Published online Sep 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.13044

Revised: June 3, 2014

Accepted: June 14, 2014

Published online: September 28, 2014

Processing time: 214 Days and 16.9 Hours

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a complex, immune-mediated disorder that often requires a multi-modality approach for optimal diagnosis and management. While traditional methods include ileocolonoscopy and radiologic modalities, increasingly, capsule endoscopy (CE) has been incorporated into the algorithm for both the diagnosis and monitoring of CD. Multiple studies have examined the utility of this emerging technology in the management of CD, and have compared it to other available modalities. CE offers a noninvasive approach to evaluate areas of the small bowel that are difficult to reach with traditional endoscopy. Furthermore, CE maybe favored in specific sub segments of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as those with IBD unclassified (IBD-U), pediatric patients and patients with CD who have previously undergone surgery.

Core tip: Crohn’s disease (CD) is a complex, immune-mediated disorder that often requires a multi-modality approach for optimal diagnosis and management. Over the past decade, capsule endoscopy (CE) has increasingly found a place in the algorithm for the diagnosis, treatment and monitoring of CD. CE potentially offers a noninvasive approach to evaluate areas of the small bowel that may be difficult to access with traditional endoscopy. Furthermore, CE has potential application for specific subsegments of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as those with IBD unclassified, pediatric patients and patients with CD who have previously undergone surgery.

- Citation: Hudesman D, Mazurek J, Swaminath A. Capsule endoscopy in Crohn’s disease: Are we seeing any better? World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(36): 13044-13051

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i36/13044.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.13044

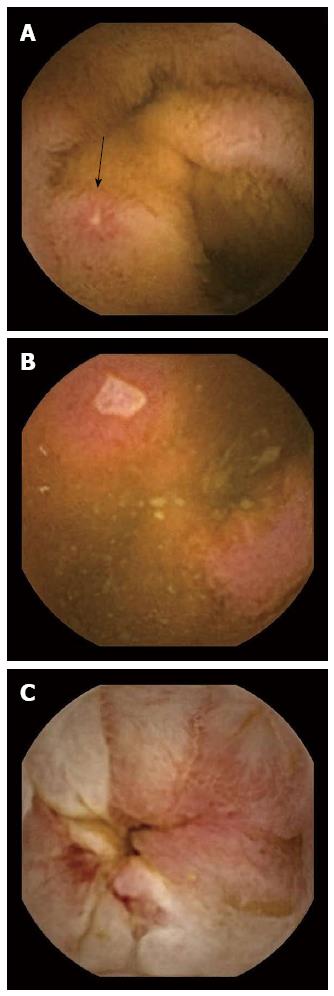

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a complex, immune-mediated condition. Diagnosis and management requires information from multiple modalities. These include clinical symptomatology, serologic and fecal testing, endoscopic assessment with histopathologic analysis and radiologic imaging. While the majority of CD patients have involvement of the small bowel, up to 30% have disease that is confined to the small-bowel alone[1]. Historically, the small bowel was assessed using small bowel radiography, ileocolonoscopy, or push enteroscopy. With advances in technology and imaging, there are now other options for evaluating the small bowel including computed tomographic enterography (CTE), magnetic resonance enterography (MRE), contrast ultrasonography, double balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy (CE). CE offers a sensitive and noninvasive strategy for establishing the correct diagnosis, and the monitoring of disease activity. Findings on CE in CD include aphthae, deep ulcerations, and stricturing disease (Figure 1). Furthermore, CE is particularly useful in areas of the gastrointestinal tract that are not optimally seen on conventional endoscopy or radiologic imaging.

CE (Given, Yoqneam, Israel; Pill-Cam SB) was Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved in 2001 for evaluation of the small bowel. CE is currently approved for the evaluation of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding and iron deficiency anemia in patients with a normal upper and lower endoscopy, as well as for the evaluation and monitoring of CD. Given imaging has recently launched its third generation of small bowel capsules, PillCam SB3, which has improved image detail, and adaptive frame rate technology leading to increased visualization of the small bowel, and improved efficiency. A competing capsule system was developed by Olympus (Lake Success, NY; EndoCapsule) that was FDA approved in 2007. Although the technology continues to improve, the main barrier to CE use in IBD has been its lack of specificity and concern for retention in the small bowel due to strictures[2-4].

Clinicians have relied upon endoscopic and histologic evaluation coupled with small bowel imaging, to define the location and extent of involvement in CD. Improvements in imaging technology have now led to the widespread use of cross sectional imaging in the diagnosis of CD (Table 1).

| Ref. | Compared modality | n | Diagnostic yield of VCE | Incremental yield of VCE | P value |

| Albert et al[5] | MRE | 27 | 93% | 15% | NS |

| SBEC | 60% | ||||

| Hara et al[6] | CTE | 17 | 71% | 18% | NS |

| Ileoscopy | 6% | ||||

| SBFT | 47% | ||||

| Solem et al[7] | CTE | 28 | 83% | 1% | NS |

| Ileocolonoscopy | 9% | ||||

| SBFT | 18% | ||||

| Dionisio et al[9] | SBR | 428 | 58% | 37% | < 0.0001 |

| Ileocolonoscopy | 236 | 64% | 15% | 0.000 | |

| CTE | 119 | 70% | 39% | < 0.00001 | |

| PE | 102 | 50% | 42% | < 0.00001 | |

| MRE | 123 | 50% | 7% | NS | |

| Jensen et al[10] | MRE | 93 | 100% | 27% | 0.03 |

| CTE | 100% | 19% | NS |

A number of studies have compared radiologic imaging studies to CE in CD. Albert et al[5] prospectively compared CE to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and small bowel enteroclysis (SBEC) in 52 known or suspected CD patients. Of the 52 patients included in the study, 41 were confirmed to have CD. Following radiologic testing, 14 patients were noted to have strictures, with only the 27 remaining patients undergoing CE. CE detected small bowel lesions in 93% of patients, as compared to 78% and 33% for MRI and SBEC, respectively. Although the absolute difference in sensitivity favored CE, the study was underpowered to achieve statistical significance.

Hara et al[6] prospectively imaged the small bowel of 17 patients with known or suspected CD with CE, CTE, colonoscopy with ileoscopy, and small bowel follow through (SBFT). The mean time between the first and last exam was 20 wk. The diagnostic yield, defined as the number of patients with evidence of CD over the number of patients studied, was 71% with CE, 65% with ileoscopy, 53% with CTE, and 24% with SBFT. Due to the small sample size, the study did not reach statistical significance. This study was further limited by a lack of specificity as any erosion or ulcer seen on capsule endoscopy or ileoscopy was classified as CD. A major limitation of small bowel imaging is the lack of a reference standard for the diagnosis of CD. Without a gold standard, a sensitivity or specificity of CE in diagnosing small bowel CD cannot be calculated.

Solem et al[7] conducted the only prospective study to overcome this limitation directly comparing CE to CTE, ileocolonoscopy, and SBFT using a consensus diagnosis based on clinical presentation, laboratory data, and the four imaging studies. Each interpreter classified patients with either active, suspicious, inactive or absent CD. These studies were performed sequentially over 4 d with CTE as the first exam. If no strictures were seen on radiologic imaging then the patient underwent CE followed by SBFT. Forty-two patients enrolled in the study, but only 28 underwent CE secondary to stricture, abscess, or drop out. The authors found that the sensitivity of CE for active CD did not differ significantly from the other three modalities. The sensitivities were 83% for CE, 82% for CTE, 74% for ileocolonoscopy, and 65% for SBFT. The specificity of CE, however, was 53%, which was significantly lower than all other modalities.

Using histopathology for diagnosis of CD, Dubcenco et al[8] evaluated the accuracy of CE in known or suspected CD. Thirty-nine patients without strictures underwent ileocolonoscopy, small bowel series (36 with SBFT and 3 with small bowel enema), and CE within an average of 22 d. Histology was able to confirm disease in 25/39 patients, exclude disease in 10/39 patients, and in 4 patients the tissue was not accessible. The sensitivity and specificity for CE was 89.6% and 100% respectively, with the sensitivity and specificity for small bowel series was 27.6% and 100% respectively.

A meta-analysis was performed by Dionisio et al[9] including 19 trials, comparing CE to small bowel radiography (SBR), ileocolonoscopy, CTE, push enteroscopy (PE), and MRE in nonstricturing CD. The primary outcome measure was weighted incremental yield (IYw), defined as the diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy minus the diagnostic yield of the comparative modality. For suspected CD, CE was superior to CTE with an IYw of 47% (68% vs 21%), SBR with an IYw of 32% (52% vs 16%), and ileocolonoscopy with an IYw of 22% (47% vs 25%). For known CD, CE was superior to PE with an IYw of 57% (66% vs 9%), SBR with an IYw of 38% (71% vs 36%), and CTE with an IYw of 32% (71% vs 39%). There was no benefit found of CE over MRE likely secondary to the small sample size in this meta-analysis.

Jensen et al[10] evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of CE compared to CTE and MRE. This study was not included in the previously mentioned meta-analysis. Ninety-three patients with suspected or newly diagnosed CD were enrolled in the study. Twenty-one patients were diagnosed with terminal ileal CD based on the gold standard of histopathology from ileocolonoscopy and/or surgery. Based on the 21 patients with ileal CD, the sensitivity of CE compared to CTE was 100% vs 76%, respectively (P = 0.03). The sensitivity of CE was higher than MRE, 100% vs 81%, respectively; however this was not statistically significant. Specificities and positive predictive values were comparable across the three modalities.

The pediatric population with CD poses another area where the use of CE may prove beneficial. The FDA initially approved CE for pediatric use between the ages of 10 and 18 years of age in 2003, then expanded this age range in 2009 for children as young as 2 years of age[11]. Physiologic differences exist between children and adults that change the risks associated with sedation in the pediatric population, and may result in a higher threshold to perform an invasive endoscopy in children. CE was therefore studied as an alternative to traditional endoscopy in pediatric patients with suspected CD. In one study, MRE was compared to capsule endoscopy in a pediatric population with suspected CD[12]. Ileocolonoscopy was the gold standard, and 19/60 patients included in this study were diagnosed with CD. The sensitivity and specificity of CE and MRE were comparable, 91%, 92% and 100%, 97.6%, respectively.

A study by Levesque et al[13] investigated whether CE was a cost effective tool in evaluating small bowel CD in patients with two previous negative tests using a decision analytic model. In this model, CE was not a cost-effective strategy after a negative ileocolonoscopy and a negative radiologic study (either CTE or SBFT) with a QALY of $500000. The high cost of capsule endoscopy is directly related to the poor specificity of the test, and from a lack of standardization in grading and diagnosing CD. A limitation of this study was the model did not take into account the extent or severity of the disease, or the costs associated with changes in management, or lack thereof.

Based on the most recent evidence based recommendations[14], patients with a high suspicion for CD with a negative ileocolonoscopy should next undergo small bowel imaging. If the patient has signs or symptoms of a stricture and/or obstruction the modality of choice is either CTE, MRE, or patency capsule. If there are no signs or symptoms of obstruction, CE is a good option due to its high sensitivity.

In approximately 15% of patients with isolated colitis it is difficult to definitively distinguish between CD and ulcerative colitis (UC)[15,16]. These patient phenotypes were originally called indeterminate colitis (IC)[17], and are now classified as IBDU. The clinical course and prognosis of IBDU may be worse than UC, especially in patients that have undergone an ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) (Table 2)[18].

Maunoury et al[19] evaluated the role of CE in 30 patients with IBDU and negative ASCA and pANCA. As in the paper cited above, the definition of suspected CD that was used was the presence of three or more small bowel ulcerations, however this definition has not been prospectively validated. Five patients had findings suspicious of CD. In long term follow up, another five patients with normal CE were diagnosed with CD on repeat ileocolonoscopy.

Mehdizadeh et al[20] evaluated the utility of CE in ulcerative colitis (UC) and IBDU. The indications for CE in UC patients were atypical symptoms, disease refractory to medical therapy, and new onset symptoms after total proctocolectomy with IPAA. Nineteen of the 120 patients (16%) had findings consistent with CD, defined as three or more small bowel ulcerations. In addition, 6 of the 21 patients (29%) who had undergone surgical treatment for UC (IPAA) were found to have CD.

Murrell et al[21] investigated the role of preoperative CE in predicting outcomes after IPAA. This retrospective study identified 68 patients, 48 with UC and 20 with IBDU, who had a CE prior to surgery. CE was positive in 15 patients defined as ulcerations, erosions, or erythema. There was no correlation found between positive CE findings and acute pouchitis, chronic pouchitis, or de novo CD over a median follow up time of 12 mo.

We believe that all patients with IBDU should have some form of small bowel imaging to evaluate for CD, with capsule endoscopy as one of the options. Even if the decision to proceed with surgery is unchanged by the findings of a few nonspecific ulcerations in the small bowel, it may be useful to help set expectations for disease course subsequent to IPAA construction.

CD typically recurs after ileocolonic resection just proximal to the surgical anastomosis. Endoscopic recurrence rates range from 70%-90% at one year with clinical recurrence rates of about 30% at three years[22,23]. The current recommendation for diagnosing recurrent CD is an ileocolonoscopy between 6 mo to 1 year after resection[24,25]. Noninvasive techniques including CE have been studied to asses for postoperative recurrence of CD. Aside from the benefit of a noninvasive test, CE should theoretically improve visualization of the neoterminal ileum, as the altered postoperative anatomy often can complicate intubation and visualization of the neoterminal ileum with standard ileocolonoscopy (Table 3).

Bourreille et al[26] prospectively compared ileocolonoscopy (gold standard) to CE in the postoperative setting in 32 patients at a median time of 6 mo after surgery. Two independent observers interpreted the CE results. One patient was excluded because his neoterminal ileum was not visualized with ileocolonoscopy. Ileocolonoscopy detected recurrence in 19 of the 21 patients with a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 100%. In comparison, the sensitivity and specificity of CE were 62%-76% and 90%-100%, respectively. Interestingly, CE found proximal small bowel lesions, out of reach of the ileocolonoscopy, in two thirds of the patients, however these findings are of uncertain clinical significance.

A similar study by Pons Beltran et al[27] reached a different conclusion. Out of 19 evaluable patients, ileocolonoscopy detected recurrence in only 25% of the patients, while capsule endoscopy detected recurrence in 68% of the patients. As in the previous study 59% had proximal small bowel lesions found on CE. The low detection rates of ileocolonoscopy are partially explained by the postsurgical anatomy, where the neoterminal ileum could not be reached in 3 patients. All of the patients included had a side to side anastomosis which may limit visualization of the neoterminal ileum. When assessing for patient comfort, all patients preferred CE over ileocolonoscopy.

All of the mentioned studies have small samples sizes. We do not recommend replacing ileocolonoscopy with CE for evaluation for recurrent CD at a surgical anastomosis that is reachable via ileocolonoscopy. However, in patients where the neoterminal ileum cannot be intubated or in patients with symptoms or abnormal labs (elevated C-reactive protein or anemia) with a negative ileocolonoscopy. CE may identify inflammation elsewhere in the small bowel, though we expect this to be a small group of patients.

There is limited data on how CE may change management in patients with established CD (Table 4).

In a retrospective cohort of 71 established CD patients, Dussault et al[28] evaluated how CE impacts treatment decisions. These patients underwent CE for either unexplained anemia, discrepancy between clinical and endoscopic findings, disease assessment, or for evaluation of mucosal healing. Moderate endoscopic lesions, defined as erythema and a few aphthous ulcers, were found in 32/71 patients (45%). Severe endoscopic lesions, defined as multiple and/or deep ulcers and/or stenosis without retention, were found in 12/71 patients (17%). There was a change in medication in 38/71 (54%) patients three months after CE, of which 27 initiated a new medication most commonly an immunomodulator or an anti- tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agent. Two patients required surgery. Seventy-five percent of patients with severe endoscopic lesions had a change in their management, compared to 53% with moderate lesions, and 4% with normal CE.

Long et al[29] performed a retrospective cohort study of 128 CE studies in established IBD patients between 2003 and 2009 at a tertiary referral center. Four capsule studies were excluded since they were retained in the stomach. Indications for CE included CD in 86, IBDU in 15, and pouchitis in 23 patients. The median duration of CD or IBDU was 6 years. The IPAA group had longer disease duration of 13.5 years. The majority of CD patients had either a few or multiple ulcerations with 22% having a normal CE. Sixty-two percent of the CD patients had a change in their medical management, defined as initiation or discontinuation of an IBD specific medication. Budesonide was the most common initiated medication with 40% of the CD patients starting a new medication. Eighty percent of the IBDU patients had a normal CE or mild erythema. Two thirds of these patients had a change in medical management with 40% initiating a new IBD specific medication, most commonly prednisone or budesonide. In addition, 44% of the IPAA patients had a normal CE or mild erythema with 57% of them starting a new medication. We suspect that given the disconnect between CE and treatment changes, the clinical symptoms or biomarkers played a more important role in management decisions. Capsule retention occurred in 15 of the CD patients, leading to either a small bowel resection or strictureplasty in 13% of the CD patients.

Overall, in patients with minimal findings on CE, 51% had a change in medical management compared to 73% of patients with severe findings. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, it is unclear if management changes were due to the CE findings or other factors. It is also unknown whether these medications changes impacted the disease course. In addition, only a small number of patients initiated immunosuppressants or biologics.

The effect of CE on the management of CD has been studied in the pediatric population as well. Min et al[30] evaluated whether CE will change management in the pediatric population. Indications for CE included active CD with poor growth in 50, IBDU in 16, and suspected IBD in 17 patients, respectively. Treatments and clinical outcomes were recorded before and one year after CE was performed. The overwhelming majority of patients with CD had abnormal CE findings (86%). Treatment escalation was required in 75% of patients, with the majority adding an anti-TNF agent, and 18% adding an immunomodulator. Follow up of these patients one year after capsule endoscopy showed statistically significant improvement in growth parameters, clinical indices, and laboratory markers. Given that the majority of patients requiring dose escalation had poor growth or active symptoms, it would appear that CE played a supportive role rather than a definitive role.

Flamant et al[31] studied the prevalence and significance of jejunal lesions on CE in established CD patients. CE studies from 108 CD patients were analyzed retrospectively, and 56% of these patients were found to have jejunal lesions (17% isolated to the jejunum). On multivariate analysis, jejunal lesions were the only factor associated with an increased risk of disease relapse over a median of two years with an adjusted hazard ration of 1.99 (95%CI: 1.10-3.61, P = 0.02). These data suggest that patients with proximal lesions may benefit from management top down strategy. This was demonstrated by Lazarev et al[32] who identified jejunal disease being associated with multiple abdominal surgeries.

While it does appear important to identify patients with jejunal disease given their higher risk for a complicated disease course, it’s not clear whether any particular imaging modality has the advantage.

Data for the use of CE to monitor disease or evaluate treatment efficacy in CD is limited. A small case series from Athens prospectively investigated the correlation of mucosal healing by CE with clinical response, defined as a CDAI drop of > 100 or a CDAI < 150[33]. Diagnosis of CD was confirmed histologically in 34 of the 40 patients. Patients included had active symptoms and the initial CE was done prior to any treatment. After treatment initiation, patients were followed up regularly until there was clinical improvement. Within one of day symptom improvement a second CE was performed to evaluate for mucosal healing. Three endoscopic variables were used for mucosal healing; number of aphthous ulcers, number of large ulcers, and the period of time that any endoscopic lesion was visible. The number of large ulcers significantly decreased, while the number of aphthous ulcers remained unchanged. Because only one of the three markers improved, the authors concluded that clinical response did not correlate with mucosal healing. A major limitation of this study was the significant heterogeneity among treatments, which were chosen by the managing physicians. Only 6 patients received immunomodulators and steroids or anti-TNF agents, and they had the most significant endoscopic improvement.

In an abstract presented at the 2013 Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America meeting, Shafran et al[34] retrospectively evaluated whether mucosal healing defined by CE was critical in management decisions. Twenty-three patients were analyzed of which 17 achieved mucosal healing, determined by a single expert physician reader along with a Lewis score if available. Of the 17 patients with mucosal healing, 15 remained in clinical remission on their current treatment plan. In the 6 patients who did not achieve mucosal healing, four patients achieved clinical remission with changes in medications, 1 patient required surgery, and 1 patient entered a clinical trial.

Larger prospective trials are needed to confirm the utility of serial CEs to assess mucosal healing in patients with nonstricturing isolated small bowel CD. It will be important to identify these patients early as they may benefit from more intensive treatments, but it is unclear if CE would be superior to radiology.

Capsule retention is the greatest concern in patients with IBD. Adding to this concern is that the majority of patients do not visualize the capsule passing in the stool. In a systematic review involving 227 articles with 22840 capsule studies, the overall pooled retention rate was 1.4%. The pooled retention rate for established CD was 2.6%[3].

Capsule retention does not necessarily require surgical intervention. Some patients with retained capsules are asymptomatic, while others can be managed medically with steroids or anti-TNF agents, to allow for passage through an inflammatory stricture. Other cases can be managed endoscopically with retrieval accomplished by deep enteroscopy or colonoscopy. Surgery with resection of the strictured segment or strictureplasty is sometimes required.

Although capsule retention should be avoided, some believe that retention leads to the appropriate diagnosis and management by allowing for localization of the culprit lesion. In a study by Cheifetz et al[35] CE was used in 19 patients with suspected small bowel obstruction based on symptoms or imaging. The capsule was retained in four patients proximal to the stricture and they all underwent elective surgery. Since the capsule was not lodged in the stricture, emergent surgery was not indicated in any of these patients. The operative findings of these four patients were deep ulceration and stricture in midjejunum, a jejunal anastomotic stricture, focal ulcerated stricture in the jejunum, and an ileal stricture.

Given imaging has developed the Agile patency capsule, which is the same size as Pillcam SB. The capsule is composed of lactose and barium with an impermeable membrane that disintegrates in less than 30 h. It contains a radiofrequency identification chip, which can be detected by a scanner if retained in the small bowel.

Herrerias et al[36] evaluated the Agile patency capsule in 106 patients with known intestinal strictures. In this series, 13 patients had obstructive symptoms that were possibly or probably secondary to the Agile patency capsule. The Agile patency system is recommended when there is a suspicion for an intestinal stricture or obstruction to anticipate the subsequent safe passage of CE.

A limitation of CE and of many of the studies reviewed in this article is interobserver variability. Two main scoring systems have been developed to address this problem. The Lewis Score quantifies mucosal change and disease extent by assessing villous appearance, presence of ulcers and stenosis over each segment of small bowel[37]. In 2008, Gal et al[38] developed the capsule endoscopy crohn’s disease activity index which evaluates inflammation, extent of disease, and presence of stricture, all graded on a numeric scale with the small bowel divided into proximal and distal halves. The Lewis score has been made more accessible as it was incorporated into the PillCam software (Given, Rapid Reader). Nevertheless, neither scoring system is utilized routinely in clinical practice. Furthermore, there is no definitive correlation between the score and the patient’s clinical status or CDAI[11]. Although scoring systems may be useful for longitudinal monitoring of CD, they have not been validated for this purpose.

Multiple variables need to be taken into account when deciding which imaging test is best to the study the small bowel in patients with established or suspected CD. The availability of CTE is institution dependant, and there are concerns about cumulative ionizing radiation exposure in CD patients[39]. MRE avoids radiation and allows for extraluminal imaging. It is often our first test of choice in newly diagnosed CD patients. However, CE is performed by gastroenterologists and seems to have higher sensitivity for mucosal lesions compared to cross sectional imaging.

We use CE in post-operative evaluation when the neoterminal ileum cannot be intubated or in patients with symptoms, anemia, or biomarker elevation in the setting of a normal colonoscopy. Clinically, we can confirm the data of Efthymiou et al[33], when colonic mucosal healing did not result in correction of iron deficiency anemia and CE confirmed ongoing active inflammation (aphthous ulcers) in the small bowel. CE may be the preferred option in pediatric patients with nonstricturing disease as it seems to result in management changes that are more significant than in the adult population. Increasingly mucosal healing has become the preferred endpoint of medical management and CE, along with biomarkers and cross sectional imaging, will play an important role in noninvasive disease monitoring of the small bowel.

P- Reviewer: Maehata Y, Oka S, Teshima CW S- Editor: Ding Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Steinhardt HJ, Loeschke K, Kasper H, Holtermüller KH, Schäfer H. European Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study (ECCDS): clinical features and natural history. Digestion. 1985;31:97-108. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Mow WS, Lo SK, Targan SR, Dubinsky MC, Treyzon L, Abreu-Martin MT, Papadakis KA, Vasiliauskas EA. Initial experience with wireless capsule enteroscopy in the diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:31-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liao Z, Gao R, Xu C, Li ZS. Indications and detection, completion, and retention rates of small-bowel capsule endoscopy: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:280-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 561] [Cited by in RCA: 476] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Goldstein JL, Eisen GM, Lewis B, Gralnek IM, Zlotnick S, Fort JG. Video capsule endoscopy to prospectively assess small bowel injury with celecoxib, naproxen plus omeprazole, and placebo. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:133-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 499] [Cited by in RCA: 451] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Albert JG, Martiny F, Krummenerl A, Stock K, Lesske J, Göbel CM, Lotterer E, Nietsch HH, Behrmann C, Fleig WE. Diagnosis of small bowel Crohn’s disease: a prospective comparison of capsule endoscopy with magnetic resonance imaging and fluoroscopic enteroclysis. Gut. 2005;54:1721-1727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hara AK, Leighton JA, Heigh RI, Sharma VK, Silva AC, De Petris G, Hentz JG, Fleischer DE. Crohn disease of the small bowel: preliminary comparison among CT enterography, capsule endoscopy, small-bowel follow-through, and ileoscopy. Radiology. 2006;238:128-134. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Solem CA, Loftus EV, Fletcher JG, Baron TH, Gostout CJ, Petersen BT, Tremaine WJ, Egan LJ, Faubion WA, Schroeder KW. Small-bowel imaging in Crohn's disease: a prospective, blinded, 4-way comparison trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:255-266. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Dubcenco E, Jeejeebhoy KN, Petroniene R, Tang SJ, Zalev AH, Gardiner GW, Baker JP. Capsule endoscopy findings in patients with established and suspected small-bowel Crohn’s disease: correlation with radiologic, endoscopic, and histologic findings. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:538-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dionisio PM, Gurudu SR, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, Fleischer DE, Hara AK, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK. Capsule endoscopy has a significantly higher diagnostic yield in patients with suspected and established small-bowel Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1240-128; quiz 1249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 10. | Jensen MD, Nathan T, Rafaelsen SR, Kjeldsen J. Diagnostic accuracy of capsule endoscopy for small bowel Crohn’s disease is superior to that of MR enterography or CT enterography. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:124-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 11. | Swaminath A, Legnani P, Kornbluth A. Video capsule endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease: past, present, and future redux. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1254-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Casciani E, Masselli G, Di Nardo G, Polettini E, Bertini L, Oliva S, Floriani I, Cucchiara S, Gualdi G. MR enterography versus capsule endoscopy in paediatric patients with suspected Crohn’s disease. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:823-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Levesque BG, Cipriano LE, Chang SL, Lee KK, Owens DK, Garber AM. Cost effectiveness of alternative imaging strategies for the diagnosis of small-bowel Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:261-27, 261-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gerson LB. Use and misuse of small bowel video capsule endoscopy in clinical practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1224-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A:5A-36A. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Stewénius J, Adnerhill I, Ekelund G, Florén CH, Fork FT, Janzon L, Lindström C, Mars I, Nyman M, Rosengren JE. Ulcerative colitis and indeterminate colitis in the city of Malmö, Sweden. A 25-year incidence study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:38-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Price AB. Overlap in the spectrum of non-specific inflammatory bowel disease--’colitis indeterminate’. J Clin Pathol. 1978;31:567-577. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Stewénius J, Adnerhill I, Ekelund GR, Florén CH, Fork FT, Janzon L, Lindström C, Ogren M. Risk of relapse in new cases of ulcerative colitis and indeterminate colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1019-1025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Maunoury V, Savoye G, Bourreille A, Bouhnik Y, Jarry M, Sacher-Huvelin S, Ben Soussan E, Lerebours E, Galmiche JP, Colombel JF. Value of wireless capsule endoscopy in patients with indeterminate colitis (inflammatory bowel disease type unclassified). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:152-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mehdizadeh S, Chen G, Enayati PJ, Cheng DW, Han NJ, Shaye OA, Ippoliti A, Vasiliauskas EA, Lo SK, Papadakis KA. Diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy in ulcerative colitis and inflammatory bowel disease of unclassified type (IBDU). Endoscopy. 2008;40:30-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Murrell Z, Vasiliauskas E, Melmed G, Lo S, Targan S, Fleshner P. Preoperative wireless capsule endoscopy does not predict outcome after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:293-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sachar DB. The problem of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease. Med Clin North Am. 1990;74:183-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Olaison G, Smedh K, Sjödahl R. Natural course of Crohn’s disease after ileocolic resection: endoscopically visualised ileal ulcers preceding symptoms. Gut. 1992;33:331-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 370] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Beyls J, Kerremans R, Hiele M. Predictability of the postoperative course of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:956-963. [PubMed] |

| 25. | De Cruz P, Kamm MA, Prideaux L, Allen PB, Desmond PV. Postoperative recurrent luminal Crohn’s disease: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:758-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bourreille A, Jarry M, D’Halluin PN, Ben-Soussan E, Maunoury V, Bulois P, Sacher-Huvelin S, Vahedy K, Lerebours E, Heresbach D. Wireless capsule endoscopy versus ileocolonoscopy for the diagnosis of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease: a prospective study. Gut. 2006;55:978-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pons Beltrán V, Nos P, Bastida G, Beltrán B, Argüello L, Aguas M, Rubín A, Pertejo V, Sala T. Evaluation of postsurgical recurrence in Crohn’s disease: a new indication for capsule endoscopy? Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:533-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Dussault C, Gower-Rousseau C, Salleron J, Vernier-Massouille G, Branche J, Colombel JF, Maunoury V. Small bowel capsule endoscopy for management of Crohn’s disease: a retrospective tertiary care centre experience. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:558-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Long MD, Barnes E, Isaacs K, Morgan D, Herfarth HH. Impact of capsule endoscopy on management of inflammatory bowel disease: a single tertiary care center experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1855-1862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Min SB, Le-Carlson M, Singh N, Nylund CM, Gebbia J, Haas K, Lo S, Mann N, Melmed GY, Rabizadeh S. Video capsule endoscopy impacts decision making in pediatric IBD: a single tertiary care center experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2139-2145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Flamant M, Trang C, Maillard O, Sacher-Huvelin S, Le Rhun M, Galmiche JP, Bourreille A. The prevalence and outcome of jejunal lesions visualized by small bowel capsule endoscopy in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1390-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lazarev M, Huang C, Bitton A, Cho JH, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Proctor DD, Regueiro M, Rioux JD, Schumm PP. Relationship between proximal Crohn’s disease location and disease behavior and surgery: a cross-sectional study of the IBD Genetics Consortium. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:106-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Efthymiou A, Viazis N, Mantzaris G, Papadimitriou N, Tzourmakliotis D, Raptis S, Karamanolis DG. Does clinical response correlate with mucosal healing in patients with Crohn’s disease of the small bowel? A prospective, case-series study using wireless capsule endoscopy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1542-1547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 34. | Shafran I, Burgunder P, Kwa M. The use of serial wireless capsule endoscopy in treatment decisions to improve outcomes in small bowel Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:S58. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 35. | Cheifetz AS, Lewis BS. Capsule endoscopy retention: is it a complication? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:688-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Herrerias JM, Leighton JA, Costamagna G, Infantolino A, Eliakim R, Fischer D, Rubin DT, Manten HD, Scapa E, Morgan DR. Agile patency system eliminates risk of capsule retention in patients with known intestinal strictures who undergo capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:902-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Gralnek IM, Defranchis R, Seidman E, Leighton JA, Legnani P, Lewis BS. Development of a capsule endoscopy scoring index for small bowel mucosal inflammatory change. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:146-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Gal E, Geller A, Fraser G, Levi Z, Niv Y. Assessment and validation of the new capsule endoscopy Crohn’s disease activity index (CECDAI). Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:1933-1937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Chatu S, Subramanian V, Pollok RC. Meta-analysis: diagnostic medical radiation exposure in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:529-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |