Published online Aug 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i32.11326

Revised: March 11, 2014

Accepted: May 23, 2014

Published online: August 28, 2014

Processing time: 224 Days and 7.7 Hours

AIM: To examine hospitalization rates for variceal hemorrhage and relation to cause of cirrhosis during an era of increased cirrhosis prevalence.

METHODS: We performed a retrospective review of patients with cirrhosis and gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage who were admitted to a tertiary care referral center from 1998 to 2009. Subjects were classified according to the etiology of their liver disease: alcoholic cirrhosis and non-alcoholic cirrhosis. Rates of hospitalization for variceal bleeding were determined. Data were also collected on total hospital admissions per year and cirrhosis-related admissions per year over the same time period. These data were then compared and analyzed for trends in admission rates.

RESULTS: Hospitalizations for cirrhosis significantly increased from 611 per 100000 admissions in 1998-2001 to 1232 per 100000 admissions in 2006-9 (P value for trend < 0.0001). This increase was seen in admissions for both alcoholic and non-alcoholic cirrhosis (P values for trend < 0.001 and < 0.0001 respectively). During the same time period, there were 243 admissions for gastroesophageal variceal bleeding (68% male, mean age 54.3 years, 62% alcoholic cirrhosis). Hospitalizations for gastroesophageal variceal bleeding significantly decreased from 96.6 per 100000 admissions for the time period 1998-2001 to 70.6 per 100000 admissions for the time period 2006-2009 (P value for trend = 0.01). There were significant reductions in variceal hemorrhage from non-alcoholic cirrhosis (41.6 per 100000 admissions in 1998-2001 to 19.7 per 100000 admissions in 2006-2009, P value for trend = 0.007).

CONCLUSION: Hospitalizations for variceal hemorrhage have decreased, most notably in patients with non-alcoholic cirrhosis, and this may reflect broader use of strategies to prevent bleeding.

Core tip: Strategies to prevent gastroesophageal variceal bleeding, a morbid complication of cirrhosis, have been largely unchanged for 15 years. With the rising burden of cirrhosis over this time, it might be predicted that there would be a parallel increase in hospitalization rates for this complication. The findings from this study show that hospitalization rates for variceal bleeding are in fact decreasing, specifically in non-alcoholic cirrhosis. This raises the possibility that reductions in hospital admissions for variceal bleeding are attributable to more widespread use of prophylactic measures, and that expansion of these measures in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis could further reduce hospitalizations.

- Citation: Lim N, Desarno MJ, Lidofsky SD, Ganguly E. Hospitalization for variceal hemorrhage in an era with more prevalent cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(32): 11326-11332

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i32/11326.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i32.11326

Chronic liver disease is currently the twelfth leading cause of death in the United States; most liver disease-related deaths are the result of complications of cirrhosis. In particular, in 2007, 14406 and 14759 deaths were attributable to alcoholic and non-alcoholic cirrhosis, respectively. This represented an increase of 3.4% since 2006[1].

Development of gastroesophageal varices is a serious complication of cirrhosis. At the time of diagnosis of cirrhosis, esophageal varices are present in almost half of all patients and develop at a rate of approximately 7% per year[2]. The 1-year rate of a first variceal hemorrhage is approximately 12%. The short term mortality rate associated with variceal hemorrhage is over 15% and can be as high as 30% in patients with decompensated (Child’s Class C) cirrhosis[2]. Thus, prevention of variceal bleeding is a critical goal in the management of cirrhosis. The use of nonselective beta-adrenergic receptor blockade and endoscopic band ligation for prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage emerged in the 1980s and mid-1990s, respectively[3-7]. These strategies have been associated with a decline in mortality related to esophageal hemorrhage[8].

During this same era, however, cirrhosis and its complications have become significantly more prevalent, with increases from 18% to over 50%[9,10]. In the face of this rise in the burden of cirrhosis, it is therefore unknown whether the use of currently available prophylactic strategies would offset a parallel expected increase in the rate of variceal hemorrhage. Insights into this issue come from an analysis of a large nationwide hospital discharge database[11]. In this study, the hospitalization rate for bleeding varices increased from 1988 to 1996 and then fell between 1996 and 2002. Although these findings suggested that the changes reflected advances in prophylactic strategies, the data were obtained over a time period when such strategies were evolving.

Strategies to prevent variceal bleeding were codified in the form of practice guidelines in 1997[12] and no new strategies have emerged since. Thus, if an ongoing decrease in the incidence of variceal bleeding was observed in a more recent era, the expectation is that this would reflect increased utilization of effective prophylactic strategies. To test this, we assessed the rates of hospital admissions for variceal hemorrhage during the time period when prophylactic strategies for prevention of variceal hemorrhage had been well established (1998 to 2009). In addition, to our knowledge, no study has investigated whether the etiology of cirrhosis (alcohol-related or non-alcohol-related) has an impact on the rate of variceal hemorrhage. A secondary aim of the study was therefore to determine if the etiology of cirrhosis (alcohol-related vs non-alcohol related) correlated with rates of variceal hemorrhage in this era.

This was a retrospective, cross-sectional review for all hospital admissions for gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage to an intensive care unit at a tertiary referral center (University of Vermont/Fletcher Allen Health Care) between 1998 and 2009. Patients were initially identified based on International Classification of Disease (ICD-9) codes for upper gastrointestinal bleeding: esophageal varices with bleeding (456.0); esophageal varices in disease classified elsewhere with bleeding (456.20); hematemesis (578.0); blood in stool/melena (578.1) and hemorrhage of gastrointestinal tract, unspecified (578.9).

Bleeding secondary to variceal hemorrhage was confirmed by review of the inpatient hospital record and endoscopy database. Bleeding was attributed to varices if one of the following criteria was met: (1) actively bleeding varices visualized on endoscopy; (2) varices identified on endoscopy with stigmata of recent hemorrhage; or (3) clinical presentation consistent with upper gastrointestinal bleed (melena or hematemesis) and presence of varices on endoscopy with no other etiology for bleeding identified. Eligibility criteria for further inclusion were a diagnosis of cirrhosis and age at least 18 years.

Demographic and outcomes data were analyzed for the entire cohort, and subgroup analysis was performed according to the etiology of cirrhosis (alcoholic versus non-alcoholic). Patients admitted with their first variceal bleed were defined as “Index Bleeds”. Patients admitted with their second or greater episode of variceal bleeding were defined as “Rebleeds”. A model of end stage liver disease (MELD) score was calculated[13], where possible, when same day laboratory data were available.

During the same time period, data were collected on total hospital admissions per year and cirrhosis-related admissions. Cirrhosis-related admissions were categorized further by etiology using ICD-9 hospital billing codes: alcoholic cirrhosis of liver (571.2) and cirrhosis of liver NOS (571.5). Patients younger than 18 years old were excluded.

Variceal bleeding data were then directly compared to cirrhosis-related and total admission data and evaluated for trends.

Data on placement of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) were obtained using procedure volumes reports generated using the radiology information system for exam codes: SPTIPS, SPHEPATVEN and SPHEPATVNWO.

Using Pearson’s χ2 test for two proportions, we calculated that a sample size of n = 129 would result in 90% statistical power to detect a 15% change in variceal bleed % (at an alpha level of 0.05).

For analyses of linear trends over time for numeric variables, linear regression analysis was employed to calculate Pearson correlation coefficients, and to determine statistical significance of trends. A “P value” of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

For analyses of linear trends over time for categorical variables (percentage positive responses of total for dichotomous variables), logistic regression analysis and/or analysis of two-way contingency tables (for Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel nonzero correlation statistics) were done. Using these methods, statistical significance of linear trends were determined, along with corresponding odds rates. A “P value” of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

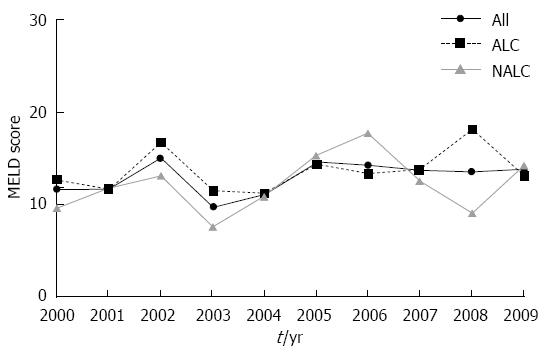

A total of 1719 inpatient admissions were identified with upper gastrointestinal bleeding based on hospital discharge diagnosis. After review of the inpatient records, 243 admissions satisfied the criteria for bleeding attributable to gastroesophageal varices for the period 1998-2009 (Table 1). Approximately half of these were index bleeds. The mean age was 54.33 years, approximately two thirds of patients were male, and nearly all were white. Cirrhosis was attributed to alcohol in 62% of the patients. When compared to non-alcoholic cirrhotics, the patients with alcohol-related variceal bleeding were significantly younger and more likely to be male. The average MELD score could be calculated for the years 2000-2009 and did not statistically change during this period nor did the average MELD for the cohort change over time (P value for trend = 0.20, Pearson correlation coefficient 0.44) (Figure 1). The average MELD score did not differ statistically between the two groups (P = 0.27).

| Overall | ETOH | Non-ETOH | P value | |

| No. ICU admissions | 243 | 151 | 92 | |

| Mean age | 54.33 | 52.92 | 58.25 | 0.002 |

| Male sex | 165 (67.9) | 119 | 46 | 0.003 |

| White ethnicity | 235 (96.7) | 147 | 88 | 0.04 |

| Nonselective beta-blocker | 82 (33.7) | 45 | 37 | 0.51 |

| Index bleed | 128 (52.6) | 78 | 50 | 0.07 |

| Deaths | 43 (17.6) | 22 | 21 | 0.88 |

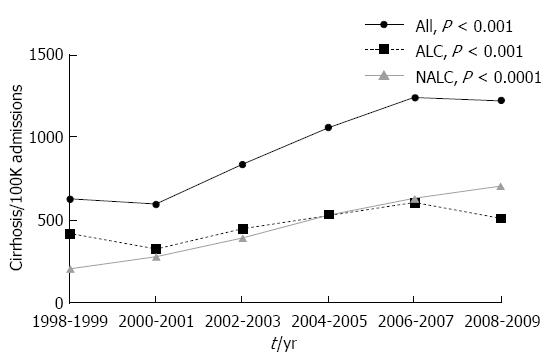

During the study period, total admissions for cirrhosis increased by more than 100% (Figure 2), from 611 per 100000 admissions in 1998-2001 to 1232 per 100000 admissions in 2006-2009 (P value for trend ≤ 0.0001). Increases were observed regardless of etiology of cirrhosis. Admissions for alcoholic cirrhosis increased 52% during the study period, from 369 per 100000 admissions in 1998-2001 to 560 per 100000 admissions in 2006-2009 (P value for trend ≤ 0.001). Admissions for non-alcoholic cirrhosis increased 175%, from 244 per 100000 admissions in 1998-2001 to 672 per 100000 admissions in 2006-2009 (P value for trend ≤ 0.0001).

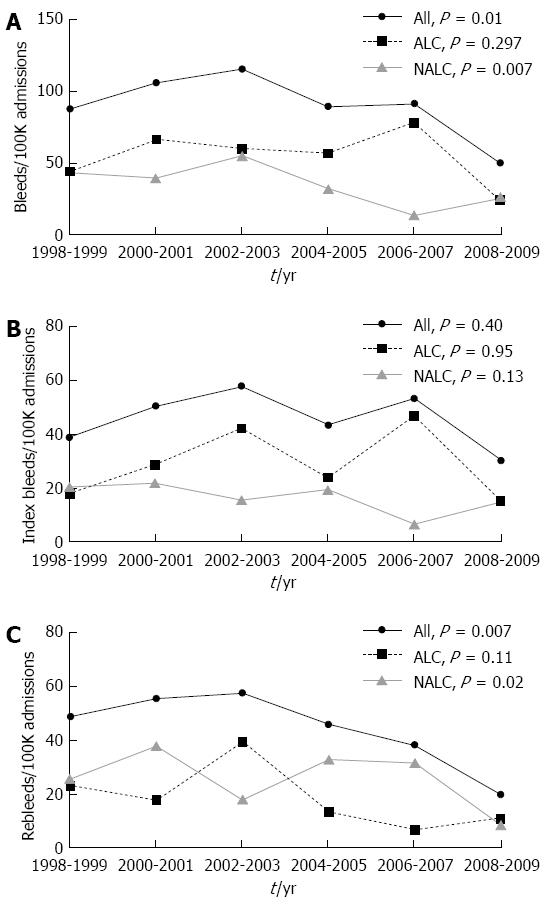

As shown in Figure 3A, the overall hospitalization rate for variceal bleeding decreased significantly from 96.6 per 100000 admissions in 1998-2001 to 70.6 per 100000 admissions from 2006-2009 (P value for trend = 0.01). When analyzed according to etiology, the hospitalization rate for variceal hemorrhage related to alcoholic cirrhosis did not statistically decrease during the study period (55 per 100000 admissions in 1998-2001, 50.9 per 100000 admissions in 2006-2009; P value for trend = 0.297). By contrast, hospitalization for variceal hemorrhage from non-alcoholic cirrhosis decreased significantly from 41.6 per 100000 admissions in 1998-2001 to 19.7 per 100000 admissions in 2006-2009 (P value for trend = 0.007).

As shown in Figure 3B, hospitalizations for index bleeding did not significantly change in either group (alcoholic cirrhosis: 23.48 per 100000 admissions in 1998-2001 to 30.91 per 100000 admissions in 2006-2009, P value for trend = 0.95, OR = 1.00; non-alcoholic cirrhosis: 29.14 per 100000 admissions in 1998-2001 to 10.92 per 100000 admissions in 2006-2009, P value for trend = 0.13, OR = 0.94).

Admission trends differed when there was a history of previous variceal hemorrhage. Hospitalizations for variceal rebleeding decreased for the overall study population (Figure 3C), from 51.85 per 100000 admissions in 1998-2001 to 28.72 per 100000 admissions in 2006-2009 (P value for trend = 0.007, OR = 0.93). This decrease remained significant after controlling for age (P value for trend = 0.01, OR = 0.93), and was seen specifically among patients with non-alcoholic cirrhosis (P value for trend = 0.02, OR = 0.91) but not in the alcoholic cirrhosis group (P value for trend = 0.11, OR = 0.95).

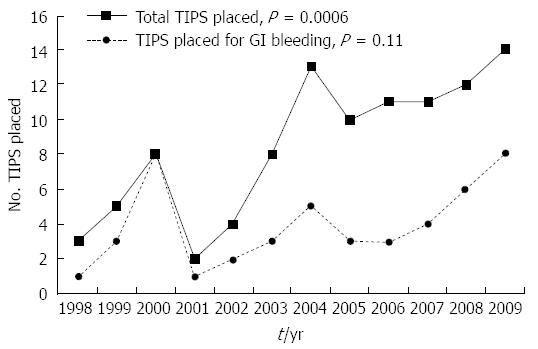

In parallel with the increased number of hospitalizations for cirrhosis, there was a significant increase in the number TIPS placements (Figure 4, P value for trend = 0.0006, Pearson correlation coefficient 0.84). A total of 101 TIPS were placed for all indications between 1998 to 2009, but the minority (47) were placed for portal hypertensive gastrointestinal bleeding. As can be shown in Figure 4, the number of TIPS placed for this indication fluctuated over the study period, but did not statistically significantly increase (P value for trend = 0.11, Pearson correlation coefficient 0.48).

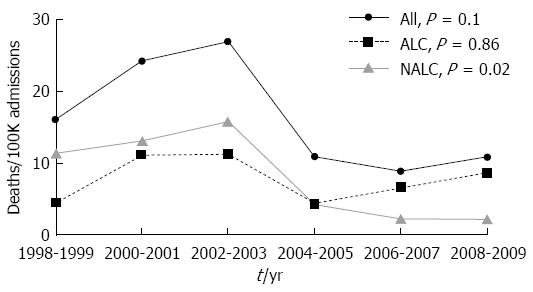

Hospital deaths associated with variceal bleeding decreased significantly during the study period (Figure 5), from 20.09 per 100000 admissions in 1998-2001 to 9.83 per 100000 admissions in 2006-2009 (P value for trend = 0.04, OR = 0.914). This decrease was not statistically significant after controlling for age (P value for trend = 0.1). However, when controlling for age, death from variceal bleeding in the non-alcoholic cirrhotic group significantly decreased from 12.26 per 100000 admissions in 1998-2001 to 2.18 per 100000 admissions in 2006-2009 (P value for trend = 0.02, OR = 0.83); by contrast variceal hemorrhage-related death in the group with alcoholic cirrhosis did not significantly change (7.83 per 100000 admissions in 1998-2001 to 7.65 per 100000 admissions in 2006-2009, P value for trend = 0.86, OR = 0.99). Length of stay decreased significantly for the alcoholic cirrhosis bleeds (10.47 d in 1998-2001 to 5.71 d in 2006-2009), but not for the non-alcoholic cirrhosis bleeds (10.45 d in 1998-2001 to 7.39 d in 2006-2009), or the overall study population (10.12 d in 1998-2001 to 6.32 d in 2006-2009) (P value for trend = 0.03, 0.48, and 0.13; Pearson correlation coefficient = -0.062, -0.23, and -0.45 respectively).

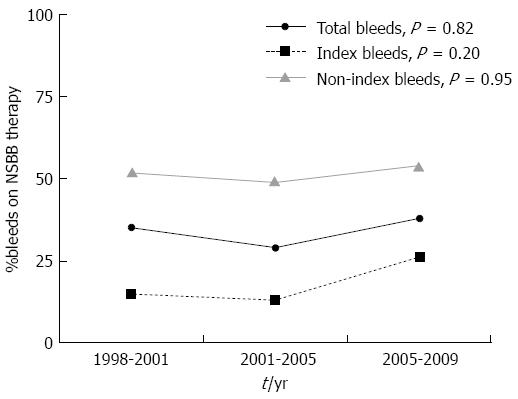

During the study period, 82 of 243 (33%) variceal bleeds occurred in patients taking non-selective beta-blockers (carvedilol, nadolol or propanolol)(NSBBs). Among patients with index bleeds, 17.7% were taking NSBBs, and this was significantly lower than the proportion of patients with re-bleeds (51.3%) who were taking NSBBs (P < 0.0001) (Figure 6). NSBB use did not change over time in the study cohort (35% of patients in 1998-2001 vs 38% patients in 2006-2009, P value for trend = 0.82). There was no significant trend in NSBB use over time in either the index-bleed or non-index bleed subgroups (P value for trend = 0.20 and 0.95 respectively).

This study has evaluated trends in hospitalizations to an intensive care unit for variceal bleeding during a period when pharmacological and endoscopic therapies for prevention of this problem were well-established and largely unchanged, as supported by published practice guidelines[12,14]. Our findings show that despite increasing hospitalization rates for cirrhosis of all causes, hospitalization rates for variceal bleeding have actually decreased, specifically in patients with cirrhosis from non-alcoholic etiologies.

Our observations extend those of previous work, which showed an increase in admissions from variceal bleeding from 10.9 to 12.4 per 100000 between 1988-1990 and 1994-1996, and then a decrease to 10.6 per 100000 in 2000-2002. During this entire period, strategies to prevent variceal hemorrhage were still evolving, and the prevalence of cirrhosis was increasing. Interactions between these two factors may have accounted for the changing incidence in hospitalizations. As shown in the present study, there has been a continued decrease in admissions for variceal bleeding, between 1998-2001 and 2006-2009, an era in which hospitalizations among cirrhotic individuals has continued to increase. The lack of an expected increase in variceal bleeding raises the possibility that enhanced application of prophylactic therapies may be offsetting the increasing burden of cirrhosis and thus the pool of patients at risk for bleeding from gastroesophageal varices. This is supported by published surveys, which showed increased adoption of such therapies by gastroenterologists in response to publication of practice guidelines[15]. Since our study did not show that index bleeding has decreased, it may be that these strategies have been mainly effective in the secondary prevention of variceal bleeding, at least among patients with non-alcoholic cirrhosis.

An alternative explanation for the reduction seen in variceal rebleeding could be increased placement of TIPS, which has evolved to become the standard of care in refractory variceal bleeding[14,16-21]. Whilst we observed an increase in TIPS placement over the study period, the overall number of TIPS placed was small in comparison to the cirrhotic population at risk for variceal hemorrhage. Thus, other factors are likely to be more important contributors to changing trends in hospitalizations for variceal bleeding.

There was a low rate of NSBB use in our cohort, particularly among those with index bleeds. Several factors may account for this. Among index bleeders, it is possible that not all patients underwent screening endoscopy prior to the episode of variceal bleeding, that some patients were intolerant of these agents, or that some did not adhere to medical recommendations. The significantly higher rate of NSBB use in rebleeding patients may be explained by more uniform adoption of consensus guidelines for secondary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage, but problems related to drug tolerance and patient adherence may have resulted in less than uniform drug usage. Our study was not designed to address these issues, but this would be appealing to assess in the future.

It is also notable that while admissions for variceal bleeding from non-alcohol-related variceal bleeding at our institution have significantly decreased, those from alcohol-related cirrhosis have been stable. One possible explanation for the difference in variceal bleeding rates between the two groups is that in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis, alcohol ingestion increases portal pressure[22], a major driving force for variceal hemorrhage. Alternatively, patients with alcoholic cirrhosis may not have similar access, in comparison with patient with nonalcoholic cirrhosis, to beneficial prophylactic measures. Since active alcoholism may negatively affect adherence to prescribed medications[23], it is possible that this may translate among patients with alcoholic cirrhosis into decreased utilization of measures to prevent variceal bleeding. This concept is further supported by our findings that rebleeding from varices has decreased only in non-alcoholic cirrhosis. Efforts to improve delivery and utilization of prophylactic therapies for variceal bleeding in patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis may result in similar reductions of bleeding.

A second major finding of this study is that in-hospital mortality associated with gastroesophageal variceal bleeding has decreased. This extends a decrease in mortality that was initially observed 30 years ago, which paralleled the emergence of robust targeted pharmacologic, endoscopic, and interventional radiologic treatments for control of variceal hemorrhage. Although such decreases were initially observed in clinical trials, they have been confirmed in larger populations, most recently in an analysis of a nationwide hospital database between 1988 and 2004[24]. It is striking that we have observed a continued decrease in mortality over a more recent time period, an era in which targeted therapies for variceal bleeding have not changed. The observed decrease in mortality is unlikely to be related to the prevalence of decompensated liver disease (a known risk factor for adverse outcomes in variceal hemorrhage[2]) in our patient cohort as the mean MELD score, an index of liver disease severity[13], did not change during the study period. It is tempting to speculate that the decrease in in-hospital mortality reflected changes in management not directly targeted to varices per se, such as administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics to prevent adverse sequelae (e.g., spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, bacteremia) of variceal bleeding, which have been shown to decrease mortality[14,25]. Although this study was not designed to look at infectious outcomes, it is interesting to note that age-adjusted mortality decreases were seen in the non-alcoholic cirrhotic group but not in patients with a history of alcohol use, a known risk factor for increased mortality in critical illness accompanied by infections[26,27]. Whether the etiology of cirrhosis, and in particular, ongoing alcohol consumption influences the effectiveness of prophylactic antibiotics on morbidity and mortality of variceal hemorrhage is an intriguing question for future study.

Two additional points merit comment. First, because our study used ICD-9 coding data to identify patients, it is possible that patients hospitalized for variceal bleeding were missed by our analysis. However, this is unlikely, since the endoscopy database was examined in parallel, which allowed us to capture patients that would otherwise have been overlooked. Second, our study was performed in a single center in a predominantly rural region with limited ethnic diversity. As of 2010, 95.2% of the population of Vermont was reported as of white ethnicity[28]. Thus, it would be important to test whether our findings extend to other populations.

Collectively, our findings show that despite a large increase in admissions for cirrhosis for over a decade, hospitalizations and in-hospital mortality for variceal bleeding are decreasing, specifically in patients with non-alcoholic cirrhosis. This suggests that current management strategies for the prevention and treatment of variceal bleeding are having a positive impact on these outcomes. Since a decrease in hospitalizations was not observed for patients with index bleeds, this raises the possibility that cirrhosis was not recognized prior to the bleeding episode or that programs to diagnose and treat varices in asymptomatic cirrhotic patients have not been optimized. Improving access to preventative measures in such patients, and in particular, those with alcoholic cirrhosis, could potentially further reduce future hospitalizations for variceal hemorrhage.

The prevalence of cirrhosis, a consequence of long-term liver injury, has been increasing. Cirrhosis often leads to portal hypertension, and complications from portal hypertension, such as gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage, result in significant morbidity and mortality. These adverse outcomes have been improved by prophylactic measures established well over 15 years ago, including endoscopic variceal ligation and non-selective beta-blockers, but treatment advances have been limited more recently. It is unknown how this limitation has influenced hospitalization trends during this more recent era.

In analysis of tends for gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage in an era in which preventative strategies were improving, prior work has shown that there has been a reduction in hospitalizations for this complication. In this study, the authors have sought to examine whether this trend has been maintained during an era in which no new preventative strategies have emerged, and whether such trends have been influenced by the etiology of cirrhosis.

In contrast to prior work, which analyzed trends for gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage during an era of improving prophylactic strategies, the present study confines the analysis to a more recent era, in which such strategies have not improved further. The results show that hospitalizations for gastroesophageal bleeding have been decreasing, particularly in cirrhosis of non-alcoholic etiology. This raises the possibility that enhanced application of prophylactic therapies has offset the increasing burden of cirrhosis.

These findings suggest that in the absence of new prophylactic strategies against gastroesophageal bleeding, future reductions in hospitalizations for this complication of cirrhosis are likely to come from increased adherence to existing preventative programs. The authors suggest that new research be devoted to quality improvement in this area.

Cirrhosis is a disorder, in response to chronic injury of extensive scar formation and distortion of blood flow within the liver. In cirrhosis, progressive resistance to liver blood flow increases pressure in the portal vein, the major blood vessel that supplies the liver. This condition, portal hypertension, can lead to several complications, including formation of gastroesophageal varices, engorged veins that are present beneath the interior surface of the esophagus and stomach. When the pressure in the portal vein increases above a critical value, bleeding from gastroesophageal varices can occur. Two strategies have been used successfully to prevent this problem, endoscopic techniques that directly apply elastic bands to obliterate esophageal varices, and medications (non-selective beta-blockers) that lower the pressure in the portal vein.

This manuscript evaluates the hospitalization trends for variceal bleeding during a period when the prevalence of cirrhosis has increased. The study is well designed, all the section (from abstract to conclusions) are well written, and the topic is interesting for the readers.

P- Reviewer: Stanciu C, Weber FH S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Xu J, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Tejada-Vera B; Division of Vital Statistics. Deaths: Final data for 2007. Nat Vital Stat Rep. 2010;58:1-136. |

| 2. | Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J. Management of varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:823-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 639] [Cited by in RCA: 638] [Article Influence: 42.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pascal JP, Cales P. Propranolol in the prevention of first upper gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:856-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Poynard T, Calès P, Pasta L, Ideo G, Pascal JP, Pagliaro L, Lebrec D. Beta-adrenergic-antagonist drugs in the prevention of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis and esophageal varices. An analysis of data and prognostic factors in 589 patients from four randomized clinical trials. Franco-Italian Multicenter Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1532-1538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Lin CK, Hsu PI, Chiang HT. Prophylactic banding ligation of high-risk esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis: a prospective, randomized trial. J Hepatol. 1999;31:451-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lay CS, Tsai YT, Teg CY, Shyu WS, Guo WS, Wu KL, Lo KJ. Endoscopic variceal ligation in prophylaxis of first variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients with high-risk esophageal varices. Hepatology. 1997;25:1346-1350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sarin SK, Guptan RK, Jain AK, Sundaram KR. A randomized controlled trial of endoscopic variceal band ligation for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:337-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Imperiale TF, Chalasani N. A meta-analysis of endoscopic variceal ligation for primary prophylaxis of esophageal variceal bleeding. Hepatology. 2001;33:802-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kanwal F, Hoang T, Kramer JR, Asch SM, Goetz MB, Zeringue A, Richardson P, El-Serag HB. Increasing prevalence of HCC and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1182-1188.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Talwalkar JA. Time trends in hospitalization and discharge status for cirrhosis and portal hypertension in the United States. Hepatology. 2010;52:1862; author reply 1863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jamal MM, Samarasena JB, Hashemzadeh M, Vega KJ. Declining hospitalization rate of esophageal variceal bleeding in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:689-695; quiz 605. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Grace ND. Diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to portal hypertension. American College of Gastroenterology Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1081-1091. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kamath PS, Kim WR; Advanced Liver Disease Study Group. The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD). Hepatology. 2007;45:797-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1075] [Cited by in RCA: 1226] [Article Influence: 68.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W; Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1229] [Cited by in RCA: 1209] [Article Influence: 67.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zaman A, Hapke RJ, Flora K, Rosen HR, Benner KG. Changing compliance to the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for the management of variceal hemorrhage: a regional survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:645-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Colapinto RF, Stronell RD, Birch SJ, Langer B, Blendis LM, Greig PD, Gilas T. Creation of an intrahepatic portosystemic shunt with a Grüntzig balloon catheter. Can Med Assoc J. 1982;126:267-268. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Bureau C, Garcia-Pagan JC, Otal P, Pomier-Layrargues G, Chabbert V, Cortez C, Perreault P, Péron JM, Abraldes JG, Bouchard L, Bilbao JI, Bosch J, Rousseau H, Vinel JP. Improved clinical outcome using polytetrafluoroethylene-coated stents for TIPS: results of a randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:469-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bureau C, Pagan JC, Layrargues GP, Metivier S, Bellot P, Perreault P, Otal P, Abraldes JG, Peron JM, Rousseau H, Bosch J, Vinel JP. Patency of stents covered with polytetrafluoroethylene in patients treated by transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: long-term results of a randomized multicentre study. Liver Int. 2007;27:742-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Angermayr B, Cejna M, Koenig F, Karnel F, Hackl F, Gangl A, Peck-Radosavljevic M; Vienna TIPS Study Group. Survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: ePTFE-covered stentgrafts versus bare stents. Hepatology. 2003;38:1043-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Monescillo A, Martínez-Lagares F, Ruiz-del-Arbol L, Sierra A, Guevara C, Jiménez E, Marrero JM, Buceta E, Sánchez J, Castellot A. Influence of portal hypertension and its early decompression by TIPS placement on the outcome of variceal bleeding. Hepatology. 2004;40:793-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 353] [Cited by in RCA: 328] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | García-Pagán JC, Caca K, Bureau C, Laleman W, Appenrodt B, Luca A, Abraldes JG, Nevens F, Vinel JP, Mössner J, Bosch J; Early TIPS (Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt) Cooperative Study Group. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2370-2379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 826] [Cited by in RCA: 842] [Article Influence: 56.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Luca A, García-Pagán JC, Bosch J, Feu F, Caballería J, Groszmann RJ, Rodés J. Effects of ethanol consumption on hepatic hemodynamics in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1284-1289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bryson CL, Au DH, Sun H, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Alcohol screening scores and medication nonadherence. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:795-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Jamal MM, Samarasena JB, Hashemzadeh M. Decreasing in-hospital mortality for oesophageal variceal hemorrhage in the USA. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:947-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bernard B, Grangé JD, Khac EN, Amiot X, Opolon P, Poynard T. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 1999;29:1655-1661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 594] [Cited by in RCA: 461] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | O’Brien JM, Lu B, Ali NA, Martin GS, Aberegg SK, Marsh CB, Lemeshow S, Douglas IS. Alcohol dependence is independently associated with sepsis, septic shock, and hospital mortality among adult intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:345-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Blanco J, Muriel-Bombín A, Sagredo V, Taboada F, Gandía F, Tamayo L, Collado J, García-Labattut A, Carriedo D, Valledor M. Incidence, organ dysfunction and mortality in severe sepsis: a Spanish multicentre study. Crit Care. 2008;12:R158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 358] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | United States Census Bureau. Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010. 2010 Demographic Profile Data, 2010. Available from: http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/pdf/census/census2010/t_sf1_dp_nyc.pdf. |