Published online Aug 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i31.10984

Revised: February 20, 2014

Accepted: May 28, 2014

Published online: August 21, 2014

Processing time: 218 Days and 23.5 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the safety and efficacy of pegylated interferon alfa-2a and ribavirin therapy in elderly patients with chronic hepatitis C infection.

METHODS: Patients characteristics, treatment results and safety profiles of 4859 patients with hepatitis c virus (HCV) infection receiving treatment with pegylated interferon alfa-2a and ribavirin were retrieved from a large ongoing German multicentre non-interventional study. Recommended treatment duration was 24 wk for GT 2 and GT 3 infection and 48 wk for GT 1 and GT 4 infection. Patients were stratified according to age (< 60 years vs≥ 60 years). Because of limited numbers of liver biopsies for further assessment of liver fibrosis APRI (aspartate aminotransferase - platelet ratio index) was performed using pre-treatment laboratory data.

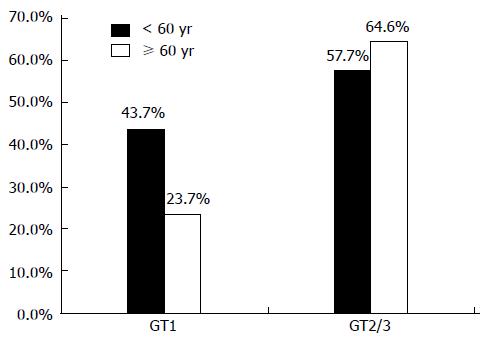

RESULTS: Out of 4859 treated HCV patients 301 (6.2%) were ≥ 60 years. There were more women (55.8% vs 34.2%, P < 0.001) and predominantly GT 1 (81.4% vs 57.3%, P < 0.001) infected patients in the group of patients aged ≥ 60 years and they presented more frequently with metabolic (17.6% vs 4.5%, P < 0.001) and cardiovascular comorbidities (32.6% vs 6.7%, P < 0.001) and significant fibrosis and cirrhosis (F3/4 31.1% vs 14.0%, P = 0.0003). Frequency of dose reduction and treatment discontinuation were significantly higher in elderly patients (30.9% vs 13.7%, P < 0.001 and 47.8% vs 30.8%, P < 0.001). Main reason for treatment discontinuation was “virological non-response” (26.6% vs 13.6%). Sustained virological response (SVR) rates showed an age related difference in patients with genotype 1 (23.7% vs 43.7%, P < 0.001) but not in genotype 2/3 infections (57.7% vs 64.6%, P = 0.341). By multivariate analysis, age and stage of liver disease were independent factors of SVR.

CONCLUSION: Elderly HCV patients differ in clinical characteristics and treatment outcome from younger patients and demand special attention from their practitioner.

Core tip: There are concerns to initiate treatment in elderly patients because of perceived lower sustained virological response (SVR) rates and serious adverse events. We aimed to evaluate safety and efficacy of pegylated interferon alfa-2a and ribavirin therapy in elderly patients. Patients were stratified according to age (< 60 years vs≥ 60 years). SVR rates showed an age related difference in patients with genotype 1 (23.7% vs 43.7%, P < 0.001) but not in genotype 2/3 infections (57.7% vs 64.6%, P = 0.341). Elderly hepatitis C virus patients differ in clinical characteristics and treatment outcome from younger patients and demand special attention from their practitioner.

- Citation: Roeder C, Jordan S, Schulze zur Wiesch J, Pfeiffer-Vornkahl H, Hueppe D, Mauss S, Zehnter E, Stoll S, Alshuth U, Lohse AW, Lueth S. Age-related differences in response to peginterferon alfa-2a/ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(31): 10984-10993

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i31/10984.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i31.10984

According to the estimation of the World Health Organization about 2% to 3% of the world’s population is chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), which amounts to approximately 130-170 million people[1,2]. In Germany, community-based studies showed an overall prevalence of HCV-antibodies of about 0.5% in the adult population[3], representing 400000 to 500000 chronic infected people.

In western countries, contaminated blood products were the greatest risk factor for acquiring HCV infection before 1990, being replaced by intravenous drug abuse (IVDA) after 1990[4]. Nowadays IVDA remains a main risk factor together with sexual behavior (Men Who have Sex with Men) as well as tattooing. The number of iatrogenic infections is decreasing but infections still occur occasionally[5-9].

Since the rate of new infections has decreased over the last couple of years and the prevalence has peaked in western countries about a decade ago, the average age of the HCV patients has increased over the years[10].

The safety and efficacy of pegylated interferon (pegIFN) - based treatment regimens have been studied extensively[11,12] and have shown to reduce the risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and improve the survival of patients who achieve a sustained virological response (SVR)[13,14]. However, treatment is still relatively costly, burdensome for the patient and serious adverse events can occur[15]. The recent introduction of protease inhibitors for combination triple therapy has shortened average treatment duration and improved the treatment outcome of patients with HCV genotype 1 infection considerably[16-18].

An increasing risk of liver cirrhosis and HCC development with advanced age has been repeatedly shown[10,19-22]. Hence, elderly patients are in special need of an effective antiviral treatment. However, co-morbidities like diabetes mellitus, co-medication and the risk of advanced liver fibrosis commonly found in older patients are known unfavourable factors for treatment outcome[23], others like coronary heart disease are important relative contraindications for treatment[15]. In addition, adverse events and poor tolerability increase with age according to some studies[24]. As most clinical trials exclude patients above 65 years, safety and efficacy data for the treatment of older patients is limited. Thus, older patients as well as their attending physicians are often hesitant towards initiating a treatment course[25,26].

With the advent of novel treatment options providers have to weigh whether to initiate standard dual treatment in patients with genotype 1 or alternatively start with the novel triple therapy, which is associated with higher chance of attaining an SVR but also higher risk of serious adverse events. Alternatively, they might decide to defer treatment until after the introduction of interferon-free combination treatment options which are expected in the next couple of years[27,28]. However, due to the high cost of the novel direct antiviral agents pegIFN and ribavirin (RBV) will remain the standard of care in many countries.

German and European HCV guidelines give little or no guidance about until which age elderly patients should be treated nor even mention the issue of the ageing of HCV patients[29,30].

Only few studies with limited patient numbers and variable protocols studied the safety and efficacy of pegIFN and ribavirin in older patients with CHC[31-38]. Study results regarding SVR rates in elderly patients are inconsistent. Lower SVR rates and higher rates of adverse events and treatment discontinuation have been observed in most western studies[32,35-37,39]. These studies were mostly limited due to small patient numbers. In contrast, recently published Asian studies showed higher SVR rates in general[32,34,35] and a negligible influence of age on safety and efficacy[31,34]. The discrepancy of study results might be explained by distinct host genetic factors (such as a favourable IL28b polymorphism)[38].

The aim of the present study was to examine the safety and efficacy of pegIFN and ribavirin combination therapy in elderly patients in a large “real life” German cohort study.

This analysis is part of an ongoing German multicenter non-interventional study (ML21645) of patients with CHC receiving pegylated interferon alfa-2a and RBV, involving 379 physicians/institutions throughout Germany (328 in private practice and 51 in hospital settings). The study is ongoing since March 2003 and is approved by health authorities and ethical committees. Data of 4859 patients with completed documentation of treatment course at July 2011 were analysed. Recommended treatment duration was 24 wk for GT 2 and GT 3 infection and 48 wk for GT 1 and GT 4 infection. The treatment period was followed by an observational period of 24 wk. The recommended dosage of pegylated interferon alfa-2a was 180 μg once weekly in combination with RBV according to the SPCs of manufacturers. Inclusion criteria were age of at least 18 years, quantifiable HCV-RNA, compensated liver disease and written consent. SVR was defined as non-detectable HCV-RNA 24 wk after completion of the treatment period. Virological failure was defined as < 2 log decline of HCV RNA from baseline at week 12.

Data were obtained on structured questionnaires. Screening data included demographic data, history of HCV infection and concomitant diseases. During the treatment course information about virological response and drug safety was collected using online data entry. The study represents an unselected cohort in a real life setting including a significant fraction of all patients treated for hepatitis C mono-infection in Germany.

Because of limited numbers of liver biopsies for further assessment of liver fibrosis APRI (aspartate aminotransferase - platelet ratio index) was performed using pre-treatment laboratory data. APRI is a non-invasive indirect biochemical marker of hepatic fibrosis using routine laboratory parameters to distinguish fibrosis stages. APRI was calculated according to the formula proposed by Wai et al[40] in 2003: [(AST of the sample/reference AST) × 100]/platelets. Results were categorized as followed: ≤ 0.5 (no fibrosis); > 0.5-≤ 1.5 (mild fibrosis); > 1.5-≤ 2 (significant fibrosis); > 2 (cirrhosis).

The statistical analysis was descriptive to reflect the clinical routine as intended by the clinicians. Summary statistics (mean, median, standard deviation, 25th percentile, 75th percentile, minimum, maximum, number of values) or frequencies and proportions were assessed dependant on the scale level of the data.

Differences in baseline clinical characteristics, safety and efficacy data among the patient groups were compared statistically, using t test, χ2 tests (Pearson and Fisher’s exact test) and multivariate logistic regression analysis including OR and 95%CI.

All statistical analyses were based on 2-sided hypothesis tests. Analyses were calculated using SPSS for Windows Release 12.0.1, Testimate Version 6.4.27 and Matched Version 1.1.

Our analysis included 4859 patients infected with different HCV genotypes who were treated with a combination of pegylated interferon alfa-2a and a fix dosed or weight adjusted RBV. 4558 patients (93.8%) were < 60 years and only 301 patients (6.2%) were aged 60 years and older. Baseline characteristics, as shown in Table 1, differed in gender distribution, there were more women (55.8% vs 34.2%, P < 0.001) and predominantly GT 1 (81.4% vs 57.3%, P < 0.001) infected patients in the group of patients aged ≥ 60 years. There were no differences in racial distribution in both age groups with the vast majority of patients being caucasian. Providers assessed the fibrosis status more thoroughly in elderly patients and liver biopsies were performed more often in patients ≥ 60 years (29.9% vs 16.4%, P < 0.001). Liver biopsies displayed more advanced liver fibrosis in the older group (F3/4 31.1% vs 14.0%, P = 0.0003). For further assessment of fibrosis APRI was analysed for all patients. Approximately 30% of elderly patients showed significant fibrosis or cirrhosis (APRI ≥ 1.5) compared to 14.2% in the younger age group. Only 19.8% of elderly patients vs 43.3% of younger patients reached a score < 0.5 (Table 1).

| Patients | < 60 yr | ≥ 60 yr | P value |

| Mean age | 4558 (94.0) | 301 (6.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Gender | < 0.0001 | ||

| Male | 3001 (65.8) | 133 (44.2) | - |

| Female | 1557 (34.2) | 168 (55.8) | - |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 4373 (95.9) | 289 (96.0) | |

| African | 78 (1.7) | 6 (2.0) | |

| Asian | 88 (1.9) | 5 (1.7) | |

| Hispanic | 16 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Unknown/other | 3 (0.1) | 0 | |

| Genotype | < 0.0001 | ||

| 1 | 2614 (57.3) | 245 (81.4) | - |

| 2 | 258 (5.7) | 27 (9.0) | - |

| 3 | 1480 (32.5) | 21 (7.0) | - |

| Others (4, 5, 6) | 206 (4.5) | 8 (2.6) | |

| Initial viral load | |||

| > 1 Mio copies/mL | 2659 (58.9) | 193 (64.5) | 0.0830 |

| Thrombocytes (/μL) | 221.259 (635-595000; SD 71.884) | 186.433 (21000-557500; SD 70546) | |

| Within normal range | 3736 (85.1) | 207 (72.9) | |

| (140000-360000 c/μL) | |||

| Below normal range | 503 (11.5) | 72 (25.4) | |

| (< 140000 c/μL) | |||

| Above normal range | 150 (3.4) | 5 (1.8) | |

| (> 360000 c/μL) | |||

| GPT/ALT (U/L) | 107 (4-1409; SD 103) | 115 (20-591; SD 89) | |

| Within normal range | 882 (20.0) | 27 (9.5) | |

| (Male ≥ 50 U/L; | |||

| Female < 35 U/L) | |||

| Above normal range | 3521 (80.0) | 258 (90.5) | |

| (Male ≥ 50 U/L; | |||

| Female ≥ 35 U/L) | |||

| GOT/AST (U/L) | 74 (10-2880; SD 87) | 92 (18-526; SD 71) | |

| Within normal range | 1530 (36.5) | 43 (16.3) | |

| (Male < 50 U/L; | |||

| Female < 35 U/L) | |||

| Above normal range | 2658 (63.5) | 221 (83.7) | |

| (Male ≥ 50 U/L; | |||

| Female ≥ 35 U/L) | |||

| GGT (U/L) | 96 (4-1871; SD 129) | 111 (9-1240; SD 137) | |

| Within normal range | 2186 (50.2) | 98 (35.4) | |

| (Male < 66 U/L; | |||

| Female < 39 U/L) | |||

| Above normal range | 2165 (49.8) | 179 (64.6) | |

| (Male ≥ 66 U/L; | |||

| Female ≥ 39 U/L) | |||

| INR | |||

| < 1.7 | 2758 (98.1) | 182 (95.3) | |

| 1.7-2.3 | 31 (1.1) | 4 (2.1) | |

| > 2.3 | 22 (0.8) | 5 (2.6) | |

| Body mass index | 25.2 | 26.5 | 0.000 |

| (mean value) | |||

| Treatment naive | 4038 (88.6) | 253 (84.1) | 0.0176 |

| Estimated duration of infection (yr) | 11.6 | 19.9 | 0.000 |

| Histology available in Degree of Fibrosis | 746 (16.4) | 90 (29.9) | < 0.0001 |

| P value adjusted | 0.0003 | ||

| (0-4 without unknown) | |||

| F0/1/2 | 533 (71.4) | 48 (53.3) | |

| F3/4 | 104 (14.0) | 28 (31.1) | |

| Unknown | 109 (14.6) | 14 (15.6) | |

| APRI score | < 0.0001 | ||

| < 1.5 | 3526 (85.7) | 181 (70.2) | |

| ≥ 1.5 | 587 (14.3) | 77 (29.8) | |

| Duration of therapy | 32.5 | 33.0 | 0.6250 |

| (mean value) (wk) | |||

| Co-morbidities | 0.6198 | ||

| (with/none) | |||

| None | 1792 (39.3) | 114 (37.9) | - |

| With | 2766 (60.7) | 187 (62.1) | - |

| Cardiac | 305 (6.7) | 98 (32.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Metabolic | 204 (4.5) | 53 (17.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Drugs and alcoho | 1469 (32.2) | 10 (3.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Psychogenic | 768 (16.8) | 26 (8.6) | < 0.0002 |

| Skin | 116 (2.5) | 8 (2.7) | 0.8500 |

As marker for liver synthesis values for International Normalized Ratio were categorized according to CHILD PUGH score. Only very few patients in both groups showed compromised coagulation. No significant difference was found in number of patients with pronounced coagulation disorder (Table 1).

As indirect markers of liver inflammation screening values of aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase were analysed. AST was elevated in 83.7% of elderly patients and 63.5% of patients < 60 years with mean values of 92 U/L respectively 74 U/L. ALT was elevated in 90.5% of elderly patients and 80.0% of patients < 60 years, mean values 115 U/L respectively 107 U/L. Thrombocyte counts below normal range were seen in 25.4% of elderly patients compared to 11.5% in patients < 60 years (Table 1).

Comorbidities did not differ in number but in quality between both age groups. While metabolic (17.6%) and cardiovascular diseases (32.6%) dominated in patients ≥ 60 years, whereas drug and alcohol addiction (32.2%) as well as general psychological disorders (16.9%) were more frequent in patients < 60 years. The majority of older patients could not define the mode of HCV transmission. Main route of transmission in the group ≥ 60 years was blood transfusion (21.9%) followed by surgery (7.6%). In younger patients intravenous drug abuse was the most frequent reported transmission route (46.2%). Mean duration of infection was 19.9 years in older patients vs 11.6 years in younger patients (P < 0.001). The majority of patients in both age groups (older patients vs younger patients) were previously untreated. The percentage of untreated patients was slightly lower in the older age group (84.1% vs 88.6%, P = 0.02). HCV viral load prior to treatment stratified in low and high viral load (as defined by a cut of 400000 IE/mL) was not significantly different in either age groups (Table 1).

Generally HCV dual combination treatment with interferon/ribavirin was relatively safe regardless of the age group. However, treatment had to be stopped more often in patients ≥ 60 years (47.8% vs 30.8%, P < 0.001). Main causes for treatment discontinuation in the older patients compared to younger patients were: virological failure [26.6% vs 13.6%, P < 0.001; OR = 2.291 (95%CI: 1.750-2.999)], adverse events [11.3% vs 3.1%, P < 0.001; OR = 3.960 (95%CI: 2.670-5.873)], patient request [7.3% vs 4.6%, P = 0.035; OR = 1.633 (95%CI: 1.035-2.575)], aggravating co-morbidities [2.3% vs 0.9%, P = 0.020; OR = 2.623 (95%CI: 1.167-5.898)], and death during therapy [1.0% vs 0.3%, P = 0.039; OR = 3.814 (95%CI: 1.070-13.588)], as depicted in Table 2.

| All genotypes | P value | OR (95%CI) | Genotype 1 | P value | OR (95%CI) | |||

| < 60 yr | ≥ 60 yr | < 60 yr | ≥ 60 yr | |||||

| Treatment discontinuation | 1402 (30.8) | 144 (47.8) | 0.000 | 2.065 (1.633-2.611) | 985 (37.7) | 134 (54.7) | 0.000 | 1.996 (1.534-2.599) |

| Non-response | 622 (13.6) | 80 (26.6) | 0.000 | 2.291 (1.750-2.999) | 535 (20.5) | 78 (31.8) | 0.000 | 1.815 (1.365-2.414) |

| Lost to follow up | 323 (7.1) | 6 (2.0) | 0.002 | 0.267 (0.118-0.603) | 176 (6.7) | 4 (1.6) | 0.004 | 0.230 (0.085-0.625) |

| Adverse events | 142 (3.1) | 34 (11.3) | 0.000 | 3.960 (2.670-5.873) | 89 (3.4) | 30 (12.2) | 0.000 | 3.959 (2.558-6.126) |

| Of them due to intolerance RBV | 49 (1.1) | 19 (6.3) | 0.000 | 6.200 (3.602-10.673) | 35 (1.3) | 16 (6.5) | 0.000 | 5.148 (2.807-9.444) |

| Of them due to intolerance IFN | 91 (2.0) | 23 (7.6) | 0.000 | 4.061 (2.530-6.519) | 62 (2.4) | 21 (8.6) | 0.000 | 3.859 (2.309-6.448) |

| Patient request | 210 (4.6) | 22 (7.3) | 0.035 | 1.633 (1.035-2.575) | 127 (4.9) | 21 (8.6) | 0.013 | 1.836 (1.134-2.971) |

| Compliance | 160 (3.5) | 3 (1.0) | 0.028 | 0.277 (0.088-0.872) | 87 (3.3) | 2 (0.8) | 0.046 | 0.239 (0.058-0.977) |

| Co-morbidities | 41 (0.9) | 7 (2.3) | 0.020 | 2.623 (1.167-5.898) | 30 (1.1) | 6 (2.4) | 0.081 | |

| Death | 12 (0.3) | 3 (1.0) | 0.039 | 3.814 (1.070-13.588) | 10 (0.4) | 3 (1.0) | 0.061 | |

| Others | 74 (1.6) | 2 (0.7) | 0.194 | 50 (1.9) | 2 (0.8) | 0.219 | ||

Lack of compliance and lost-to-follow up were less common in older patients than younger patients (1.0% and 2.0% vs 3.5% and 7.1%).

The rates of drug modification are presented in Table 3. Patients ≥ 60 years had significant higher rates of dose modifications [30.9% vs 13.7%, P < 0.001; OR = 2.814 (95%CI: 2.172-3.644)] with reduction of both treatment components in 6.0% and reduction of just RBV and pegylated interferon alfa-2a, respectively, in 18.3% and 6.6% compared to 2.5% [P < 0.001; OR = 1.349 (95%CI: 1.138-1.600)], 6.3% [P < 0.001; OR = 1.827 (95%CI: 1.560-2.140)] and 4.9% (P = 0.183) in patients < 60 years.

| All genotypes | P value | OR (95%CI) | Genotype 1 | P value | OR (95%CI) | |||

| < 60 yr(n = 4558) | ≥ 60 yr(n = 301) | < 60 yr(n = 2614) | ≥ 60 yr(n = 245) | |||||

| No dose reduction | 3933 (86.3) | 208 (69.1) | 0.000 | 2.814 (2.172-3.644) | 2204 (84.3) | 166 (67.8) | 0.000 | 2.558 (1.918-3.412) |

| Reduction of RBV | 286 (6.3) | 55 (18.3) | 0.000 | 1.827 (1.560-2.140) | 190 (7.3) | 47 (19.2) | 0.000 | 1.74 (1.460-2.074) |

| Reduction of | 224 (4.9) | 20 (6.6) | 0.183 | 129 (4.9) | 17 (6.9) | 0.173 | ||

| pegINF α2a | ||||||||

| Reduction of RBV and pegINF α2a | 115 (2.5) | 18 (6.0) | 0.001 | 1.349 (1.138-1.600) | 91 (3.5) | 15 (6.1) | 0.039 | 1.218 (1.010-1.470) |

SVR was achieved in 94 of 301 patients ≥ 60 years and in 2230 of 4558 patients < 60 years (31.2% vs 48.9%, P < 0.001). Substratification for the different genotypes revealed that for GT-1 58 of 245 in elderly patients and 1142 of 2614 in younger patients achieved sustained virological response (23.7% vs 43.7%, P < 0.001). For GT 2 or GT 3 infections SVR rates were similar in both age groups (64.6% ≥ 60 years vs 57.7% < 60 years, P = 0.341) (Figure 1).

Treatment naïve patients showed the same significant difference in treatment response in genotype 1 patients (26.1% ≥ 60 years vs 45.9% < 60 years, P < 0.001). SVR rates for GT2/3 patients were again similar in both age groups (67.4% ≥ 60 years vs 58.8% < 60 years, P = 0.341). Treatment experienced patients achieved significant lower SVR rates for all genotypes and age groups as shown in Table 4.

| Patients | < 60 yr | ≥ 60 yr | P value |

| Mean age | 4558 (94.0) | 301 (6.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Gender | < 0.0001 | ||

| Male | 3001 (65.8) | 133 (44.2) | - |

| Female | 1557 (34.2) | 168 (55.8) | - |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 4373 (95.9) | 289 (96.0) | |

| African | 78 (1.7) | 6 (2.0) | |

| Asian | 88 (1.9) | 5 (1.7) | |

| Hispanic | 16 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Unknown/other | 3 (0.1) | 0 | |

| Genotype | < 0.0001 | ||

| 1 | 2614 (57.3) | 245 (81.4) | - |

| 2 | 258 (5.7) | 27 (9.0) | - |

| 3 | 1480 (32.5) | 21 (7.0) | - |

| Others (4, 5, 6) | 206 (4.5) | 8 (2.6) | |

| Initial viral load | |||

| > 1 Mio copies/mL | 2659 (58.9) | 193 (64.5) | 0.0830 |

| Thrombocytes (/μL) | 221.259 (635-595000; SD 71.884) | 186.433 (21000-557500; SD 70546) | |

| Within normal range | 3736 (85.1) | 207 (72.9) | |

| (140000-360000 c/μL) | |||

| Below normal range | 503 (11.5) | 72 (25.4) | |

| (< 140000 c/μL) | |||

| Above normal range | 150 (3.4) | 5 (1.8) | |

| (> 360000 c/μL) | |||

| GPT/ALT (U/L) | 107 (4-1409; SD 103) | 115 (20-591; SD 89) | |

| Within normal range | 882 (20.0) | 27 (9.5) | |

| (Female < 35 U/L) | |||

| Above normal range | 3521 (80.0) | 258 (90.5) | |

| (Male ≥ 50 U/L; | |||

| Female ≥ 35 U/L) | |||

| GOT/AST (U/L) | 74 (10-2880; SD 87) | 92 (18-526; SD 71) | |

| Within normal range | 1530 (36.5) | 43 (16.3) | |

| (Male < 50 U/L; | |||

| Female < 35 U/L) | |||

| Above normal range | 2658 (63.5) | 221 (83.7) | |

| (Male ≥ 50 U/L; | |||

| Female ≥ 35 U/L) | |||

| GGT (U/L) | 96 (4-1871; SD 129) | 111 (9-1240; SD 137) | |

| Within normal range | 2186 (50.2) | 98 (35.4) | |

| (Male < 66 U/L; | |||

| Female < 39 U/L) | |||

| Above normal range | 2165 (49.8) | 179 (64.6) | |

| (Male ≥ 66 U/L; | |||

| Female ≥ 39 U/L) | |||

| INR | |||

| < 1.7 | 2758 (98.1) | 182 (95.3) | |

| 1.7-2.3 | 31 (1.1) | 4 (2.1) | |

| > 2.3 | 22 (0.8) | 5 (2.6) | |

| Body mass index | 25.2 | 26.5 | 0.000 |

| (mean value) | |||

| Treatment naive | 4038 (88.6) | 253 (84.1) | 0.0176 |

| Estimated duration of infection (yr) | 11.6 | 19.9 | 0.000 |

| Histology available in Degree of Fibrosis | 746 (16.4) | 90 (29.9) | < 0.0001 |

| P value adjusted | 0.0003 | ||

| (0-4 without unknown) | |||

| F0/1/2 | 533 (71.4) | 48 (53.3) | |

| F3/4 | 104 (14.0) | 28 (31.1) | |

| Unknown | 109 (14.6) | 14 (15.6) | |

| APRI score | < 0.0001 | ||

| < 1.5 | 3526 (85.7) | 181 (70.2) | |

| ≥ 1.5 | 587 (14.3) | 77 (29.8) | |

| Duration of therapy | 32.5 | 33.0 | 0.6250 |

| (mean value) (wk) | |||

| Co-morbidities | 0.6198 | ||

| (with/none) | |||

| None | 1792 (39.3) | 114 (37.9) | - |

| With | 2766 (60.7) | 187 (62.1) | - |

| Cardiac | 305 (6.7) | 98 (32.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Metabolic | 204 (4.5) | 53 (17.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Drugs and alcoho | 1469 (32.2) | 10 (3.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Psychogenic | 768 (16.8) | 26 (8.6) | < 0.0002 |

| Skin | 116 (2.5) | 8 (2.7) | 0.8500 |

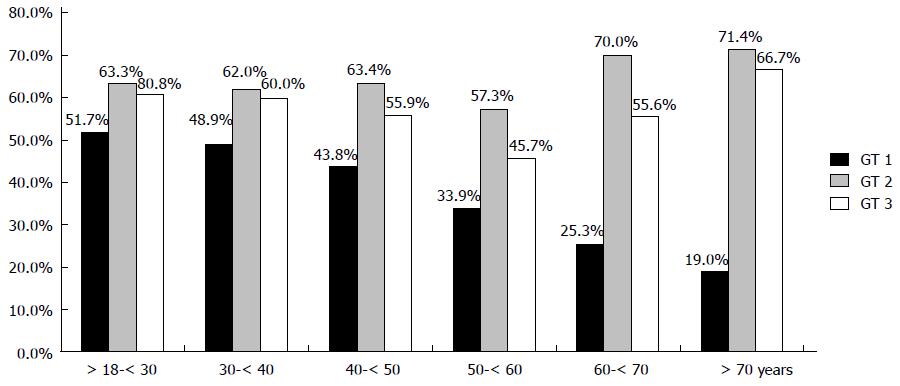

In addition, SVR rates were stratified according to decades of age (Figure 2). For GT 1-infection a continuous decline in SVR rate with increasing decades of age was determined. In contrast, no significant difference in SVR rates for older patients with GT 2 and GT 3 was seen (Figure 2).

SVR rates were further stratified for APRI score < 1.5 vs≥ 1.5 consistent with no or mild fibrosis vs severe fibrosis or cirrhosis. In elderly patients no significant difference in treatment response according to fibrosis stage was seen. In contrast, patients < 60 years showed significant lower SVR rates in patients with an APRI score ≥ 1.5. Data are consistent when stratified for GT 1 and GT 2/3 (Table 5).

| APRI score | SVR n (%) | P | |

| GT 1 | χ2test | ||

| < 60 yr | < 1.5 | 936 (45.7) | 0.000 |

| ≥ 1.5 | 99 (31.2) | ||

| ≥ 60 yr | < 1.5 | 40 (26.5) | 0.476 |

| ≥1 .5 | 12 (20.7) | ||

| GT 2/3 | |||

| < 60 yr | < 1.5 | 799 (60.8) | 0.000 |

| ≥ 1.5 | 106 (43.6) | ||

| ≥ 60 yr | < 1.5 | 18 (66.7) | 0.526 |

| ≥ 1.5 | 9 (52.9) |

Age and stage of liver disease in contrast to treatment discontinuation due to ribavirin and PEG-IFN adverse events were independent factors of SVR rates as shown in a multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 6).

| Sig. | Exp (B) | 95%CI for EXP(B) | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Fibrosis stage F4 vs Fibrosis stage F0, F1, F2, F3 | 0.004 | 0.717 | 0.573 | 0.897 |

| Age 60 yr vs < 60 yr | 0.003 | 0.427 | 0.243 | 0.750 |

| Treatment discontinuation due to ribavirin adverse events | 0.142 | |||

| Treatment discontinuation due to Peg-IFN adverse events | 0.998 | |||

Despite the enormous data set and experience we have generated for standard combination interferon treatment for chronic HCV infection over the last decade, the growing population of elderly patients is a relatively understudied population. Many of the major registration trials excluded patients aged > 65 years. Also, clinical guidelines give no detailed advice for treatment of the elderly patient group[29,30], which is generally regarded as difficult to treat population due to higher rates of fibrosis and co-morbidities.

In this substudy of this ongoing German multicenter non-interventional study we evaluate the safety and efficacy of a combination therapy with pegylated interferon alfa-2a and RBV in HCV-positive patients ≥ 60 years in comparison to patients < 60 years.

Notably, only 6.2% (301/4859) of all treated patients were ≥ 60 years suggestive of a relative under-treatment of elderly HCV-infected patients. As our study only included patients in whom treatment was initiated no data of treatment uptake rates for the different age groups are available. For previous analyses of the ongoing study data of all patients screened for possible HCV therapy was obtained. A first epidemiological study showed a high percentage of elderly patients in the group of all HCV patients with 26.3% (2716/10326) of the patients being ≥ 60 years old[41]. A second study showed a significant lower rate of treatment uptake in patients > 56 years compared to patients ≤ 56 years (28.2% vs 49%) - in patients aged between 65 and 70 years treatment rate was 26.3%[42]. An Italian cross-sectional study and the Veterans Affairs Medical Centres Study both showed that advanced age is often the main reason to exclude elderly patients from treatment[25,26]. Additional studies are needed to evaluate the general treatment assessment of elderly patients and further characterize the group of patients who are a priori excluded from treatment.

Consistent with data from other Western countries[36,37,43] patient’s characteristics differed significantly in gender, genotype, co-morbidities and transmission risk. Patients ≥ 60 years were rather female, more likely infected with GT 1, suffering from metabolic or cardiovascular diseases and being infected iatrogenic. Not surprisingly, older patients showed more advanced liver disease. As histology was assessed only in about one third of the patients APRI score was performed for all patients. Data were consistent with the results of histology with about 30% of patients in the elderly group reaching a score of > 1.5 consistent with significant fibrosis or cirrhosis. On the other hand, approximately 20% of the older patient cohort did show little or no signs of fibrosis. The benefit of treating these patients is not so clear, especially in the absence of symptoms in some of these patients. In a Japanese cohort study only patients with a reduced platelet count as marker of advanced fibrosis showed significantly differences in hepatocarcinogenesis and survival compared to an untreated reference group[44].

Elderly patients had a significantly higher rate of treatment discontinuation (47.8% vs 30.8%, P < 0.001). The main reason was non-response (26.6%).

In 11.3% treatment was interrupted due to adverse events, another 7.3% of the patients requested premature discontinuation. Surprisingly, despite a high rate of metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities in the elderly, treatment was stopped due to worsening of these underlying diseases only in 7/301 (2.3%) patients. 3 patients (1%) in the elderly patients group died during therapy - 2 of them due to complications of liver cirrhosis, the other patient due to deterioration of general condition. Mortality rate in the younger patients was slightly lower with 12/4558 (0.3%). Causes of death in the younger age group were infectious complications, drug overdose and suicide, cardiovascular disease, liver failure and pulmonary embolism. The slightly higher mortality rate in elderly patients might be probably due to the low number of patients as well as due to the general higher mortality in advanced age. Treatment adherence was slightly higher in older patients, compliance problems occurred in only about 1% vs 3.5% in younger patients and only 2% vs 7.1% were lost to follow-up.

As reported before[31-33], we also noted more dose modifications during HCV therapy in elderly compared to younger patients. It is not entirely clear whether these modifications were always justified or whether the providers acted with extra care for fear of adverse events, e.g. cardiac ischemia due to anaemia. In nearly one third of the patients the initial dose of one or both drugs had to be reduced during the treatment course. In 24.3% of older patients RBV dose was reduced.

Treatment response in patients with GT 1 was substantially lower in patients ≥ 60 years (23.7% vs 43.7%, P < 0.001). Furthermore, we found a continuous decline in sustained virological response rates over age for GT 1 infections when classifying them into groups by decades (Figure 2). Consistent with recently published data[31,34,36], no significant difference in the SVR rates was found for GT 2 and GT 3 infections. As expected, treatment response was substantially lower for retreated patients. 5 out 42 (11.9%) elderly patients with GT 1 infection achieved SVR. In GT 2/3 patients only 5 patients were pre-treated, two of them were retreated successfully. Stratified for stage of fibrosis advanced fibrosis (APRI score > 1.5) was clearly associated with a lower treatment response in patients < 60 years both for GT 1 and GT2/3 infections. No such correlation was seen in the group of elderly patients. Still lower SVR rates were found for APRI score 1.5 but the results were not statistically significant which might mainly explained due to the small patient numbers. Age and stage of liver disease (fibrosis stage 4 vs other fibrosis stage) could be shown as independent factors of treatment response in multivariate regression analysis.

Recently published data of treatment outcome in elderly patients with pegylated IFN based regimens showed consistently higher SVR rates ranging from 40.7%[34] up to 67.1%[31] for GT 1 infections and 76.7%[31] and 86.4%[34] for GT 2 or GT 3. Both studies were conducted in Asian patients who generally show higher response rates compared to Caucasians and Afro-Americans mainly due to host genetic variations e.g., the recently described IL28B polymorphisms[38].

The relatively low SVR rates in older patients are mainly caused by higher rates of virological non-response to dual therapy, which might be due to the difference in quality not in quantity of comorbidities as well as advanced liver fibrosis. But still, it could be shown that age is an independent factor for SVR. The reason remains unknown. Altered IFN-immunomodulation and pharmacokinetics in elderly patients might influence the response to therapy. Their affect has to be evaluated further. These factors might even become more apparent with longer duration of therapy and may explain that age-dependent differences in SVR rates seen in patients with genotype 1 infections in contrast to similar SVR rates in all age groups for genotype 2 and 3 infections in whom duration of therapy is markedly lower.

The recently approved new direct antiviral agents such as protease inhibitors and polymerase inhibitors might provide more effective treatment options. Triple therapy regimens with the protease inhibitors telaprevir or boceprevir have to be considered for many elderly GT 1 patients despite the possibility of further side-effects. Both drugs showed only slightly lower SVR rates in patients > 40 years compared to patients < 40 years in phase III-trials[16,17]. But the clinical studies did not include sufficient numbers of patients ≥ 60 years to prove the superior efficacy for this age group.

Furthermore, protease inhibitors may hold new obstacles such as drug drug interactions with concomitant medication. Adverse events like anaemia and rash will require an even more intense monitoring of the patient during treatment course[45,46]. Studies to assess the safety and efficacy of triple therapy in older patients are urgently needed. The low SVR rates of dual therapy and possible complications of protease inhibitor based triple therapy might indeed be an argument for postponement of treatment in some patients until the interferon free regimens will become widely available[27,28]. The nucleotide NS5B polymerase inhibitor Sofosbuvir has been approved for HCV therapy by FDA in the end of 2013 offering the first IFN-free treatment alternative for patients with genotype 2 or 3 infections and those with contraindications against interferon[47-49].

In contrast, the SVR rates remain high for GT 2 and GT 3 patients even with increasing age but small patient numbers have to be taken into account. Still, our findings are consistent with previously published data[31,34,36]. In respect of SVR rates of up to 65% regardless of age, short treatment duration and relative low cost of dual treatment, there is less of a rationale to postpone treatment until the introduction of intensified treatment regimens or interferon-free combination treatment.

We conclude that the elderly HCV patient is still understudied and not well understood. National and European guidelines should take into account the general ageing of HCV patients in Europe. Despite higher rates of treatment discontinuation and lower SVR rates in GT 1 infection, HCV-therapy in elderly patients is well feasible in “real life” experience. Therefore elderly patients should not be excluded from assessment for treatment a priory. We suggest making informed decisions on individual basis and taking all of the patient’s circumstances into account, such as stage of liver disease, clinical symptoms and comorbidities as well as virological parameters, treatment history and further predictive parameters. New therapy regimens containing more potent direct antiviral agents may enhance treatment outcome in elderly patients but further studies to examine the effect of age on safety and efficacy of these agents are urgently needed. Still, pegylated interferon based dual therapy will remain the standard of care for treatment of hepatitis C in many countries to the immense cost of the novel direct antiviral agents.

The average age of hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients is increasing over time. There are concerns to initiate treatment in elderly patients because of perceived lower sustained virological response (SVR) rates and serious adverse events. As elderly patients were excluded from most clinical trials in the past, safety and efficacy data for the treatment of elderly patients is limited. Therefore, the authors aimed to evaluate safety and efficacy of pegylated interferon alfa-2a and ribavirin therapy in patients > 60 years.

The safety and efficacy of pegylated interferon - based treatment regimens in patients with hepatitis C infection have been studied extensively and have shown to reduce the risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma and improve the survival of patients who achieve a sustained virological response. However, only few studies with limited patient numbers and variable protocols studied the safety and efficacy of pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy in elderly patients. Furthermore, study results regarding SVR rates in elderly patients are inconsistent.

The study represents an unselected cohort in a real life setting including a significant fraction of all patients treated for hepatitis C mono-infection in Germany providing safety and efficacy data on pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy in 301 patients > 60 years.

The study highlights that elderly HCV patients differ in clinical characteristics and treatment outcome from younger patients and that they demand special attention from their practitioner. Still, despite higher rates of treatment discontinuation and lower SVR rates in GT 1 infection, HCV-therapy in elderly patients is well feasible in “real life” experience. Therefore elderly patients should not be excluded from assessment for treatment a priory. Informed decisions should be made on individual basis and taking all of the patient´s circumstances into account, such as stage of liver disease, clinical symptoms and comorbidities as well as virological parameters, treatment history and further predictive parameters.

The authors of this study present a report on HCV treatment efficacy and safety/tolerability in elderly patients. The subject is important and the authors performed a good study on this subject. The paper is original, very interesting and very well-written.

P- Reviewer: Borgia G, Song M S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2436-2441. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:558-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1927] [Cited by in RCA: 1931] [Article Influence: 96.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cornberg M, Razavi HA, Alberti A, Bernasconi E, Buti M, Cooper C, Dalgard O, Dillion JF, Flisiak R, Forns X. A systematic review of hepatitis C virus epidemiology in Europe, Canada and Israel. Liver Int. 2011;31 Suppl 2:30-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Alter MJ. HCV routes of transmission: what goes around comes around. Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31:340-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Guadagnino V, Stroffolini T, Caroleo B, Menniti Ippolito F, Rapicetta M, Ciccaglione AR, Chionne P, Madonna E, Costantino A, De Sarro G. Hepatitis C virus infection in an endemic area of Southern Italy 14 years later: evidence for a vanishing infection. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:403-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gentile I, Di Flumeri G, Scarica S, Frangiosa A, Foggia M, Reynaud L, Borgia G. Acute hepatitis C in patients undergoing hemodialysis: experience with high-dose interferon therapy. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2013;65:83-84. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Carney K, Dhalla S, Aytaman A, Tenner CT, Francois F. Association of tattooing and hepatitis C virus infection: a multicenter case-control study. Hepatology. 2013;57:2117-2123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | van de Laar TJ, van der Bij AK, Prins M, Bruisten SM, Brinkman K, Ruys TA, van der Meer JT, de Vries HJ, Mulder JW, van Agtmael M. Increase in HCV incidence among men who have sex with men in Amsterdam most likely caused by sexual transmission. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:230-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gentile I, De Stefano A, Di Flumeri G, Buonomo AR, Carlomagno C, Morisco F, De Placido S, Borgia G. Concomitant interferon-alpha and chemotherapy in hepatitis C and colorectal cancer: a case report. In Vivo. 2013;27:527-529. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Davis GL, Alter MJ, El-Serag H, Poynard T, Jennings LW. Aging of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected persons in the United States: a multiple cohort model of HCV prevalence and disease progression. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:513-521, 521.e1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 671] [Cited by in RCA: 666] [Article Influence: 44.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M, Albrecht JK. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4736] [Cited by in RCA: 4558] [Article Influence: 189.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Gonçales FL, Häussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4847] [Cited by in RCA: 4748] [Article Influence: 206.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Singal AK, Singh A, Jaganmohan S, Guturu P, Mummadi R, Kuo YF, Sood GK. Antiviral therapy reduces risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:192-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Arase Y, Ikeda K, Suzuki F, Suzuki Y, Saitoh S, Kobayashi M, Akuta N, Someya T, Koyama R, Hosaka T. Long-term outcome after interferon therapy in elderly patients with chronic hepatitis C. Intervirology. 2007;50:16-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hoofnagle JH, Seeff LB. Peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2444-2451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Poordad F, McCone J, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, Sulkowski MS, Jacobson IM, Reddy KR, Goodman ZD, Boparai N. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1195-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1996] [Cited by in RCA: 1981] [Article Influence: 141.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, Di Bisceglie AM, Reddy KR, Bzowej NH, Marcellin P, Muir AJ, Ferenci P, Flisiak R. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1905] [Cited by in RCA: 1854] [Article Influence: 132.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Poynard T, Afdhal NH. Perspectives on fibrosis progression in hepatitis C: an à la carte approach to risk factors and staging of fibrosis. Antivir Ther. 2010;15:281-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | D’Souza R, Glynn MJ, Ushiro-Lumb I, Feakins R, Domizio P, Mears L, Alsced E, Kumar P, Sabin CA, Foster GR. Prevalence of hepatitis C-related cirrhosis in elderly Asian patients infected in childhood. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:910-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lee MH, Yang HI, Lu SN, Jen CL, You SL, Wang LY, Wang CH, Chen WJ, Chen CJ. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection increases mortality from hepatic and extrahepatic diseases: a community-based long-term prospective study. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:469-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 389] [Cited by in RCA: 426] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Massard J, Ratziu V, Thabut D, Moussalli J, Lebray P, Benhamou Y, Poynard T. Natural history and predictors of disease severity in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2006;44:S19-S24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Thabut D, Le Calvez S, Thibault V, Massard J, Munteanu M, Di Martino V, Ratziu V, Poynard T. Hepatitis C in 6,865 patients 65 yr or older: a severe and neglected curable disease? Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1260-1267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Masarone M, Persico M. Antiviral therapy: why does it fail in HCV-related chronic hepatitis? Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2011;9:535-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Floreani A, Minola E, Carderi I, Ferrara F, Rizzotto ER, Baldo V. Are elderly patients poor candidates for pegylated interferon plus ribavirin in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:549-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gramenzi A, Conti F, Cammà C, Grieco A, Picciotto A, Furlan C, Romagno D, Costa P, Rendina M, Ancarani F. Hepatitis C in the elderly: a multicentre cross-sectional study by the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:674-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tsui JI, Currie S, Shen H, Bini EJ, Brau N, Wright TL. Treatment eligibility and outcomes in elderly patients with chronic hepatitis C: results from the VA HCV-001 Study. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:809-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Poordad F, Lawitz E, Kowdley KV, Cohen DE, Podsadecki T, Siggelkow S, Heckaman M, Larsen L, Menon R, Koev G. Exploratory study of oral combination antiviral therapy for hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:45-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gane EJ, Stedman CA, Hyland RH, Ding X, Svarovskaia E, Symonds WT, Hindes RG, Berrey MM. Nucleotide polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:34-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 572] [Cited by in RCA: 564] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sarrazin C, Berg T, Ross RS, Schirmacher P, Wedemeyer H, Neumann U, Schmidt HH, Spengler U, Wirth S, Kessler HH. [Prophylaxis, diagnosis and therapy of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection: the German guidelines on the management of HCV infection]. Z Gastroenterol. 2010;48:289-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | European Association for Study of Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2014;60:392-420. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Röder C, Jordan S, Hoepner L, Pudelski N, Supplieth M, Lohse AW, Schulze zur Wiesch J, Lüth S. Hepatitis C Infektion - Herausforderung Alter. Z Gastroenterol. 2012;50:4-45. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Huang CF, Yang JF, Dai CY, Huang JF, Hou NJ, Hsieh MY, Lin ZY, Chen SC, Hsieh MY, Wang LY. Efficacy and safety of pegylated interferon combined with ribavirin for the treatment of older patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:751-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Nudo CG, Wong P, Hilzenrat N, Deschênes M. Elderly patients are at greater risk of cytopenia during antiviral therapy for hepatitis C. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:589-592. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Zheng YY, Fan XH, Wang LF, Tian D, Huo N, Lu HY, Wu CH, Xu XY, Wei L. Efficacy of pegylated interferon-alpha-2a plus ribavirin for patients aged at least 60 years with chronic hepatitis C. Chin Med J (Engl). 2012;125:1852-1856. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Nishikawa H, Iguchi E, Koshikawa Y, Ako S, Inuzuka T, Takeda H, Nakajima J, Matsuda F, Sakamoto A, Henmi S. The effect of pegylated interferon-alpha2b and ribavirin combination therapy for chronic hepatitis C infection in elderly patients. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Alessi N, Freni MA, Spadaro A, Ajello A, Turiano S, Migliorato D, Ferraù O. Efficacy of interferon treatment (IFN) in elderly patients with chronic hepatitis C. Infez Med. 2003;11:208-212. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Antonucci G, Longo MA, Angeletti C, Vairo F, Oliva A, Comandini UV, Tocci G, Boumis E, Noto P, Solmone MC. The effect of age on response to therapy with peginterferon alpha plus ribavirin in a cohort of patients with chronic HCV hepatitis including subjects older than 65 yr. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1383-1391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Gramenzi A, Conti F, Felline F, Cursaro C, Riili A, Salerno M, Gitto S, Micco L, Scuteri A, Andreone P. Hepatitis C Virus-related chronic liver disease in elderly patients: an Italian cross-sectional study. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:360-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Yu ML, Chuang WL. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in Asia: when East meets West. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:336-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, Lok AS. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2762] [Cited by in RCA: 3247] [Article Influence: 147.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Hüppe D, Zehnter E, Mauss S, Böker K, Lutz T, Racky S, Schmidt W, Ullrich J, Sbrijer I, Heyne R. [Epidemiology of chronic hepatitis C in Germany--an analysis of 10,326 patients in hepatitis centres and outpatient units]. Z Gastroenterol. 2008;46:34-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Niederau C, Hüppe D, Zehnter E, Möller B, Heyne R, Christensen S, Pfaff R, Theilmeier A, Alshuth U, Mauss S. Chronic hepatitis C: treat or wait? Medical decision making in clinical practice. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1339-1347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 43. | Poethko-Müller C, Zimmermann R, Hamouda O, Faber M, Stark K, Ross RS, Thamm M. [Epidemiology of hepatitis A, B, and C among adults in Germany: results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56:707-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Ikeda K, Arase Y, Kawamura Y, Yatsuji H, Sezaki H, Hosaka T, Akuta N, Kobayashi M, Saitoh S, Suzuki F. Necessities of interferon therapy in elderly patients with chronic hepatitis C. Am J Med. 2009;122:479-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Jacobson IM, Pawlotsky JM, Afdhal NH, Dusheiko GM, Forns X, Jensen DM, Poordad F, Schulz J. A practical guide for the use of boceprevir and telaprevir for the treatment of hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19 Suppl 2:1-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Butt AA, Kanwal F. Boceprevir and telaprevir in the management of hepatitis C virus-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:96-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Gentile I, Borgia F, Zappulo E, Buonomo AR, Spera AM, Castaldo G, Borgia G. Efficacy and Safety of Sofosbuvir in Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C: The Dawn of the a New Era. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2013;Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Jacobson IM, Gordon SC, Kowdley KV, Yoshida EM, Rodriguez-Torres M, Sulkowski MS, Shiffman ML, Lawitz E, Everson G, Bennett M. Sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 in patients without treatment options. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1867-1877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 846] [Cited by in RCA: 838] [Article Influence: 69.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, Rodriguez-Torres M, Hassanein T, Gordon SC, Schultz M, Davis MN, Kayali Z, Reddy KR. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1878-1887. [PubMed] |