Published online Dec 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i47.17955

Revised: July 23, 2014

Accepted: August 13, 2014

Published online: December 21, 2014

Processing time: 202 Days and 7.3 Hours

AIM: To retrospectively evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of interventional digital subtraction angiography (DSA) for bleeding small bowel gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs).

METHODS: Between January 2006 and December 2013, small bowel tumors in 25 consecutive patients undergoing emergency interventional DSA were histopathologically confirmed as GIST after surgical resection. The medical records of these patients and the effects of interventional DSA and the presentation and management of the condition were retrospectively reviewed.

RESULTS: Of the 25 patients with an age range from 34- to 70-year-old (mean: 54 ± 12 years), 8 were male and 17 were female. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, including tarry or bloody stool and intermittent melena, was observed in all cases, and one case also involved hematemesis. Nineteen patients required acute blood transfusion. There were a total of 28 small bowel tumors detected by DSA. Among these, 20 were located in the jejunum and 8 were located in the ileum. The DSA characteristics of the GISTs included a hypervascular mass of well-defined, homogeneous enhancement and early developed draining veins. One case involved a complication of intussusception of the small intestine that was discovered during surgery. No pseudoaneurysms, arteriovenous malformations or fistulae, or arterial rupture were observed. The completely excised size was approximately 1.20 to 5.50 cm (mean: 3.05 ± 1.25 cm) in maximum diameter based on measurements after the resection. There were ulcerations (n = 8), erosions (n = 10), hyperemia and edema (n = 10) on the intra-luminal side of the tumors. Eight tumors in patients with a large amount of blood loss were treated with transcatheter arterial embolization with gelfoam particles during interventional DSA.

CONCLUSION: Emergency interventional DSA is a useful imaging option for locating and diagnosing small bowel GISTs in patients with bleeding, and is an effective treatment modality.

Core tip: This study sample is the largest of its kind, and this article includes a detailed report on the patients with small bowel gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) based on digital subtraction angiography (DSA) visualization. The data indicate that an exact location can be determined and a diagnosis of the small bowel GISTs can be made even in patients undergoing emergency interventional DSA for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. For cases of severe anemia, these patients can also tolerate interventional DSA and management. Therefore, interventional DSA is an alternative effective imaging modality for locating and diagnosing small bowel GISTs, even in patients with bleeding.

- Citation: Chen YT, Sun HL, Luo JH, Ni JY, Chen D, Jiang XY, Zhou JX, Xu LF. Interventional digital subtraction angiography for small bowel gastrointestinal stromal tumors with bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(47): 17955-17961

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i47/17955.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i47.17955

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. They occur most commonly in the stomach, small intestine, large intestine and esophagus[1-3]. Although small bowel GISTs account for only 20% to 45% of GISTs, in recent years they have reportedly become more common and display more aggressive biobehaviors. Moreover, the recurrence rate of small bowel GISTs is higher than that of other tumors in the stomach or other sites[4-6]. Common symptoms of small bowel GISTs include abdominal pain, abdominal mass, GI bleeding and intestinal obstruction, but these cases are often nonspecific or asymptomatic, especially in cases involving smaller tumors[1-4,6]. The lack of specific clinical manifestations and the location of the tumors make the diagnosis difficult. Routine diagnostic imaging modalities mainly consist of endoscopic examination, computed tomography (CT) scanning, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)[7-12]. However, doctors who admit patients with acute or subacute obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) prefer to conduct emergency interventional digital subtraction angiography (DSA), whereas some routine exams are not able to identify the bleeding[13-15]. To our knowledge, few detailed reports on the use of interventional DSA for small bowel GISTs have been published to date.

In this study, 28 small bowel tumors in 25 consecutive patients undergoing interventional angiography were confirmed as GISTs based on histopathology after surgical resection. Patients’ medical data and the interventional DSA procedures were retrospectively analyzed, and the aim of the present study was to evaluate the diagnostic efficacy and the application of emergency interventional angiography for small bowel GISTs in patients with bleeding at Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital (Guangzhou, China).

From January 2006 to December 2013, 25 patients with acute or subacute OGIB as their main clinical manifestation were admitted to our department for emergency angiography examination to determine whether there were signs of active bleeding requiring further interventional treatment. We retrospectively studied these patients’ medical data and found 28 histopathologically confirmed GIST of the small intestine according to the DSA findings and location. The main clinical characteristics of the 25 patients are shown in Table 1. Before the DSA exam, the causes of bleeding in all of the patients were unclear based on routine endoscopy (gastric and colorectal endoscopes) and the following imaging modalities: abdominal ultrasound (n = 21), abdominal X-ray films (n = 16), abdominal CT plain scan (n = 7), and contrast-enhanced CT and CT angiography (n = 3). In one patient, a lower small intestine ileus was suspected based on abdominal X-ray, and a hypervascular mass in another patient was observed in the upper jejunum based on contrast-enhanced CT. However, enhanced CT did not facilitate a definite diagnosis of the mass as either hemangioma, vascular malformation or a small intestinal tumor by the radiological resident on duty. The review of the medical records was carried out with approval by the ethics committee of our hospital.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

| Age (yr) | |

| < 40 | 6 (24.0) |

| ≥ 40 | 19 (76.0) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 7 (28.0) |

| Female | 18 (72.0) |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | |

| > 90 | 5 (20.0) |

| 60-90 | 15 (60.0) |

| < 60 | 5 (20.0) |

| Symptoms | |

| Tarry or bloody stool | 25 (100) |

| Hematemesis | 1 (4.0) |

| Abdominal pain Intermittent melena | 8 (32.0) 11 (44.0) |

| Duration, mo | |

| < 1 | 15 (60.0) |

| > 1 | 10 (40.0) |

| RBC transfusion, U | 19 (76.0) |

| 2-4 | 10 (40.0) |

| 5-16 | 9 (36.0) |

The patients underwent emergency abdominal DSA that was performed with an Integris V3000 Vascular X-ray System (Philips, Ann Arbor, MI, United States) using a nonionic contrast agent (Ultravist, 300 mg I/mL; Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Berlin-Wedding, Germany). A 5-F introducer sheath was inserted into the right femoral artery using the improved Seldinger’s technique. The tip of a 5-F Yashiro catheter was inserted into the celiac trunk, and the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries. Each DSA series lasted 20 s with 2 photos taken per second and using a 15 mL contrast bolus injected with a 903300 D Power Injector (Liebel-Flarsheim, Cincinnati, OH, United States). We evaluated the DSA images to determine their exact location, feeding artery, blood supply, number, boundary, draining veins and bleeding signs (extravasation of contrast agent). In the cases of tumor with severe blood loss, anemia or signs of obvious active bleeding, the tumor was embolized with gelfoam particles for hemostasis. The time of the DSA procedure was also recorded.

All small bowel tumors underwent surgical resection following the guided site of interventional DSA. The operation records and histopathological exams included locations, capsule integrity, size, internal structure of the tumor, suspicious lymph nodes near the tumor, and pathologic diagnosis (histopathological and immunohistochemical findings). The diagnosis of the GISTs was based on the WHO classification system for soft-tissue tumors [Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA. Pathology and Genetics. Tumors of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC Press (2000)].

The clinical features of the 25 cases of small bowel GISTs are summarized in Table 1. The patient ages ranged from 34- to 70-year-old (average: 52 ± 12 years). Six patients were 30- to 39-year-old and 19 were over 40-year-old. The patients’ chief clinical sign was acute or subacute OGIB with varying degrees of anemia. Forty-four percent of the patients had intermittent melena, and one patient also had acute hematemesis. The clinical history of GI bleeding ranged from 3 d to 10 years. Hemoglobin levels were 34 to 104 g/L (average: 68 ± 22 g/L) when patients presented to our hospital. Nineteen patients received a RBC transfusion of 2-16 U (average: 6.5 ± 2.0 U).

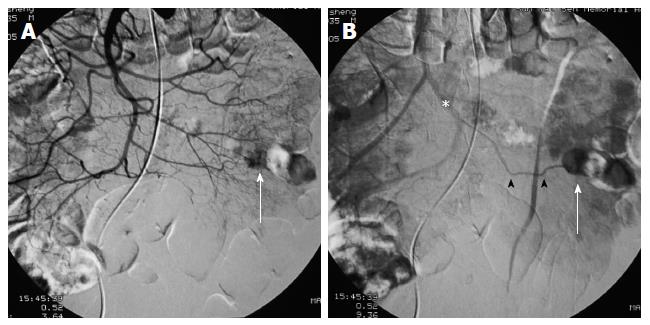

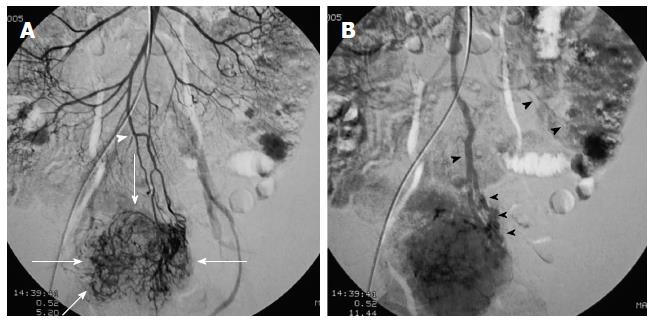

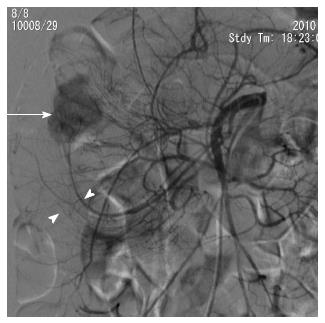

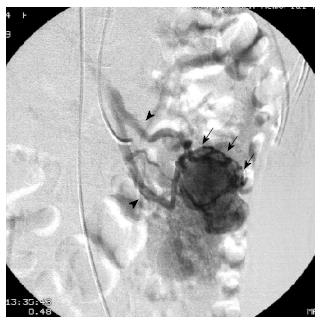

First, abundant blood vessels, appearing as hypervascular tumors, were observed from the early arterial phase to the venous phase in masses of various sizes (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4). The tumors were homogenously well-defined (smooth or mild lobular) or enhanced without filling defects (necrosis), arteriovenous fistulae/malformations or pseudoaneurysms. Second, the feeding artery was not obviously enlarged (Figure 1A) or was only slightly enlarged (Figures 2A and 3) in relation to tumor size. The feeding artery divided into numerous small coiled or hair-like branches into the tumor (Figures 1A, 2A and 3). Third, there was usually only one tumor (Figures 1, 3 and 4); multiple tumors were observed in only a few cases (Figure 2). No abnormal staining of lymph nodes near the tumor was observed (Figures 1B, 2B and 4). Fourth, obvious reticular and thickened draining veins were found in tumors, and the larger tumor, the thicker the draining veins (Figures 2B and 4). The draining veins developed early and merged into the portal vein system (Figures 1B, 2B and 4). These findings were more evident on super-selective angiography (Figure 4). Fifth, signs of active bleeding (extravasation of contrast agent) were not obvious. Although patients had a symptom of acute GI bleeding, no extravasation of contrast agent was detected (Figure 4). Finally, there were special DSA features when intussusception and other complications coexisted (Figure 3).

There were a total of 28 tumors detected by interventional DSA in these patients, with 22 cases involving single tumors and 3 cases involving multiple tumors (2 tumors each). Twenty of the GISTs were located in the jejunum and 8 in the ileum. Eight tumors in 7 patients with a large amount of blood loss were treated with transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) with gelfoam particles during the DSA procedure.

The time per interventional procedure ranged from 22 to 45 min (average: 29 ± 5 min). All patients tolerated the interventional DSA and management well and did not develop any complications related to the procedure.

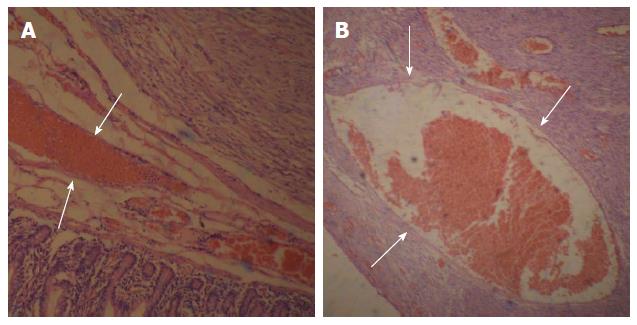

All of the tumors detected on DSA were completely resected and shown to be GISTs of the small intestine based on pathological tests and immunohistochemical analysis. OGIB was resolved immediately after the procedure. In one patient, a tumor was found inside the small intestinal intussusception and correlated with the preoperative DSA findings. The exact location and number of tumors were consistent with the DSA results. The maximum diameter of the resected tumors ranged from 1.2 to 5.5 cm (average: 3.05 ± 1.25 cm) (Table 2). Eight of the tumors had associated ulceration, erosion was observed in 10 tumors, and hyperemia/edema was observed in 10 tumors on the intra-luminal side.

| Finding | n (%) |

| Location | |

| Jejunum | 20 (71.4) |

| Ileum | 8 (28.6) |

| Size (cm) | |

| ≤ 2.0 | 6 (21.4) |

| 2.1-5.0 ≥ 5.1 | 20 (71.4) 2 (7.1) |

| Manifestations | |

| Ulceration | 8 (28.6) |

| Erosion | 10 (35.7) |

| Others | 10 (35.7) |

| Risk of aggressive behavior | |

| Very low Low Moderate | 6 (21.5) |

| 19 (67.9) | |

| 2 (7.1) | |

| High | 1 (3.5) |

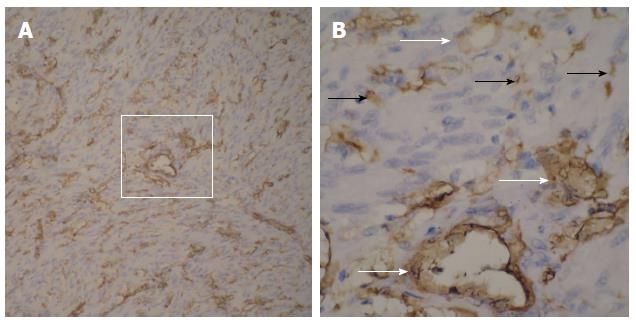

Based on the pathological and immunohistochemical evaluations, for example, hematoxylin-eosin staining and CD34-positivity indicated that abundant blood vessels in various diameters proved that the small bowel GISTs were hypervascular tumors (Figure 5 and Figure 6). The tumors were classified based on their various risks of aggressive behavior as shown in Table 2.

Of all the patients undergoing DSA, the most important reason was acute or subacute OGIB with low hemoglobin levels; the second most important reason was due to the physicians’ clinical experience regarding the use of DSA in the detection of OGIB and the interventional treatment of the source of GI bleeding, such as arteriovenous malformations, artery rupture, and some GI tumors.

For small bowel GISTs, early clinical manifestations are often absent or nonspecific, and mainly depend on tumor size and location. For the 25 patients in the present study, acute or subacute OGIB was the main indication for DSA, which was confirmed with subsequent surgical and pathological results. RBC transfusion, which was performed in the majority of the patients (19/25, 76.0%), was another indication for interventional treatment. Therefore, when conventional endoscopic and imaging examination fails to locate the lesions in patients with bleeding in a timely manner, emergency DSA may be a useful option. Other characteristics of the patients with small bowel GISTs, such as age, sex and abdominal pain, were similar to previous reports in the literature[2,5,6,13,16].

This study showed that there were some common DSA characteristics in small bowel GISTs. Despite the different tumor sizes, DSA can clearly reveal their exact site, range or number, blood supply and complications. Of the 28 small bowel tumors in our study, tumors measuring 2 cm or less (6/28, 21.4%) were also well-defined and exhibited obvious draining veins on the tumor surface with homogenous enhancement. Compared with the findings of Fang et al[17], which showed that draining veins were found only in 27.2% (3/11) of these tumors, we think that the different appearances of the draining veins are mainly based on tumor location, size, and classification. Although CT scans[2,9-11,13,17] also focus on the detection of feeding arteries and tumor blood supply, little attention has been paid to the draining veins of GISTs. In this study, in addition to the clear depiction of feeding arteries, numerous draining veins on tumors also appeared clearly in the early phase of the DSA procedures. The draining veins of the tumors merged into the portal venous system. Additionally, the draining veins were enlarged in proportion to the size of the tumor. We think that this feature may be used as one of the angiographic criterion for small intestinal GISTs and can be used to detect and localize smaller GISTs (especially ≤ 2 cm in our study). In addition, two reasons that the small bowel GISTs were relatively smaller compared with previous reports[1,10,11,14] include tumor bleeding and the timely use of the DSA procedure. Furthermore, to our knowledge, this article presents the largest DSA series of small bowel GISTs to date[13,17-20]. Based on our DSA findings, it is not difficult to detect and make a preoperative diagnosis and to locate small bowel GISTs.

Abdominal CT and MRI play an important role in the diagnosis of small intestinal tumors, especially larger size tumors, and facilitate the evaluation of their extent, fixed tumor structures, staging and the detection of abdominal metastasis[4,6,9-13,21]. Therefore, CT is often the initial imaging modality used to evaluate patients who present with non-specific abdominal symptoms or a palpable abdominal mass. Smaller GISTs typically appear as well-defined soft-tissue and low-density masses that are relatively homogeneous on enhanced CT. When the tumors are larger (usually, > 5 cm), they are often heterogeneous because of necrosis, hemorrhage, and myxoid degeneration. However, the appearance of GISTs on enhanced CT varies depending on the size, location and aggressiveness of the tumor. Wu et al[21] reported a 100 sample series of small bowel GISTs and found that the sensitivity of the detection of enhanced CT was 91%. However, other studies showed that the CT detection rate was low for tumors with intraluminal growth and for smaller sized tumors (< 35 mm)[22,23].

Capsule endoscopy (CE) and double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) have completely changed the approach and launched a new era for clinical management of small bowel diseases[7,8,22,23]. Some studies suggested that these two modalities are diagnostically superior to other routine procedures, such as push enteroscopy, abdominal CT and small bowel angiography, in detecting small bowel lesions[24].

Compared with the diagnostic approaches mentioned above, interventional DSA is helpful and timely for detecting small bowel GISTs in patients with bleeding due to several advantages. Unlike the abdominal CT/MRI, CE or DBE procedures, DSA is more convenient and timely and patients do not need rigorous preoperative preparation[7-10,12,24]. In addition, the procedure time was not too long. Furthermore, the procedure is reasonably sensitive for detecting small bowel GISTs. Finally, if signs of active bleeding are observed during the DSA procedure, interventional radiologists can treat the bleeding. Our results are consistent with previous studies that showed that interventional radiological procedures in the detection of bleeding GISTs of the small bowel were superior to other diagnostic approaches[18].

In this study, the pathological and CD34-positive results showed that GISTs were hypervascular tumors that were free of cystic lesions. This finding may be related to the appearance of some small bowel GISTs on DSA and may indicate one reason for bleeding. However, it is not very clear why some patients exhibited the symptom of intermittent melena.

In general, this study has some limitations. First, the sample of tumors was too small for further analysis, including the number and size (> 5 cm) of the tumors. Second, although acute or subacute bleeding was the main indication for DSA, we found no obvious signs of extravasation of contrast agent, which indicates bleeding. Darnell et al[13] reported that one of three performed DSAs indicated signs of active bleeding. A possible explanation was a temporary resolution of bleeding because of the use of hemostasis and other factors before DSA. This result also explained the history of intermittent bleeding in some patients with GISTs in our study group (11/25, 44.0%). However, based on our experience and knowledge and due to the safety of surgical laparotomy, we performed TAE using gelfoam particles in 7 patients (8 tumors) with severe anemia due to actively bleeding tumors. Third, all tumors detected with DSA were treated with emergency surgery instead of preoperative arterial embolization via catheterization. For most surgeons, biopsy or embolization may increase an unconfirmed risk of rupture (causing peritoneal seeding) and intestinal ischemia[25].

In summary, our study showed that small bowel GISTs had some characteristic DSA features. Emergency interventional DSA was well tolerated in our patients with GI bleeding. We suggest that interventional DSA may be an ideal imaging selection in patients with small bowel GISTs that are unidentified by other methods and may be useful in making the diagnosis of the small bowel GISTs. We believe that interventional DSA is both a useful imaging option for locating and diagnosing of small bowel GISTs in patients with bleeding as well as an effective treatment modality.

Small bowel gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are rare and are often nonspecific or asymptomatic. Because of their deep location and more aggressive biobehavior, by the time these tumors are detected, they are usually larger and may be associated with abdominal masses or metastases. In some small bowel GIST patients with gastrointestinal bleeding and intermittent melena, treatment is delayed for various reasons, such as a resolution of bleeding after medical treatment, negative results from routine endoscopy and imaging analysis, and small tumor size. Furthermore, there have been a few reports on the detailed appearance of these lesions on digital subtraction angiography (DSA) in previous studies. This article demonstrates many new DSA findings in 28 small bowel GISTs in 25 patients.

There are few studies that have focused on the appearance of small bowel GISTs on DSA. In this study, the authors demonstrate new DSA findings and the association between the DSA findings and pathological characteristics.

This is the first study with such a large sample of small bowel GISTs undergoing the DSA procedure. The authors focused on both the arterial phase and venous phase appearances, especially of the draining veins, which may be a very important imaging characteristic for the detection of smaller lesions. For patients with a large amount of blood loss, radiologists could perform interventional therapy to resolve bleeding during the DSA procedure. Therefore, interventional DSA is an effective theranostic approach.

The study provides another safe and effective theranostic modality for managing patients with small bowel bleeding, while other imaging examinations are not able to detect these bleeds.

This is a retrospective study that shows the DSA features of small bowel GISTs. The authors concluded that because of some characteristic DSA features, emergency interventional DSA is both a useful imaging selection in locating and diagnosing of small bowel GISTs in patients with bleeding, as well as an effective treatment modality. This is a really fine paper. My opinion is that the authors did a great job.

P- Reviewer: Bakoyiannis A, Kim GH, Yang LB S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: AmEditor E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Crosby JA, Catton CN, Davis A, Couture J, O’Sullivan B, Kandel R, Swallow CJ. Malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the small intestine: a review of 50 cases from a prospective database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:50-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pidhorecky I, Cheney RT, Kraybill WG, Gibbs JF. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: current diagnosis, biologic behavior, and management. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:705-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | DeMatteo RP, Lewis JJ, Leung D, Mudan SS, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Two hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recurrence patterns and prognostic factors for survival. Ann Surg. 2000;231:51-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1797] [Cited by in RCA: 1682] [Article Influence: 67.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Burkill GJ, Badran M, Al-Muderis O, Meirion Thomas J, Judson IR, Fisher C, Moskovic EC. Malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor: distribution, imaging features, and pattern of metastatic spread. Radiology. 2003;226:527-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2006;23:70-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1244] [Cited by in RCA: 1304] [Article Influence: 72.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (33)] |

| 6. | Grover S, Ashley SW, Raut CP. Small intestine gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2012;28:113-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nakatani M, Fujiwara Y, Nagami Y, Sugimori S, Kameda N, Machida H, Okazaki H, Yamagami H, Tanigawa T, Watanabe K. The usefulness of double-balloon enteroscopy in gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the small bowel with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Intern Med. 2012;51:2675-2682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen WG, Shan GD, Zhang H, Li L, Yue M, Xiang Z, Cheng Y, Wu CJ, Fang Y, Chen LH. Double-balloon enteroscopy in small bowel tumors: a Chinese single-center study. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3665-3671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Choi H. Imaging modalities of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:907-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sandrasegaran K, Rajesh A, Rushing DA, Rydberg J, Akisik FM, Henley JD. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: CT and MRI findings. Eur Radiol. 2005;15:1407-1414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chamadol N, Laopaiboon V, Promsorn J, Bhudhisawasd V, Pagkhem A, Pairojkul C. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: computed tomographic features. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92:1213-1219. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Lupescu IG, Grasu M, Boros M, Gheorghe C, Ionescu M, Popescu I, Herlea V, Georgescu SA. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: retrospective analysis of the computer-tomographic aspects. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2007;16:147-151. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Darnell A, Dalmau E, Pericay C, Musulén E, Martín J, Puig J, Malet A, Saigí E, Rey M. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31:387-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Saperas E, Dot J, Videla S, Alvarez-Castells A, Perez-Lafuente M, Armengol JR, Malagelada JR. Capsule endoscopy versus computed tomographic or standard angiography for the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:731-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pai M, Frampton AE, Virk JS, Nehru N, Kyriakides C, Limongelli P, Jackson JE, Jiao LR. Preoperative superselective mesenteric angiography and methylene blue injection for localization of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:665-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lin CY, Chuah SK, Wang SH, Tai WC, Wang CC. Primary small bowel malignancy: a 10-year clinical experience from Southern Taiwan. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:756-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fang SH, Dong DJ, Zhang SZ, Jin M. Angiographic findings of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2905-2907. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Basile A, Certo A, Ascenti G, Lamberto S, Cannella A, Medina JG. Interventional radiology in the preoperative management of stromal tumors causing intestinal bleeding. Radiol Med. 2003;106:376-381. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Lin C, Chang Y, Zhang Y, Zuo Y, Ren S. Small duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor presenting with acute bleeding misdiagnosed as hemobilia: Two case reports. Oncol Lett. 2012;4:1069-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jassó A, Bertha L, Gyökeres T, Takács IG, Bursics A. [Small bowel GIST causing gastrointestinal bleeding, diagnosed by preoperative angiography]. Magy Seb. 2007;60:218-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wu TJ, Lee LY, Yeh CN, Wu PY, Chao TC, Hwang TL, Jan YY, Chen MF. Surgical treatment and prognostic analysis for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) of the small intestine: before the era of imatinib mesylate. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rondonotti E, Pennazio M, Toth E, Menchen P, Riccioni ME, De Palma GD, Scotto F, De Looze D, Pachofsky T, Tacheci I. Small-bowel neoplasms in patients undergoing video capsule endoscopy: a multicenter European study. Endoscopy. 2008;40:488-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cheung DY, Lee IS, Chang DK, Kim JO, Cheon JH, Jang BI, Kim YS, Park CH, Lee KJ, Shim KN. Capsule endoscopy in small bowel tumors: a multicenter Korean study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1079-1086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Trifan A, Singeap AM, Cojocariu C, Sfarti C, Stanciu C. Small bowel tumors in patients undergoing capsule endoscopy: a single center experience. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:21-25. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Peparini N, Chirletti P. Tumor rupture during surgery for gastrointestinal stromal tumors: pay attention! World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2009-2010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |