Published online Aug 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i29.10008

Revised: March 4, 2014

Accepted: April 8, 2014

Published online: August 7, 2014

Processing time: 239 Days and 13.7 Hours

Since the first description of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) of the pancreas in the eighties, their identification has dramatically increased in the last decades, hand to hand with the improvements in diagnostic imaging and sampling techniques for the study of pancreatic diseases. However, the heterogeneity of IPMNs and their malignant potential make difficult the management of these lesions. The objective of this review is to identify the molecular characteristics of IPMNs in order to recognize potential markers for the discrimination of more aggressive IPMNs requiring surgical resection from benign IPMNs that could be observed. We briefly summarize recent research findings on the genetics and epigenetics of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, identifying some genes, molecular mechanisms and cellular signaling pathways correlated to the pathogenesis of IPMNs and their progression to malignancy. The knowledge of molecular biology of IPMNs has impressively developed over the last few years. A great amount of genes functioning as oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes have been identified, in pancreatic juice or in blood or in the samples from the pancreatic resections, but further researches are required to use these informations for clinical intent, in order to better define the natural history of these diseases and to improve their management.

Core tip: The heterogeneity and the malignant potential of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms make their management still controversial. The identification of potential markers correlated to the pathogenesis of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and with their progression to malignancy could be useful to discriminate lesions requiring surgical resection from benign neoplasms that could be followed-up.

- Citation: Paini M, Crippa S, Partelli S, Scopelliti F, Tamburrino D, Baldoni A, Falconi M. Molecular pathology of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(29): 10008-10023

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i29/10008.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i29.10008

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) are one of the most fascinating pancreatic neoplasm to be characterized in the last few decades. Described for the first time by Ohashi et al[1] in 1982 as a separate tumor from mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs) and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA), they were confused or misdiagnosed with MCNs for many years. It is now clear that these two mucin-producing neoplasms are clearly separate entities. MCNs are characteristically defined by an ovarian-like stroma, they do not arise from the ductal system of the pancreas and they are single lesions located almost exclusively in the pancreatic body-tail of middle-aged women[2,3]. IPMNs are mucin-producing neoplasms, arising from the native pancreatic ducts with prominent intraductal growth and frequent papillary architecture[4]. Although the true incidence of IPMNs is unknown, these neoplasms are nowadays frequently recognized because of the widespread use of cross-sectional imaging and because of the greater awareness of this entity among radiologists, gastroenterologists and surgeons[5,6]. Data from high-volume centers for pancreatic surgery suggest that about 15% to 20% of all pancreatectomies are performed for IPMN[7]. Interestingly, in an autopsy study, small cystic lesions possibly representing IPMNs were found in 24% of elderly patients[8]. As our understanding of IPMNs has grown over time, it has become clear that IPMNs are a heterogeneous group of tumors, with different clinical and radiological presentation, different risk of malignancy and different management. In this light, it is important the preoperative prediction of the malignant potential of an IPMN in order to balance the potential complications of pancreatic surgery with the potential risk of being or become malignant over time. Hence, for a better and complete decision making, it is important to consider also the molecular pathology of IPMNs to identify molecular markers of “high-risk” lesions. Nevertheless, the information we have about molecular mechanisms involved in their carcinogenesis is still poor. The aim of this review is to present the role of the oncogenic and the tumor suppressor pathways in the neoplastic transformation of IPMNs.

IPMNs can be classified according to the involvement of pancreatic ductal system in[4,9]: (1) main-duct type, when the tumor involves only the main pancreatic duct; (2) branch-duct type, when the tumor involves only branch-ducts, with no macroscopic or microscopic involvement of the main pancreatic duct; and (3) combined type, when the neoplasms involved macroscopically and/or microscopically both the main pancreatic duct and its side branches.

A clear identification and distinction of main-duct, combined and branch-duct IPMNs is not only of taxonomic significance, but has a practical impact on patient management. Combined IPMNs show close overlapping similarities with main-duct IPMNs in regard to clinico-pathological and epidemiological characteristics[6]. Moreover, branch-duct IPMNs have a lower risk of malignant degeneration compared to main-duct/combined IPMNs and non-surgical management is feasible for many of these lesions, thus avoiding “prophylactic” pancreatectomy with its associated risks[9-12]. Histologically, IPMNs can be categorized in four groups based on the degree of cytoarchitectural dysplasia[13,14]: (1) IPMN with low-grade dysplasia (IPMN adenoma); (2) IPMN with moderate intermediate-grade dysplasia (IPMN borderline); (3) IPMN with high-grade dysplasia (IPMN with carcinoma in situ); and (4) IPMN with invasive carcinoma (invasive IPMN).

Remarkably, IPMNs may show different degrees of dysplasia within the same lesions. As colonic adenomas, they can show neoplastic transformation culminating in invasive carcinoma. Approximately 15%-20% of branch-duct IPMNs and 40%-50% of main-duct IPMNs harbor an invasive carcinoma[9]. In half of the cases, the invasive carcinoma has a colloid (or muconodular) pattern of invasion, while in the remaining 50% of the cases a tubular (or conventional) ductal pattern is present[14,15]. Tubular-type is morphologically indistinguishable from ordinary PDA. Colloid type is very similar to colloid carcinoma of the breast and it is associated with a good prognosis[15]. Chemotherapy for patients with resected invasive IPMN is recommended[16]; adjuvant treatment is advisable also in case of positive resection margins or lymph node metastases[17]. Moreover, lifetime surveillance is required also for non-invasive IPMN after partial pancreatectomy since the risk of local recurrence in the pancreatic remnant is about 8%-10% and it may be the expression of a new metachrous tumor. The neoplastic epithelial cells in an IPMN can have a variety of directions of differentiation[18]. Histological subtypes of IPMNs include: (1) intestinal type: morphologically it is very similar to colonic villous adenomas. Most main-duct IPMNs are of intestinal type, carrying a higher risk of invasive carcinoma, more commonly of the colloid type; (2) gastric type: virtually indistinguishable from gastric mucosa, it is characterized by a low proliferative activity with a very low risk of malignant transformation. It is the most common subtypes among branch-duct IPMNs; (3) pancreatobiliary type: it is characterized by a complex papillary configuration and it is uncommon. Usually it is associated with at least high-grade dysplasia and it is considered as the high-grade version of gastric type. When invasive carcinoma is present, it is frequently of the tubular type; and (4) oncocytic type: originally described as a separate entity[19], this IPMN subtype shows proliferative cells associated with atypical cytology. It is associated with high-grade dysplasia.

Finally, multifocal lesions can be frequently found in IPMNs. Main-duct IPMNs may involve the entire main pancreatic duct or “skip” lesions can occur with synchronous, multifocal involvement of main duct epithelium[20]. Multifocal IPMNs are frequently found in the branch-duct type and they represent a challenging situation both for IPMNs undergoing surgical resection and for those which are non-operatively managed. The presence of multifocal branch-duct IPMNs does not seem to be associated with an increased risk of malignancy[21].

Kirsten-ras (KRAS) is located on chromosome arm 12p and encodes a membrane-bound guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-binding protein. In some cases the mutation can occur at the codon 13[22]. The frequency of the KRAS gene mutations in IPMNs varies from study to study, ranging from 38.2%[23] to 100%[24-26]. The wide variety of the reported frequencies is most likely due to the ongoing better definition of these lesions[13,18,27] and might also be dependent on the sensitivity of a chosen screening methodology[28]. There is no significant difference among the incidence of KRAS mutation in the various grades of dysplasia: 87% in low-grade, 90.2% in intermediate grade and 70.7% in high-grade dysplasia[29]; anyway, this mutation is considered to be an early event in the neoplastic transformation of IPMNs[30].

The expression of KRAS mutation can be found both in surgically resected specimens, in the peripheral blood[31] and in the pancreatic juice; however, in the latter case, KRAS mutations are not a specific marker for pancreatic neoplasms because similar mutations were detected in the pancreatic juice from patients with chronic pancreatitis or other pancreatic diseases[32,33]. Moreover KRAS mutation is frequently found also in the peritumoral region and in other lesions of IPMN, but only if the mutation is present in the main tumor[30].

Furthermore, a significant difference in the diameter of the main pancreatic duct between patients with and without the mutant KRAS gene was detected; this suggests that the incidence of KRAS mutation may be associated with the hypersecretion of mucin[34]. KRAS mutations have the highest frequency in the pancreatobiliary subtype (100%) and the lowest frequency in the intestinal subtype (46.2%)[29].

GNAS is an oncogene located on the long arm of chromosome 20 at position 13.3, encoding the guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G-protein) alpha subunit (Gs-α)[35]. Mutations at codon 201 were detected in 61% of IPMNs[36]. An important aspect for the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions is that GNAS mutations were not found in cystic neoplasms other than IPMN or in invasive adenocarcinomas not associated with IPMN[29]. The prevalence of GNAS mutations is higher in more advanced lesions, from 19% in low-grade dysplasia, to 23% in intermediate grade and 58% in high-grade dysplasia. As regarding histological subtypes, 100% of the intestinal type harbored GNAS mutations, while 71% of pancreatobiliary type and 51% of gastric type shows mutant GNAS; in oncocytic IPMNs no mutation of GNAS is found[36].

Phosphatidylinositol-3 kinases (PI3Ks) constitute a large and complex family of lipid kinases encompassing three classes with multiple subunits and isoforms[37]. They play an important role in several cellular functions, such as proliferation, differentiation, chemotaxis, survival, trafficking and glucose homeostasis[37]. Phosphoinositide-3-kinase-catalyc-alfa gene (PI3KCA) mutations frequently occur in exon 9 and 20 in more of 75% of the cases, affecting the functionally important helical and kinase domains of the protein[38-40]. Particularly, the mutations E542K, E545K and H1047R seem to elevate the lipid kinase activity of PIK3CA and to activate the Akt signaling pathway. In IPMNs, the frequency of the somatic mutation of the PIK3CA gene is 11%[28]. PIK3CA mutation seems to be a rather late event in the transition of these lesions to malignancy[28,41]. In PDA cell lines no mutation is found in the entire coding region of the PIK3CA gene[38].

B-Raf is a serine/threonin kinase, encoded by BRAF, located immediately downstream in Ras signaling, in the RAS/MAPK pathway that regulates proliferation, differentiation, migration and apoptosis of the cells. The Ras pathway involves the kinase cascade Raf/MEK/ERK; BRAF is one of the three isoforms that Raf shows (the others are a-Raf and c-RAF/Raf-1)[22].

The BRAF gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 7 at position 34. The rate of the somatic BRAF mutation descripted for IPMN is only 2.7%[22,28]. Even if the BRAF mutation is not frequent, the alteration of the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK-MAP kinase pathway by BRAF mutation together with Ras mutation may play an important role in the tumorigenesis of IPMNs[22,28]; it is possible that tumors with both BRAF and KRAS mutations have an accelerated course in the development or progression[28].

Human telomeres are nucleoprotein complexes in the chromosomes ends, essential to genomic stability[42]. When telomeres become critically short, after repeated replication-dependent loss of DNA termini[43] during various cell divisions, loss their capping function and so, protective mechanisms avoid genetic instability, eliminating senescent cells[42]. However, in case of activation of telomerase, the function of telomeres can be restored through the elongation of telomeric DNA sequences and the overcoming of the telomere crisis[44], thus the cells survive with accumulation of multiple genomic and epigenetic aberrations[45]. Telomerase is a RNA-dependent DNA polymerase, generally inactivated in normal human somatic cells. Its catalytic component is encoded by the human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) gene, located on chromosome 5[46,47]. In IPMNs, it is possible to notice a gradual decrease of the telomeres with histologic progression; they are shortened in the 97.3% of the loci analyzed[48]. Telomere shortening can be observed in any case of adenoma, with a 50% reduction in length in half of the foci examined[48]. As in carcinoma in situ IPMNs the telomere shortening is significant compared to borderline IPMNs, but non compared to PDAs, it is likely that telomeres shorten to a critical length at the carcinoma in situ histological grade[48]. Telomerase activity is significantly higher in invasive carcinoma than in borderline or carcinoma in situ. In malignant IPMNs, also hTERT expression is higher than in non-malignant neoplasms: 15.8% in adenoma, 35.7% in borderline, 85% in carcinoma in situ and 86.7% in invasive carcinoma[48]. Then, transition from borderline to carcinoma in situ seems to be the critical step at which telomere dysfunction occurrs during IPMN carcinogenesis; the ability of the cells to overcome this crisis through the up-regulation of hTERT is a promoting event for the development of malignancy[44,45,48].

The hedgehog family consists of three homologous genes: the first two discovered, desert hedgehog (Dhh) and Indian hedgehog (Ihh), were named after species of the spiny mammal, whereas the third, sonic hedgehog (Shh), was named after the character from the popular Sega Genesis video game. Hedgehog (Hh) proteins are a family of secreted signaling factors that regulate the development of many organs and tissues[49]. Shh is the best studied ligand of the Hedgehog signaling pathway; abnormal activation of Hedgehog pathway is described in IPMNs: Shh expression is detected in 46.2% of adenomas, 35.7% of borderline dysplasia IPMNs, 80% of carcinoma in situ-IPMNs and 84.6% of invasive carcinomas with a significant increase in malignant IPMNs[50]. Evaluating IPMN by histological subtype, Shh is expressed in 68.8% of intestinal types, in 92.8% of pancreatobiliary types, 38.1% of null types and in 50% of unclassifiable types[50]. Shh expression is detected also in stromal cells, rarely in adenoma and borderline IPMNs, significantly in malignant IPMNs[50]. In addiction, its expression is showed in tumor cells of metastatic lymph nodes[50].

As Shh expression is detectable in pancreatic juice from IPMN, but it is absent in pancreatitis juice, Shh measurement in pancreatic juice could discriminate IPMN from chronic pancreatitis[51].

These data suggest that the activation of the Shh signaling pathway may be involved in an early stage of the development of IPMN[50-52] and contributes to the transformation from benign to malignant dysplasia in IPMN[52], especially in the intestinal and pancreatobiliary types. Shh expression may also have a role in metastatic progression to lymph node in malignant IPMN[50]. Oncogenes and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms show in Table 1.

| Ref. | Gene symbol | Gene name | Mechanism of genetic alteration | Chromosome site | Known or predicted function | Alteration in IPMN |

| Z’graggen et al[24], 1997 | KRAS2 | v-Ki-ras-2 Kirsten | Point mutation | 12p12.1 | Signal transduction, proliferation, cell survival, motility | 81.2% |

| rat sarcoma | ||||||

| viral oncogene | ||||||

| homolog | ||||||

| Dal Molin et al[36], 2013 | GNAS | GNAS complex locus | Point mutation | 20q13.3 | G-protein beta/gamma-subunit complex binding | 61% |

| Schönleben et al[41], 2006 | PI3KCA | Phosphoinositide-3-kinase | Point mutation | 3q26.3 | Proliferation, differentation, chemotaxis, survival, trafficking, glucose homeostasis | 11% |

| Schönleben et al[22], 2007 | BRAF | v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 | Point mutation | 7q34 | Signal transduction, cell growth | 2.7% |

| Hashimoto et al[48], 2008 | TERT | Telomerase reverse transcriptase | Deletion, | 5p15.3 | Genome stability | 70.6% |

| nonsynonymous mutation, polymorphisms | ||||||

| Jang et al[50], 2007 | SHH | Sonic hedgehog | Point mutation, missense mutation | 7q36 | Cell growth, cell specialization, proliferation of adult stem cells | 61.8% |

CDKN2A is a tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 9p21 (the locus of Ink4A) that encodes the cyclin dependent kinase (Cdk) inhibitor p16Ink4A. This protein inhibits progression of the cell cycle at the G1-S checkpoint (under the control of the Retinoblastoma pathway), binding to cyclin-dependant kinases (CDKs)[53] and provoking Retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation: its loss of function results in the acceleration of cell growth[34,54]. Different mechanisms are responsible of its inactivation, such as homozygous deletion, intragenic mutation and epigenetic silencing by promoter methylation. All of these invalidating modifications arise at late stages of pancreatic carcinogenesis. While the loss of p16 protein described in adenoma/borderline IPMNs varies from 10%[55] to 25%[56], in the IPMN carcinomas the inactivation of the suppressor gene is found in 77.8%[56]-100%[55] of the cases. Observing all the degrees of histological atypia, loss of heterozygosity of the p16 gene was described increasingly from adenoma (12.5%) to IPMNs with intermediate dysplasia (20%), high-grade dysplasia (33%) and invasive carcinoma (100%)[26]. It’s evident that p16 loss is necessary but not sufficient to induce progression from non-invasive IPMN to invasive carcinoma; in any case, loss of p16 alone is considered the strongest marker in differentiating IPMN with low-grade/intermediate dysplasia from the IPMN with carcinoma (in situ or invasive)[55].

The tumor suppressor gene p53 is located on the short arm of chromosome 17p; it regulates an essential growth checkpoint that both protects against genomic rearrangement or accumulation of mutations and suppresses cellular transformation caused by oncogene activation or by the loss of tumor suppressor pathways[57]. The roles of p53 protein are the maintenance of G2-M arrest, the regulation of G1-S checkpoint, the induction of apoptosis and the regulation of senescence, the repair of DNA damages and the change of cellular metabolism[58,59]. p53 gene is inactivated especially by missense mutations in sequences coding for the DNA binding domain[57], through intragenic mutations of allele 1, accompanied with loss of the other allele[60,61]. Even if the percentage of mutated p53 in IPMN is slightly different in the reports, from 27.3%[26] until 42% (in pancreatic juice and in tissue specimens)[62] or 52%[63], the consensus is that in the majority of the cases no mutation of p53 is commonly found in adenoma dysplasia; p53 mutation is detectable in 33.3% of the borderline tumor and in 38.5% of non-invasive carcinoma[64], while in almost all invasive carcinoma p53 gene is inactivated[26,62,65]. Therefore, loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of p53 gene seems to be a relatively late event in the carcinogenesis of IPMN, similarly to what happens in colorectal neoplasms[26,66].

In IPMNs, LOH of the p53 gene concomitant with LOH of the p16 gene are detected in 0% of the adenomas, in 20% of the borderline tumors, in 33% of the non-invasive carcinomas and in all the invasive carcinomas[26,56]; hence, LOH of p16 and p53, and the accumulation of genetic alterations, are crucial events in the evolution of IPMN to an invasive carcinoma[26].

Deleted in pancreatic cancer locus 4 (DPC4) tumor-suppressor gene, located at chromosomal region 18q21, is involved in the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) growth inhibitory pathway. DPC4 encodes SMAD4, a nuclear transcription factor that activates transcription of cell cycle inhibitory factors, particularly p21CIP1[58]. DPC4 is inactivated by homozygous deletion and by intragenic mutations accompanied by loss of the other allele[58,67,68]. As a consequence, loss of function of SMAD4 lead to upregulation of the Retinoblastoma pathway with the consequent progression from G1 to S phase of the cell cycle until the unregulated cellular proliferation[54,55,58]. Inactivation of DPC4 is relatively specific for pancreatic adenocarcinoma (inactivated in the 55% of the cases)[67,69,70]. SMAD4 expression is detected in all adenoma/borderline IPMNs and carcinoma in situ IPMNs, while it is lost in 75% of invasive carcinoma IPMNs[55]. Then, loss of SMAD4 expression is the best marker for the presence of invasive carcinoma[55]. Among invasive carcinomas, all colloid carcinomas seem to show strong and diffuse positive labeling for DPC4, whereas only 50% of tubular carcinomas present intense DPC4 staining[71]. SMAD4 mutations have also recently been associated with poor prognosis and with the development of widespread metastatic disease in pancreatic cancer[72,73].

Serine/threonine kinase 11 gene (STK11) gene, also known as liver kinase B1 (LBK1), on chromosome arm 19p, encodes a serine/threonine kinase with growth-suppressing activity[74]. Furthermore, the product of STK11/LBK1, in association with p53, regulates p53-dependent apoptosis[75]. Inherited mutations in this gene are responsible for most cases of Peutz-Jegher syndrome (PJS) and they are associated with IPMN and PDA[58]. The biallelic inactivation of the STK11/LKB1 gene in IPMN of the patients with PJS suggests a causative relationship between the mutation and IPMN[76,77]. However, in addition to germline mutations, somatic mutations can be found in 5% of patients with sporadic IPMN and pancreatic cancers[76,77]. LOH at 19p13.3 is present in 100% of IPMNs from patients with PJS and in 25% from patients lacking features of PJS[77]. As patients with PJS have a 132-fold increased risk of developing pancreatic cancer (that may develop as an IPMN)[78,79], IPMN can be a “curable precursor” of PDA in some of these patients[79,80].

BRG1, encoded by the gene at chromosomal region 19p13.2, is an ATPase/helicase and constitutes the catalytic subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex, that disrupts the adhesion of histone components and DNA, allowing transcription factors access to their target genes. The tumor suppressive nature of BRG1 has been demonstrated in IPMNs, where the loss of BRG1 expression occurs in 53.3% of the lesions, increasing from the low-grade IPMNs (28%) to intermediate-grade (52%) and to high-grade IPMNs (76%); a progressive loss of BRG1 expression is therefore associated with increasing degree of dysplasia[81]. No significant correlation between BRG1 expression and the various histological subtypes or the different locations within the ductal system of the cyst has been found[81].

Tumor suppressor genes and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms are shown in Table 2.

| Ref. | Gene symbol | Gene name | Mechanism of genetic alteration | Chromosome site | Known or predicted function | Alteration in IPMN |

| Wada et al[26], 2002 | CDKN2A/p16 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A | Homozygous deletion (41%), intragenic mutation (38%) | 9p21 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor | 38.1% |

| Wada et al[26], 2002 | TP53 | Tumor protein p53 | Intragenic mutation in 1 allele and loss in the other allele | 17p13.1 | Cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, senescence, DNA repair, metabolism change | 27.3% |

| Biankin et al[55], 2002 | SMAD4/DPC4 | Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog of 4, drosophila | Homozygous deletion (50%), intragenic mutation in 1 allele and loss in the other allele (50%) | 18q21.1 | Signal transmission | 16.7% |

| Sato et al[77], 2001 | STK11/LKB1 | Serine/threonine kinase 11 | Homozygous deletion, intragenic mutation in 1 allele and loss in the other allele | 19p13.3 | Apoptosis regulation | 32% (100% in patients with PJS and 25% in patients without PJS) |

| Dal Molin et al[81], 2012 | BRG1 | Brahma-related gene-1 | Homozygous deletion, intragenic mutation in 1 allele and loss in the other allele | 19p13.2 | Regulation of cellular proliferation, regulation of several genes involved in key steps in tumorigenesis | 53.3% |

DNA methylation of tumor suppressor gene promoter sites is an epigenetic mechanisms that has been demonstrated to play a role in tumorigenesis[82].

Aberrant hypermethylation of gene promoter regions and subsequent loss of gene expression can be observed in several human neoplasms[83-85]; in particular, aberrant methylation involving at least one gene promoter site is present in 92% of the neoplastic cases[82]. As regarding IPMN, silencing of tumor suppressor gene expression by promoter hypermethylation at cytosine-phospho-guanine (CpG) islands (genomic regions that contain a high frequency of CpG sites, found in about 40% of promoters of mammalian genes) is detectable in more than 80% of samples[86].

Aberrant methylation is present in promoter regions of genes with well-characterized roles in tumor suppression, most frequently of genes implicated in cell cycle control, as p16, APC and p73[82].

Significantly, higher grade IPMNs have more methylated genes than lower grade IPMNs[87]; for instance, IPMNs harbor APC hypermethylation in 10% of non-invasive samples and in 50% of the infiltrative ones[82]. A similar difference is detectable in E-cadherin methylation, the gene related to tissue infiltration and locoregional metastasis (10% in non-invasive IPMNs and 38% in invasive IPMNs)[82]. Also the mismatch repair genes hMLH1 and MGMT are more frequently methylated in the invasive IPMNs than in the non-invasive tumors (38% vs 10% and 45% vs 20%, respectively)[82]. A significant difference in the aberrant methylation is present in TFPI-2: 85% in high-grade IPMNs and 17% in low-grade IPMNs[88]. Other genes are significantly more likely to be methylated in IPMNs with high-grade than in those with low-grade dysplasia: BNIP3 (57% in IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia, 20% in intermediate-grade dysplasia and 0% in low-grade dysplasia and in normal pancreas samples)[87], PTCHD2 (50% in high-grade dysplasia, 27% in intermediate-grade dysplasia, 0% in low-grade dysplasia and 6% in normal pancreas samples)[87], SOX17, NXPH1, EBF3[87], ppENK and p16[86].

Whereas in the IPMN-associated adenocarcinomas 55% of the samples is methylated at three or more gene promoters, in non-invasive IPMNs the hypermethylation involving three or more promoter regions is detectable in only 20% of the samples (all of these are associated with carcinoma in situ)[82].

Hence, the analysis of methylated DNA in pancreatic juice could be useful to differentiate, before surgery, invasive IPMNs from non-invasive IPMNs[86].

Moreover, since methylation at a specific genomic sites may predispose to tumor recurrence also after complete surgical extirpation, the methylation profile of the surgical resection margin in the absence of histological disease could be useful to identify a remnant pancreas at risk for tumor recurrence or for multifocal disease[86].

A significant difference in the percentage of genes methylated is also detectable between main-duct IPMNs and branch-duct IPMNs (71.3% ± 23.8% vs 44.4% ± 20%)[87,88].

The members of the S100 family are proteins containing a functional EF-hand calcium-binding domain[89]. They are localized in the cytoplasm and/or nucleus of many various cells and they are involved in Ca2+ signaling network, cell growth and motility, cell cycle progression, transcription and cell differentiation[90,91]. Sixteen S100 genes are described and they are located as a cluster on chromosome 1q21. Differently, the S100P gene is located at 4p16; it encodes the protein S100P (S100 calcium binding protein P), that, in addiction to binding Ca2+, also binds Zn2+ and Mg2+.The expression of this gene is increased in pancreatic cancer[92] and it is involved in its cell growth, survival and invasion[93]. In IPMNs, the levels of S100P in bulk pancreatic tissues are higher than in non-neoplastic pancreatic tissues; in microdissected cells, the levels of the protein are higher than in PDA and in PanIN cells, while, in pancreatic juice, IPMNs express higher levels of S100P than it was detected in chronic pancreatitis[94]. Then, S100P expression in pancreatic juice may be measured to discriminate neoplastic disease from chronic pancreatitis and S100P may be considered an early developmental marker of pancreatic carcinogenesis[94].

Protein S100 calcium binding protein A4 (S100A4), encoded by the S100A4 gene, is involved in the regulation of the motility and invasiveness of cancer cells and its altered expression is implicated in tumor metastasis[95]. The expression of S100A4 is increasing with the malignancy of IPMN: S100A4 protein is detectable in 7.4% of benign IPMNs (adenoma and borderline dysplasia) and in 42.9% of IPMN carcinomas. Thus, the expression of S100A4 could be a possible marker of malignancy, useful for the diagnosis and for providing the biological behavior of IPMN[23].

Protein S100 calcium binding protein A6 (S100A6), encoded by the S100A6 gene, is implicated in cell proliferation and invasion[96]. IPMN cells, as also PDA cells, express higher level of S100A6 than normal or pancreatitis-associated epithelial cells[96]. The alteration of S100A6 expression is an early event in pancreatic carcinogenesis; then, its expression gradually increases and so it may be considered a biomarker for the malignant potential. Measuring S100A6 in pancreatic juice may allow to detect early pancreatic cancer or to identify individuals with high-risk pancreatic lesions[96].

Protein S100 calcium binding protein A11 (S100A11), encoded by the S100A11 gene, plays an important role in the DNA damage response through a nucleolin-mediated translocation from the cytoplasm into the nucleus that correlates with an increased cellular p21 (the cell cycle regulator) protein level[97]. The levels of S100A11 in bulk tissues and in pancreatic juice are higher in PDA and in IPMN than in non-neoplastic samples, while, in microdissection analysis, IPMN cells are detected to express higher levels of S100A11 than PDA cells do[98]. This behavior suggests that S100A11 could be a tumor suppressor gene and its expression may decrease during progression from a benign to a malignant phenotype. The measurement of S100A11 expression in pancreatic juice may be useful for an early detection of pancreatic cancer, in particular for patients with high-risk lesions or chronic pancreatitis and patients with a family history of pancreatic cancer[98].

Correlation between mutation of the various genes and the different grades of dysplasia of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms is shown in Table 3.

| Ref. | Gene | Adenoma | Borderline | Carcinoma in situ | Invasive carcinoma |

| Wu et al[29], 2011 | KRAS2 | 87% | 90.2% | 70.7% | 70.7% |

| Dal Molin et al[36], 2013 | GNAS | 19% | 23% | 58% | 58% |

| Schönleben et al[41], 2006 | PI3KCA | 0% | 2.7% | 2.7% | 5.5% |

| Schönleben et al[22], 2007 | BRAF | 0% | 0% | 0% | 2.7% |

| Hashimoto et al[48], 2008 | hTERT | 15.8% | 35.7% | 85% | 86.7% |

| Jang et al[50], 2007 | Shh | 46.2% | 35.7% | 80% | 84.6% |

| Wada[26], 2002 | CDKN2A/p16 | 12.5% | 20% | 33% | 100% |

| Abe et al[64], 2007; Wada et al[26], 2002 | p53 | 0% | 33.3% | 38.5% | 100% |

| Biankin et al[55], 2002 | DPC4 | 0% | 0% | 38% | 75% |

| Dal Molin et al[81], 2012 | BRG1 | 28% | 52% | 76% | 76% |

| Jang et al[23], 2009 | S100A4 | 7.4% | 7.4% | 42.9% | 42.9% |

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small (18-24 nucleotides), single-stranded RNA molecules that regulate gene expression by binding messenger RNAs of genes at the 3’ untranslated region, resulting in degradation of the target messenger RNA or inhibition of translation[99]; so, the principal function of miRNAs is to regulate stability and translation of nuclear mRNA transcripts[100]. Their role in the control of proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis and their aberrant expression, leading to promotion of expression of proto-oncogenes or inhibition of tumor suppressor genes in many tumors, implies that they might function as tumor suppressor genes and as oncogenes[99,101-103].

Misexpression of miRNAs is commonly observed in pancreatic adenocarcinoma and its precursor lesions[99,104,105] and in IPMN[99].

The expression of the primary transcripts for miR-21 starts from chromosome 17q23.2; upregulation of miR-21 in cancer cells leads to apoptosis inhibition and acquisition of invasive properties[106]. Between the genes repressed by miR-21, there are the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), with the consequential activation of the Akt signaling pathway[107], and the PDC4, with the resulting promotion of cellular transformation and metastases[108].

miRNA-155 instead is co-expressed in conjunction with the non-coding transcript BIC, from chromosome 21q21.3[109]. Misexpression of miR-155 in pancreatic cancer represses the function of tumor protein 53 induced nuclear protein 1 (TP53INP1), that is pro-apoptotic[110].

miR-21 and miR-155 are significantly upregulated in the majority of non-invasive IPMNs and their expression correlates with histological features of progression[100].

miR-21 and miR-155 appear more up-regulated in invasive IPMNs compared with non-invasive IPMNs and with normal tissues[101], with a significantly greater proportion of IPMNs with carcinoma in situ expressing up-regulated miRNA compared to IPMN adenomas[100]. The percentage of miR-155 expression is 83% in IPMNs and 7% in normal ducts, whereas miR-21 expression reaches 81% in IPMNs and 2% in normal ducts[100]. Specifically, all the carcinoma in situ-IPMNs expressed miR-155, while it is expressed in 54% of IPMN adenomas, and 95% of IPMNs with carcinoma in situ expressed miR-21 while 54% of IPMN adenomas do it[100]. A significant higher proportion of carcinoma in situ-IPMNs expressed both miRNAs, compared to adenomas[100].

The association of the high levels of miR-21 with worse overall survival and a shorter median disease-free survival defines miR-21 as an independently prognostic factor for mortality and disease progression[101].

Differently from miR-155 and miR-21, expression of miR-101 is significantly higher in non-invasive IPMNs and normal tissues than in invasive IPMNs[101,111]. miR-101 could downregulate EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog-2, expression of which is significantly high in malignant IPMNs) in benign IPMNs, while a reduced level of miR-101 is attributable to increased expression of EZH2 in malignant IPMNs. Hence, low levels of miR-101 could be a trigger for the adenocarcinoma sequence of IPMN by upregulation of EZH2[111].

MUCs are a group of genes that transcribe for high molecular weight glycoproteins (mucins)[112]. Their function is the lubrication and the protection of epithelial mucosa, but they also play a role in homeostasis and carcinogenesis[113,114]. In the last years, core proteins for various human mucins have been identified (MUC1-9, MUC11-13, MUC15-20)[115-117]. Mucins are differentially expressed by several epithelial cells: goblet cells of the intestinal mucosa express overall MUC2 and then MUC3 and MUC4, that are expressed also by enterocytes. As regarding gastric mucosa, surface cells express MUC5AC and pyloric glands MUC6[118,119]. Ductal cells of the pancreas are principally characterized by the expression of MUC3, MUC5B and MUC6[120,121]. In pancreatic cancer, MUC1 and MUC2 are the more described and are respectively reported as markers of “aggressive” and “indolent” phenotypes[122,123].

MUC1 have an inhibitory role in cell-cell and cell-stroma interaction, mostly through integrins, and plays also a role in immunoresistance of neoplastic cells to cytotoxic T cells[124]. The MUC1 mucin mRNA is detected in several epithelial tissues and it is overexpressed in pancreas[125], where it is commonly expressed in PanIN-3 (61%)[126] and in ductal adenocarcinoma. Only rarely MUC1 is detectable in non-invasive, non-pancreatobiliary-type IPMN and colloid carcinoma[127]. In IPMNs, MUC1 expression has a specificity of 90% for the presence of tubular type invasion[126]. The expression of MUC1 in IPMNs is low, mainly in lower grade lesions; indeed, MUC1 expression is higher as the degree of dysplasia improves[126]. MUC1 expression is detectable in 8.6% of adenoma/borderline IPMNs and in 35.8% of carcinoma IPMNs[128]. High levels of MUC1 expression, its aberrant intracellular localization and changes in glycosylation are associated with an aggressive phenotype[127]. MUC1 overexpression is considered the most sensitive and specific marker of invasive carcinoma[129]. It is infrequent to detect MUC1 in cystic fluid of IPMNs[130].

MUC2 is a secretory mucin, associated with gel formation via polymers that are linked end to end by disulfide bonds and regulates cell proliferation via cysteine-rich domains[126]. It is expressed in the perinuclear region of the goblet cells of normal mucosa of the colon, small intestine and airways[112,131,132], providing an insoluble mucous barrier and protecting epithelium. It is never expressed in normal pancreatic tissue, but it is detectable in intestinal-type IPMN and colloid carcinoma[23,130]. MUC2 in cystic fluid is a marker of the intestinal subtype and delineates high-grade dysplasia/invasive cancer[127,133].

The expression of MUC2 rises from early IPMN (adenoma and borderline) to higher grade IPMN (carcinoma in situ) to colloid carcinoma (30%, 54% and 100%, respectively)[126], in contrast to ordinary ductal adenocarcinomas of the pancreas, where 63% are MUC1+ and only 1% is MUC2+[123,126,134].

In case of invasive carcinomas developing from IPMN, colloid carcinomas are exclusively MUC2+ (100%) and MUC1-, whereas 60% of tubular adenocarcinomas express MUC1 and only 1% of them expresses MUC2. In the IPMNs with MUC2+ expression, a carcinomatous component has been observed in the 89% of the cases, whereas, in case of MUC2- expression, it has been observed in only the 19% of the cases. Invasive carcinoma is more frequent in the IPMNs with MUC2+ expression (67%) than in the IPMNs with MUC2- expression (6%), so the clinical outcome for patients with IPMN with MUC2+ pattern tended to be worse than for those with IPMN with MUC2- pattern[112].

IPMNs with MUC2- pattern have low incidence of carcinoma in tumors under 4 cm in diameter, whereas IPMNs with MUC2+ pattern have a high incidence of carcinoma even in small tumors. Hence, the incidence of carcinoma in the MUC2- tumors is correlated with tumor size, while in the MUC2+ tumors there is no correlation with tumor size. In the light of this behavior, it is unlikely that MUC2+ tumors are derived from MUC2- tumors; so, the two types of tumors arise from different cell lineages[112].

MUC4 is a transmembrane ligand for ErbB-2, functioning in cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions[135]. Through alteration of cell properties and modulation of ErbB-2 expression, it acts on tumor growth and metastases[136]. MUC4 is not detectable in normal pancreatic tissue and it is expressed more frequently in high-grade and invasive IPMNs, with a worse overall survival in pancreatic cancer[136,137]. MUC4 is secreted into the cyst fluid and, in high-risk cysts, it is present in higher concentrations[127,136]. This increase in high-risk cysts could be reflective of activation of the ErbB-2 signaling pathway that may transform borderline cysts to a malignant phenotype[127,136]. Hence, MUC4 could be involved in the progression of adenoma cells to more aggressive cells and to be considered a diagnostic molecular marker indicating the existence of cellular atypia[136].

MUC5AC is a secretory mucin abundantly present in the stomach on the gastric mucosa[138]. Its aberrant expression is present in Barret esophagus[139], in gastric metaplasia in the duodenum[140] and in the colonic adenoma or cancer[131,138]. It seems to form a protective gel around tumors[141], that may be advantageous for all neoplasms. As MUC2, MUC5AC is never expressed in the normal pancreatic tissue, but is detectable in all types of IPMN and in PanINs[127,136]. The increase of expression of MUC5AC is an early event in pancreatic carcinogenesis[142]. MUC5AC is involved in the transition of hyperplastic cells to adenoma cells, so it could be a unique marker to differentiate IPMN tumor lesions from hyperplastic lesions, for its presence in all IPMN lesions, irrespective of histologic grades and epithelial subtypes[128,136].

The synchronous expression of MUC4 and MUC5AC in about half of adenoma IPMNs and almost all borderline and malignant IPMNs suggests that they act cooperatively to the carcinogenesis of IPMNs[136].

MUC6, a pyloric-type mucin, plays an important role in foregut differentiation of cells and it is implicated in gastric and pancreatic carcinogenesis[142]. Its expression is detectable in the intercalated ducts of the pancreas, in the small pancreatic tributary ducts with pyloric features and in Brunner glands of the duodenum, with focal granular labeling in some acini[134,143].

MUC6 seems to be regulated by key molecules such as Sp and NFκB, known for their important roles in pancreatic tumorigenesis[144,145].

The direction of differentiation in the various histological types of IPMNs is reflected in the expression of mucins: MUC1 is expressed in pancreatobiliary-type, MUC2 in intestinal-type, while MUC5AC is typically expressed in gastric-type IPMN. MUC5A can also be found, in combination with MUC1, in pancreatobiliary and oncocytic types or, in combination with MUC2, in the intestinal type IPMN[18,146]. As regarding MUC6, IPMNs characterized by oncocytic-type papillae show diffuse and strong MUC6 expression; IPMNs with pancreatobiliary-type papillae also consistently express MUC6, but the degree of expression is less intense than in oncocytic samples[143].

The feasibility of evaluating MUC expression from material obtained by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration has been assessed[147,148]; RNA can be extracted from biopsies obtained under endoscopic ultrasound with fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA). A relationship between the abnormal expression of some classes of MUCs and IPMNs has been demonstrated[147,148]; MUC7 could be a potential biological marker to identify malignant lesions[147] (Table 4).

| MUC1 | MUC2 | MUC5AC | MUC6 | |

| Gastric | - | - | + | - |

| Intestinal | - | + | + | - |

| Pancreatobiliary | + | - | + | + |

| Oncocytic | - | - | + | + |

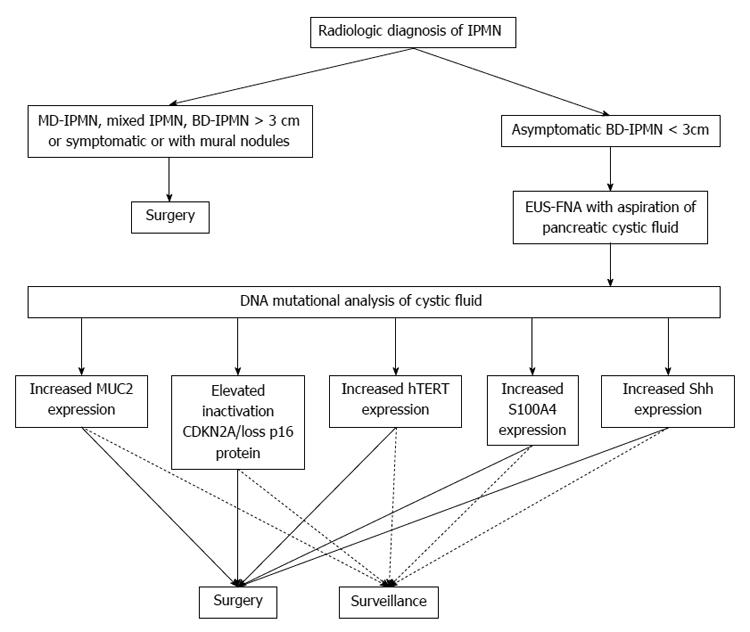

The data exposed so far must be applied to the clinical management of IPMNs in order to differentiate low-risk from high-risk lesions and to determinate which patients need surgery and which can be maintained under surveillance.

EUS-FNA of pancreatic cyst fluid sampling could be the procedure that enables to discriminate between benign and malignant IPMNs. The information we can obtain from cystic fluid analysis is various. Some authors proposed to measure the levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) concentration, but actually CEA is suitable only for the diagnosis of a mucinous cyst and not for the distinction of the degree of dysplasia[149,150].

More information instead can result from DNA analysis of pancreatic cystic fluid: DNA quantification, allelic imbalance/loss of heterozygosity and point mutations. The most significant markers in differentiating malignant IPMNs from benign IPMN lesions, among the genes presented in this paper, are MUC2, CDKN2A/p16, hTERT, S100A4 and Shh. In light of the percentage values of mutation in relation to the degree of dysplasia found in Literature, the analysis of DNA mutation detailed for these genes could be helpful to delineate IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia or invasive cancer that need surgical resection and adenoma and borderline IPMNs that can be maintained in follow-up.

In literature, KRAS is frequently reported as a possible indicator of malignancy in IPMNs; however, the lack of significant difference among the incidence of KRAS mutation in the various degrees of dysplasia makes KRAS inadequate in identifying benign and malignant IPMNs, being highly specific only for mucinous differentiation of pancreatic cysts[151] (Figure 1).

As stated above in this paper, the knowledge of molecular biology of IPMNs has impressively developed over the last few years, but more research is needed to use this information for clinical intent, in order to better define the natural history of these diseases. In addition, IPMN represent a very interesting histological and molecular model of pancreatic neoplasm, and, as it may be considered as precursor of PDA, new insights into the molecular pathology of this neoplasm could be of interest for the understanding of the biology of PDA.

P- Reviewer: Khalifa M, Mino-Kenudson M, Papavramidis TS, Toti L S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Ohashi K, Murakami Y, Murayama M, Takekoshi T, Ohta H, Ohashi I. Four cases of mucus secreting pancreatic cancer. Prog Dig Endosc. 1982;20:348-351. |

| 2. | Crippa S, Salvia R, Warshaw AL, Domínguez I, Bassi C, Falconi M, Thayer SP, Zamboni G, Lauwers GY, Mino-Kenudson M. Mucinous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas is not an aggressive entity: lessons from 163 resected patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247:571-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zamboni G, Scarpa A, Bogina G, Iacono C, Bassi C, Talamini G, Sessa F, Capella C, Solcia E, Rickaert F. Mucinous cystic tumors of the pancreas: clinicopathological features, prognosis, and relationship to other mucinous cystic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:410-422. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Longnecker DS, Kloppel G. Intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors. Pathology and Genetics of tumors of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC Press 2000; 237-241. |

| 5. | Fernández-del Castillo C, Targarona J, Thayer SP, Rattner DW, Brugge WR, Warshaw AL. Incidental pancreatic cysts: clinicopathologic characteristics and comparison with symptomatic patients. Arch Surg. 2003;138:427-423; discussion 433-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Crippa S, Fernández-Del Castillo C, Salvia R, Finkelstein D, Bassi C, Domínguez I, Muzikansky A, Thayer SP, Falconi M, Mino-Kenudson M. Mucin-producing neoplasms of the pancreas: an analysis of distinguishing clinical and epidemiologic characteristics. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:213-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Fernández-del Castillo C, Adsay NV. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:708-713, 713.e1-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kimura W, Nagai H, Kuroda A, Muto T, Esaki Y. Analysis of small cystic lesions of the pancreas. Int J Pancreatol. 1995;18:197-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 269] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tanaka M, Chari S, Adsay V, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Falconi M, Shimizu M, Yamaguchi K, Yamao K, Matsuno S. International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2006;6:17-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1539] [Cited by in RCA: 1441] [Article Influence: 75.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rodriguez JR, Salvia R, Crippa S, Warshaw AL, Bassi C, Falconi M, Thayer SP, Lauwers GY, Capelli P, Mino-Kenudson M. Branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: observations in 145 patients who underwent resection. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:72-79; quiz 309-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 352] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tanno S, Nakano Y, Nishikawa T, Nakamura K, Sasajima J, Minoguchi M, Mizukami Y, Yanagawa N, Fujii T, Obara T. Natural history of branch duct intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas without mural nodules: long-term follow-up results. Gut. 2008;57:339-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lévy P, Jouannaud V, O’Toole D, Couvelard A, Vullierme MP, Palazzo L, Aubert A, Ponsot P, Sauvanet A, Maire F. Natural history of intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas: actuarial risk of malignancy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:460-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hruban RH, Takaori K, Klimstra DS, Adsay NV, Albores-Saavedra J, Biankin AV, Biankin SA, Compton C, Fukushima N, Furukawa T. An illustrated consensus on the classification of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:977-987. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Bosman FTCF, Hruban RH, Theise ND. WHO classification of tumors of the digestive system. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC press 2010; . |

| 15. | Mino-Kenudson M, Fernández-del Castillo C, Baba Y, Valsangkar NP, Liss AS, Hsu M, Correa-Gallego C, Ingkakul T, Perez Johnston R, Turner BG. Prognosis of invasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm depends on histological and precursor epithelial subtypes. Gut. 2011;60:1712-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Caponi S, Vasile E, Funel N, De Lio N, Campani D, Ginocchi L, Lucchesi M, Caparello C, Lencioni M, Cappelli C. Adjuvant chemotherapy seems beneficial for invasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:396-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Swartz MJ, Hsu CC, Pawlik TM, Winter J, Hruban RH, Guler M, Schulick RD, Cameron JL, Laheru DA, Wolfgang CL. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy after pancreatic resection for invasive carcinoma associated with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:839-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Furukawa T, Klöppel G, Volkan Adsay N, Albores-Saavedra J, Fukushima N, Horii A, Hruban RH, Kato Y, Klimstra DS, Longnecker DS. Classification of types of intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: a consensus study. Virchows Arch. 2005;447:794-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 503] [Cited by in RCA: 474] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Adsay NV, Adair CF, Heffess CS, Klimstra DS. Intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasms of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:980-994. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Chari ST, Yadav D, Smyrk TC, DiMagno EP, Miller LJ, Raimondo M, Clain JE, Norton IA, Pearson RK, Petersen BT. Study of recurrence after surgical resection of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1500-1507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 401] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Salvia R, Partelli S, Crippa S, Landoni L, Capelli P, Manfredi R, Bassi C, Pederzoli P. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas with multifocal involvement of branch ducts. Am J Surg. 2009;198:709-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Schönleben F, Qiu W, Bruckman KC, Ciau NT, Li X, Lauerman MH, Frucht H, Chabot JA, Allendorf JD, Remotti HE. BRAF and KRAS gene mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm/carcinoma (IPMN/IPMC) of the pancreas. Cancer Lett. 2007;249:242-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jang JY, Park YC, Song YS, Lee SE, Hwang DW, Lim CS, Lee HE, Kim WH, Kim SW. Increased K-ras mutation and expression of S100A4 and MUC2 protein in the malignant intraductal papillary mucinous tumor of the pancreas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:668-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Z'graggen K, Rivera JA, Compton CC, Pins M, Werner J, Fernández-del Castillo C, Rattner DW, Lewandrowski KB, Rustgi AK, Warshaw AL. Prevalence of activating K-ras mutations in the evolutionary stages of neoplasia in intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 1997;226:491-498; discussion 498-500. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Sessa F, Solcia E, Capella C, Bonato M, Scarpa A, Zamboni G, Pellegata NS, Ranzani GN, Rickaert F, Klöppel G. Intraductal papillary-mucinous tumours represent a distinct group of pancreatic neoplasms: an investigation of tumour cell differentiation and K-ras, p53 and c-erbB-2 abnormalities in 26 patients. Virchows Arch. 1994;425:357-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wada K. p16 and p53 gene alterations and accumulations in the malignant evolution of intraductal papillary-mucinous tumors of the pancreas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:76-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Longnecker DS, Adsay NV, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Hruban RH, Kasugai T, Klimstra DS, Klöppel G, Lüttges J, Memoli VA, Tosteson TD. Histopathological diagnosis of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms: interobserver agreement. Pancreas. 2005;31:344-349. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Schönleben F, Qiu W, Remotti HE, Hohenberger W, Su GH. PIK3CA, KRAS, and BRAF mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm/carcinoma (IPMN/C) of the pancreas. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:289-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wu J, Matthaei H, Maitra A, Dal Molin M, Wood LD, Eshleman JR, Goggins M, Canto MI, Schulick RD, Edil BH. Recurrent GNAS mutations define an unexpected pathway for pancreatic cyst development. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:92ra66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 628] [Cited by in RCA: 595] [Article Influence: 42.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kitago M, Ueda M, Aiura K, Suzuki K, Hoshimoto S, Takahashi S, Mukai M, Kitajima M. Comparison of K-ras point mutation distributions in intraductal papillary-mucinous tumors and ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Int J Cancer. 2004;110:177-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yamaguchi K, Chijiiwa K, Torata N, Kinoshita M, Tanaka M. Telomerase activity, P53 mutation and Ki-ras codon 12 point mutation of the peripheral blood in patients with hepato pancreato biliary diseases. HPB (Oxford). 2002;4:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kondo H, Sugano K, Fukayama N, Hosokawa K, Ohkura H, Ohtsu A, Mukai K, Yoshida S. Detection of K-ras gene mutations at codon 12 in the pancreatic juice of patients with intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas. Cancer. 1997;79:900-905. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Uehara H, Nakaizumi A, Baba M, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Kitamura T, Ohigashi H, Ishikawa O, Takenaka A, Ishiguro S. Diagnosis of pancreatic cancer by K-ras point mutation and cytology of pancreatic juice. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1616-1621. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Kobayashi N, Inamori M, Fujita K, Fujisawa T, Fujisawa N, Takahashi H, Yoneda M, Abe Y, Kawamura H, Shimamura T. Characterization of K-ras gene mutations in association with mucinous hypersecretion in intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:169-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Furukawa T, Kuboki Y, Tanji E, Yoshida S, Hatori T, Yamamoto M, Shibata N, Shimizu K, Kamatani N, Shiratori K. Whole-exome sequencing uncovers frequent GNAS mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Sci Rep. 2011;1:161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 334] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Dal Molin M, Matthaei H, Wu J, Blackford A, Debeljak M, Rezaee N, Wolfgang CL, Butturini G, Salvia R, Bassi C. Clinicopathological correlates of activating GNAS mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) of the pancreas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:3802-3808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Katso R, Okkenhaug K, Ahmadi K, White S, Timms J, Waterfield MD. Cellular function of phosphoinositide 3-kinases: implications for development, homeostasis, and cancer. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:615-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 851] [Cited by in RCA: 953] [Article Influence: 41.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A, Silliman N, Ptak J, Szabo S, Yan H, Gazdar A, Powell SM, Riggins GJ. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304:554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2599] [Cited by in RCA: 2760] [Article Influence: 131.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Campbell IG, Russell SE, Choong DY, Montgomery KG, Ciavarella ML, Hooi CS, Cristiano BE, Pearson RB, Phillips WA. Mutation of the PIK3CA gene in ovarian and breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7678-7681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 689] [Cited by in RCA: 719] [Article Influence: 34.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Lee JW, Soung YH, Kim SY, Lee HW, Park WS, Nam SW, Kim SH, Lee JY, Yoo NJ, Lee SH. PIK3CA gene is frequently mutated in breast carcinomas and hepatocellular carcinomas. Oncogene. 2005;24:1477-1480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 418] [Cited by in RCA: 409] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Schönleben F, Qiu W, Ciau NT, Ho DJ, Li X, Allendorf JD, Remotti HE, Su GH. PIK3CA mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm/carcinoma of the pancreas. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3851-3855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Artandi SE, Chang S, Lee SL, Alson S, Gottlieb GJ, Chin L, DePinho RA. Telomere dysfunction promotes non-reciprocal translocations and epithelial cancers in mice. Nature. 2000;406:641-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 838] [Cited by in RCA: 807] [Article Influence: 32.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, Harley CB, West MD, Ho PL, Coviello GM, Wright WE, Weinrich SL, Shay JW. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science. 1994;266:2011-2015. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Maser RS, DePinho RA. Connecting chromosomes, crisis, and cancer. Science. 2002;297:565-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 416] [Cited by in RCA: 394] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | O'Hagan RC, Chang S, Maser RS, Mohan R, Artandi SE, Chin L, DePinho RA. Telomere dysfunction provokes regional amplification and deletion in cancer genomes. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:149-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Nakamura TM, Morin GB, Chapman KB, Weinrich SL, Andrews WH, Lingner J, Harley CB, Cech TR. Telomerase catalytic subunit homologs from fission yeast and human. Science. 1997;277:955-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1680] [Cited by in RCA: 1660] [Article Influence: 59.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Bodnar AG, Ouellette M, Frolkis M, Holt SE, Chiu CP, Morin GB, Harley CB, Shay JW, Lichtsteiner S, Wright WE. Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells. Science. 1998;279:349-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3573] [Cited by in RCA: 3444] [Article Influence: 127.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Hashimoto Y, Murakami Y, Uemura K, Hayashidani Y, Sudo T, Ohge H, Fukuda E, Shimamoto F, Sueda T, Hiyama E. Telomere shortening and telomerase expression during multistage carcinogenesis of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:17-28; discussion 28-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Parkin CA, Ingham PW. The adventures of Sonic Hedgehog in development and repair. I. Hedgehog signaling in gastrointestinal development and disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G363-G367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Jang KT, Lee KT, Lee JG, Choi SH, Heo JS, Choi DW, Ahn G. Immunohistochemical expression of Sonic hedgehog in intraductal papillary mucinous tumor of the pancreas. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2007;15:294-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Ohuchida K, Mizumoto K, Fujita H, Yamaguchi H, Konomi H, Nagai E, Yamaguchi K, Tsuneyoshi M, Tanaka M. Sonic hedgehog is an early developmental marker of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: clinical implications of mRNA levels in pancreatic juice. J Pathol. 2006;210:42-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Satoh K, Kanno A, Hamada S, Hirota M, Umino J, Masamune A, Egawa S, Motoi F, Unno M, Shimosegawa T. Expression of Sonic hedgehog signaling pathway correlates with the tumorigenesis of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Oncol Rep. 2008;19:1185-1190. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Maitra A, Hruban RH. Pancreatic cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:157-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 604] [Cited by in RCA: 589] [Article Influence: 34.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Delpu Y, Hanoun N, Lulka H, Sicard F, Selves J, Buscail L, Torrisani J, Cordelier P. Genetic and epigenetic alterations in pancreatic carcinogenesis. Curr Genomics. 2011;12:15-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Biankin AV, Biankin SA, Kench JG, Morey AL, Lee CS, Head DR, Eckstein RP, Hugh TB, Henshall SM, Sutherland RL. Aberrant p16(INK4A) and DPC4/Smad4 expression in intraductal papillary mucinous tumours of the pancreas is associated with invasive ductal adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2002;50:861-868. [PubMed] |

| 56. | Fujii H, Inagaki M, Kasai S, Miyokawa N, Tokusashi Y, Gabrielson E, Hruban RH. Genetic progression and heterogeneity in intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1447-1454. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Schneider G, Schmid RM. Genetic alterations in pancreatic carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2003;2:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Hong SM, Park JY, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Molecular signatures of pancreatic cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:716-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat Med. 2004;10:789-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2905] [Cited by in RCA: 2772] [Article Influence: 132.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Redston MS, Caldas C, Seymour AB, Hruban RH, da Costa L, Yeo CJ, Kern SE. p53 mutations in pancreatic carcinoma and evidence of common involvement of homocopolymer tracts in DNA microdeletions. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3025-3033. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Apple SK, Hecht JR, Lewin DN, Jahromi SA, Grody WW, Nieberg RK. Immunohistochemical evaluation of K-ras, p53, and HER-2/neu expression in hyperplastic, dysplastic, and carcinomatous lesions of the pancreas: evidence for multistep carcinogenesis. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:123-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Kaino M, Kondoh S, Okita S, Hatano S, Shiraishi K, Kaino S, Okita K. Detection of K-ras and p53 gene mutations in pancreatic juice for the diagnosis of intraductal papillary mucinous tumors. Pancreas. 1999;18:294-299. [PubMed] |

| 63. | Kitagawa Y, Unger TA, Taylor S, Kozarek RA, Traverso LW. Mucus is a predictor of better prognosis and survival in patients with intraductal papillary mucinous tumor of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:12-18; discussion 18-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Abe K, Suda K, Arakawa A, Yamasaki S, Sonoue H, Mitani K, Nobukawa B. Different patterns of p16INK4A and p53 protein expressions in intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms and pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Pancreas. 2007;34:85-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Miyasaka Y, Nagai E, Yamaguchi H, Fujii K, Inoue T, Ohuchida K, Yamada T, Mizumoto K, Tanaka M, Tsuneyoshi M. The role of the DNA damage checkpoint pathway in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4371-4377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Boland CR, Sato J, Appelman HD, Bresalier RS, Feinberg AP. Microallelotyping defines the sequence and tempo of allelic losses at tumour suppressor gene loci during colorectal cancer progression. Nat Med. 1995;1:902-909. [PubMed] |

| 67. | Hahn SA, Schutte M, Hoque AT, Moskaluk CA, da Costa LT, Rozenblum E, Weinstein CL, Fischer A, Yeo CJ, Hruban RH. DPC4, a candidate tumor suppressor gene at human chromosome 18q21.1. Science. 1996;271:350-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1723] [Cited by in RCA: 1669] [Article Influence: 57.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Wilentz RE, Argani P, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Kern SE, Hruban RH. Dpc4 protein in mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: frequent loss of expression in invasive carcinomas suggests a role in genetic progression. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1544-1548. [PubMed] |

| 69. | Moskaluk CA, Hruban RH, Schutte M, Lietman AS, Smyrk T, Fusaro L, Fusaro R, Lynch J, Yeo CJ, Jackson CE. Genomic sequencing of DPC4 in the analysis of familial pancreatic carcinoma. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1997;6:85-90. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Schutte M, Hruban RH, Hedrick L, Cho KR, Nadasdy GM, Weinstein CL, Bova GS, Isaacs WB, Cairns P, Nawroz H. DPC4 gene in various tumor types. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2527-2530. [PubMed] |

| 71. | Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Klimstra DS, Adsay NV, Wilentz RE, Argani P, Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Kern SE, Hruban RH. Dpc-4 protein is expressed in virtually all human intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: comparison with conventional ductal adenocarcinomas. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:755-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Blackford A, Serrano OK, Wolfgang CL, Parmigiani G, Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Eshleman JR. SMAD4 gene mutations are associated with poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4674-4679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 296] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Fu B, Yachida S, Luo M, Abe H, Henderson CM, Vilardell F, Wang Z, Keller JW, Banerjee P. DPC4 gene status of the primary carcinoma correlates with patterns of failure in patients with pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1806-1813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 770] [Cited by in RCA: 852] [Article Influence: 53.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Tiainen M, Ylikorkala A, Mäkelä TP. Growth suppression by Lkb1 is mediated by a G(1) cell cycle arrest. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9248-9251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Karuman P, Gozani O, Odze RD, Zhou XC, Zhu H, Shaw R, Brien TP, Bozzuto CD, Ooi D, Cantley LC. The Peutz-Jegher gene product LKB1 is a mediator of p53-dependent cell death. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1307-1319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Su GH, Hruban RH, Bansal RK, Bova GS, Tang DJ, Shekher MC, Westerman AM, Entius MM, Goggins M, Yeo CJ. Germline and somatic mutations of the STK11/LKB1 Peutz-Jeghers gene in pancreatic and biliary cancers. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1835-1840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Sato N, Rosty C, Jansen M, Fukushima N, Ueki T, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Hruban RH, Goggins M. STK11/LKB1 Peutz-Jeghers gene inactivation in intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:2017-2022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Zbuk KM, Eng C. Hamartomatous polyposis syndromes. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:492-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Giardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Tersmette AC, Goodman SN, Petersen GM, Booker SV, Cruz-Correa M, Offerhaus JA. Very high risk of cancer in familial Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1447-1453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 961] [Cited by in RCA: 868] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Shi C, Hruban RH. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:1-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Dal Molin M, Hong SM, Hebbar S, Sharma R, Scrimieri F, de Wilde RF, Mayo SC, Goggins M, Wolfgang CL, Schulick RD. Loss of expression of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling subunit BRG1/SMARCA4 is frequently observed in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:585-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | House MG, Guo M, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Herman JG. Molecular progression of promoter methylation in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) of the pancreas. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:193-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Fukushige S, Horii A. DNA methylation in cancer: a gene silencing mechanism and the clinical potential of its biomarkers. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2013;229:173-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Esteller M, Corn PG, Baylin SB, Herman JG. A gene hypermethylation profile of human cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3225-3229. [PubMed] |

| 85. | Baylin SB, Herman JG, Graff JR, Vertino PM, Issa JP. Alterations in DNA methylation: a fundamental aspect of neoplasia. Adv Cancer Res. 1998;72:141-196. [PubMed] |

| 86. | Sato N, Goggins M. Epigenetic alterations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:280-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Hong SM, Omura N, Vincent A, Li A, Knight S, Yu J, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Genome-wide CpG island profiling of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:700-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Sato N, Parker AR, Fukushima N, Miyagi Y, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Eshleman JR, Goggins M. Epigenetic inactivation of TFPI-2 as a common mechanism associated with growth and invasion of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2005;24:850-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Schäfer BW, Heizmann CW. The S100 family of EF-hand calcium-binding proteins: functions and pathology. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:134-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 513] [Cited by in RCA: 482] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Donato R. S100: a multigenic family of calcium-modulated proteins of the EF-hand type with intracellular and extracellular functional roles. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:637-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1140] [Cited by in RCA: 1184] [Article Influence: 49.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Leclerc E, Fritz G, Vetter SW, Heizmann CW. Binding of S100 proteins to RAGE: an update. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:993-1007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 329] [Cited by in RCA: 389] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Ashfaq R, Maitra A, Adsay NV, Shen-Ong GL, Berg K, Hollingsworth MA, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Kern SE. Highly expressed genes in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas: a comprehensive characterization and comparison of the transcription profiles obtained from three major technologies. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8614-8622. [PubMed] |

| 93. | Arumugam T, Simeone DM, Van Golen K, Logsdon CD. S100P promotes pancreatic cancer growth, survival, and invasion. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5356-5364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Ohuchida K, Mizumoto K, Egami T, Yamaguchi H, Fujii K, Konomi H, Nagai E, Yamaguchi K, Tsuneyoshi M, Tanaka M. S100P is an early developmental marker of pancreatic carcinogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5411-5416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Sekine H, Chen N, Sato K, Saiki Y, Yoshino Y, Umetsu Y, Jin G, Nagase H, Gu Z, Fukushige S. S100A4, frequently overexpressed in various human cancers, accelerates cell motility in pancreatic cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;429:214-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |