Published online Sep 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.13153

Revised: May 5, 2014

Accepted: May 26, 2014

Published online: September 28, 2014

Processing time: 213 Days and 13.6 Hours

AIM: To investigate the outcome of repeating endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP) after initially failed precut sphincterotomy to achieve biliary cannulation.

METHODS: In this retrospective study, consecutive ERCPs performed between January 2009 and September 2012 were included. Data from our endoscopy and radiology reporting databases were analysed for use of precut sphincterotomy, biliary access rate, repeat ERCP rate and complications. Patients with initially failed precut sphincterotomy were identified.

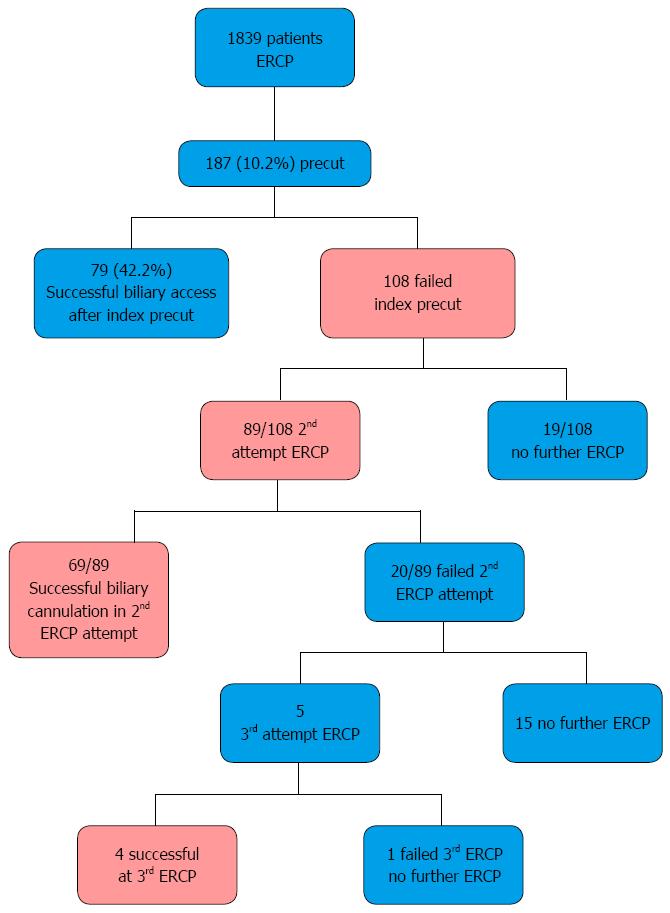

RESULTS: From 1839 consecutive ERCPs, 187 (10%) patients underwent a precut sphincterotomy during the initial ERCP in attempts to cannulate a native papilla. The initial precut was successful in 79/187 (42%). ERCP was repeated in 89/108 (82%) of patients with failed initial precut sphincterotomy after a median interval of 4 d, leading to successful biliary cannulation in 69/89 (78%). In 5 patients a third ERCP was attempted (successful in 4 cases). Overall, repeat ERCP after failed precut at the index ERCP was successful in 73/89 patients (82%). Complications after precut-sphincterotomy were observed in 32/187 (17%) patients including pancreatitis (13%), retroperitoneal perforations (1%), biliary sepsis (0.5%) and haemorrhage (3%).

CONCLUSION: The high success rate of biliary cannulation in a second attempt ERCP justifies repeating ERCP within 2-7 d after unsuccessful precut sphincterotomy before more invasive approaches should be considered.

Core tip: Selective biliary cannulation during endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreaticography (ERCP) fails in 5%-15%, even in expert high volume centres. Precut sphincterotomy facilitates biliary access, but also has a failure rate. Alternative, more invasive options for achieving biliary therapy, such as percutaneous-endoscopic or endoscopic ultrasound guided rendez-vous procedure, percutaneous transhepatic or surgical intervention include a considerable morbidity. This study demonstrates that repeating the ERCP within a few days after initial failed precut is a successful strategy in the majority of patients and should be tried before contemplating more invasive, alternative interventions.

- Citation: Pavlides M, Barnabas A, Fernandopulle N, Bailey AA, Collier J, Phillips-Hughes J, Ellis A, Chapman R, Braden B. Repeat endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography after failed initial precut sphincterotomy for biliary cannulation. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(36): 13153-13158

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i36/13153.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.13153

Successful biliary therapy during endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) requires selective cannulation of the bile duct. Despite advances and new developments in endoscopic accessories such as catheters, guide-wires and sphincterotomes, selective biliary cannulation fails in 5%-15% of cases, even in expert high volume centres[1].

In the wider endoscopic community, biliary cannulation success rates are even lower. In a large scale, prospective multicentre study performed in 66 hospitals across England, selective deep biliary cannulation was achieved only in 84%. The study had been organized by the British Society of Gastroenterology in 2004 and included 3209 patients with native papilla[2].

Precut sphincterotomy facilitates selective bile duct access during ERCP in patients in whom conventional biliary cannulation has failed. Precut sphincterotomy seems to be associated with a higher procedure related complication rate in many studies, such as haemorrhage, perforation and especially acute post-ERCP pancreatitis, but this is probably due to an increased number of cannulation attempts in patients undergoing precut sphincterotomy in the end, while the complication rate is lower if precut sphincterotomy is carried out early (< 10 attempts)[1,3,4].

However, precut sphincterotomy does not always achieve primary biliary cannulation success. Prolonged cannulation and precut attempts often result in papillary oedema which renders the bile duct insertion even more difficult.

In cases with failed biliary cannulation during ERCP, several options exist for achieving biliary therapy, such as percutaneous-endoscopic or endoscopic ultrasound guided rendezvous procedure, percutaneous trans-hepatic biliary therapy, or surgical intervention (when appropriate for the patient). Unfortunately, these alternative techniques are more invasive and include a considerable morbidity or are not widely available (e.g., endoscopic ultrasound guided biliary drainage)[5,6].

In this retrospective cohort study, we investigated whether it is justifiable to repeat ERCP within a few days after an initially failed precut before considering more invasive strategies such as rendezvous techniques, percutaneous trans-hepatic cholangiography or surgery.

A retrospective cohort study of all ERCPs performed between January 2009 and September 2012 was conducted. Consecutive ERCPs were identified from endoscopy (Unisoft Medical Systems, Enfield, Middlesex, United Kingdom) and radiology (Centricity® Enterprise Web, GE Medical Systems) reporting databases and were analysed for use of precut sphincterotomy, biliary access rate, repeat ERCP rate and complications. All patients with a naïve papilla that could be reached by using a duodenoscope were included in this study and patients with initially failed precut sphincterotomy were identified. A retrospective review of the patients’ electronic records was undertaken to identify post procedural outcomes. All ERCPs were clinically indicated and were performed as part of the patients’ routine care. All patients agreed to have the ERCPs and gave written informed consent.

All endoscopists (Barnabas A, Collier J, Phillips-Hughes J, Ellis A, Chapman R, Braden B) routinely perform freehand cannulation or a wire-guided cannulation technique when attempting to cannulate a native papilla. A sphincterotome with a 4.4 F tip and a straight 0.035-inch guide-wire are usually used. ERCP trainees were involved with initial attempts of papillary cannulation, but precut techniques were exclusively performed by senior consultant endoscopists. The preferred precut sphincterotomy method is a needle-knife technique using a 3-mm-long needle-knife (Olympus Optical Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). The cut is aimed from the top of the papillary orifice upwards in a 11 o’clock direction un-roofing the biliary orifice and exposing the opening of the distal bile duct, which is selectively cannulated with a guide-wire passed through a sphincterotome or cannula. After successful placement of the guide-wire into the bile duct the sphincterotomy is completed in a conventional manner with therapeutic interventions carried out as indicated by the findings (e.g. stent insertion, stone extraction, dilatation). The number of failed cannulation attempts of the papilla before starting precut and the attempts of bile duct cannulation after precut procedure were at the discretion of the endoscopist.

After November 2010, unless contraindicated, patients routinely received 100 mg of diclofenac per rectum prior to all ERCPs as prophylaxis for post ERCP pancreatitis.

The primary outcome was the success of repeated ERCP after initially failed precut sphincterotomy. Precut sphincterotomy and ERCP was deemed successful if cannulation of the bile duct was achieved enabling appropriate therapy.

Procedure-related complications were defined as adverse clinical events or unexpected clinical outcomes related to the procedure. Specifically, this study assessed 30 d mortality, post-ERCP pancreatitis, bleeding, cholangitis, perforation, and any unexpected adverse clinical event.

Post-ERCP pancreatitis was defined according to consensus criteria as abdominal pain and an increase of serum amylase levels at least three times greater than the normal upper limit requiring hospitalization for at least 2 nights[7]. Clinical bleeding was defined as the presence of clinical evidence of hemorrhage (melaena, haematochezia or haematemesis) with a drop of over 10% in hemoglobin concentration, a need for endoscopic intervention, or a need for hospitalization within 7 d post-procedure.

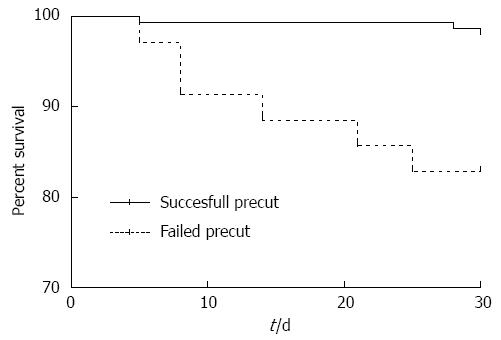

Data are presented as average and standard deviation or median and inter-quartile range as appropriate. Categorical data was analysed using Fisher’s exact test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Kaplan Meier curves were used to compare the 30 d mortality of those who failed precut and those who underwent successful precut. Log-rank (Mantel Cox) test was used to test for significant differences between the curves. Statistical analyses were carried out using the GraphPad Prism software (version 5, Graphpad Software, Inc.).

A total of 1839 ERCPs in patients with a native papilla were performed during the study period. One hundred eighty-seven (10.2%) patients (107 female, 80 male) were identified who underwent a precut sphincterotomy during the initial ERCP in attempts to cannulate a native papilla. Indications for ERCP in these 187 patients included common bile duct stones (43%), biliary leak (7%), obstructive jaundice (18%), cholangiocarcinoma (3%), pancreatic cancer (10%) and metastatic disease from other cancers (2%).

In 79 patients (42.2%) a precut sphincterotomy led to common bile duct cannulation at the initial ERCP. ERCP was repeated in 89 of the 108 patients with failed initial precut sphincterotomy. Repeat ERCP performed a median of 4 d [interquartile range (IQR) 3-6 d] after initial precut sphincterotomy allowed successful biliary cannulation in 69/89 patients (77.5%). In 5 patients with failed second attempt, ERCP was repeated a third time and biliary access was gained in four. In total, repeat ERCP after failed primary precut ERCP was successful in 73/89 patients (82.0%). Overall the biliary cannulation was successful in 152 of 187 patients (81.3%). Figure 1 illustrates the management of patients and biliary cannulation outcomes.

Complications were observed in 32/187 patients having pre-cut sphincterotomy (17.1%). Twenty-four patients (12.8%) developed pancreatitis, mild or moderate in severity. All cases of pancreatitis were treated conservatively. After pre-cut sphincterotomy, 2 patients (1.1%) had retroperitoneal perforations which settled on antibiotics and conservative management. Five patients (2.7%) suffered bleeding complications after precut-sphincterotomy. One of these patients required mesenteric angiography and embolisation, another one endoscopic treatment with heater probe. The bleeding settled spontaneously in the three other patients. One patient (0.5%) developed biliary sepsis following his procedure which was successfully treated with antibiotics.

There were no significant differences between the complication rate after the index ERCP (24/187, 12.8%) and after a subsequent procedure [8/93 (8.6%), P = 0.33].

Biliary access was not successful despite pre-cut in 35/187 (18.7%). Twelve patients did not have any further invasive interventions due to frailty or a lapse in the indication for ERCP. Ten patients went on to have surgical treatment without any other intervention (8 cholecystectomies and common bile duct exploration, 1 choledochojejunostomy and roux loop, 1 Whipple’s procedure). There were no major complications from surgical interventions. Ten patients went on to have percutaneous biliary cholangiography (PTC) and attempted intervention. Patients who underwent PTC did not have any complications. In one case PTC failed twice and the patient went on to have a Whipple’s procedure. One patient had an endoscopic ultrasound of the common bile duct which revealed no gall stones and no further procedures were performed. Two patients were transferred back to their referring hospitals and the data regarding their final outcome are missing.

Nine (4.8%) of the 187 patients died within 30 d of their latest ERCP. There was a significantly higher 30 d mortality in patients where biliary access was not achieved endoscopically despite precut (6/35, 17%) compared to those who had successful biliary cannulation after precut (3/152; 2%, P = 0.0016). The Kaplan Meyer curves for 30 d mortality are shown in Figure 2.

The cause of death could be retrospectively established only in 6 of the 9 patients. In all cases patients died from underlying advanced malignancy.

Selective bile duct cannulation is the prerequisite for all endoscopic biliary therapeutic interventions, but this cannot always be achieved easily. Difficulties in selective bile duct cannulation can be encountered due to anatomic restraints, papillary spasms or impacted stones[2]. In cases where cannulation is difficult, precut sphincterotomy can provide access into the distal bile duct. Several techniques such as needle-knife papillotomy, fistulotomy, and trans-pancreatic septotomy have been described[8].

Prolonged or repeated attempts of cannulation of the papilla and the diathermy effect of the precut sphincterotomy can result in papillary oedema with distortion of the papillary anatomy and narrowing of the distal common bile duct which renders insertion into the bile duct even more difficult. Furthermore, the view can become restricted by bleeding. Therefore, it appears worthwhile to repeat the ERCP in a short interval following the initial precut sphincterotomy when the cautery induced papillary oedema has resolved. In our experience, the oedema caused by initial cannulation attempts and cautery usually resolves three to five days after the initial precut, and the anatomy of the papilla becomes clearer. Often the opening of the bile duct can be identified then facilitating the biliary cannulation. This experience in our centre is also supported by evidence from another published series where the success rate of cannulation was significantly higher after an interval of 2-3 d vs an interval of 1 d between the index and subsequent procedure[9].

In the present study, selective biliary cannulation of the naïve papilla was achieved in 89.8% of cases with the remaining 10.2% of cases necessitating precut sphincterotomy to facilitate biliary access. The biliary cannulation success rate of 89.8% is in keeping with other published series which report success rates of 80%-95%[1,2,10]. Including the 79 cases where precut allowed biliary access at the index ERCP, selective deep biliary cannulation was possible in 1731 of 1839 patients (94.1%) during the first ERCP.

In the remaining 5.9%, we found a success rate for biliary cannulation of 77% in a repeat ERCP after a median of 4 d following a failed initial precut sphincterotomy. When the results of the four cases that had successful biliary cannulation in a third ERCP attempt were added, the overall rate of biliary cannulation in repeat ERCP after failed initial precut increases to 82%. There were no significant differences in the rates of complications between the index and subsequent ERCP and there was no procedure related mortality.

Biliary cannulation at the time of precut sphincterotomy at the index ERCP was successful in 79/187 (42.2%). This rate appears lower than rates reported in the literature (72.3%-92%)[9-12]. However, comparison with these other published series is difficult as they mostly represent the results of a single endoscopist[10-12]. Furthermore, some of these studies do not report the success rates of biliary cannulation without precut[11] while one study reports a need for precut in 23.3% of their patients[10]. Our overall cannulation rate of 81.3% for those patients needing a precut sphincterotomy is comparable to those reported in other similar studies[9,12].

Our success rate of 82% for biliary cannulation in patients undergoing a repeat ERCP after failed initial precut sphincterotomy seems to be higher than in similar retrospective studies with smaller numbers. An Irish group[13] repeated the ERCP after failed needle knife fistulotomy in 19 patients and gained biliary access in 13 (68%). Donnellan et al[14] reported 75% success of repeat ERCP in a series of 51 patients with failed use of a needle knife sphincterotomy. In addition the overall complication rate reported here (17.1%) is again similar to other published series[9-11].

One interesting observation was that the 30 d mortality in those who failed biliary cannulation despite precut was higher compared to those where biliary cannulation was successful. Furthermore, mortality in all patients within the study was attributed to advanced malignancy, suggesting that in the setting of biliary obstruction due to malignancy, failure to achieve biliary cannulation implies advanced disease and may be considered as a bad prognostic factor.

The choice of the precut technique and the number of cannulation attempts before and after precut sphincterotomy were at the discretion of the endoscopist and this is a limitation of this study. However, none of our endoscopists routinely performs supra-papillary fistulotomy or trans-septal pancreatic sphincterotomy, all use a freehand incision technique starting at the papillary orifice and extending cranial using a short pulsed cutting current. In addition, this is a retrospective non randomised observational study which may be limited by selection bias; prospective data would be desirable.

The clinical decision to repeat the ERCP needs to be seen in the context of the complication rates of the alternative strategies. According to Oh et al[15], overall PTC complications occur in 12.9% while severe complications such as haemobilia, haemoperitoneum, or ductal injury are observed in 8.2%. Weber et al[16] reports lower overall complication rates of 9.3% and also less common severe complications in 4%. The local expertise in interventional radiology, surgery, and ERCP should also guide the clinical decision for the particular patient whether repeat ERCP or alternative options might be more appropriate.

In conclusion, the high success rate of biliary cannulation in a second attempt ERCP justifies repeating ERCP within 2-7 d after unsuccessful initial precut sphincterotomy before more invasive approaches such as percutaneous cholangiography or surgery should be considered. Repeat ERCP after previously failed precut sphincterotomy obtains biliary access in about two thirds of patients and allows definite biliary therapy.

The endoscopic access to the bile duct for therapeutic procedures such as stone extraction or stent insertion for biliary drainage can be technically difficult. The selective cannulation of the bile duct during endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) fails in about 10% of cases, even in expert high volume centres.

Precut sphincterotomy is a technique to gain access to the bile duct by a controlled incision when standard cannulation techniques have failed. In experienced hands, early precut sphincterotomy reduces the post-ERCP pancreatitis rate while repeated cannulation attempts increase it. However, it remains unclear how to manage patients with failed precut sphincterotomy who require biliary therapy.

In the present study, the outcome of repeating ERCP after a failed initial precut sphincterotomy has been analysed. In about two thirds of patients with a failed initial precut sphincterotomy, the repeat ERCP was successful and obtained biliary access allowing definite biliary therapy for these patients.

The high success rate of biliary cannulation in a repeat ERCP in this study encourages a second ERCP attempt within 2-7 d as a reasonable approach in patients with failed initial precut sphincterotomy.

During ERCP, the selective cannulation of the bile duct by guidewires followed by special catheters enables therapeutic procedures such as stone extraction, balloon dilatation or stent insertion. Precut sphincterotomy is defined as a controlled incision into the ampulla Vateri or into the common bile duct to achieve selective biliary cannulation.

Despite being a retrospective series, the high rate of success of 2nd attempt after initial failed pre-cut cannulation is noteworthy.

P- Reviewer: Kalayci C, Tripathi D S- Editor: Nan J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Cennamo V, Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Eusebi LH, Ceroni L, Laterza L, Fabbri C, Bazzoli F. Can early precut implementation reduce endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related complication risk? Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Endoscopy. 2010;42:381-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Williams EJ, Ogollah R, Thomas P, Logan RF, Martin D, Wilkinson ML, Lombard M. What predicts failed cannulation and therapy at ERCP? Results of a large-scale multicenter analysis. Endoscopy. 2012;44:674-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bailey AA, Bourke MJ, Kaffes AJ, Byth K, Lee EY, Williams SJ. Needle-knife sphincterotomy: factors predicting its use and the relationship with post-ERCP pancreatitis (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:266-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Gong B, Hao L, Bie L, Sun B, Wang M. Does precut technique improve selective bile duct cannulation or increase post-ERCP pancreatitis rate? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2670-2680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Brauer BC, Chen YK, Fukami N, Shah RJ. Single-operator EUS-guided cholangiopancreatography for difficult pancreaticobiliary access (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:471-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Giovannini M, Moutardier V, Pesenti C, Bories E, Lelong B, Delpero JR. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided bilioduodenal anastomosis: a new technique for biliary drainage. Endoscopy. 2001;33:898-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 480] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Saritas U, Ustundag Y, Harmandar F. Precut sphincterotomy: a reliable salvage for difficult biliary cannulation. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Kim J, Ryu JK, Ahn DW, Park JK, Yoon WJ, Kim YT, Yoon YB. Results of repeat endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography after initial biliary cannulation failure following needle-knife sphincterotomy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:516-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Akaraviputh T, Lohsiriwat V, Swangsri J, Methasate A, Leelakusolvong S, Lertakayamanee N. The learning curve for safety and success of precut sphincterotomy for therapeutic ERCP: a single endoscopist’s experience. Endoscopy. 2008;40:513-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Harewood GC, Baron TH. An assessment of the learning curve for precut biliary sphincterotomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1708-1712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Robison LS, Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM. Safety and success of precut biliary sphincterotomy: Is it linked to experience or expertise? World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2183-2186. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kevans D, Zeb F, Donnellan F, Courtney G, Aftab AR. Failed biliary access following needle knife fistulotomy: is repeat interval ERCP worthwhile? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1238-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Donnellan F, Enns R, Kim E, Lam E, Amar J, Telford J, Byrne MF. Outcome of repeat ERCP after initial failed use of a needle knife for biliary access. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1069-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Oh HC, Lee SK, Lee TY, Kwon S, Lee SS, Seo DW, Kim MH. Analysis of percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy-related complications and the risk factors for those complications. Endoscopy. 2007;39:731-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Weber A, Gaa J, Rosca B, Born P, Neu B, Schmid RM, Prinz C. Complications of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage in patients with dilated and nondilated intrahepatic bile ducts. Eur J Radiol. 2009;72:412-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |