Published online Aug 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10537

Revised: March 12, 2014

Accepted: April 30, 2014

Published online: August 14, 2014

Processing time: 245 Days and 0.6 Hours

AIM: To investigate the impact of prognostic nutritional index (PNI) on the postoperative complications and long-term outcomes in gastric cancer patients undergoing total gastrectomy.

METHODS: The data for 386 patients with gastric cancer were extracted and analyzed between January 2003 and December 2008 in our center. The patients were divided into two groups according to the cutoff value of the PNI: those with a PNI ≥ 46 and those with a PNI < 46. Clinicopathological features were compared between the two groups and potential prognostic factors were analyzed. The relationship between postoperative complications and PNI was analyzed by logistic regression. The univariate and multivariate hazard ratios were calculated using the Cox proportional hazard model.

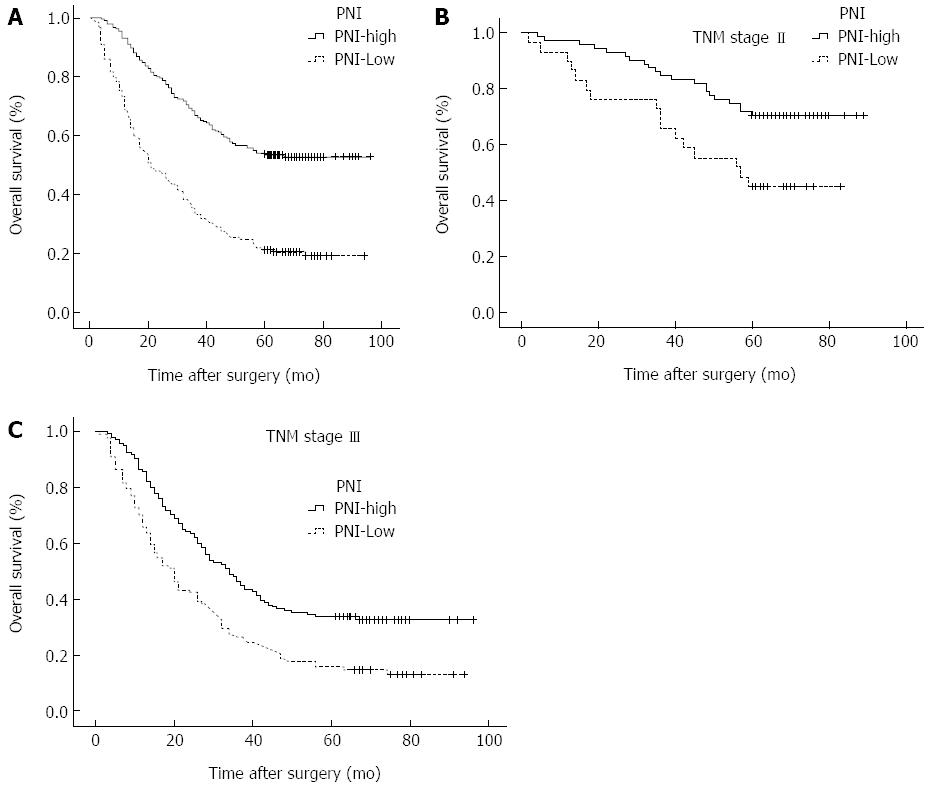

RESULTS: The optimal cutoff value of the PNI was set at 46, and patients with a PNI ≥ 46 and those with a PNI < 46 were classified into PNI-high and PNI-low groups, respectively. Patients in the PNI-low group were more likely to have advanced tumor (T), node (N), and TNM stages than patients in the PNI-high group. The low PNI is an independent risk factor for the incidence of postoperative complications (OR = 2.223). The 5-year overall survival (OS) rates were 54.1% and 21.1% for patients with a PNI ≥ 46 and those with a PNI < 46, respectively. The OS rates were significantly lower in the PNI-low group than in the PNI-high group among patients with stages II (P = 0.001) and III (P < 0.001) disease.

CONCLUSION: The PNI is a simple and useful marker not only to identify patients at increased risk for postoperative complications, but also to predict long-term survival after total gastrectomy. The PNI should be included in the routine assessment of advanced gastric cancer patients.

Core tip: Prognostic nutritional index (PNI) has been shown to be associated with poor outcomes in various types of malignancy. The low PNI was an independent risk factor for the incidence of postoperative complications and an independent predictor of poor overall survival (OS) in gastric cancer patients undergoing total gastrectomy. The OS rates were significantly lower in the PNI-low group than in the PNI-high group among patients with stages II and III disease. We suggest that PNI is a simple and useful marker not only to identify patients at increased risk for postoperative complications, but also to predict long-term survival after total gastrectomy.

- Citation: Jiang N, Deng JY, Ding XW, Ke B, Liu N, Zhang RP, Liang H. Prognostic nutritional index predicts postoperative complications and long-term outcomes of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(30): 10537-10544

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i30/10537.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10537

Malnutrition is usually associated with humoral and cellular immune dysfunction, inflammatory response alterations, and a delay or failure of the wound healing process. Thus, patients with gastric cancer often have a high incidence of serious complications[1,2]. Although surgical resection is the mainstay of curative treatment for gastric cancer, total gastrectomy is associated with postoperative catabolism, and changes in the metabolic, endocrine, neuroendocrine, and immune systems that contribute to high postoperative morbidity rates[3,4]. Therefore, accurately predicting the prognosis is needed to improve patient survival and to provide important information to the patients.

The prognostic nutritional index (PNI), which is calculated based on the serum albumin concentration and total lymphocyte count in the peripheral blood, was originally proposed to assess the perioperative immunenutritional status and surgical risk in patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery[5]. The preoperative nutritional status has been demonstrated to be associated not only with the incidence of postoperative complications, but also with the long-term outcomes of patients with malignant tumors[6-8]. With regard to gastric cancer, however, only a few such studies have been performed, and the clinical significance and prognostic value of this marker remain uncertain[9,10].

Therefore, the primary aim of the study was to assess the impact of perioperative immunonutrition status on postoperative complications and long-term outcomes in gastric cancer patients submitted to total gastrectomy.

A total of 581 patients with gastric cancer underwent total gastrectomy at Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital between January 2003 and December 2008 and were entered into a prospectively maintained database. The inclusion criteria included: (1) patients who underwent a potentially curative resection (R0); (2) patients who underwent a lymphadenectomy (D2 or D3); and (3) patients whose number of dissected lymph nodes were no less than 15. The exclusion criteria included: (1) patients who underwent palliative surgery; (2) patients who did not undergo node dissection (D0); (3) patients who had para-aortic lymph node metastasis; and (4) patients who had distant metastasis or peritoneal dissemination that was confirmed during the operation. Based on these criteria, 195 patients out of 581 were excluded from this study. Of those excluded cases, 97 had less than 15 lymph nodes harvested for pathological examination, 51 had undergone a palliative gastrectomy, 32 had D0 or D1 lymph node resection, 10 had distant metastasis before the gastrectomy, and 5 had peritoneal dissemination before gastrectomy. Therefore, a total of 386 patients were analyzed in this study, including 259 males and 127 females, with a median age of 60 (range: 20-80) years. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

The clinicopathological characteristics were obtained retrospectively from the medical records and evaluated as prognostic factors; these included the patient age, gender, body mass index (BMI), bleeding, tumor size, Borrmann type, histology, extranodal metastasis, serosal invasion, lymph node metastasis, TNM stage and postoperative complication. The stage of gastric cancer was classified according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM classification system[11]. We also collected data from blood tests just before the operation, including the level of serum albumin and total lymphocyte count in the peripheral blood. Then, PNI was calculated using the following formula: 10 × serum albumin value (g/dL) + 0.005 × total lymphocyte count in the peripheral blood (per mm3)[5]. The incidence of postoperative complications (postoperative complications were defined as any deviation from the normal postoperative course) also was evaluated in the present study.

The patients were followed every 3 mo up to 2 years after surgery, then every 6 mo up to 5 years, and thereafter every year or until death. Physical examination, laboratory tests, imaging and endoscopy were performed at each visit. The median follow-up was 39 (range: 1-103) mo, and the last follow-up date was December 20, 2013. The overall survival rate was calculated from the day of surgical resection until time of death or final follow-up.

To evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of the PNI for predicting the 5-year overall survival (OS), the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was calculated, and the Youden index was estimated to determine the optimal cutoff value for the PNI. All patients were divided into two groups according to the cutoff value of the PNI. The clinicopathological characteristics between the two groups were compared using the χ2 test. The survival curves were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences between the curves were analyzed by the log-rank test. The univariate and multivariate hazard ratios were calculated using the Cox proportional hazard model. All significant variables in the univariate analysis were entered into a multivariate analysis. All reported P-values were two-sided. P < 0.05 was considered significant, and CIs were calculated at the 95 % level. The statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software program, version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Using the 5-year survival rate as an endpoint, the area under the ROC curve for the PNI was 0.663. When the PNI was 45.95, the Youden index was maximal. Therefore, the cutoff value of the PNI was set at 46. Then, patients with a PNI ≥ 46 and those with a PNI < 46 were classified into the PNI-high and PNI-low groups, respectively.

There were no statistical differences in gender, tumor location, Borrmann type, bleeding and histology between the two groups. The patients aged 65 years or older and those with a BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 were frequent in PNI-low group. The incidence of postoperative complications and the ratio of tumors with a diameter ≥ 5 cm increased when the PNI was high. Patients with positive extranodal metastasis were more frequently included in the PNI-low group. Patients in the PNI-low group were more likely to have advanced tumor (T), node (N), and TNM stages than patients in the PNI-high group (Table 1).

| Characteristic | PNI-high (n = 245) | PNI-low (n = 141) | χ2 | P value |

| Age (yr) | 5.456 | 0.019 | ||

| < 65 | 168 (68.6) | 80 (56.7) | ||

| ≥ 65 | 77 (31.4) | 61 (43.3) | ||

| Gender | 1.592 | 0.207 | ||

| Female | 75 (30.6) | 52 (36.9) | ||

| Male | 170 (69.4) | 89 (63.1) | ||

| Tumor location | 3.544 | 0.315 | ||

| Upper 1/3 | 80 (32.7) | 39 (27.7) | ||

| Middle 1/3 | 26 (10.6) | 20 (14.2) | ||

| Lower 1/3 | 114 (46.5) | 61 (43.3) | ||

| 2/3 or more | 25 (10.2) | 21 (14.9) | ||

| BMI | 10.348 | 0.001 | ||

| < 18.5 kg/m2 | 31 (12.7) | 36 (25.5) | ||

| ≥ 18.5 kg/m2 | 214 (87.3) | 105 (74.5) | ||

| Bleeding | 0.677 | 0.411 | ||

| ≤ 200 mL | 99 (40.4) | 51 (36.2) | ||

| > 200 mL | 146 (59.6) | 90 (63.8) | ||

| Tumor size | 11.628 | 0.001 | ||

| < 5 cm | 107 (43.7) | 38 (26.2) | ||

| ≥ 5 cm | 138 (56.6) | 103 (73.8) | ||

| Borrmann type | 0.720 | 0.396 | ||

| I/II | 94 (38.4) | 48 (34.0) | ||

| III/IV | 151 (61.6) | 93 (66.0) | ||

| Histology | 0.610 | 0.435 | ||

| Differentiated | 68 (27.8) | 34 (24.1) | ||

| Undifferentiated | 177 (72.2) | 107 (75.9) | ||

| Extranodal metastasis | 4.155 | 0.042 | ||

| Positive | 37 (15.1) | 33 (23.4) | ||

| Negative | 208 (84.9) | 108 (76.6) | ||

| Serosal invasion | 4.257 | 0.039 | ||

| Yes | 189 (77.1) | 121 (85.8) | ||

| No | 56 (22.9) | 20 (14.2) | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | 18.913 | < 0.001 | ||

| pN0 | 90 (36.7) | 34 (24.1) | ||

| pN1 | 41 (16.7) | 17 (12.1) | ||

| pN2 | 56 (22.9) | 27 (19.1) | ||

| pN3 | 58 (23.7) | 63 (44.7) | ||

| TNM stage | 6.859 | 0.032 | ||

| I | 29 (11.8) | 10 (7.1) | ||

| II | 71 (29.0) | 29 (20.6) | ||

| III | 145 (59.2) | 102 (73.2) | ||

| Postoperative complications | 12.391 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 39 (15.9) | 44 (31.2) | ||

| No | 205 (84.1) | 97 (68.8) |

Postoperative complications occurred in 44 (31.2%) of 141 patients with a PNI < 46 compared with 39 (15.9%) of 245 patients with a PNI ≥ 46 (Table 2). In univariate analysis, PNI < 46, bleeding > 200 mL, tumor size ≥ 5 cm, serosal invasion, and lymph node metastasis were significantly associated with postoperative complications. In multivariate analysis, PNI < 46 (OR = 2.223, P = 0.002), bleeding > 200 mL and serosal invasion were independently associated with the incidence of postoperative complications.

| Variable | No. of complications | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| χ2 | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Age ≥ 65 yr | 24 (28.9) | 2.151 | 0.142 | ||

| Gender (male) | 52 (62.7) | 0.948 | 0.330 | ||

| Tumor location (Upper 1/3) | 32 (38.6) | 4.189 | 0.242 | ||

| BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 | 15 (18.1) | 0.038 | 0.846 | ||

| PNI < 46 | 44 (53.0) | 12.391 | < 0.001 | 2.223 (1.344-3.676) | 0.002 |

| Bleeding > 200 mL | 60 (72.3) | 5.532 | 0.019 | 1.762 (1.023-3.037) | 0.041 |

| Tumor size ≥ 5 cm | 60 (72.3) | 4.162 | 0.041 | 1.147 (0.646-2.037) | 0.640 |

| Borrmann type III/IV | 57 (68.7) | 1.357 | 0.244 | ||

| Histological type (undifferentiated) | 63 (75.9) | 0.295 | 0.587 | ||

| Extranodal metastasis (positive) | 14 (16.9) | 0.114 | 0.735 | ||

| Serosal invasion (yes) | 76 (91.6) | 8.471 | 0.004 | 2.792 (1.218-6.404) | 0.015 |

| Lymph node metastasis (pN3) | 40 (48.2) | 14.282 | 0.003 | 1.111 (0.889-1.390) | 0.354 |

| TNM stage (III) | 60 (72.3) | 4.432 | 0.109 | ||

The 5-year OS rate was 54.1% in the PNI-high group and 21.1% in the PNI-low group (P < 0.001; Figure 1A). Results of univariate analysis of postoperative survival showed that tumour size and location, BMI, bleeding, histology and nodal metastasis, but not age, gender, Borrmann type, or chemotherapy, were associated with postoperative survival. Multivariate analyses revealed that PNI (OR = 2.074; 95%CI: 1.581-2.722; P < 0.001) was an independent factor associated with postoperative survival (Table 3). The 5-year OS rate of the patients with stage I disease was 90.6% in the PNI-high group and 71.4% in the PNI-low group (χ2=1.340, P = 0.247). The 5-year OS rate of the patients with stage II disease was 72.9% in the PNI-high group and 40.0% in the PNI-low group (χ2 = 11.591, P = 0.001; Figure 1B). The 5-year OS rate of the patients with stage III disease was 36.6% in the PNI-high group and 12.4 % the in PNI-low group (χ2 = 33.020, P < 0.001; Figure 1C).

| Characteristic | n | 5-yr OS | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| χ2 | Pvalue | HR (95%CI) | Pvalue | |||

| Age (yr) | 3.753 | 0.053 | ||||

| < 65 | 248 | 44.4 | ||||

| ≥ 65 | 138 | 37.0 | ||||

| Gender | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Female | 127 | 41.7 | ||||

| Male | 259 | 41.7 | ||||

| Tumor location | 9.998 | 0.019 | ||||

| Upper 1/3 | 119 | 35.5 | ||||

| Middle 1/3 | 46 | 47.8 | ||||

| Lower 1/3 | 175 | 48.6 | ||||

| 2/3 or more | 461 | 28.3 | ||||

| BMI | 11.744 | 0.001 | 1.405 (1.021-1.935) | 0.037 | ||

| < 18.5 kg/m2 | 67 | 26.9 | ||||

| ≥ 18.5 kg/m2 | 319 | 44.8 | ||||

| Bleeding | 11.786 | 0.001 | 1.346 (1.018-1.780) | 0.037 | ||

| ≤ 200 mL | 150 | 51.3 | ||||

| > 200 mL | 236 | 35.6 | ||||

| Tumor size | 27.632 | < 0.001 | ||||

| < 5 cm | 144 | 57.6 | ||||

| ≥ 5 cm | 242 | 32.2 | ||||

| Borrmann type | 1.613 | 0.204 | ||||

| I/II | 142 | 46.5 | ||||

| III/IV | 244 | 38.9 | ||||

| Histology | 4.831 | 0.028 | ||||

| Differentiated | 102 | 51.0 | ||||

| Undifferentiated | 284 | 38.4 | ||||

| Extranodal metastasis | 17.018 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Positive | 70 | 45.6 | ||||

| Negative | 316 | 24.3 | ||||

| Serosal invasion | 30.363 | < 0.001 | 1.736 (1.115-2.703) | 0.015 | ||

| Yes | 310 | 69.7 | ||||

| No | 76 | 34.8 | ||||

| Lymph node metastasis | 131.31 | < 0.001 | 1.685 (1.487-1.908) | < 0.001 | ||

| pN0 | 124 | 71.8 | ||||

| pN1 | 58 | 46.6 | ||||

| pN2 | 83 | 36.1 | ||||

| pN3 | 121 | 12.4 | ||||

| TNM stage | 78.584 | < 0.001 | ||||

| I | 39 | 84.6 | ||||

| II | 100 | 63.0 | ||||

| III | 247 | 26.3 | ||||

| Postoperative complications | 15.175 | < 0.001 | 1.453 (1.079-1.956) | 0.014 | ||

| Yes | 83 | 22.9 | ||||

| No | 303 | 46.9 | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 2.750 | 0.097 | ||||

| Yes | 224 | 48.1 | ||||

| No | 162 | 37.1 | ||||

| PNI | 2.074 (1.581-2.722) | < 0.001 | ||||

| High | 245 | 54.1 | 60.703 | < 0.001 | ||

| Low | 141 | 21.1 | ||||

Nutritional status resulting from intake, absorption and use of nutrients is particularly influenced by physiological and pathological status[12]. It is well-know that malnutrition is a factor that is closely associated with the incidence of postoperative complications, length of hospital stay, short OS, quality of life and increased mortality of malignant tumors[13,14]. A large multicenter study[15] found that cancer was associated with increased malnutrition rates, and patients’ nutritional status was significantly related to the presence of cancer. Although surgical resection is the mainstay of curative treatment for gastric cancer, total gastrectomy is associated with postoperative catabolism, and changes in the metabolic, endocrine, neuroendocrine, and immune systems that contribute to high postoperative morbidity rates[2]. Malnutrition and major surgery in gastric cancer patients are well-known factors capable of impairing the immunological functions, contributing to an increased risk of postoperative infectious, anastomotic trouble, and metastasis after surgery[16]. The simplified PNI used in our study to assess the immune status was based on two simple laboratory parameters, albumin and absolute lymphocyte count, which are measured routinely in clinical practice.

The PNI was initially designed to assess the nutritional and immunological statuses of patients who underwent gastrointestinal surgery[17]. Previous studies have reported an impact of the PNI on prognosis in several malignancies. Pinato et al[18] found that PNI was useful for assessing survival in patients with hepatocellular cancer. Similar results were reported for patients receiving chemotherapy for advanced colorectal cancer. Mohri et al[7] demonstrated that preoperative PNI is a useful predictor of postoperative complications and survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Yao et al[19] showed that PNI, an indicator of nutritional status that is simple to construct from laboratory parameters, is a useful predictor of the long-term outcome of malignant pleural mesothelioma. However, the optimal cutoff value of the PNI to predict the long-term outcomes remains unclear. Nozoe et al[20] demonstrate that the preoperative PNI value can provide useful information regarding the clinical outcomes of patients with gastric carcinoma, and the mean value of the PNI (49.7) among the study population was set as the border value to divide high and low PNI groups. Migita et al[10] showed that the cutoff value was set at 48, because when the PNI was 48, its sensitivity and specificity for predicting the 5-year OS were 82.3% and 57.9 %, respectively. In the present study, we performed a ROC curve analysis, and the optimal cutoff value for the PNI was determined to be 46. When the PNI was 46, the Youden index was maximal. We saw a close correlation between PNI and age, BMI, tumor size, histology, which was consistent with the finding by Watanabe et al[9] who observed that PNI in younger patients undergoing gastrectomy is significantly higher than that in older patients. In our study, the percentage of patients aged 65 years or older was higher in the PNI-low group than in the PNI-high group (P = 0.019). Many studies had demonstrated that advanced age is an independent adverse predictor of survival for cancer patients[21,22], but we failed to find the relationship between prognosis and age in our study cohort. The present study demonstrated that the PNI was significantly lower in patients with features of more advanced tumors, such as deeper depth of invasion and positive lymph node metastasis, than in those without such factors. The PNI was associated with a higher risk of postoperative complications of gastric cancer. Mohri et al[7] reported that PNI was an independent predictor of postoperative complications in patients with colorectal cancer. Therefore, although PNI was initially thought of purely as a reflection of the nutritional status of a patient, given that its prognostic association is likely, PNI is a reflection of postoperative complications. Previous studies demonstrated that the development of postoperative complications, such as anastomotic leakage, had a negative impact on the gastric cancer prognosis[23,24], and some studies have shown that perioperative immunonutrition significantly reduces the postoperative complications and length of hospital stay[16,25]. Our results suggest that postoperative complications occurred more frequently in the PNI-low group than in the PNI-high group, and the multivariate analysis demonstrated that preoperative PNI, easily measurable before surgery, may be used clinically to identify patients at increased risk for postoperative complications (OR = 2.223, P = 0.002). These results are consistent with several previous studies evaluating the predictive role of PNI in malignancies[10,18,26].

Several studies have reported the tumor location, macroscopic and histological types of the tumor, tumor size, tumor depth, lymph node involvement, distant metastasis, and curability are associated with the prognosis for gastric cancer patients undergoing total gastrectomy[27,28]. Our present study demonstrated that the OS rate of the PNI-low group was significantly lower than that of the PNI-high group, and the 5-year OS rates were 54.1% and 21.1%, respectively, possibly due to tumor progression and decreased oral intake as a result of the cancer. Takushima et al[29] demonstrated that a lower PNI value was an indicator for a poor prognosis in patients with gynecological tumors. Nozoe et al[26] reported that the preoperative PNI value can provide useful information regarding the clinical outcomes of patients with colorectal carcinoma. The survival rate of patients with a lower PNI value was also significantly lower than that of patients with a higher PNI value. The multivariate analysis performed in the present study demonstrated that PNI had prognostic value similar to that of lymph node metastasis and serosal invasion and a lower value of PNI was independently associated with a more unfavorable prognosis of patients with gastric carcinoma. In the stratified analysis, the PNI-low group had a significantly lower OS rate than the PNI high group among patients with stages II and III disease, while there was no difference between the PNI-high group and PNI-low group with stage I. These results may suggest that a low PNI effects a preoperative low immunonutritional status that decreases the body immune system against tumors and increases the tumor burden, which leads to the growth of residual tumor cells, and is associated with a worse prognosis in advanced cancer after total gastrectomy.

Although the mechanism or mechanisms behind postoperative complication with poor long-term prognosis after cancer resection and a larger sample size, randomized prospective cohorts, multicenter studies to evaluate the prognostic effect of PNI and identify the underlying mechanism remain to be determined. Despite that, PNI < 46 was an independent predictor of severe postoperative complications and long-term survival after total gastrectomy.

In conclusion, our results suggest that preoperative PNI, easily measured before surgery, may be used clinically not only to identify patients at increased risk for postoperative complications, but also to predict long-term survival after surgery as a simple and useful marker. We suggest that PNI should be included in the routine assessment of gastric cancer patients undergoing total gastrectomy. Physicians should pay attention to perioperative care for patients with a low PNI value.

Prognostic nutritional index (PNI) had been demonstrated to be associated not only with the incidence of postoperative complications, but also with the long-term outcomes of patients with malignant tumors. However, the relationship between PNI and gastric cancer is still unclear.

Low PNI may result in more postoperative complications and poorer prognosis. Research has shown a negative association between PNI and prognosis of many malignancies. Few researchers have focused on PNI during resection of gastric cancer. In this study, authors demonstrated that PNI can be used clinically not only to identify patients at increased risk for postoperative complications, but also to predict long-term survival after surgery as a simple and useful marker.

It is well know that malnutrition is a factor that is closely associated with the incidence of postoperative complications, length of hospital stay, short overall survival, quality of life and increased mortality of malignant tumors. This study confirmed that PNI can be used clinically not only to identify patients at increased risk for postoperative complications, but also to predict long-term survival after total gastrectomy as a simple and useful marker.

By understanding the negative association between PNI and incidence of postoperative complications and the relationship between PNI and prognosis of gastric cancer, this study may stimulate surgeons to pay attention to PNI. PNI should be included in the routine assessment of gastric cancer patients undergoing total gastrectomy.

Postoperative complications were defined as any deviation from the normal postoperative course. Extranodal metastasis was defined as the presence of tumor cells in extramural soft tissue that was discontinuous with either the primary lesion or locoregional lymph nodes.

PNI has been shown to be associated with poor outcomes in various types of malignancy. This study shows that PNI can be used clinically not only to identify patients at increased risk for postoperative complications, but also to predict long-term survival after surgery as a simple and useful marker.

P- Reviewer: Deng JY, Kakushima N, Klaus A, Tovey FI S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Okamoto Y, Okano K, Izuishi K, Usuki H, Wakabayashi H, Suzuki Y. Attenuation of the systemic inflammatory response and infectious complications after gastrectomy with preoperative oral arginine and omega-3 fatty acids supplemented immunonutrition. World J Surg. 2009;33:1815-1821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fujitani K, Tsujinaka T, Fujita J, Miyashiro I, Imamura H, Kimura Y, Kobayashi K, Kurokawa Y, Shimokawa T, Furukawa H. Prospective randomized trial of preoperative enteral immunonutrition followed by elective total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2012;99:621-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Klek S, Sierzega M, Szybinski P, Szczepanek K, Scislo L, Walewska E, Kulig J. The immunomodulating enteral nutrition in malnourished surgical patients - a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Clin Nutr. 2011;30:282-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cuschieri A, Fayers P, Fielding J, Craven J, Bancewicz J, Joypaul V, Cook P. Postoperative morbidity and mortality after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: preliminary results of the MRC randomised controlled surgical trial. The Surgical Cooperative Group. Lancet. 1996;347:995-999. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Onodera T, Goseki N, Kosaki G. [Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery of malnourished cancer patients]. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1984;85:1001-1005. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Nozoe T, Kimura Y, Ishida M, Saeki H, Korenaga D, Sugimachi K. Correlation of pre-operative nutritional condition with post-operative complications in surgical treatment for oesophageal carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:396-400. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Mohri Y, Inoue Y, Tanaka K, Hiro J, Uchida K, Kusunoki M. Prognostic nutritional index predicts postoperative outcome in colorectal cancer. World J Surg. 2013;37:2688-2692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kang SH, Cho KH, Park JW, Yoon KW, Do JY. Onodera’s prognostic nutritional index as a risk factor for mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:1354-1358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Watanabe M, Iwatsuki M, Iwagami S, Ishimoto T, Baba Y, Baba H. Prognostic nutritional index predicts outcomes of gastrectomy in the elderly. World J Surg. 2012;36:1632-1639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Migita K, Takayama T, Saeki K, Matsumoto S, Wakatsuki K, Enomoto K, Tanaka T, Ito M, Kurumatani N, Nakajima Y. The prognostic nutritional index predicts long-term outcomes of gastric cancer patients independent of tumor stage. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2647-2654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sano T. [Evaluation of the gastric cancer treatment guidelines of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2010;37:582-586. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Andreoli A, De Lorenzo A, Cadeddu F, Iacopino L, Grande M. New trends in nutritional status assessment of cancer patients. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2011;15:469-480. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Morgan TM, Tang D, Stratton KL, Barocas DA, Anderson CB, Gregg JR, Chang SS, Cookson MS, Herrell SD, Smith JA. Preoperative nutritional status is an important predictor of survival in patients undergoing surgery for renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2011;59:923-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lee H, Cho YS, Jung S, Kim H. Effect of nutritional risk at admission on the length of hospital stay and mortality in gastrointestinal cancer patients. Clin Nutr Res. 2013;2:12-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Porbén SS. The state of the provision of nutritional care to hospitalized patients--results from The Elan-Cuba Study. Clin Nutr. 2006;25:1015-1029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Xu J, Zhong Y, Jing D, Wu Z. Preoperative enteral immunonutrition improves postoperative outcome in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. World J Surg. 2006;30:1284-1289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Smale BF, Mullen JL, Buzby GP, Rosato EF. The efficacy of nutritional assessment and support in cancer surgery. Cancer. 1981;47:2375-2381. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Pinato DJ, North BV, Sharma R. A novel, externally validated inflammation-based prognostic algorithm in hepatocellular carcinoma: the prognostic nutritional index (PNI). Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1439-1445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yao ZH, Tian GY, Wan YY, Kang YM, Guo HS, Liu QH, Lin DJ. Prognostic nutritional index predicts outcomes of malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:2117-2123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Nozoe T, Ninomiya M, Maeda T, Matsukuma A, Nakashima H, Ezaki T. Prognostic nutritional Index: A tool to predict the biological aggressiveness of gastric carcinoma. Surg Today. 2010;40:440-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Borasio P, Berruti A, Billé A, Lausi P, Levra MG, Giardino R, Ardissone F. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: clinicopathologic and survival characteristics in a consecutive series of 394 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:307-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bagheri R, Haghi SZ, Rahim MB, Attaran D, Toosi MS. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: clinicopathologic and survival characteristic in a consecutive series of 40 patients. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17:130-136. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Sierzega M, Kolodziejczyk P, Kulig J. Impact of anastomotic leakage on long-term survival after total gastrectomy for carcinoma of the stomach. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1035-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yoo HM, Lee HH, Shim JH, Jeon HM, Park CH, Song KY. Negative impact of leakage on survival of patients undergoing curative resection for advanced gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:734-740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Braga M, Gianotti L, Vignali A, Carlo VD. Preoperative oral arginine and n-3 fatty acid supplementation improves the immunometabolic host response and outcome after colorectal resection for cancer. Surgery. 2002;132:805-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Nozoe T, Kohno M, Iguchi T, Mori E, Maeda T, Matsukuma A, Ezaki T. The prognostic nutritional index can be a prognostic indicator in colorectal carcinoma. Surg Today. 2012;42:532-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lee MS, Lee JH, Park do J, Lee HJ, Kim HH, Yang HK. Comparison of short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy and open total gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2598-2605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Feng J, Wu YF, Xu HM, Wang SB, Chen JQ. Prognostic significance of the metastatic lymph node ratio in T3 gastric cancer patients undergoing total gastrectomy. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:3289-3292. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Takushima Y, Abe H, Yamashita S. [Evaluation of prognostic nutritional index (PNI) as a prognostic indicator in multimodal treatment for gynecological cancer patients]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1994;21:679-682. [PubMed] |