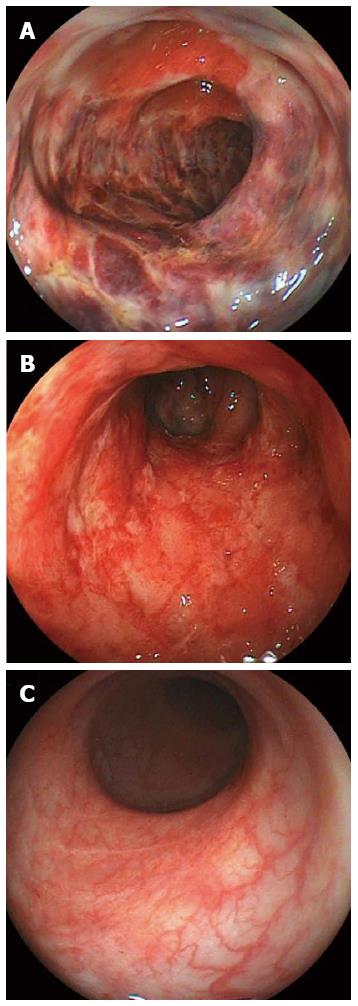

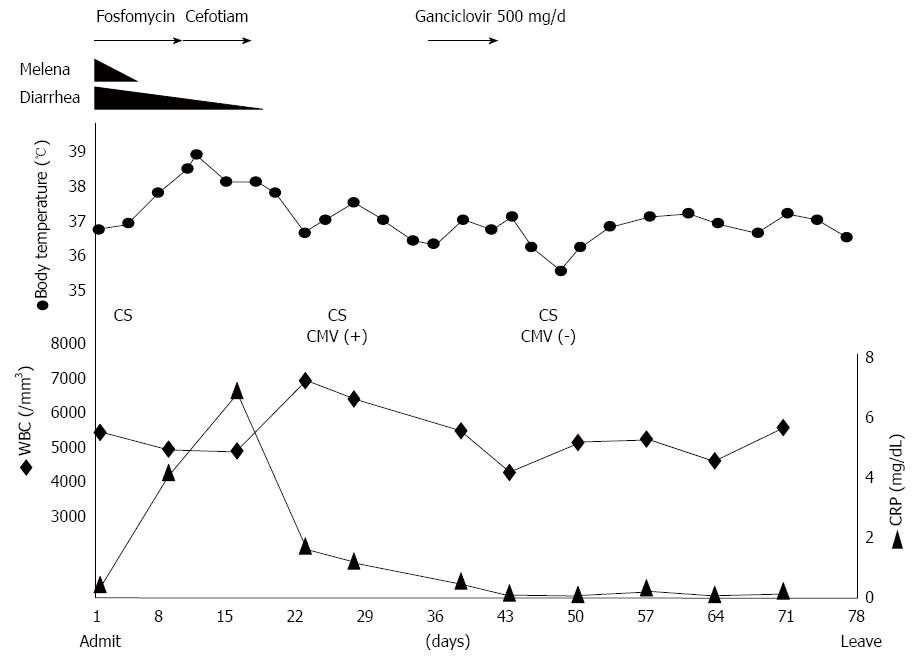

After admission, the patient had a broad-spectrum antibiotic via instillation administered. The next day, diarrhea and vomiting subsided. However, hematochezia was detected without abdominal pain the next day. On day 4, colonoscopy revealed acute, inflamed and friable mucosal changes as well as ulcers spread widely and annularly from the transverse colon to sigmoid colon (Figure 1A). Biopsy specimens taken from the ulcers showed acute exudative colitis compatible with ischemic colitis. After administration of the antibiotic fosfomycin calcium hydrate (2 g/d), a high fever and an elevated white blood cell count were detected on day 11. Consequently, the treatment was changed to 2 g/d of cefotiam hydrochloride. A test for Clostridium difficile toxin in the stool was negative.

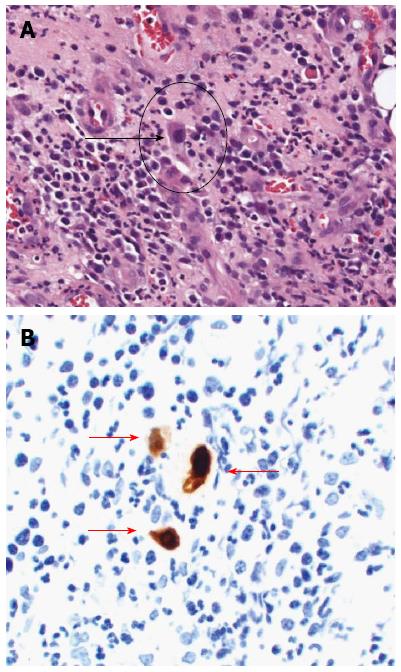

Follow-up colonoscopy on day 25 demonstrated stenosis at the splenic flexure, with a shallow and circumferential ulcer from the descending colon to sigmoid colon remaining (Figure 1B). The stenosis segment, estimated with a contrast medium, appeared short and incomplete. Serum CMV IgG and IgM were seropositive and seronegative, respectively. CMV pp65 antigen was negative. A quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay to detect CMV was not performed. Histopathological evaluation of the biopsy specimens from the colonic mucosa revealed granulation tissue with dilatation of blood capillaries. Enlarged cells with viral inclusions were observed in the biopsy specimens (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemical findings with an anti-CMV antibody showed positively stained cells (Figure 2B). After diagnosis of CMV colitis, the patient was treated with intravenous ganciclovir at 500 mg/d for seven days. A follow-up colonoscopy on day 46 showed disappearance of the colonic ulcers (Figure 1C) and stenosis persisting in the descending colon. A biopsy demonstrated disappearance of the CMV inclusion bodies and the CMV-positive cells. Figure 3 shows the clinical course of the case. The follow-up colonoscopy at five months showed normal mucosa, stenosis in the descending colon and the presence of inflammatory polyps. The patient is carefully monitored once a month, has no trouble evacuating the bowels and remains asymptomatic in November 2014.

CMV is a double-stranded DNA virus belonging to the herpes virus family. CMV infections are common worldwide due to excretion of CMV in bodily fluids, including saliva, respiratory secretions, urine, blood, breast milk and semen, and is transmitted by close personal contact. The prevalence of CMV infections in the general adult population is approximately 40%-100%[1]. In normal hosts, primary infection is usually asymptomatic but can sometimes result in a syndrome similar to infectious mononucleosis, accompanied by symptoms such as fever, myalgia, cervical lymphadenopathy and elevated liver enzymes[4]. Several reports have shown that CMV can cause severe disease in immunocompromised patients; for instance, patients that have been treated with steroids, have renal failure, acquired immune deficiency syndrome, cancer or IBD, or have undergone bone marrow or solid tumor transplants[3,5-7]. A meta-analysis of CMV colitis among immunocompetent patients was performed by Galiatsatos et al[4] and included 44 cases over 23 years. Only three case reports have been written by Japanese researchers on CMV colitis after ischemic colitis in immunocompetent patients.

In our case, abdominal pain, a typical symptom of ischemic colitis, was not detected. Although the symptoms with no abdominal pain are atypical in ischemic colitis, colonoscopy results, location of the disease and biopsy results were in accordance with ischemic colitis. Patients with diabetes mellitus often have a nerve disorder and at times do not feel pain, even in the presence of myocardial infarction. Our patient was old and also had a history of diabetes mellitus, providing a potential explanation for why abdominal pain was not detected.

CMV target organs include the gastrointestinal tract, lung, retina, liver and central nervous system[4]. CMV can infect the gastrointestinal tract from the esophagus to the rectum, with the most frequent site in immunocompetent patients being the colon. These data are in concordance with those reported by Galiatsatos et al[4]. The symptoms of CMV colitis include abdominal pain, anorexia, malaise, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and bleeding[5]. Colonic perforation, although uncommon (about 1% of cases), is a potentially fatal complication in these patients.

Colonoscopy can reveal a range of CMV colitis related findings, such as shallow, erythematous erosions or localized ulcers and, less commonly, plaques, nodules and polyps. Biopsies are essential because similar findings can be present in other types of colitis. Pathological examination of the involved gastrointestinal site typically reveals diffuse ulcerations and necrosis with scattered CMV inclusions that play an active role in damaging the colonic mucosa, primarily as a result of CMV vasculitis[6]. These characteristics are consistent with our patient’s pathological findings.

Previously, diagnosing CMV infection required at least one of the following laboratory methods: serology, direct detection of CMV pp65 antigen in the blood or CMV culture. Increase in the serum anti-CMV IgM and IgG levels indicates a recent or a past CMV infection, respectively. Although anti-CMV IgG and IgM serum levels have been previously widely used at diagnosis of CMV infection, serology and virus detection tests are not very sensitive and may not detect the virus despite disease progression. Culturing CMV from body fluids or tissue samples is another method, although a time-consuming one with low sensitivity. Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining and immunohistochemical staining appear to be more sensitive than serological or virus isolation tests[2]. The HE sensitivity is 10%-87%[8] and CMV inclusion bodies can be found in biopsy specimens. Recent usage of PCR assay to detect CMV-DNA has led to successful diagnosis; however, the technology is not commonly available[9]. Therefore, the final diagnosis relies on histological findings, including the presence of CMV inclusion bodies, and the immunohistochemistry or hybridization results. In our case, there was an increase in the levels of anti-CMV IgG antibodies despite CMV pp65 antigen being negative. Histological findings showed CMV inclusion bodies detected in HE staining. Immunohistochemical staining was positive. PCR detection was not performed.

Two theories, the primary and secondary, have been proposed regarding the mechanism of the pathogenesis of CMV colitis. The primary theory is that the CMV can proliferate in the vascular endothelial cells, leading to vasculitis and small vessel thrombosis with local ulceration[7]. Furthermore, large vessel vasculitis may lead to thrombosis and subsequently to ischemic colitis. According to the secondary theory, previous diseases, such as ischemic colitis or IBD, destroy the colonic mucosa, leading to local immunosuppression. CMV infection may occur under such mucosal conditions. In the case of our patient, severe ischemic colitis preceded CMV infection that was allowed to be established due to the disruption of the colonic mucosa by the prior ischemic colitis. CMV inclusion bodies were detected at the second follow-up colonoscopy but not at the first colonoscopy.

Ganciclovir is currently a standard anti-viral drug for the treatment of CMV infection. Both ganciclovir and foscarnet have shown to significantly improve the prognosis of CMV disease of the gastrointestinal tract[6]. Unfortunately, ganciclovir can lead to serious side effects, including myelosuppression, central nervous system disorders, hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity[2]. Despite these serious side effects, Eddleston recommended antiviral therapy for immunocompetent patients due to poor prognosis in the absence of antiviral treatment[10].

In our patient, CMV colitis prolonged ischemic colitis and colonoscopy showed severe colitis symptoms. We correctly diagnosed CMV colitis with positive immunohistochemical staining. Implementation of intravenous ganciclovir therapy led to considerable healing and disappearance of positive immunohistochemical staining. No ganciclovir-related side effects were detected. Concerning the stenosis detected by colonoscopy, we plan to operate or place a stent in this stenosis when complete obstruction is noticed at this area.

A secondary CMV infection must be suspected when prolonged ischemic colitis is noted following conservative therapy. Biopsies or PCR tests may be necessary to diagnose CMV colitis. CMV colitis may be the cause of more cases of intractable ischemic colitis than are currently being documented.

An 86-year old woman presented with one day episodes of vomiting and diarrhea.

A day after admission, diarrhea and vomiting decreased but diarrhea changed into hematochezia without abdominal pain.

Colon cancer, ischemic colitis, bleeding of diverticulum.

C-reactive protein, 0.45 mg/dL; lactate dehydrogenase, 346 U/L; creatinine phosphokinase, 241 U/L; creatinine, 0.90 mg/dL; fasting blood sugar, 190 mg/dL; complete blood counts and liver functions were within normal range.

The first colonoscopy showed acute, inflamed, friable mucosal changes, while the second colonoscopy detected that these findings were prolonged.

Colonoscopy and biopsy revealed cytomegalovirus (CMV) colitis followed by ischemic colitis, CMV positive.

The patient was treated with intravenous ganciclovir.

CMV infection is common in adults and most infected adults do not show symptoms. However, gastrointestinal CMV disease usually occurs in immunocompromised patients.

“Immunocompetent” means patients have normal immunity.

This case report suggests that a biopsy may be necessary to detect CMV when intractable ischemic colitis is observed.

This case report demonstrates application of the clinical and endoscopic methods to diagnose cytomegalovirus colitis and strongly recommends prompt management of cytomegalovirus in immunocompetent patients.

P- Reviewer: Fan H, Suzuki H, ul Bari S S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | de la Hoz RE, Stephens G, Sherlock C. Diagnosis and treatment approaches of CMV infections in adult patients. J Clin Virol. 2002;25 Suppl 2:S1-12. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Rafailidis PI, Mourtzoukou EG, Varbobitis IC, Falagas ME. Severe cytomegalovirus infection in apparently immunocompetent patients: a systematic review. Virol J. 2008;5:47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Papadakis KA, Tung JK, Binder SW, Kam LY, Abreu MT, Targan SR, Vasiliauskas EA. Outcome of cytomegalovirus infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2137-2142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Galiatsatos P, Shrier I, Lamoureux E, Szilagyi A. Meta-analysis of outcome of cytomegalovirus colitis in immunocompetent hosts. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:609-616. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Gorsane I, Aloui S, Letaif A, Hadhri R, Haouala F, Frih A, Dhia NB, Elmay M, Skhiri H. Cytomegalovirus ischemic colitis and transverse myelitis in a renal transplant recipient. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2013;24:309-314. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Chang HR, Lian JD, Chan CH, Wong LC. Cytomegalovirus ischemic colitis of a diabetic renal transplant recipient. Clin Transplant. 2004;18:100-104. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Lee CJ, Lian JD, Chang SW, Chou MC, Tyan YS, Wong LC, Chang HR. Lethal cytomegalovirus ischemic colitis presenting with fever of unknown origin. Transpl Infect Dis. 2004;6:124-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yi F, Zhao J, Luckheeram RV, Lei Y, Wang C, Huang S, Song L, Wang W, Xia B. The prevalence and risk factors of cytomegalovirus infection in inflammatory bowel disease in Wuhan, Central China. Virol J. 2013;10:43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Numata S, Nakamura Y, Imamura Y, Honda J, Momosaki S, Kojiro M. Rapid quantitative analysis of human cytomegalovirus DNA by the real-time polymerase chain reaction method. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:200-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Eddleston M, Peacock S, Juniper M, Warrell DA. Severe cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:52-56. [PubMed] |