Published online Mar 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i11.3282

Peer-review started: September 15, 2014

First decision: October 14, 2014

Revised: October 24, 2014

Accepted: December 1, 2014

Article in press: December 1, 2014

Published online: March 21, 2015

Processing time: 185 Days and 18.2 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the outcome of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNFα) therapy in outpatients with ulcerative colitis at a tertiary referral center.

METHODS: All patients with a confirmed diagnosis of ulcerative colitis undergoing therapy with infliximab and/or adalimumab at the outpatient clinic for inflammatory bowel diseases at the University Hospital Heidelberg between January 2011 and February 2014 were retrospectively enrolled. Patients with a follow-up period of less than 6 mo from start of anti-TNFα therapy were excluded. Medical records of all eligible individuals were carefully reviewed. Steroid-free clinical remission of a duration of at least 3 mo, colectomy rate, duration of anti-TNFα therapy, need for anti-TNFα dose escalation, and the occurrence of adverse events were evaluated as the main outcome parameters.

RESULTS: Seventy-two patients were included (35 treated with infliximab, 17 with adalimumab, 20 with both consecutively). Median follow-up was 27 mo (range: 6-87 mo). Steroid-free clinical remission was achieved by 22.2% of the patients (median duration: 21 mo until end of follow-up; range: 3-66 mo). Patients attaining steroid-free clinical remission displayed lower hemoglobin and albumin blood levels at the start of treatment than those who did not achieve remission. The overall colectomy rate was 20.8%. Nearly 50% of the patients underwent anti-TNFα dose escalation during the follow-up period. For both the infliximab and the adalimumab treated patients, non-response to anti-TNFα therapy was the major reason for treatment discontinuation. 18.2% of the infliximab-treated patients and 13.5% of the adalimumab-treated patients had to discontinue their therapy due to adverse events.

CONCLUSION: Real-life remission rates of ulcerative colitis under anti-TNFα are overall low, but some patients have a clear long-term benefit.

Core tip: Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors are a widely accepted therapeutic option for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Results from different real-life settings on their use in ulcerative colitis are controversial. Weighing anti tumor necrosis factor alpha against other treatment options, it is very important to decide on the best therapy for a patient. This retrospective study from a tertiary referral centre shows a rate of steroid-free clinical remission of 22.2% and a colectomy rate of 20.8% for ambulatory patients with ulcerative colitis under therapy with tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors. These rather disappointing outcomes should be thoroughly discussed with the patients before start of therapy.

- Citation: Baki E, Zwickel P, Zawierucha A, Ehehalt R, Gotthardt D, Stremmel W, Gauss A. Real-life outcome of anti-tumor necrosis factor α in the ambulatory treatment of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(11): 3282-3290

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i11/3282.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i11.3282

Despite considerable progress over the past decades, treatment options for ulcerative colitis (UC) are still unsatisfactory. Realistically attainable remission rates are far below the goals set, and long-term remission remains elusive. The introduction of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) inhibitors into the therapy of Crohn’s disease revolutionized its treatment[1-5]. Infliximab (IFX) and adalimumab (ADA) were the first anti-TNFα agents to be also approved for induction and maintenance of remission in UC[6,7]. The ACT-1 and ACT-2 studies evaluated the efficacy of IFX for induction and maintenance therapy in adults with UC[6]. Remission rates at week 8 were at 38.8% in ACT-1 and 33.9% in ACT-2[6]. Rates of sustained remission (at week 8 and week 30) were even lower at 26.2% (ACT-1) and 22.5% (ACT-2)[6]. Results of the phase III trials of ADA were slightly less promising: at week 8, 18.5% of the patients in the high-dose group were in remission, compared with 9.2% in the placebo group[7]. The recently approved TNFα inhibitor golimumab was also shown to induce and maintain clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe UC[8,9].

Post-marketing experience reveals inconsistent results. Armuzzi et al[10] found remission rates of 17%, 28.4%, 36.4% and 43.2% at 4, 12, 24 and 54 wk in 88 patients treated with ADA for active UC. Considering that many of their patients had previously been treated with IFX, these results compare favorably to the phase III data cited above[7]. In their retrospective study, Zhou et al[11] described a remarkably high remission rate of 61.5% by week 30 of IFX treatment, but only 24 patients were included in their study. There are no head-to-head clinical trials that compare IFX with ADA in the treatment of UC. However, a recent meta-analysis suggests that IFX, ADA and golimumab are equally effective[12].

Although randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are considered the gold standard for the evaluation of the efficacy of a drug, real-life data provide more insight into factors that might influence therapy outcomes. Therefore, this study was aimed at evaluating firm practical end points of therapy outcomes with TNFα antagonists in a real-life setting, and to identify factors influencing the efficacy of the treatment. It was not the objective of this study to compare outcomes of IFX therapy with those of ADA therapy.

This is an uncontrolled, open-label retrospective study of outpatients with moderate or severe UC at a German university hospital serving as a tertiary referral center for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Heidelberg. Inclusion criteria were: a confirmed diagnosis of UC (based on the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation criteria[13]); treatment with IFX or ADA or both consecutively; and a documented follow-up after start of treatment of at least 6 mo.

Patients who changed to the outpatient IBD clinic of the University of Heidelberg after they had started anti-TNFα treatment, patients who had previously undergone intestinal surgery, and patients with acute severe colitis were excluded. All data were retrieved from entirely computerized medical records. To identify eligible individuals, electronically available daily lists of all patients treated in the outpatient IBD clinic between January 1, 2011 and February 28, 2014 were screened. Patients who had started anti-TNFα treatment at our outpatient clinic prior to January 1, 2011, but were treated within the time frame of the study, were also included. Demographic and clinical parameters of all eligible individuals were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. At the IBD outpatient unit, patients under anti-TNFα therapy are routinely examined by a gastroenterologist 6 and 12 wk after the start of therapy, and every 3 mo thereafter. IFX was delivered via intravenous (IV) infusions (5 mg/kg body weight) at weeks 0, 2 and 6. After that, patients received scheduled infusions (5 mg/kg body weight) every 8 wk, if no dose intensification was deemed necessary. ADA was delivered by subcutaneous injections of 80 mg at days 1, 2 and 14, and then 40 mg every other week as long as no dose escalation was required. In this study, blood concentrations of IFX and ADA and anti drug antibodies were not measured, so that decisions on dose escalation were mainly based on the patients’ symptoms.

The Montréal classification for UC was applied to categorize disease extent[14]. Steroid-free clinical remission was defined by the absence of diarrhea (≥ 4 bowel movements per day), bloody stools and abdominal pain without intake of steroids for at least 3 mo, as evaluated by the treating physician. In our study, response was not employed as an outcome parameter, as variables for the calculation of reliable disease activity scores had not been documented precisely enough in our sample of patients. The decision to discontinue therapy due to inadequate response was in all cases made by a senior gastroenterologist. Dose escalation of anti-TNFα therapy involved a reduction of the IFX dosing interval to at least 4 wk and/or an increase of the dose to at most 10 mg/kg body weight. For ADA, dose escalation meant shortening of the dosing interval to at least 7 d. The decision on dose intensification was left to the treating physician’s judgment. Primary non-response was defined as absence of amelioration of UC symptoms up to 3 mo of treatment. Concomitant immunosuppressive treatment was considered if a patient was on immunomodulators for at least 3 mo after start of anti-TNFα therapy.

The primary end point was the induction of steroid-free clinical remission under anti-TNFα therapy. Secondary end points were the need for colectomy within the follow-up period, discontinuation of therapy due to insufficient efficacy, discontinuation of treatment due to adverse events, and need for dose escalation according to the treating physician’s judgment. Patients were not followed up if they left the outpatient clinic to change to a different treatment center or practice. Therefore, colectomy rates could only be calculated for the time that the patients stayed at our outpatient clinic.

Further information retrieved from the electronic patient charts comprised gender, age, disease duration, body mass index (BMI), family history of IBD, presence of extraintestinal manifestations, smoking habits, prior and concomitant medications, side effects under anti-TNFα therapy, and laboratory markers before and after start of therapy, including blood cell counts, plasma ferritin, C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum albumin levels.

As this is a retrospective study, disease activity scores were not consistently available. As a surrogate, we analyzed single variables which occur in commonly used UC activity scores, and which were routinely asked by the treating physician and documented in the computerized charts. These included numbers of bowel movements per 24 h and the occurrence of bloody stools. They were evaluated at the start of treatment and 3 mo after the start of treatment.

The objective of the study was to assess anti-TNFα in the treatment of UC, not to compare IFX with ADA. Analyses were performed per patient for outcome parameters like remission and need for colectomy, because one individual cannot appear twice in outcome analysis. Other parameters - like the occurrence of adverse events - were analyzed per therapy. Patients who had received IFX and ADA in either order were additionally evaluated in a separate section. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0. Descriptive statistics were calculated as percentages for discrete variables, and presented as medians with ranges, as appropriate. To identify potential predictors of steroid-free clinical remission, the Mann-Whitney-test was used for ordinal variables, and χ2 tests for categorical variables. Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test was used to compare disease activity markers (except for the occurrence of bloody stools) before and after the start of anti-TNFα therapy. McNemar’s test was used to compare the number of patients reporting the occurrence of blood in stool before and after the start of anti-TNFα therapy. Statistical significance was set at the 95%CI (P < 0.05). To confirm predictors of steroid-free clinical remission, a multivariate, logistic regression analysis was performed. Kaplan-Meier estimator equations were used to compare the survival curves of treatment duration.

In all, 72 patients were enrolled. Thirty-five patients received IFX, 17 underwent treatment with ADA, and 20 patients were on both medications consecutively (15 IFX first, 5 ADA first). The median follow-up time was 27 mo (range, 6-87 mo). All patient demographics and clinical baseline characteristics may be viewed in Table 1.

| Characteristic | |

| Anti-TNFα therapy | |

| IFX only | 35 (48.6) |

| ADA only | 17 (23.6) |

| IFX and ADA | 15 (20.8) |

| ADA and IFX | 5 (6.9) |

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Gender (female:male) | 39: 33 |

| Age at start of treatment (median; range) (yr) | 33 (15-71) |

| Disease extent according to Montréal classification, n (E1:E2:E3) | 5:32:35 |

| Duration of disease at start of anti-TNFα therapy, median (range) (mo) | 69.5 (2-480) |

| Presence of at least one extraintestinal manifestation | 30 (41.7) |

| Smoking status, n (active smokers:non-smokers:ex-smokers) | 6:54:5 (n = 65) |

| BMI, median (range) (kg/m2) | 24.1 (17.3-61.9) (n = 69) |

| Family history of IBD (n positive: n negative) | 5:18 (n = 23) |

| History of colitis medication prior to start of anti-TNFα treatment | |

| Steroids | 70 (97.2) |

| Oral budesonide | 21 (29.2) |

| 5-ASA | 66 (91.7) |

| Azathioprine | 55 (76.4) |

| 6-Mercaptopurine | 3 (4.2) |

| Methotrexate | 12 (16.7) |

| Tacrolimus | 4 (5.6) |

| Cyclosporine | 4 (5.6) |

| Medications concomitant with IFX therapy at start of therapy (n = 55) | |

| Steroids | 37 (67.3) |

| Oral budesonide | 16 (29.1) |

| 5-ASA | 35 (63.6) |

| Azathioprine | 16 (29.1) |

| 6-Mercaptopurine | 1 (1.8) |

| Methotrexate | 3 (5.5) |

| Tacrolimus | 1 (1.8) |

| Cyclosporine | 0 |

| Medications concomitant with ADA therapy at start of therapy (n = 37) | |

| Steroids | 25 (67.6) |

| Oral budesonide | 10 (27.0) |

| 5-ASA | 28 (75.7) |

| Azathioprine | 11 (29.7) |

| 6-Mercaptopurine | 0 (0) |

| Methotrexate | 1 (2.7) |

| Tacrolimus | 0 (0) |

| Cyclosporine | 0 (0) |

Before starting their first anti-TNFα therapy, 66 (91.7%) of the 72 patients had been on oral 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), 21 (29.2%) on oral budesonide, 70 (97.2%) on oral cortisone, 55 (76.4%) on azathioprine (AZA), 3 (4.2%) on 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), 12 (16.7%) on methotrexate (MTX), 4 (5.6%) on tacrolimus, and 4 (5.6%) on cyclosporine. These and the medications concomitant with IFX and ADA treatment are shown in Table 1.

Sixteen patients (22.2%) attained steroid-free clinical remission. Seventy-five percent of these patients were on IFX and 25% were on ADA. The median time to steroid-free clinical remission was 3 mo (range: 1-10 mo). The duration of steroid-free remission was 21 mo (range: 3-66 mo). The median follow-up of the patients attaining remission was 24 mo (range: 6-69 mo). Eleven of the 16 patients (68.8%) were on additional anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive medications when they reached remission: 68.8% took a 5-ASA preparation and 18.8% were on AZA. Eleven of the 16 patients (68.8%) were still treated at our outpatient clinic and in remission at the end of the follow-up period. In 81.3% of all patients achieving remission, the status of steroid-free clinical remission could be maintained for more than one year, in 56.3% for more than 2 years, and in 37.5% for more than 3 years. The rate of steroid-free clinical remission was not related to: patient age at the start of treatment; gender; disease extent according to the Montréal classification; disease duration; the presence of extraintestinal manifestations; smoking status; BMI; family history of IBD; previous treatment with purines, methotrexate or a calcineurin inhibitor; or concomitant therapy with steroids, purines, or 5-ASA (Table 2). Patients with higher plasma CRP concentrations before treatment tended to achieve steroid-free remission more often than those with lower plasma CRP concentrations (P = 0.104; Table 2). Leukocyte and platelet numbers, and plasma ferritin levels at start of treatment did not differ between the remission and the non-remission group. Patients with lower hemoglobin concentrations at the start of treatment achieved remission more frequently than those with higher hemoglobin concentrations (P = 0.023; Table 2). Steroid-free clinical remission was more often induced in patients with lower serum albumin levels at the start of treatment than in those with higher albumin levels (P = 0.009; Table 2).

| Variable | remission (n = 16) | no remission (n = 56) | P value (univariate) | P value (multivariate) |

| Age, (yr) | 32 (15-58) | 34 (18-71) | 0.755 | 0.685 |

| Sex (female: male) | 11:5 | 28:28 | 0.184 | 0.560 |

| Disease extent according to Montréal (E1:E2:E3) | 1:7:8 | 4:25:27 | 0.988 | |

| Disease duration, (mo) | 69.5 (7-288) | 66 (2-480) | 0.968 | 0.873 |

| Patients with extraintestinal manifestations | 6 (37.5) | 24 (42.9) | 0.338 | |

| Smoking (active:non-smokers: ex-smokers) | 2:9:2 (n = 13) | 4:45:3 (n = 52) | 0.318 | |

| BMI, (kg/m2) | 23.9 (18.9-30.8) | 24.2 (17.3-61.9) (n = 53) | 0.654 | 0.546 |

| Previous medications | ||||

| Purine analogons | 14 (87.5) | 42 (75.0) | 0.289 | |

| Methotrexate | 4 (25.0) | 8 (14.3) | 0.310 | |

| Calcineurin inhibitors | 2 (12.5) | 5 (8.9) | 0.671 | |

| Concomitant medications | ||||

| Steroids, (at start of treatment) | 12 (75.0) | 40 (71.4) | 0.778 | |

| 5-ASA | 12 (75.0) | 40 (71.4) | 0.778 | |

| Purine analogons | 4 (25.0) | 20 (35.7) | 0.423 | |

| Laboratory parameters before start of treatment with anti-TNFα | ||||

| CrP, (mg/L) | 7.9 (0-45.3) (n = 14) | 3.1 (0-88.9) (n = 55) | 0.104 | |

| Leukocyte number, (G/L) | 8.8 (3.6-16.6) (n = 14) | 8.8 (2.7-22.0) (n = 55) | 0.817 | |

| Hemoglobin, (g/dl) | 11.3 (8.3-13.9) (n = 14) | 12.4 (9.0-17.0) (n = 55) | 0.023 | 0.561 |

| MCV, (fl) | 82.5 (65-105) (n = 14) | 87 (61-112) (n = 55) | 0.374 | |

| Platelet number, (G/L) | 408 (233-666) (n = 14) | 333 (150-850) (n = 55) | 0.114 | |

| Albumin concentration, (g/L) | 41.5 (26.6-45.1) (n = 9) | 43.9 (36.0-48.8) (n = 44) | 0.009 | 0.034 |

| Ferritin concentration, (μg/L) | 17 (2-201) (n = 8) | 27.5 (5-489) (n = 34) | 0.223 |

During the period that the patients were observed at our clinic, 15 (20.8%) patients underwent colectomy, all due to refractory UC. There were no emergency colectomies. Seven of these patients had been on therapy with IFX alone and eight with subsequent IFX/ADA or ADA/IFX prior to colectomy. The median duration of anti-TNFα therapy before surgery was 9 mo (range: 2-44 mo). Among the patients undergoing colectomy, nine were male and six were female. Their median age was 33 years (range: 19-72 years).

While under both IFX and ADA treatment, surrogates of disease activity changed to the expected directions, the changes were in all small. The only significant differences were realized for the number of bowel movements per 24 h as well as leukocyte numbers in the IFX-treated patients, and platelet numbers in the IFX- and the ADA-treated patients (Table 3).

| Variable | Before start of therapy | 3 mo after start of therapy | P value | |||

| IFX | ADA | IFX | ADA | IFX | ADA | |

| Number of bowel movements per 24 h | 6 (1-30) | 6 (1-17) | 5 (1-40) | 5 (1-20) | 0.042 | 0.229 |

| Occurrence of blood in stool (yes/no) (%) | 32/47 (68) | 23/36 (63.9) | 29/50 (58) | 19/35 (54.3) | 0.678 | 0.453 |

| CRP, (mg/L) | 4.9 (0-51) | 3.6 (0-122) | 2.9 (0-312) | 3.6 (0-145) | 0.310 | 0.435 |

| Leukocyte number (G/L) | 9.4 (2.7-17.6) | 7.7 (2.5-22) | 7.4 (2.2-22.9) | 7.3 (3.9-15.4) | 0.037 | 0.524 |

| Platelet number (G/L) | 338 (150-879) | 335 (194-850) | 307 (166-758) | 298 (170-787) | 0.005 | 0.007 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.2 (8.3-15.9) | 12.4 (8.1-17) | 12.7 (8.5-15.9) | 12.9 (6.4-16.4) | 0.084 | 0.501 |

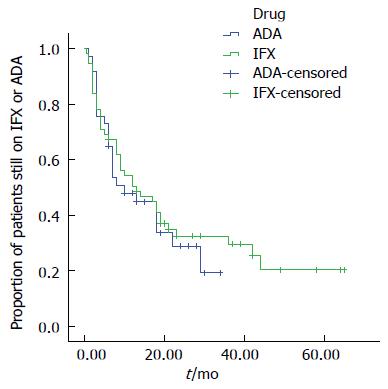

At month 6, 67.3% of the patients receiving IFX were still under treatment, at month 12, 50.5% continued their treatment. Of the patients under ADA therapy, 64.9% were still receiving treatment at month 6, and 47.9% at month 12 (Figure 1).

The reasons for discontinuation of anti-TNFα treatment were grouped into five categories: non-response; loss of response; adverse events; treatment pause in stable remission; or other. Of the 55 patients receiving IFX (including those who had previously been on ADA), 39 (70.9%) discontinued their therapy during the follow-up period after a treatment duration of 8 mo (range: 0.5-44 mo). The reasons were: non-response in 16 patients (41%); loss of response in 12 (30.8%); adverse events in 10 (25.6%); and stable deep remission in one patient (2.6%). Among the 37 patients on ADA (including those who had previously been on IFX), 25 (67.6%) discontinued their therapy after a median treatment duration of 6 mo (range: 1-29 mo). Reasons for discontinuation of treatment with ADA were: non-response in 14 patients (56%), loss of response in 5 patients (20%), adverse events in 5 patients (20%), and pregnancy in one patient (4%).

Among 53 patients who were on steroids at the start of treatment with at least one of the anti-TNFα agents, 23 (43.4%) were able to taper off their steroids completely during anti-TNFα treatment. Of these 23 patients, 14 (60.9%) were successful in tapering under IFX treatment, and 9 (39.1%) under ADA treatment.

Under the assessment of the treating physician, the doses of 26 of all 54 IFX therapies (48.1%; no sufficient information on dose escalation in one patient) were escalated after a median treatment duration of 5 mo (range: 1-26 mo), and in 17 of all 37 ADA therapies (45.9%) after a median treatment duration of 4 mo (range: 1-12 mo).

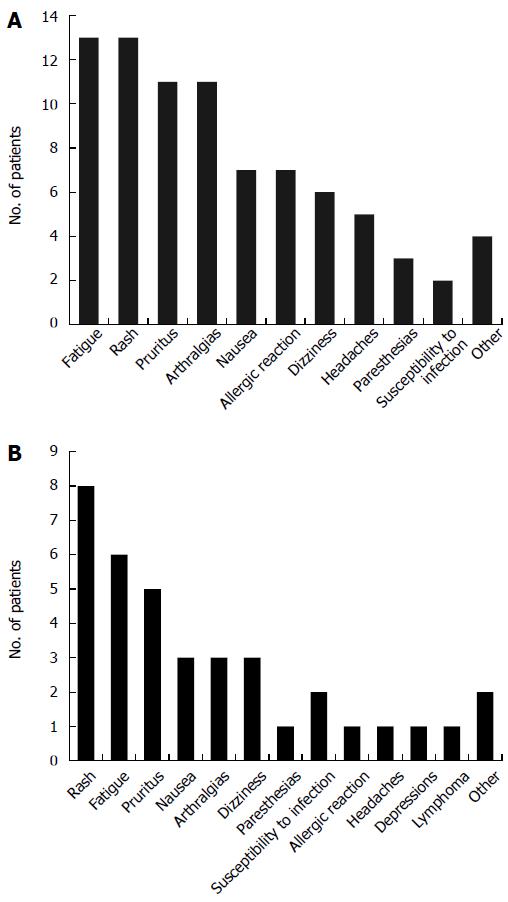

Among 55 patients who underwent therapy with IFX, 39 patients (70.9%) reported at least one side effect during the treatment. The most frequently observed side effects were fatigue (reported in 23.6%), a rash (reported in 23.6%), pruritus (20%), and arthralgias which had not been present before start of therapy (20%). One patient developed acute bullous dermatosis (linear IgA dermatosis) after his third IFX infusion, and one patient without previous neurological disease suffered an epileptic seizure after his first IFX infusion. Finally, one patient experienced Varizella Zoster Virus (VZV) reactivation under IFX therapy. Side effects under IFX treatment may be viewed in Figure 2A. Ten patients (18.2%) had to discontinue IFX treatment under the advice of the treating physician due to severe side effects (Table 4 for individual reasons). Among 37 ADA-treated patients (partly overlapping with the IFX-treated group), 25 (67.6%) developed at least one relevant adverse event (Figure 2B). The most frequently reported side effect was a rash (21.6%). All side effects may be viewed in Figure 2B. Five patients (13.5%) had to discontinue ADA therapy due to adverse events (Table 4 for individual reasons).

| Adverse events necessitating discontinuation of infliximab therapy |

| Severe non-preexisting arthralgia with high anti-IFX antibody titer |

| IFX-induced linear IgA dermatosis after 3rd infusion |

| Epileptic seizure (first event) directly after start of 1st infusion |

| IFX-induced hepatitis |

| Severe non-preexisting arthralgia |

| Severe anaphylactic reaction |

| Severe anaphylactic reaction |

| Allergic reaction after 19 mo of therapy |

| Severe non-preexistent myalgia and arthralgia |

| Severe anaphylactic reaction |

| Adverse events necessitating discontinuation of adalimumab therapy |

| Generalized pruritus and exanthema, classified as allergic reaction |

| ADA-induced hepatitis |

| Acute absceding pyelonephritis |

| EBV-associated B-cell Hodgkin lymphoma, nodular-sclerosing type, stadium IIIB1 |

| Frequent infections, especially of the upper respiratory tract |

Among the 72 patients in this study, 20 received both IFX and ADA consecutively; 15 were on IFX first, and five were on ADA first. Nine patients changed the anti-TNFα agent due to primary non-response, while four switched agents after a secondary loss of response and six due to side effects induced by the first TNFα inhibitor they used. One patient stopped IFX therapy as he had attained remission, and started ADA treatment after an interval of no anti-TNFα therapy. Three of six patients who switched due to side effects experienced allergic reactions to IFX, two switched due to IFX-induced arthralgia, and one switched from ADA to IFX due to ADA-induced hepatitis. Two of the six patients who switched therapy due to side effects achieved remission on the second anti-TNFα antibody, while none of the 13 patients who had switched the TNFα antibody for non-response or secondary loss of response achieved remission on the second antibody. This means that the group switching due to side effects reached remission significantly more often than the group switching due to non-response or secondary loss of response (P = 0.028).

Although a considerable number of UC patients are currently treated with TNFα inhibitors, the number of published reports on real-life experience using anti-TNFα agents to treat UC is relatively low[10,11,15-19].

Our study suggests that the clinical outcome of anti-TNFα treatment for UC in a real-life setting at a tertiary referral center is rather disappointing. However, interpretation of our results should take into consideration that patients transferred to a tertiary referral center usually suffer from refractory colitis that was not manageable using corticosteroid or immunomodulator treatment. As a matter of course, clinical trials also include individuals with refractory disease, but they carry the bias of strict inclusion criteria and select patients who are more likely to be motivated and compliant.

The rate of steroid-free clinical remission under anti-TNFα treatment in this real-life study was only 22.2%. Comparing our results with those of RCTs is difficult, as definitions and time points vary greatly in different studies. In the ACT study by Rutgeerts et al[6] the clinical remission rate at week 54 of IFX treatment was 34.7%, and in the ULTRA-2 study, the one year remission rate of ADA-treated patients was 22%[20]. Our rate of overall steroid-free clinical remission under anti-TNFα therapy is comparable to the latter.

Our data stand in sharp contrast to data from an otherwise comparable real-life observational study from Canada that included 53 UC patients[17]. Responses to induction therapy were 96.4% for IFX and 80% for ADA (P = 0.089). However, these data cannot be readily compared with ours, as our end point of steroid-free clinical remission was more rigorous than an end point of response. Yet, in our study, the overall reduction of the number of bowel movements, bloody stools and biochemical parameters of inflammation under anti-TNFα treatment was remarkably poor. However, our results should not be interpreted too negatively, as most of the patients who achieved remission had a clear benefit from the treatment with remission times up to 69 mo.

Another objective of our study was to examine whether there are potential factors influencing the response to anti-TNFα therapy in UC patients. It has been shown previously that outcomes under anti-TNFα therapy may be more favorable in patients with no prior use of immunosuppressants[10]. In our study, with steroid-free clinical remission as the primary end point, we could not confirm this relationship. Surprisingly, we found that patients with lower hemoglobin and serum albumin concentrations at the start of treatment had a greater chance of achieving steroid-free clinical remission than those with higher concentrations. These results are in contrast to those of Oussalah et al[18] who found that one of the predictors for primary non-response to anti-TNFα in UC was a hemoglobin level of less than 9.4 g/dL before treatment. It seems logical that anti-TNFα therapy might be more successful in patients with more severe inflammation, thus expressing more anti-TNFα in their intestinal mucosa, but patients with very low hemoglobin levels might have too severe disease to respond to therapy. It is also known that very low levels of plasma albumin can impair the efficacy of anti-TNFα treatment[21], yet our ambulatory patients did not display very low albumin concentrations.

In the period of this study, 20.8% of our patients required colectomy because of non-response to therapy. In the literature, colectomy rates for UC vary between 9% and 35% and thus correspond to our numbers[6]. However, the colectomy rate might not be a reliable outcome parameter in our study, as patients whose therapies failed sometimes changed to a different center or doctor or alternative treatment to avoid surgery. These patients were lost to our follow-up. This is why real colectomy rates may be higher than the ones found in this study.

Another important result of this study is that, in our cohort, no patient who switched from one TNFα antagonist to the other for primary non-response or loss of efficacy had a therapeutic benefit from the second TNFα inhibitor.

In our cohort, adverse events under anti-TNFα therapy were frequent (in 70.9% of IFX-treated patients and 67.6% of ADA-treated patients). Comparable numbers have been reported in large RCTs. In the ACT study, 87.6% of the patients treated with an IFX dose of 5 mg/kg body weight and 91% of the patients treated with a dose of 10 mg/kg body weight developed side effects[6]. In the ULTRA-1 study, about 50% of the patients treated with ADA experienced side effects[7]. As expected, due to the higher immunogenicity of IFX as compared with ADA, allergic reactions were observed more often in IFX-treated patients than in ADA-treated patients.

In our study, 18.2% of the IFX-treated patients and 13.5% of the ADA-treated patients had to discontinue their therapy due to severe side effects. This difference between the two medications may be explained by the relatively high number of severe allergic reactions - often manifesting as anaphylaxis - in the IFX-treated group.

There are several interesting individual findings in this study concerning potential anti-TNFα side effects. One of our male patients developed drug-induced linear IgA dermatosis with a clear temporal relationship to IFX therapy. After discontinuation of treatment, the disease only healed using high doses of steroids plus diamino-diphenyl sulfone (dapsone) for a long time period. To our knowledge, this is the first report on such a case in the literature. In addition, there was one case of a very young male who developed EBV-positive B cell Hodgkin lymphoma while under ADA treatment after consecutive therapies with AZA and IFX. The effect of immunosuppressive drugs on the risk of lymphoma remains a matter of debate[22]. Data from patients with rheumatoid arthritis suggest an increased incidence of malignancy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with TNFα antibodies, with a disproportionate representation by lymphoma, but mainly Non-Hodgkin lymphoma[23]. Some authors suggest that AZA therapy is more detrimental than anti-TNFα therapy regarding the development of malignancies and especially lymphomas[24,25]. In our case, it cannot be proven whether anti-TNFα therapy was responsible for the development of lymphoma, or whether AZA, or the subsequent immunosuppressive therapy - or none of the treatments - were. Yet this case should remind us of this potential life-threatening complication when starting a patient on anti-TNFα therapy, especially if he or she is EBV positive.

Overall, IFX and ADA can be considered as effective treatment options for UC, but only in about a fifth of all patients. Those patients who achieve clinical remission mostly have a long-term benefit from the therapy. However, as remission rates are still low, patients should be made aware of the expected success rates and be offered alternative therapies, such as proctocolectomy. Furthermore, our data suggest that switching anti-TNFα agents for UC for lack of response is no viable option to improve response to therapy.

We would like to thank C. W. Gauss for the proof-reading. Parts of this manuscript appear in the doctoral thesis of E. Baki.

One of the therapeutic options for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis is anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNFα).

Therapeutic options for the treatment of patients with refractory ulcerative colitis are very limited, and in many cases do not meet the treatment goals set for the patients. Also, they often come along with partly severe side effects restricting their use even in cases of good efficacy. Yet efficacy data are also still overall disappointing.

Many novel medications to treat ulcerative colitis are recently released or still in the pipeline, and it is very important for the treating doctors to know as much as possible about expected response and discontinuation rates, especially in real-life settings, for the best of their patients.

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory condition of the colon with yet unknown etiology. TNFα inhibitors are monoclonal antibodies directed against tumor necrosis factor alpha, which is a cytokine involved in systemic inflammation, also playing a role in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis. TNFα inhibitors approved for the treatment of ulcerative colitis are infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab.

The present article deals with an important health problem: How to treat patients with ulcerative colitis? The purpose of the study was to determine to what extent treatment with anti-TNFα agents (infliximab and adalimumab) may lead to clinical remission of ulcerative colitis in patients (in a real-life setting). Real life remission rates were overall low. The results show that about one fifth of the 72 patients achieved remission. Although the data presented indicate that the real life remission rates of ulcerative colitis after treatment with anti-TNFα were low, the report gives, nevertheless, information that is very useful for further work in the field.

P- Reviewer: Berg T, Wu WJ S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541-1549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2987] [Cited by in RCA: 3055] [Article Influence: 132.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Lukas M, MacIntosh D, Panaccione R, Wolf D, Pollack P. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn’s disease: the CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:323-333; quiz 591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1153] [Cited by in RCA: 1194] [Article Influence: 62.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Lukas M, MacIntosh DG, Panaccione R, Wolf D, Kent JD, Bittle B. Adalimumab for maintenance treatment of Crohn’s disease: results of the CLASSIC II trial. Gut. 2007;56:1232-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 708] [Cited by in RCA: 771] [Article Influence: 42.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, Hanauer SB, Panaccione R, Schreiber S, Byczkowski D, Li J, Kent JD. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn’s disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:52-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1598] [Cited by in RCA: 1620] [Article Influence: 90.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, Chey WY, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Kamm MA, Korzenik JR, Lashner BA, Onken JE. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1581] [Cited by in RCA: 1553] [Article Influence: 74.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Travers S, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462-2476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2744] [Cited by in RCA: 2885] [Article Influence: 144.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Hommes DW, D’Haens G, Hanauer S, Schreiber S, Panaccione R, Fedorak RN, Tighe MB, Huang B. Adalimumab for induction of clinical remission in moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results of a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2011;60:780-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 588] [Cited by in RCA: 671] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano C, Zhang H, Strauss R, Johanns J, Adedokun OJ, Guzzo C, Colombel JF, Reinisch W. Subcutaneous golimumab induces clinical response and remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:85-95; quiz e14-e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 563] [Cited by in RCA: 683] [Article Influence: 62.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano C, Zhang H, Strauss R, Johanns J, Adedokun OJ, Guzzo C, Colombel JF, Reinisch W. Subcutaneous golimumab maintains clinical response in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:96-109.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 516] [Article Influence: 46.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Armuzzi A, Biancone L, Daperno M, Coli A, Pugliese D, Annese V, Aratari A, Ardizzone S, Balestrieri P, Bossa F. Adalimumab in active ulcerative colitis: a “real-life” observational study. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:738-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhou YL, Xie S, Wang P, Zhang T, Lin MY, Tan JS, Zhi FC, Jiang B, Chen Y. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in treating patients with ulcerative colitis: experiences from a single medical center in southern China. J Dig Dis. 2014;15:483-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Stidham RW, Lee TC, Higgins PD, Deshpande AR, Sussman DA, Singal AG, Elmunzer BJ, Saini SD, Vijan S, Waljee AK. Systematic review with network meta-analysis: the efficacy of anti-TNF agents for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:1349-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Stange EF, Travis SP, Vermeire S, Reinisch W, Geboes K, Barakauskiene A, Feakins R, Fléjou JF, Herfarth H, Hommes DW. European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis: Definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2008;2:1-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1970] [Cited by in RCA: 2349] [Article Influence: 123.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Ferrante M, Vermeire S, Fidder H, Schnitzler F, Noman M, Van Assche G, De Hertogh G, Hoffman I, D’Hoore A, Van Steen K. Long-term outcome after infliximab for refractory ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2008;2:219-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Afif W, Leighton JA, Hanauer SB, Loftus EV, Faubion WA, Pardi DS, Tremaine WJ, Kane SV, Bruining DH, Cohen RD. Open-label study of adalimumab in patients with ulcerative colitis including those with prior loss of response or intolerance to infliximab. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1302-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gies N, Kroeker KI, Wong K, Fedorak RN. Treatment of ulcerative colitis with adalimumab or infliximab: long-term follow-up of a single-centre cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:522-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Oussalah A, Laclotte C, Chevaux JB, Bensenane M, Babouri A, Serre AA, Boucekkine T, Roblin X, Bigard MA, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Long-term outcome of adalimumab therapy for ulcerative colitis with intolerance or lost response to infliximab: a single-centre experience. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:966-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Halpin SJ, Hamlin PJ, Greer DP, Warren L, Ford AC. Efficacy of infliximab in acute severe ulcerative colitis: a single-centre experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1091-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, D’Haens G, Wolf DC, Kron M, Tighe MB, Lazar A, Thakkar RB. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:257-265.e1-e3. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Fasanmade AA, Adedokun OJ, Olson A, Strauss R, Davis HM. Serum albumin concentration: a predictive factor of infliximab pharmacokinetics and clinical response in patients with ulcerative colitis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;48:297-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mariette X, Tubach F, Bagheri H, Bardet M, Berthelot JM, Gaudin P, Heresbach D, Martin A, Schaeverbeke T, Salmon D. Lymphoma in patients treated with anti-TNF: results of the 3-year prospective French RATIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:400-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, Buchan I, Matteson EL, Montori V. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006;295:2275-2285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1816] [Cited by in RCA: 1813] [Article Influence: 95.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kotlyar DS, Lewis JD, Beaugerie L, Tierney A, Brensinger CM, Gisbert JP, Loftus EV Jr, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Blonski WC, Van Domselaar M. Risk of Lymphoma in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treated With Azathioprine and 6-Mercaptopurine: A Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Khan N, Abbas AM, Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Bazzano LA. Risk of lymphoma in patients with ulcerative colitis treated with thiopurines: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1007-1015.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |