Published online Jan 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.276

Peer-review started: March 27, 2014

First decision: May 29, 2014

Revised: June 7, 2014

Accepted: July 15, 2014

Article in press: July 16, 2014

Published online: January 7, 2015

Processing time: 286 Days and 19.6 Hours

AIM: To determine the risk factors for gallstone-related biliary events.

METHODS: This retrospective cohort study evaluated magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography images from 141 symptomatic and 39 asymptomatic gallstone patients who presented at a single tertiary hospital between January 2005 and December 2012.

RESULTS: Logistic regression analysis showed significant differences between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with gallstones in relation to the number of gallstones, the angle between the long axis of the gallbladder and the cystic duct, and the cystic duct diameter. Multivariate analysis showed that the number of gallstones (OR = 1.27, 95%CI: 1.03-1.57; P = 0.026), the angle between the long axis of the gallbladder and the cystic duct (OR = 1.02, 95%CI: 1.00-1.03; P = 0.015), and the diameter of the cystic duct (OR = 0.819, 95%CI: 0.69-0.97; P = 0.018) were significantly associated with biliary events. The incidence of biliary events was significantly elevated in patients who had the presence of more than two gallstones, an angle of > 92° between the gallbladder and the cystic duct, and a cystic duct diameter < 6 mm.

CONCLUSION: These findings will help guide the treatment of patients with asymptomatic gallstones. Clinicians should closely monitor patients with asymptomatic gallstones who exhibit these characteristics.

Core tip: This is a retrospective cohort study that evaluated magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography images from 180 patients. We found that the incidence of biliary events was significantly elevated in patients who had more than two gallstones, an angle of > 92° between the gallbladder and the cystic duct, and/or a cystic duct diameter < 6 mm. When considering these factors as a risk factor of gallstone-related biliary events, the positive predictive value for biliary events in patients with all three risk factors was 89.3%.

- Citation: Park JS, Lee DH, Lim JH, Jeong S, Jeon YS. Morphologic factors of biliary trees are associated with gallstone-related biliary events. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(1): 276-282

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i1/276.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.276

Gallstone disease is a common reason for abdominal pain, leading to significant morbidity, mortality, and considerable health care costs. The prevalence of gallstones in the adult population is estimated to be between 10%-15% in Western countries, including over 20 million people in the United States[1]. In Korea, 3.1% of men and 3.4% of women have gallstones[2]. Gallstones are often discovered incidentally during the ultrasound investigations that form part of regular health assessments, and over 70% of gallstones are asymptomatic[3]. In patients with asymptomatic gallstones, 10% will experience a gallstone-related biliary event, including biliary colic, acute cholecystitis, acute cholangitis, or acute pancreatitis, within five years of diagnosis, and 20% will experience a gallstone-related biliary event within 20 years of diagnosis[3,4]. Therefore, investigating the risk factors associated with biliary events in patients with asymptomatic gallstones is important for determining which patients should be treated, and to prevent unnecessary treatment of gallstones[5-7].

The risk factors associated with gallstone-related biliary events include small and multiple gallstones, gallbladder dysfunction, being female, having a family history of gallstones, and pregnancy; the risk factors that can predict the occurrence of biliary events have not yet been satisfactorily defined[8,9]. The generally accepted cause of gallstone-related biliary events is an impacted gallstone in the cystic duct, neck of the gallbladder, or bile duct[10]. Thus, the morphologic characteristics of the gallbladder and cystic duct are likely to be important factors underlying biliary events, but there have been no studies thoroughly evaluating this. We hypothesized that the angle between the long axis of the gallbladder and the cystic duct, the diameter of the cystic duct, and/or gallstone characteristics are associated with biliary events. Therefore, we conducted a study using magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) to determine whether the morphologic characteristics of the gallbladder and the cystic duct and the number of gallstones are risk factors for biliary events. We also attempted to quantitatively evaluate the relationship between these risk factors and gallstone-related biliary events.

This retrospective case-control study was performed at the Inha University Hospital, Incheon, South Korea. The patients who enrolled in the study underwent MRCP and had gallstones, and were classified into two groups based on whether or not they had experienced biliary events. The characteristics of the MRCP images were compared between the two groups. This study was approved by the hospital’s institutional review board (IUH-IRB 13-2823).

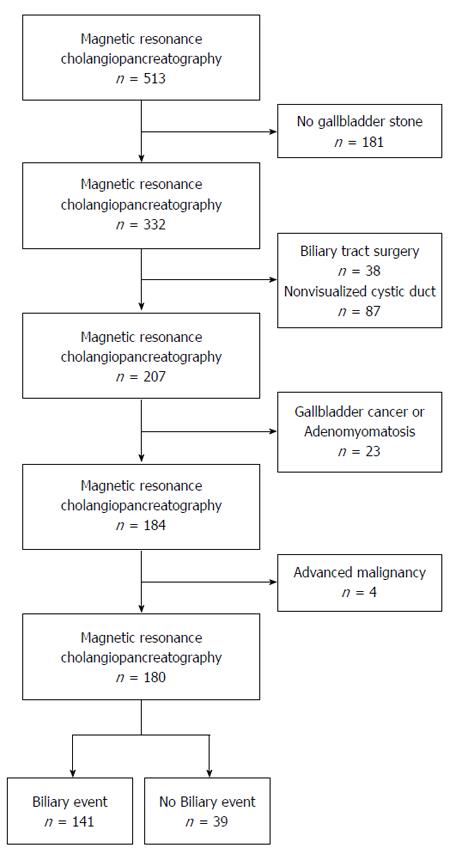

We studied patients who underwent MRCP between January 2005 and December 2012. The study’s inclusion criteria were that the patients were ≥ 20 years-old and that they had gallstones. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) a history of biliary tract surgery; (2) the cystic duct not being visualized on the MRCP images; (3) the presence of abnormal anatomy of the biliary tree caused by gallbladder cancer or adenomyomatosis; and (4) having other reasons for abdominal pain. The patients’ medical records were reviewed and the clinical characteristics and course were extracted along with the MRCP findings. Gallstone-related biliary events were defined as biliary colic, cholangitis, acute cholecystitis and acute biliary pancreatitis. Biliary colic was defined as recurrent pain in the epigastrium or right upper quadrant that lasted longer than 15-30 min that was not relieved by bowel movements, postural changes, or antacids, and was eventually relieved by cholecystectomy[11]. The Tokyo Guidelines[12] were used to diagnose cholangitis and cholecystitis, which was confirmed by MRCP findings showing a pericholecystic high signal, an enlarged gallbladder, and a thickened gallbladder wall[13].

MR imaging was performed on patients after an overnight fast (≥ 8 h) using 1.5 T MR scanners (Signa EXCITE and Signa HDxt; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). Axial T1-weighted gradient echo images [repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE): 135/4.3 ms, flip angle: 60°, slice thickness: 5 mm], axial T2-weighted spin-echo images (TR/TE: 1500/86.8 ms, flip angle: 90°, slice thickness: 5 mm), coronal T2-weighted spin-echo images (TR/TE: 1500/86.8 ms, flip angle: 90°, slice thickness: 5 mm), and thick-slab MRCP (TR/TE: 4000/900 ms, flip angle: 90°, slice thickness: 40 mm) were acquired. No contrast media were used. The MRCP images were interpreted by a single radiologist who had over five years of experience interpreting gastroenterologic images and who measured the parameters in the MRCP images without any knowledge of the patients’ clinical information.

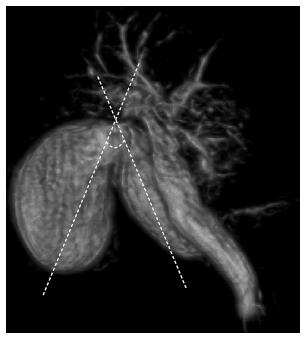

The angle formed by the long axis between the gallbladder and the cystic duct was evaluated. The most acute angle was measured on the three-dimensional MRCP images at the intersection between two virtual lines, one that extended along the cystic duct, and the long axis of the gallbladder, which was the virtual line connecting the fundus to the neck of the gallbladder (Figure 1). The diameter of the cystic duct was measured at the widest part of the entire duct. Gallstone size was defined as the size of the largest stone.

We hypothesized that more biliary events induced by gallstones will occur as the angle between the long axis of the gallbladder and the cystic duct approaches 180°, because as the angle widens, it becomes easier for the gallstones to enter and impact the cystic duct. And we also hypothesized that a small cystic duct diameter would cause biliary events because of the potential of gallstone impaction in the cystic duct as they move along it after passing through the orifice.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 19.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). The baseline characteristics were compared using an independent t-test for continuous variables and a χ2 test for categorical variables. In the preliminary analysis, univariate logistic regression was used to determine whether particular factors influenced the incidence of gallstone-related biliary events. Multivariate logistic regression analysis tested the outcomes from the univariate logistic regression analysis. The OR and 95%CI are presented. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to determine the cut-off values for the number of gallstones, the angle between the gallbladder and the cystic duct, and the cystic duct diameter that had the highest sensitivities and specificities, and these were used to classify patients based on the presence or absence of biliary symptoms. The χ2 test was used to compare the incidence of biliary events between the groups that were classified according to the cut-off values. Data are presented as mean ± SD, and a P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

The medical records of 513 patients aged 20 years or older who underwent MRCP were reviewed; 333 patients were excluded from the study. Among the patients who were excluded, 38 had undergone cholecystectomy, 181 did not have gallstones, 87 had cystic ducts that could not be visualized on the MRCP images, 23 had abnormal gallbladder anatomies caused by gallbladder cancer or adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder, and 4 patients had advanced malignancies and abdominal pain that could be confused with biliary colic. A total of 180 patients with gallstones confirmed by MRCP were enrolled in the study (Figure 2). The case Group A was comprised of 141 of these patients who had gallstones and had experienced biliary events, including biliary colic (n = 67), cholangitis (n = 16), and acute cholecystitis (n = 58), with no cases of acute biliary pancreatitis. The 39 patients without biliary events served as controls in Group B, including individuals who had undergone MRCP for the detection of concealed malignancy (n = 20), those with other benign disease (n = 10), those with small hepatocellular carcinomas (n = 5), and those with small cholangiocarcinomas (n = 4). MRCP did not reveal any abnormalities in the structures of the gallbladder or the cystic duct in the control group.

No statistically significant differences were observed between Group A and Group B in relation to the baseline clinical characteristics, which included age, sex, the presence of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, body mass index, and the hemoglobin and total cholesterol levels. Logistic regression analysis showed significant differences between the groups in the number of gallstones, the angle between the gallbladder and the cystic duct, and the cystic duct diameter (Ps < 0.05) (Table 1). A multivariate analysis also showed that there were statistically significant differences in these factors between Group A and Group B (Table 2). Consequently, we determined that the number of gallstones, the angle between the gallbladder and the cystic duct, and the cystic duct diameter were relative risk factors associated with biliary events, and we explored these factors further.

| Factor | Group A (n = 141) | Group B (n = 39) | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value |

| Age, yr | 67.2 ± 12.9 | 65.2 ± 15.1 | 0.99 | 0.97-1.02 | 0.46 |

| Male/female, n | 77/64 | 17/22 | 1.56 | 0.76-3.18 | 0.22 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n | 41 | 10 | 1.15 | 0.51-0.58 | 0.74 |

| Hypertension, n | 54 | 14 | 1.06 | 0.51-2.23 | 0.87 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.7 ± 5.9 | 21.6 ± 7.14 | 1.03 | 0.97-1.08 | 0.37 |

| Hemoglobin, mg/dL | 13.1 ± 2.1 | 12.6 ± 1.8 | 1.13 | 0.95-1.34 | 0.18 |

| Total cholesterol | 174.2 ± 52.7 | 177.2 ± 60.5 | 0.99 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.77 |

| Gallstone size, mm | 9.5 ± 7.3 | 8.4 ± 3.4 | 1.35 | 0.76-2.40 | 0.31 |

| Gallbladder/cystic duct angle | 113.7°± 28.6° | 98.1°± 36.2° | 1.02 | 1.01-1.03 | < 0.01 |

| Number of gallstones | 3.6 ± 1.9 | 2.8 ± 2.0 | 1.23 | 1.02-1.47 | 0.03 |

| Cystic duct diameter, mm | 5.9 ± 1.9 | 6.9 ± 3.4 | 0.86 | 0.74-0.98 | 0.03 |

| Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value | |

| Numbers of stones | 1.32 | 1.08-1.62 | < 0.01 |

| Angle | 1.02 | 1.01-1.03 | 0.02 |

| Cystic duct diameter | 0.83 | 0.71-0.97 | < 0.01 |

The mean number of gallstones was 3.6 ± 1.9 and 2.8 ± 2.0 for Group A and Group B, respectively. Logistic regression analysis showed that patients who had experienced biliary events tended to have more gallstones than patients who had not experienced biliary events (OR = 1.32, 95%CI: 1.08-1.62; P < 0.01). A cut-off value of two gallstones, determined from the ROC curve analysis, was used to analyze the impact of the number of gallstones on the incidence of biliary-related events. χ2 analysis showed that biliary events occurred more often when patients had more than two gallstones (OR = 2.30, 95%CI: 1.12-4.74; P = 0.02).

The mean angle between the long axis of the gallbladder and the cystic duct was 113.7°± 28.6° and 98.1°± 36.2° in Group A and Group B, respectively, which was significantly different (P < 0.01). More biliary events were associated with a wider angle between the gallbladder and the cystic duct. Logistic regression analysis showed that the odds of experiencing a biliary event increased by 1.02 with a 1° increase in the angle (95%CI: 1.01-1.03; P = 0.02). The occurrence of biliary events increased significantly in patients with angles that were > 92° (OR = 2.28, 95%CI: 1.08-4.81; P = 0.03).

Univariate analysis showed a significant difference between Group A and Group B in the diameter of the cystic duct (5.9 ± 1.9 mm vs 6.9 ± 3.4 mm, P = 0.03). Results from the multivariate analysis showed that the odds of a biliary event were reduced by 0.83 if the cystic duct diameter increased by 1 mm (95%CI: 0.71-0.97; P < 0.01). Using a cut-off value determined from ROC curve analysis, we classified the patients based on whether the diameters of their cystic ducts were < 6 mm or ≥ 6 mm, and we compared the incidence of biliary events. Although we did not obtain statistically significant results, the occurrence of biliary events was somewhat more frequent in patients with a smaller cystic duct diameter (OR = 0.50, 95%CI: 0.23-1.09; P = 0.08).

In this study, 28 patients had all three relative risk factors, and among these, a biliary event occurred in 25 patients. Hence, the positive predictive value for biliary events in patients with all three risk factors was 89.3%. In contrast, of the 39 patients who did not experience biliary events, only 3 had all three relative risk factors.

Cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallstones is regarded as a very safe surgical procedure, with a mortality rate of only 0.2%-0.5%[14]. Despite this, it is difficult to recommend prophylactic cholecystectomy for patients with asymptomatic gallstones when its cost-effectiveness and the possibility of complications are taken into consideration. Nevertheless, treating patients conservatively until they become symptomatic is not always the correct approach when the potential for the development of serious complications is considered, especially in elderly patients[15]. Therefore, it is important to identify factors that can increase the risk of conversion to a symptomatic gallstone disease or for developing complications. Numerous long-term studies have indicated that the progression from asymptomatic to symptomatic gallstone disease is associated with being < 55 years of age, a smoker, female, having a high body weight, having three or more gallstones, and having floating stones[16,17]. Other identified risk factors include calculi < 3 mm in diameter, a patent cystic duct, a non-functioning gallbladder, and perioperative detection of incidental stones[8,18]. In the current study, we analyzed the correlation between biliary events and risk factors that are related to symptomatic gallstone disease, including sex, age, body mass index, size of the calculi, diabetes mellitus, and total cholesterol levels, and most of these factors were not related to gallstone-related biliary events. Factors revealed as being related to biliary events included the cystic duct diameter, the number of gallstones, and the angle between the gallbladder and the cystic duct.

Limited studies have investigated the association between the cystic duct diameter and biliary events. Most of the studies examining cystic duct diameters have been conducted in patients with acute biliary pancreatitis[19,20]. Sugiyama et al[19] determined that an enlarged cystic duct (≥ 5 mm) was an important factor predisposing patients to acute biliary pancreatitis. The authors suggested that pancreatitis occurs more often in enlarged cystic ducts because gallstones are more likely to pass through a wider cystic duct. Reports from other studies have also presented similar results and proposed similar mechanisms[21-23]. However, in the current study, smaller cystic duct diameters were associated with the occurrence of gallstone-related biliary events. Although the previous reports did not describe their measurement methods in detail, it is likely that the diameters of the cystic ducts were measured at the entrance in order to suggest that gallstones may induce biliary pancreatitis. In contrast, we measured the diameter of the cystic duct at the widest part of the duct. Therefore, assuming that the gallstones pass through the entrance, our observations concur with the risk for impaction as they move along the cystic duct. In fact, the normal diameter of the cystic duct varies from 1-5 mm[24]. In this study, the mean cystic duct diameter was 6.1 ± 2.36 mm, which is slightly wider than the average documented cystic duct diameter. We suspect that this could be attributed to motion artifacts caused by respiration during MRCP; hence, the cystic ducts evaluated were slightly larger than the actual size. However, we believe that this artifact did not significantly influence the association between a smaller cystic duct and the incidence of biliary events.

In the current study, the number of gallstones was correlated with biliary events, which is consistent with previous reports. For example, Ros et al[25] used cholecystosonography and cholecystography to compare the number of gallstones with associated symptoms in a series of 260 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed, uncomplicated gallstone disease, of whom 146 had experienced biliary pain and 114 were asymptomatic. Their results showed multiple gallstones were significantly associated with the occurrence of biliary symptoms. Sohail et al[26] also showed that the number of calculi is an important factor in the occurrence of biliary symptoms and the selection of management options. In comparison with previous papers, our results can be used to establish standards for distinguishing patients requiring treatment from those with asymptomatic gallstones. In our study, biliary events were more than twice as likely in patients with more than two gallstones. This finding will help in determining treatment methods or in predicting the occurrence of biliary events in patients with asymptomatic gallstones.

To the best of our knowledge, no research has been conducted on the correlation between the angle formed by the long axis of the gallbladder and the cystic duct and biliary symptoms. However, this study was not the first attempt to measure this angle. Indeed, Deenitchin et al[27] first reported on the measurement of this angle in a study investigating the association between complex cystic ducts and cholelithiasis using cholangiography. They reported that a more acute angle contributed to lithogenesis. The results from our study show that a wider angle is associated with a higher occurrence of biliary events. We suggest that as the angle approaches 180°, it may facilitate the entrance of calculi into the cystic duct because of a reduced resistance from a wider angle. However, given that our study is the first to evaluate the influence of this angle on gallstone-related biliary events, more studies are required to support this hypothesis.

Our study has several important clinical implications. This is the first study that has attempted to determine how anatomic factors associated with the gallbladder and cystic duct affect the generation of biliary events, and it is critical that these factors are analyzed to substantiate the mechanisms underlying biliary colic or cholecystitis. Furthermore, the results from our study have generated data that can be used to predict gallstone-related biliary events before they occur in patients with asymptomatic gallstones. The positive predictive value for biliary events in patients with all three risk factors (more than two gallstones, a cystic duct diameter < 6 mm in MRCP images, and an angle of > 92° between the gallbladder and the cystic duct) was 89.3%. While this finding may not provide a clear standard of care for patients with asymptomatic gallstones, we believe that these factors contributed to the occurrence of biliary events, indicated that asymptomatic gallstones should be treated prophylactically.

This study has several limitations. First, the shape of the gallbladder and the angle between gallbladder and cystic duct may change in relation to a patient’s posture or after eating and we suspect that these factors may affect the occurrence of biliary events. However, we were unable to evaluate this given that the MRCPs were carried out with the patients in the supine position and in a fasted state. Therefore, other MRCP techniques or another form of radiologic examination is needed to successfully evaluate the relationship between biliary events and these factors. The second limitation of this study relates to the resolution of the MRCP images for the evaluation of the cystic ducts. Although MRCP is a non-invasive imaging method with an accuracy rate that matches that of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in pancreatobiliary disease[28] and is frequently used in the visualization of the cystic duct[29], its low resolution prohibits the visualization of minor ducts in the biliary tree[30]. Using the same non-contrast MRCP technique that was used in the present study, cystic ducts were detected in 126/171 (74%) patients reported by Taourel et al[31], and in 24 (77.5%) patients studied by Mutlu et al[32]. The cystic duct was not visualized in 87 of the patients in our study, which may have been due to selection bias. We expect that enhanced MRCP techniques would have produced more accurate results in this study because this technique can improve the visualization of the cystic duct[29]. A third limitation of this study was the case volume. The number of patients in the control group was smaller than in the case group, which may have limited the accuracy of the results. However, as this was a retrospective study, there were a few patients that had a normal biliary tree. Therefore, a large-scale prospective study is needed to more definitively estimate the risk factors.

In conclusion, the number of gallstones, the angle between the long axis of the gallbladder and the cystic duct, and the diameter of the cystic duct are significantly related to gallstone-related biliary events. We suggest that clinicians should closely monitor patients with asymptomatic gallstones who have these relative risk factors, particularly those with multiple gallstones, a large angle formed between the long axis of the gallbladder and the cystic duct, and a narrow cystic duct.

All of the authors certify that neither this manuscript nor a manuscript with substantially similar content under their authorship has been published or is being considered for publication elsewhere. All of the authors disclose that there are no conflicts of interest.

One of the most important and challenging tasks involving gallstone-related biliary events is to determine which patients should receive gallstone treatment. Although there are a few studies to suggest risk factors, those that can predict the occurrence of biliary events have not yet been satisfactorily defined. In addition, there have been no studies concerning the relation between biliary anatomic factors and biliary events.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is a valuable technique to evaluate morphologic factors of the biliary system. Recent advances in scanner technology have allowed faster image acquisition and better quality with MRCP, thus providing more detailed images for evaluation of the biliary system.

The current study shows that the number of gallstones, the angle between the long axis of the gallbladder and the cystic duct, and the diameter of the cystic duct are significantly related to gallstone-related biliary events. Particularly, the incidence of biliary events was significantly elevated in patients who had more than two gallstones, an angle of > 92° between the gallbladder and the cystic duct, and a cystic duct diameter < 6 mm.

Clinicians should closely monitor patients with asymptomatic gallstones who have relative risk factors, particularly those with multiple gallstones, a large angle formed between the long axis of the gallbladder and the cystic duct, and a narrow cystic duct.

Relative risk factors were defined as having more than two gallstones, a cystic duct diameter < 6 mm in MRCP images, and an angle of > 92° between the long axis of the gallbladder and the cystic duct.

This is a good retrospective study in which the authors analyzed the morphologic risk factors of gallstone-related biliary events using MRCP. The results show the number of gallstones, the angle between the long axis of the gallbladder and the cystic duct, and the diameter of the cystic duct are significantly related to gallstone-related biliary events.

P- Reviewer: Corrales FJ, Crenn PP, Ocker M, Weng HL S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: AmEditor E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Schirmer BD, Winters KL, Edlich RF. Cholelithiasis and cholecystitis. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2005;15:329-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Kim WH, Lee KJ, Yoo BM, Kim JH, Kim MW. Relation between the risk of gallstone pancreatitis and characteristics of gallstone in Korea. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:343-345. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Portincasa P, Moschetta A, Petruzzelli M, Palasciano G, Di Ciaula A, Pezzolla A. Gallstone disease: Symptoms and diagnosis of gallbladder stones. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:1017-1029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Halldestam I, Enell EL, Kullman E, Borch K. Development of symptoms and complications in individuals with asymptomatic gallstones. Br J Surg. 2004;91:734-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chwistek M, Roberts I, Amoateng-Adjepong Y. Gallstone pancreatitis: a community teaching hospital experience. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:41-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Halvorsen FA, Ritland S. Acute pancreatitis in Buskerud County, Norway. Incidence and etiology. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:411-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Persson GE. Expectant management of patients with gallbladder stones diagnosed at planned investigation. A prospective 5- to 7-year follow-up study of 153 patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:191-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sakorafas GH, Milingos D, Peros G. Asymptomatic cholelithiasis: is cholecystectomy really needed? A critical reappraisal 15 years after the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1313-1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Friedman GD. Natural history of asymptomatic and symptomatic gallstones. Am J Surg. 1993;165:399-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Attili AF, De Santis A, Capri R, Repice AM, Maselli S. The natural history of gallstones: the GREPCO experience. The GREPCO Group. Hepatology. 1995;21:655-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Festi D, Reggiani ML, Attili AF, Loria P, Pazzi P, Scaioli E, Capodicasa S, Romano F, Roda E, Colecchia A. Natural history of gallstone disease: Expectant management or active treatment? Results from a population-based cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:719-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fujii Y, Ohuchida J, Chijiiwa K, Yano K, Imamura N, Nagano M, Hiyoshi M, Otani K, Kai M, Kondo K. Verification of Tokyo Guidelines for diagnosis and management of acute cholangitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:487-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yokoe M, Takada T, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, Hasegawa H, Norimizu S, Hayashi K, Umemura S, Orito E. Accuracy of the Tokyo Guidelines for the diagnosis of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis taking into consideration the clinical practice pattern in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:250-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rao A, Polanco A, Qiu S, Kim J, Chin EH, Divino CM, Nguyen SQ. Safety of outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the elderly: analysis of 15,248 patients using the NSQIP database. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:1038-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Behari A, Kapoor VK. Asymptomatic Gallstones (AsGS) - To Treat or Not to? Indian J Surg. 2012;74:4-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Friedman GD, Raviola CA, Fireman B. Prognosis of gallstones with mild or no symptoms: 25 years of follow-up in a health maintenance organization. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42:127-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Thistle JL, Cleary PA, Lachin JM, Tyor MP, Hersh T. The natural history of cholelithiasis: the National Cooperative Gallstone Study. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:171-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 18. | Patiño JF, Quintero GA. Asymptomatic cholelithiasis revisited. World J Surg. 1998;22:1119-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Risk factors for acute biliary pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:210-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | McMahon MJ, Shefta JR. Physical characteristics of gallstones and the calibre of the cystic duct in patients with acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1980;67:6-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Armstrong CP, Taylor TV, Jeacock J, Lucas S. The biliary tract in patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1985;72:551-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kelly TR. Gallstone pancreatitis. Local predisposing factors. Ann Surg. 1984;200:479-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Brink JA, Simeone JF, Mueller PR, Richter JM, Prien EL, Ferrucci JT. Physical characteristics of gallstones removed at cholecystectomy: implications for extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151:927-931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Turner MA, Fulcher AS. The cystic duct: normal anatomy and disease processes. Radiographics. 2001;21:3-22; questionnaire 288-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ros E, Valderrama R, Bru C, Bianchi L, Terés J. Symptomatic versus silent gallstones. Radiographic features and eligibility for nonsurgical treatment. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:1697-1703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sohail S, Iqbal Z. Sonographically determined clues to the symptomatic or silent cholelithiasis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2007;17:654-657. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Deenitchin GP, Yoshida J, Chijiiwa K, Tanaka M. Complex cystic duct is associated with cholelithiasis. HPB Surg. 1998;11:33-37. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Onder H, Ozdemir MS, Tekbaş G, Ekici F, Gümüş H, Bilici A. 3-T MRI of the biliary tract variations. Surg Radiol Anat. 2013;35:161-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Itatani R, Namimoto T, Kajihara H, Yoshimura A, Katahira K, Nasu J, Matsushita I, Sakamoto F, Kidoh M, Yamashita Y. Preoperative evaluation of the cystic duct for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: comparison of navigator-gated prospective acquisition correction- and conventional respiratory-triggered techniques at free-breathing 3D MR cholangiopancreatography. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:1911-1918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Düşünceli E, Erden A, Erden I. [Anatomic variations of the bile ducts: MRCP findings]. Tani Girisim Radyol. 2004;10:296-303. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Taourel P, Bret PM, Reinhold C, Barkun AN, Atri M. Anatomic variants of the biliary tree: diagnosis with MR cholangiopancreatography. Radiology. 1996;199:521-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mutlu H, Basekim CC, Silit E, Pekkafali Z, Erenoglu C, Kantarci M, Karsli AF, Kizilkaya E. Value of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiography in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2005;15:133-136; discussion 136-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |