Published online Mar 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i11.3337

Peer-review started: September 25, 2014

First decision: October 14, 2014

Revised: November 3, 2014

Accepted: December 8, 2014

Article in press: December 8, 2014

Published online: March 21, 2015

Processing time: 177 Days and 7.4 Hours

AIM: To investigate whether screening for gallstone disease was economically feasible and clinically effective.

METHODS: This clinical study was initially conducted in 2002 in Taipei, Taiwan. The study cohort total included 2386 healthy adults who were voluntarily admitted to a regional teaching hospital for a physical check-up. Annual follow-up screening with ultrasound sonography for gallstone disease continued until December 31, 2007. A decision analysis using the Markov Decision Model was constructed to compare different screening regimes for gallstone disease. The economic evaluation included estimates of both the cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of screening for gallstone disease.

RESULTS: Direct costs included the cost of screening, regular clinical fees, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and hospitalization. Indirect costs represent the loss of productivity attributable to the patient’s disease state, and were estimated using the gross domestic product for 2011 in Taiwan. Longer time intervals in screening for gallstone disease were associated with the reduced efficacy and utility of screening and with increased cost. The cost per life-year gained (average cost-effectiveness ratio) for annual screening, biennial screening, 3-year screening, 4-year screening, 5-year screening, and no-screening was new Taiwan dollars (NTD) 39076, NTD 58059, NTD 72168, NTD 104488, NTD 126941, and NTD 197473, respectively (P < 0.05). The cost per quality-adjusted life-year gained by annual screening was NTD 40725; biennial screening, NTD 64868; 3-year screening, NTD 84532; 4-year screening, NTD 110962; 5-year screening, NTD 142053; and for the control group, NTD 202979 (P < 0.05). The threshold values indicated that the ultrasound sonography screening programs were highly sensitive to screening costs in a plausible range.

CONCLUSION: Routine screening regime for gallstone disease is both medically and economically valuable. Annual screening for gallstone disease should be recommended.

Core tip: The results of this economic evaluation of screening for gallstone disease indicated that routine ultrasound sonography screening is worthwhile. We recommend that the Chinese population is screened annually for gallstone disease, regardless of whether or not they have been diagnosed with gallstone disease in the past.

- Citation: Shen HJ, Hsu CT, Tung TH. Economic and medical benefits of ultrasound screenings for gallstone disease. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(11): 3337-3343

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i11/3337.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i11.3337

Gallstone disease (GSD) is a common gastrointestinal disease, and > 14% of adults are affected by this disorder[1,2]. In the United States, the direct and indirect economic cost of treating GSD patients has been estimated at USD 16 billion annually, and GSD annually accounts for > 800000 hospitalizations[3,4]. Cholecystectomy is considered to be a safe treatment of choice for symptomatic GSD patients[2,5]. Nevertheless, depending on the clinical manifestations of the disease and changes in symptoms over time, expectant management might also present a valid therapeutic approach for certain GSD patients[2]. From the clinical viewpoint, early detection of the disorder through regular ultrasound sonography screening, followed by appropriate treatment regime, could avert the need for cholecystectomy.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is widely accepted in developed countries as the first line of treatment for uncomplicated GSD. Up to 80% of cholecystectomies are laparoscopies in such countries[6,7], which are relatively safe (mortality is < 0.2% and morbidity < 5.0%) and are highly acceptable to both patients and physicians[2,8]. In addition, previous study also indicated that laparoscopic cholecystectomy is associated with a significantly shorter hospital stay and quicker convalescence compared with open cholecystectomy[2].

GSD is an important health problem, therefore, it is matched to the Wilson criteria for routine screening. This means that the disease natural course should be understood; a recognizable latent or early symptomatic stage; a clinical test is easy to perform and interpret, reliable, accurate, acceptable, sensitive and specific; an accepted treatment recognized for the disease; it is more effective if treatment is started early; a policy on who should be treated; diagnosis and treatment are cost-effective; and case-finding should be a continuous process. The costs of screening programs and early treatment for GSD might be offset by these benefits if the early treatment was known to reduce the incidence of the disease or slow its progression and reduce the need for cholecystectomy. However, relevant cost analyses did not consider the natural history of GSD, and therefore, might have provided inaccurate estimations. The unique medical environment of Taiwan requires careful analysis of the costs and benefits before firm conclusions can be drawn and standards set. Our previous study indicated that compared with the control group, routine screening strategies for GSD reduced the necessity of cholecystectomy by approximately the following amounts: annual screening 82.9% 95%CI: 75.7%-90.4%); biennial screening 71.6% (95%CI: 57.0%-88.8%); 3-year screening 64.8% (95%CI: 46.1%-81.5%); 4-year screening 49.6% (95%CI: 23.9%-75.3%); and 5-year screening 32.1% (95%CI: -2.8%-66.7%)[9]. In this study, we further investigated whether a routine ultrasound sonography screening program is a cost-effective strategy for managing GSD in the Chinese population in Taiwan.

We recruited a study cohort to evaluate the economic implications of GSD screening in Taipei, Taiwan. The initial study cohort comprised 2386 healthy adults (1235 men and 1151 women) who were voluntarily admitted to a regional teaching hospital in Northern Taiwan to receive a physical check-up. The study was initially conducted between January and December 2002. Annual follow-up screenings for GSD continued until December 31, 2007. We analyzed information on patients who received at least two GSD screenings.

One thousand and seven (42.2%) patients in the original study group failed to complete the entire assessment series. Participants who were lost to follow-up during the 5-year period showed the following characteristics compared to those who remained: more advanced age (50.2 ± 10.8 years vs 45.0 ± 9.9 years, P < 0.0001), higher systolic blood pressure [(SBP); 127.9 ± 21.0 mmHg vs 120.7 ± 19.1 mmHg, P < 0.0001)], and higher fasting plasma glucose (102.6 ± 25.1 mg/dL vs 95.2 ± 24.0 mg/dL, P < 0.0001). All study procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of our Institutional Ethics Committee and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The data from all participants remained anonymous. Access to personal demographic and medical records was approved by the Human Subjects Review Board at Cheng-Hsin General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan.

In the present study, GSD was diagnosed by a panel of specialists using real-time ultrasound sonography (nemio SSA-550A; Toshiba, Japan). The abdominal region of the patients was examined after they had fasted for ≥ 8 h, and sonography was used to identify movable hyperechoic foci with acoustic shadows. The diagnosis of GSD was classified as follows: single gallbladder stone; multiple gallbladder stones; and gallstones requiring cholecystectomy. Gallbladder polyps were not included. The study cases were identified among all types of GSD patients[10].

To determine consistent criteria for the diagnosis of GSD, the κ statistic was further used to evaluate the inter-observer reliability among various medical specialists. A pilot study was performed using the data of 100 randomly selected healthy participants; none of our patients were included in this stage. The κ value of the inter-observer reliability for the diagnosis of GSD among the medical specialists was 0.79 (95%CI: 0.61-0.95)[10].

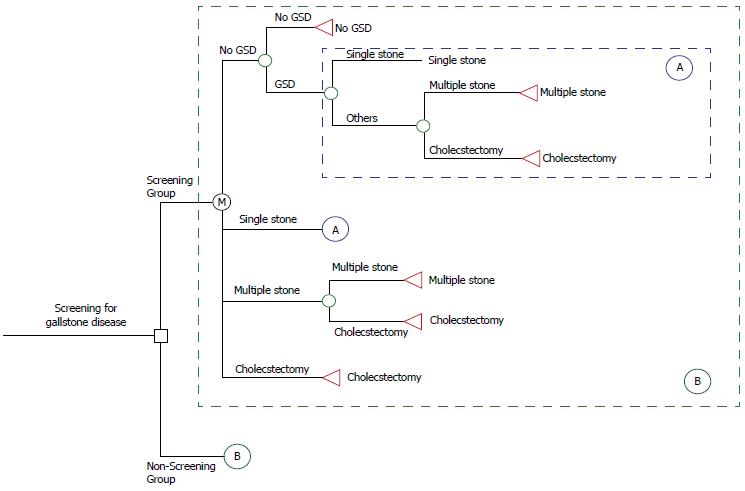

Markov decision model of screening for GSD: Decision tree analysis is a statistical technique used for selecting an optimal decision rule. A study problem is formulated in a tree-structured format, including the decision node (□), chance node (〇), and value node (△). An expected value for each node is calculated, and the best decision is selected based on the expected values[11]. The economic evaluation tool in this study used to assess the GSD screening was on the basis of TreeAge software (DATA 3.5, Tree-Age, Inc., Williamstown, MA, United States) for medical decision analyses. This software uses the influence diagram approach and tree structure.

As Figure 1 shows, a decision analysis using the Markov Decision Model was constructed to compare various screening regimens for GSD with no screening group. The assumption of the no-screening group was that except for GSD screening, patients still received routine medical care until they received a cholecystectomy. According to stochastic process theory, the Markov Chain Model is determined by both the initial state and the transition matrix. This model starts with the decision to screen or not to screen a patient, and the overall expected value is based on the expected values of the end nodes rather than all nodes. As Circle A shows in Figure 1, four states of the natural history of GSD are possible for each decision, that is, no GSD, single stone, multiple stones, and requiring cholecystectomy. The initial state distribution is based on the results of this study. Transition probabilities from one state to another, representing the natural course of GSD, were derived by our previous empirical estimation. In addition, the Circle B indicated that the same disease process with Markov property between the screening and non-screening groups. For each scenario, the expected probability based on participants’ aggregate experiences, using data accumulated for each stage during the 10-year follow-up were calculated.

Cost estimation: Both the direct and indirect costs both were analyzed. Direct costs included the cost of GSD screening, cost of regular clinical fees, and further treatment costs. For indirect costs, we included only the loss of productivity for the patient because of time off work for treatment. Due to the fact that participants were not accompanied every time by an attendant, the cost of an attendant was not considered. The average time off work for treatment was estimated by the specialists. All costs are expressed in new Taiwan dollars (NTD).

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) and cost-utility analysis (CUA): We conducted a CEA to compare the cost per life-year gained by the screened patients relative to the non-screened group. To adjust for quality of life, a series of utility scores was assigned based on the CUA, as follows: no GSD, single stone, multiple stones, and requiring cholecystectomy. The time trade-off method was used to evaluate the utility value according to a standard procedure with modification[12]. A scenario was described to the participants as follows: “Imagine a situation in which you could live for 10 years with your current health status. Now imagine you were given the opportunity to restore your health status to perfect health. This opportunity could increase your quality of life, but would also decrease your chance of survival. What is the maximum number of years you would be willing to forgo so that you could receive this opportunity and have the best health for the remainder of your life?”

Then the utility value was calculated as follows: the number of years a patient was willing to trade in return for improving one’s health, divided by the estimated number of years of remaining life, followed by subtracting this number from 1.0, that is, the utility value = 1.0 - (time traded/time of remaining life)[12,13]. The CUA approach was then used to compare the cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained between the screened and non-screened groups.

Sensitivity analysis and discount rate: One-way sensitivity analyses were conducted on individual estimates to assess the effect of screening for GSD on costs, effectiveness, and utility. To account for time preference (i.e., receiving a benefit earlier and incurring the cost later) we discounted all costs and benefits to the present value at 5% annually.

Table 1 shows the annual direct and indirect cost of GSD screening in the decision analysis. Direct costs included the cost of screening (NTD 1382), regular clinical fees (NTD 509), cost of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (NTD 11710), and cost of hospitalization and others (NTD 26825). The total annual direct costs are estimated as NTD 40426. Indirect costs represent the loss of productivity attributable to the patient’s disease state, and were estimated at NTD 635670 using the gross domestic product (GDP) for 2011 in Taiwan. The utility value for no GSD, single stone, multiple stones, and cholecystectomy was 0.92 ± 0.10, 0.90 ± 0.12, 0.89 ± 0.19, and 0.88 ± 0.08, respectively. In addition, the annual transition probabilities from each stage to the next stage were as follows: no GSD to single stone, 5.05%; single stone to multiple stones, 10.00%; and multiple stones to cholecystectomy, 13.76%[9].

| Parameter | Value |

| Annual direct cost (NTD) | |

| Screening cost1 | 1382 |

| Regular clinics fee2 | 509 |

| Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 11710 |

| Hospitalizations and others | 26825 |

| Total | 40426 |

| Annual indirect cost (NTD) | |

| Gross domestic product | 635670 |

| Utility (quality of life) value | |

| No GSD | 0.92 ± 0.10 |

| Single stone | 0.90 ± 0.12 |

| Multiple stones | 0.89 ± 0.19 |

| Cholecystectomy | 0.88 ± 0.08 |

| Annual transition probability (%)[9] | |

| No GSD → Single stone | 5.05 |

| Single stone → Multiple stones | 10.00 |

| Multiple stones → Cholecystectomy | 13.76 |

Table 2 shows the results of CEA for various GSD screening programs during the 10-year follow-up. Annual screening incurred the lowest cost and yielded the greatest effectiveness. The cost per life-year gained (average cost-effectiveness ratio) for annual screening, biennial screening, 3-year screening, 4-year screening, 5-year screening, and control (no-screening) was NTD 39076, NTD 58059, NTD 72168, NTD 104488, NTD 126941, and NTD 197473, respectively. Compared with the non-screened group, the screened groups showed greater effectiveness and lower costs. In other words, any screening program was more cost-effective than no program.

| Screening strategy | Cost (NTD) | Effectiveness(life-years gained) | Cost/effectiveness (NTD) | ICER (compared to control group) | Utility (QALY) | Cost/utility(NTD) | ICUR (compared to control group) |

| Annual | 199856 | 5.1146 | 39076 | Dominate1 | 4.9075 | 40725 | Dominate1 |

| Biennial | 215231 | 3.7071 | 58059 | Dominate1 | 3.3180 | 64868 | Dominate1 |

| 3-yearly | 253908 | 3.5183 | 72168 | Dominate1 | 3.0037 | 84532 | Dominate1 |

| 4-yearly | 331477 | 3.1724 | 104488 | Dominate1 | 2.9873 | 110962 | Dominate1 |

| 5-yearly | 368002 | 2.8990 | 126941 | Dominate1 | 2.5906 | 142053 | Dominate1 |

| Control group | 508117 | 2.5731 | 197473 | - | 2.5033 | 202979 | - |

Table 2 also shows the results after adjusting for utility. Annual screening provided the highest QALY combined with the lowest cost. The cost per QALY gained of annual screening, biennial screening, 3-year, 4-year, and 5-year screenings, and for the no screening was NTD 40725, NTD 64868, NTD 84532, NTD 110962, NTD 142053, and NTD 202979, respectively. Compared with not screening, routine screening provided greater effectiveness at a lower economic cost. Any screening program was more cost-effective than no program at all.

Table 3 shows the sensitivity analysis of CEA and CUA for various GSD screening regimes. The threshold values showed that screening programs were highly sensitive to costs within a plausible range. Compared to no screening, the threshold of CEA in annual screening, biennial screening, 3-yearly screening, 4-yearly screening, and 5-yearly screening was NTD 41630, NTD 38771, NTD 36048, NTD 32186, and NTD 29063, respectively. The screening cost threshold of CUA also decreased with increasing screening interval. For indirect cost and percentage of cholecystectomy, any screening program was more cost-effective than no program.

| Variable | Base case | Range | Threshold of CEA | Threshold of CUA |

| Annual screening | ||||

| Screening cost (NTD) | 1382 | 1000-50000 | 41630 | 40082 |

| Indirect cost (NTD) | 231834 | 0-635670 | Dominate1 | Dominate1 |

| Percentage of cholecystectomy | 0.8 | 0.1-0.9 | Dominate1 | Dominate1 |

| Biennial screening | ||||

| Screening cost (NTD) | 1382 | 1000-50000 | 38771 | 37250 |

| Indirect cost (NTD) | 231834 | 0-635670 | Dominate1 | Dominate1 |

| Percentage of cholecystectomy | 0.8 | 0.1-0.9 | Dominate1 | Dominate1 |

| 3-yr screening | ||||

| Screening cost (NTD) | 1382 | 1000-50000 | 36048 | 36003 |

| Indirect cost (NTD) | 231834 | 0-635670 | Dominate1 | Dominate1 |

| Percentage of cholecystectomy | 0.8 | 0.1-0.9 | Dominate1 | Dominate1 |

| 4-yr screening | ||||

| Screening cost (NTD) | 1382 | 1000-50000 | 32186 | 31952 |

| Indirect cost (NTD) | 231834 | 0-635670 | Dominate1 | Dominate1 |

| Percentage of cholecystectomy | 0.8 | 0.1-0.9 | Dominate1 | Dominate1 |

| 5-yr screening | ||||

| Screening cost (NTD) | 1382 | 1000-50000 | 29063 | 28579 |

| Indirect cost (NTD) | 231834 | 0-635670 | Dominate1 | Dominate1 |

| Percentage of cholecystectomy | 0.8 | 0.1-0.9 | Dominate1 | Dominate1 |

The well-known factors related to GSD include type 2 diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome[14-19]. The presence of metabolic syndrome as an insulin resistance phenotype is related to increased morbidity in GSD[19,20]. A previous study showed that both asymptomatic and symptomatic GSD patients displayed a benign natural history. The majority of patients with severe or mild symptoms no longer experienced biliary pain during follow-up, and the rate of symptom development in asymptomatic patients was low[2]. However, participants with GSD showed increased rates of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality compared with no GSD. This relationship was found among patients in the United States who were either diagnosed with GSD after an ultrasound scan, or who had received a cholecystectomy. The association was largely unexplained by multiple demographic and cardiovascular disease risk factors in this population[21]. One case-control study in Sweden revealed that more than twice as many young women who had died of cancer had received a cholecystectomy than women who had died from other causes[22]. Another study that used a progressive disease model to describe the natural history of GSD reported that the estimated mean duration for the stages of no GSD, single stone, and multiple stones was 18.18 years, 8.77 years, and 6.76 years, respectively[9]. Based on these findings, if we assume that no patients progressed directly from having a single gallstone to receiving a cholecystectomy, the average time to progress from no GSD to requiring a cholecystectomy is about 33.7 years for the general population. This slow progression indicates that clinicians should be able to detect single or multiple stones at an early stage, and thus, reduce GSD-related mortality.

Currently, it is under discussion if cholecystectomy is suggested for patients with asymptomatic GSD. However, in symptom-free patients, it is generally conceived that surgical procedures are not recommended[23].

Evidence-based studies have suggested that screening for and treating GSD is extremely cost-effective. In Chile, a screening program for GSD in a high-risk population achieved significant benefits at low incremental costs and acceptable cost-effectiveness. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratios were as follows: universal screening and elective intervention, NTD 180; high-risk intervention, NTD 147; and selective screening strategy, NTD 481[24]. Considering both cost and efficacy, prevention programs that screened for GSD resulted in substantial federal budget savings combined with highly cost-effective health care. In the present study, the CEA and CUA showed that annual GSD screening was the most effective and efficient screening schedule. Thus, the safest and most aggressive approach to preventing GSD should include annual screening. In addition, professionals responsible for establishing standards for the quality of health care must consider the marginal benefit of frequent ultrasound sonography examinations.

Economic evaluations are commonly criticized by decision makers for ignoring budgetary constraints, which are of prime concern to decision makers. Stakeholders might encounter financial difficulties if they adopt too many cost-effective interventions in which the affordability of a program depends on the overall volume of patients[2,25]. From a clinical perspective, the annual cost of screening for GSD (including clinician fees and ultrasound examinations) is relatively low per patient at USD 29.35 or NTD 882. Our results showed that an annual screening regimen could offer greater cost-effectiveness than any longer screening intervals. However, long-term follow-up might be affected by difficulties in maintaining contact with patients; such patients might be unlikely to remember to schedule an examination after several years have passed.

The use of primary data and the calculation of both direct and indirect costs allowed us to estimate the true benefit of GSD screening more accurately than in previous studies. Nonetheless, this study was subject to certain limitations. First, we did not explicitly consider the sensitivity and specificity of the GSD screening. A greater understanding of GSD from the asymptomatic to the symptomatic stage and the ideal conditions for screening would help to determine the optimal frequency of sonography check-ups and the sensitivity and specificity of this screening tool. Second, although the κ value for inter-observer reliability appeared adequate[26], non-differential misclassification-bias identification might have influenced the results. Third, potential self-selection bias might have occurred because our study design was hospital-based and the follow-up rate was relatively low (57.8%). This is more likely caused by non-respondents with older ages and severe SBP and fasting plasma glucose than participants, that is, of it not being exactly representative of the whole general population. Fourth, because laparoscopic cholecystectomy is not performed routinely for GSD (only polyp > 1 cm), further studies will be needed to explore cholecystectomy (this study recommended it only in cases with multiple stones): such as patients with cholecystitis who required cholecystectomy with one stone or no stone. Finally, our sample size was too small to estimate certain variables that would likely affect the optimal screening intervals for GSD. These variables include comorbidity (e.g., obesity or type 2 diabetes), influence of GSD development over time and among various age groups on the stage of disease, and the occurrence of complications. Further long-term studies should be conducted to clarify whether patients whose weight is well controlled, or those at an early stage of GSD, would benefit from the least frequent screening interval.

In conclusion, the results of our economic evaluation of GSD screening suggested that screening is worthwhile. We recommend that Chinese people are screened annually for GSD, regardless of whether or not they have been diagnosed with GSD in the past.

Gallstone disease (GSD) is an important health problem, therefore, it is matched to the Wilson criteria for routine screening. The authors investigated whether a routine ultrasound sonography screening program is a cost-effective strategy for managing GSD in the Chinese population in Taiwan.

The costs of screening programs and early treatment for GSD might be offset by these benefits if early treatment reduces the incidence of the disease or slows its progression and reduces the need for cholecystectomy.

Longer time intervals in screening for GSD were associated with reduced efficacy and utility of screening and with increased cost. The cost per life-year gained (average cost-effectiveness ratio) for annual screening, biennial screening, 3-year screening, 4-year screening, 5-year screening, and no-screening was NTD 39076, NTD 58059, NTD 72168, NTD 104488, NTD 126941, and NTD 197473, respectively (P < 0.05). The cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained by annual screening, NTD 40725; biennial screening, NTD 64868; 3-year screening, NTD 84532; 4-year screening, NTD 110962; 5-year screening, NTD 142053; and for the control group, NTD 202979 (P < 0.05). The threshold values indicated that the ultrasound sonography screening programs were highly sensitive to screening costs in a plausible range.

The results of the present economic evaluation of GSD screening suggested that screening is worthwhile. The authors recommend that Chinese people are screened annually for GSD, regardless of whether or not they have been diagnosed with it in the past.

Considering both cost and efficacy, prevention programs that screened for GSD resulted in substantial federal budget savings combined with highly cost-effective health care. In this study, the cost-effectiveness analysis and cost-utility analysis showed that annual GSD screening was the most effective and efficient screening schedule. Thus, the safest and most aggressive approach to preventing GSD should include annual screening.

This manuscript purports to show that there are economic and medical benefits from ultrasound screening for gallstones. Using a Markov Decision model they calculated QALY gained by different screening regimens. The authors can clarify if the patients were accompanied every time by an attendant. If yes, then cost and wages lost of the attendant has to also be taken into consideration. Or else the authors can state that attendant was not required.

P- Reviewer: Kang JY, Sureka B, Vasilescu A S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Kerr C E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Portincasa P, Moschetta A, Palasciano G. Cholesterol gallstone disease. Lancet. 2006;368:230-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 554] [Cited by in RCA: 490] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Festi D, Reggiani ML, Attili AF, Loria P, Pazzi P, Scaioli E, Capodicasa S, Romano F, Roda E, Colecchia A. Natural history of gallstone disease: Expectant management or active treatment? Results from a population-based cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:719-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Everhart JE, Khare M, Hill M, Maurer KR. Prevalence and ethnic differences in gallbladder disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:632-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 549] [Cited by in RCA: 539] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zacks SL, Sandler RS, Rutledge R, Brown RS. A population-based cohort study comparing laparoscopic cholecystectomy and open cholecystectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:334-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Roda E, Festi D, Lezoche E, Leuschner U, Paugartner G, Sauerbruch T. Strategies in the treatment of biliary stones. Gastroenterol Int. 2000;13:7-15. |

| 6. | Teerawattananon Y, Mugford M. Is it worth offering a routine laparoscopic cholecystectomy in developing countries? A Thailand case study. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2005;3:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hobbs MS, Mai Q, Fletcher DR, Ridout SC, Knuiman MW. Impact of laparoscopic cholecystectomy on hospital utilization. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:222-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement on Gallstones and Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 1993;165:390-398. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Hsu CT, Lien SY, Jiang YD, Liu JH, Shih HC, Tung TH. Screening gallstone disease by ultrasound decreases the necessity of cholecystectomy. Asia Life Sci. 2013;22:51-60. |

| 10. | Liu CM, Tung TH, Chou P, Chen VT, Hsu CT, Chien WS, Lin YT, Lu HF, Shih HC, Liu JH. Clinical correlation of gallstone disease in a Chinese population in Taiwan: experience at Cheng Hsin General Hospital. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1281-1286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tung TH, Shih HC, Chen SJ, Chou P, Liu CM, Liu JH. Economic evaluation of screening for diabetic retinopathy among Chinese type 2 diabetics: a community-based study in Kinmen, Taiwan. J Epidemiol. 2008;18:225-233. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Brown MM, Brown GC, Sharma S, Shah G. Utility values and diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:324-330. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Brown MM, Brown GC, Sharma S, Busbee B, Brown H. Quality of life associated with unilateral and bilateral good vision. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:643-647; discussion 647-648. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Chien WH, Liu JH, Hou WY, Shen HJ, Chang TY, Tung TH. Clinical implications in the incidence and associated risk factors on gallstone disease among elderly type 2 diabetes in Kinmen, Taiwan. Int J Gerontol. 2014;8:95-99. |

| 15. | Chen JY, Hsu CT, Liu JH, Tung TH. Clinical predictors of incident gallstone disease in a Chinese population in Taipei, Taiwan. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Grundy SM. Metabolic syndrome scientific statement by the American Heart Association and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2243-2244. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735-2752. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Eckel RH, Alberti KG, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2010;375:181-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in RCA: 791] [Article Influence: 52.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chen LY, Qiao QH, Zhang SC, Chen YH, Chao GQ, Fang LZ. Metabolic syndrome and gallstone disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4215-4220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cojocaru C, Pandele GI. [Metabolic profile of patients with cholesterol gallstone disease]. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2010;114:677-682. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Gallstone disease is associated with increased mortality in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:508-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lowenfels AB, Domellöf L, Lindström CG, Bergman F, Monk MA, Sternby NH. Cholelithiasis, cholecystectomy, and cancer: a case-control study in Sweden. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:672-676. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Portincasa P, Ciaula AD, Bonfrate L, Wang DQ. Therapy of gallstone disease: What it was, what it is, what it will be. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2012;3:7-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 24. | Puschel K, Sullivan S, Montero J, Thompson B, Díaz A. [Cost-effectiveness analysis of a preventive program for gallbladder disease in Chile]. Rev Med Chil. 2002;130:447-459. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Ubel PA, Hirth RA, Chernew ME, Fendrick AM. What is the price of life and why doesn’t it increase at the rate of inflation? Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1637-1641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 465] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Byrt T. How good is that agreement? Epidemiology. 1996;7:561. [PubMed] |