Published online Jun 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i23.7473

Revised: February 25, 2014

Accepted: April 15, 2014

Published online: June 21, 2014

Processing time: 199 Days and 17.7 Hours

AIM: To investigate the clinical features, response to corticosteroids, and prognosis of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH)-induced liver failure in China.

METHODS: A total of 22 patients (19 female and 3 male; average age 51 ± 15 years) with AIH-induced liver failure treated in our hospital from 2004 to 2012 were retrospectively analyzed. Clinical, biochemical and pathological characteristics of the 22 patients and responses to corticosteroid treatment in seven patients were examined retrospectively. The patients were divided into survivor and non-survivor groups, and the clinical characteristics and prognosis were compared between the two groups. The t test was used for data analysis of all categorical variables, and overall survival was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method.

RESULTS: At the time of diagnosis, mean IgG was 2473 ± 983 mg/dL, with three (18.8%) patients showing normal levels. All of the patients had elevated serum levels of antinuclear antibody (≥ 1:640). Liver histology from one patient showed diagnostic pathological changes, including massive necrosis and plasma cell infiltration. Four patients survived (18.2%) and 18 died (81.8%) without liver transplantation. The results showed that patients with low admission Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores (21.50 ± 2.08 vs 30.61 ± 6.70, P < 0.05) and corticosteroid therapy (100% vs 16.7%, P < 0.05) had better prognosis. A total of seven patients received corticosteroid therapy, of whom, four responded and survived, and the other three died. Survivors showed young age, shorter duration from diagnosis to corticosteroid therapy, low MELD score, and absence of hepatic encephalopathy at the time of corticosteroid administration. Six patients who were administered corticosteroids acquired fungal infections but recovered after antifungal therapy.

CONCLUSION: Early diagnosis and corticosteroid therapy are essential for improving the prognosis of patients with AIH-induced liver failure without liver transplantation.

Core tip: We describe the clinical characteristics and prognosis of autoimmune-hepatitis-induced liver failure in China. Early diagnosis and initiating corticosteroid therapy at an early stage may be essential for improving the prognosis of patients with AIH-induced liver failure without liver transplantation.

- Citation: Zhu B, You SL, Wan ZH, Liu HL, Rong YH, Zang H, Xin SJ. Clinical characteristics and corticosteroid therapy in patients with autoimmune-hepatitis-induced liver failure. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(23): 7473-7479

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i23/7473.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i23.7473

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a liver disease of unknown etiology that is characterized by chronic hepatic inflammation, presence of autoantibodies, and hypergammaglobulinemia[1]. AIH has protean manifestations that often affect young women, with the majority of patients presenting with subclinical or chronic disease. In many cases, cirrhosis is already established when diagnosis is made at the first presentation of symptoms. The disease may also occur acutely with jaundice in some patients; a subset of whom may develop acute and subacute liver failure[2,3].

Although there are a large number of AIH patients, only a few cases develop liver failure. In a survey in the United States carried out between 1998 and 2008, the major etiology of fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) in 1147 patients was acetaminophen overdose (46%), with only 5% of cases being induced by AIH[4]. Similar data were reported from Europe where 2%-5% of cases of FHF were induced by AIH[5,6] There were 19 (0.5%) patients with liver failure induced by AIH in our survey from 2002-2011, due to a high incidence of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection[7]. Although the incidence of AIH-induced liver failure is low, the prognosis of these patients remains poor, with a reported survival rate of only about 20% in those who do not undergo liver transplantation[7-9]. However, there are insufficient data for the clinical features and prognosis of AIH-induced liver failure in China.

Preferred treatment for patients with AIH is immunosuppression, including corticosteroids and azathioprine, and up to 70% of patients can achieve remission. Long-term treatment with azathioprine, with or without prednisolone, can prevent relapse[10,11]. However, the usefulness of immunosuppressive therapy in AIH-induced liver failure has not been well demonstrated. The management of corticosteroid therapy is controversial in these patients. Earlier studies have established the beneficial effects of corticosteroids in patients with acute severe (fulminant) AIH[12-14]. Responders to corticosteroids have been shown to have improvement or stabilization of bilirubin and International Normalized Ratio. In contrast, a survey from Ichai et al[15] reported that the initiation of corticosteroid therapy did not prevent liver transplantation in most patients, and empirical therapy in acute liver failure may delay or complicate liver transplantation. Moreover, the decision to initiate immunosuppressant drugs must be counterbalanced by the risk of septic complications[16]. Unfortunately, data on the use of corticosteroid therapy for patients with AIH-induced liver failure remain poorly described in China.

In this regard, the clinical features and prognosis of patients with AIH-induced liver failure were retrospectively analyzed in our hospital from 2004 to 2012. The management of corticosteroid therapy was also examined.

The retrospective study was carried out at the Liver Failure Treatment and Research Center of 302nd Military Hospital, Beijing, China between January 2004 and December 2012. A diagnosis of AIH was made based on the presence of anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) and/or anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA), and on the criteria defined by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG)[17,18]. A definite diagnosis required a pretreatment score > 15, while a probable diagnosis required a score between 10 and 15. The criteria for liver failure were used according to the Diagnostic and Treatment Guidelines of Liver Failure suggested by the Liver Failure and Artificial Liver Group, Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases of Chinese Medical Association[19]. Acute liver failure (ALF) was defined as the presence of coagulopathy [prothrombin activity (PTA) < 40%] and hepatic encephalopathy (grade 2) within 2 wk of the first symptoms without previous underlying liver disease. The patients with subacute liver failure had similar syndromes as acute liver failure (ALF) patients, but the duration of disease was 2-26 wk. Acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) was defined as acute liver decompensation on the basis of chronic liver disease with mandatory jaundice [total bilirubin (TBil) > 171.0 μmol/L or a rapid rise > 17.1 μmol/L per day], coagulopathy (PTA < 40%), and recent development of complications.

For all patients, there was no evidence of concurrent HBV, hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus, hepatitis E virus, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and no evidence of drug-induced, alcoholic liver disease or Wilson’s disease. Other conditions that can lead to liver failure were excluded in this study. All of the patients were followed up until 24 wk or death. A total of 22 patients (19 female and 3 male; average age 51.1 ± 14.5 years) were enrolled in this study.

The protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of 302 Military Hospital. All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before entering the study protocol.

Before corticosteroid therapy was initiated, an absence of sepsis was confirmed by negative cultures of blood samples, ascites fluids, and urine specimens, and by chest X-ray.

History of alcohol consumption, drug intake, blood transfusion, and medication in all patients was carefully reviewed. Serum autoantibodies, including ANA, ASMA, liver kidney microsomal antibody (LKM)-1 and antimitochondrial antibody (AMA), were tested using indirect immunofluorescence with the standard methods (EUROIMMUN, Germany), with a dilution of ≥ 1:100 considered as positive. Immunoglobulin assay was performed with the method of immunological turbidimetry (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany). The standard biochemical tests for the assessment of liver diseases, including alanine transaminase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), serum creatinine, plasma PTA, and TBil were routinely performed in the Central Clinical Laboratory of the 302nd Military Hospital. Liver biopsy was performed in one case for definite diagnosis, and the biopsy specimen was examined in the Pathology Department of the 302nd Military Hospital.

The results were expressed as mean ± SD. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t test. Categorical data were compared using Fisher’s exact test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data processing was carried out with SPSS for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

The clinical features of the 22 patients at the time of diagnosis are shown in Table 1. Thirteen (59.1%) of the patients had ACLF, one (4.5%) had ALF, and eight (36.4%) had subacute liver failure. All of the patients with ACLF had liver cirrhosis. At admission, nine (41%) patients suffered from hepatic encephalopathy. Four patients had systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Laboratory data at admission reflected severe hepatic dysfunction, with mean TBil of 22.5 ± 6.5 mg/dL, ALT of 317 ± 236 IU/L, and PTA of 29% ± 8%. The average serum creatinine level was 1.13 ± 0.54 mg/dL.

| Case | Age/sex (yr) | TBil (mg/dL) | PTA | ALT (IU/L) | ALP (IU/L) | Creatinine (mg/dL) | MELD | Liver cirrhosis | HE | SIRS | Liver failure type |

| 1 | 36/F | 13.9 | 28% | 300 | 185 | 0.77 | 22 | Yes | No | No | ACLF |

| 2 | 50/F | 10.1 | 27% | 326 | 107 | 0.63 | 29 | Yes | No | No | ACLF |

| 3 | 66/F | 21.3 | 12% | 452 | 275 | 0.77 | 30 | Yes | No | Yes | ACLF |

| 4 | 48/F | 26.6 | 38% | 374 | 158 | 1.37 | 27 | Yes | No | No | ACLF |

| 5 | 44/F | 21.7 | 32% | 280 | 134 | 0.83 | 32 | No | Yes | No | Subacute |

| 6 | 42/M | 32.8 | 39% | 791 | 144 | 1.32 | 31 | No | Yes | Yes | Subacute |

| 7 | 33/F | 29.0 | 30% | 139 | 148 | 0.93 | 24 | No | No | No | Subacute |

| 8 | 19/F | 15.6 | 33% | 234 | 439 | 2.87 | 36 | Yes | No | Yes | ACLF |

| 9 | 67/M | 25.5 | 19% | 145 | 54 | 0.87 | 29 | Yes | Yes | No | ACLF |

| 10 | 58/F | 27.9 | 36% | 274 | 212 | 1.23 | 30 | No | Yes | No | Subacute |

| 11 | 59/F | 24.0 | 20% | 138 | 150 | 1.50 | 41 | Yes | No | No | ACLF |

| 12 | 75/F | 19.6 | 30% | 725 | 173 | 0.86 | 23 | Yes | No | No | ACLF |

| 13 | 56/F | 29.8 | 31% | 268 | 420 | 0.80 | 31 | No | Yes | No | Subacute |

| 14 | 41/F | 32.5 | 5% | 99 | 81 | 1.87 | 44 | Yes | Yes | No | ACLF |

| 15 | 72/M | 27.4 | 19% | 400 | 195 | 1.54 | 38 | No | Yes | No | Acute |

| 16 | 45/F | 11.1 | 39% | 512 | 162 | 0.58 | 22 | Yes | No | No | ACLF |

| 17 | 45/F | 19.0 | 38% | 557 | 290 | 0.87 | 22 | No | No | No | Subacute |

| 18 | 39/F | 23.0 | 26% | 147 | 35 | 0.75 | 21 | Yes | Yes | No | ACLF |

| 19 | 72/F | 23.3 | 23% | 337 | 123 | 1.41 | 36 | Yes | Yes | No | ACLF |

| 20 | 52/F | 17.1 | 38% | 197 | 168 | 0.76 | 19 | No | No | No | Subacute |

| 21 | 65/F | 17.7 | 35% | 134 | 32 | 0.66 | 19 | No | No | Yes | Subacute |

| 22 | 40/F | 27.1 | 31% | 76 | 92 | 1.67 | 31 | Yes | No | No | ACLF |

All of the patients underwent ultrasound (US) examination, and 16 had computed tomography (CT). Both hepatic necrosis and liver regeneration were present in those patients who showed hypoattenuation and hyperattenuation areas on US and/or CT scans. Thirteen patients showed characteristics of liver cirrhosis, including echo coarseness, liver surface nodularity, and splenomegaly.

The immunoserological features of patients are shown in Table 2. All of the patients had positive ANA (≥ 1:100): > 1:1000 in 16 (72.7%), 1:640 in six (27.3%). AMSA was positive (≥ 1:100) in six (27.3%) patients. Two patients were positive for LKM-1. A total of 16 patients underwent immunoglobulin G (IgG) assay. The average serum level of IgG was 2473 ± 983 mg/dL, which was about 1.5-fold higher than normal (1660 mg/dL). The IgG level was normal in three (18.8%) patients. Percentage of γ-globulins was available in cases 3, 5, 8, 9 and 17 enrolled before 2008.

| Case | ANA (fold) | ASMA (fold) | LKM-1 (fold) | AMA | IgG (mg/dL) | AIH score | Simplified AIH score | Corticosteroid therapy | Outcome | Weeks from onset to death |

| 1 | > 1000 | - | - | - | 2807 | 17 | 6 | Yes | Survival | / |

| 2 | 640 | - | - | - | 5140 | 16 | 6 | No | Death | 11 |

| 3 | > 1000 | - | UD | - | 36% | 15 | 6 | No | Death | 10 |

| 4 | > 1000 | - | UD | - | 1140 | 13 | 4 | No | Death | 11 |

| 5 | 640 | - | - | - | 20% | 13 | 4 | No | Death | 3 |

| 6 | 640 | 80 | 320 | - | 1300 | 11 | 6 | No | Death | 6 |

| 7 | 640 | - | - | - | 2118 | 15 | 6 | Yes | Survival | / |

| 8 | > 1000 | 160 | - | - | 54% | 15 | 6 | No | Death | 5 |

| 9 | > 1000 | - | - | - | 30% | 12 | 6 | No | Death | 5 |

| 10 | > 1000 | 1000 | UD | - | 2026 | 14 | 6 | No | Death | 8 |

| 11 | > 1000 | - | - | - | 2358 | 14 | 6 | No | Death | 3 |

| 12 | > 1000 | - | UD | - | 1983 | 14 | 6 | Yes | Death | 22 |

| 13 | > 1000 | - | - | - | 3014 | 15 | 6 | No | Death | 2 |

| 14 | > 1000 | 320 | - | - | 2167 | 14 | 6 | No | Death | 3 |

| 15 | > 1000 | - | UD | - | UD | 12 | 4 | No | Death | 2 |

| 16 | > 1000 | 160 | UD | - | 2823 | 15 | 4 | Yes | Death | 19 |

| 17 | > 1000 | - | - | - | 23% | 13 | 5 | No | Death | 6 |

| 18 | > 1000 | - | - | - | 3553 | 18 | 6 | Yes | Survival | / |

| 19 | > 1000 | 1000 | - | - | 3474 | 19 | 8 | Yes | Death | 11 |

| 20 | 640 | - | 160 | - | 1456 | 14 | 6 | Yes | Survival | / |

| 21 | 640 | - | - | - | 1768 | 14 | 6 | No | Death | 12 |

| 22 | 1000 | - | - | - | 2776 | 15 | 6 | No | Death | 8 |

The AIH scoring system proposed by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group[17] was used to score all patients. The AIH score ranged from 11 to 19 (14.5 ± 1.9) before treatment. Four (18.2%) patients were diagnosed with definite AIH and 18 (81.8%) with probable AIH. Seven patients (31.8%) were administered corticosteroid therapy.

The outcomes of patients were evaluated at 24 wk. Four (18.2%) patients survived, and 18 (81.8%) died without liver transplantation. The average time from onset to death was 8.2 ± 5.6 wk (Table 2). Possible factors associated with survivors and non-survivors are shown in Table 3. The survivors were younger than non-survivors (40.0 ± 8.37 years vs 53.56 ± 14.58 years, P = 0.041). The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was 21.50 ± 2.08 and 30.61 ± 6.70 in survivors and non-survivors, respectively (P = 0.015), suggesting that non-survivors had a higher disease severity at the time of diagnosis. Comparison between survivors and non-survivors showed that corticosteroid treatment significantly improved survival rate (P = 0.002). However, there were no significant differences between survivors and non-survivors in biochemical parameters, ANA titer, IgG level, plasma exchange, and complications at the time of diagnosis. It should be mentioned that in non-survivors, eight patients had hepatic encephalopathy at the time of diagnosis and 10 had hepatic encephalopathy during the 24-wk follow-up. In survivors, only one patient had hepatic encephalopathy at the time of diagnosis of liver failure, with no increase during follow-up.

| Variables | Survivor (n = 4) | Non-survivor (n = 18) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 40.00 ± 8.37 | 53.56 ± 14.58 | 0.0411 |

| SIRS (yes), n (%) | 0 (0) | 4 (22.2) | - |

| Cirrhosis (yes), n (%) | 2 (50) | 11 (61) | 0.6852 |

| Acute/subacute/ACLF | 0/2/2 | 1/6/11 | - |

| TBil (mg/dL) | 20.75 ± 6.67 | 22.94 ± 6.58 | 0.4961 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 195.75 ± 74.09 | 340.11 ± 205.69 | 0.2681 |

| PTA (%) | 30 .50 ± 5.26 | 28.17 ± 9.87 | 0.9961 |

| MELD score | 21.50 ± 2.08 | 30.61 ± 6.70 | 0.0151 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy (yes), n (%) | 1 (25) | 8 (44) | 0.4632 |

| Ascites (yes), n (%) | 2 (50) | 14 (78) | 0.2802 |

| ANA (> 1:100) | 4 (100) | 18 (100) | - |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 2483.50 ± 901.45 | 2344.88 ± 1119.46 | 0.5911 |

| Corticosteroid treatment | 4 (100) | 3 (16.7) | 0.0012 |

| Plasma exchange, n (%) | 1 (25) | 3 (16.7) | 1.0002 |

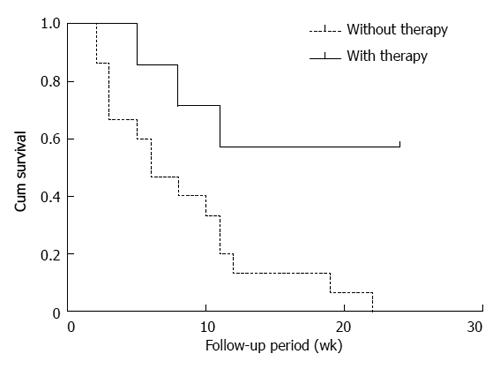

Seven patients were administered an initial dose of 20-50 mg/d prednisolone or methylprednisolone (Table 4). In order to improve treatment efficiency, azathioprine was added in cases 1, 12 and 16. Other patients were not treated due to hemocytopenia. The survival curve of the relationship with corticosteroid therapy is shown in Figure 1. The median survival time was significantly increased in patients with corticosteroid therapy compared with those who were not treated (P = 0.007). The survival rates were 57.1% and 0% in patients with or without corticosteroid therapy, respectively (P = 0.0218), suggesting that patients with corticosteroid therapy had better prognosis.

| Case | Treatment | Loading dose of corticosteroid (mg/d) | Duration (d)1 | MELD2 | Hepatic encephalopathy2 | Creatinine (mg/dL)2 | Adverse events | Outcome |

| 1 | mPSL | 30 | 16 | 23 | None | 0.77 | None | Survival |

| 7 | PSL | 50 | 26 | 24 | None | 0.93 | Oral fungal infection | Survival |

| 18 | mPSL | 32 | 35 | 19 | None | 0.75 | Oral fungal infection | Survival |

| 20 | mPSL | 32 | 21 | 20 | None | 0.76 | Oral fungal infection, pulmonary fungal infection | Survival |

| 12 | mPSL | 24 | 105 | 25 | None | 0.86 | Oral fungal infection, pulmonary fungal infection | Death |

| 16 | mPSL | 24 | 101 | 26 | None | 0.58 | Oral fungal infection | Death |

| 19 | PSL | 30 | 67 | 36 | Yes | 1.41 | Oral fungal infection | Death |

The clinical characteristics and outcomes of the seven patients who received corticosteroid therapy are summarized in Table 4. All of the patients were female. Four (57.1%) patients survived and three (42.9%) died without liver transplantation. The mean age was 41 years (range, 33-52 years) and 64 years (range, 45-72 years) in the survivors and non-survivors, respectively. The median period from diagnosis to corticosteroid application was 26 d (range, 16-35 d) and 91 d (range, 67-105 d) in survivors and non-survivors, respectively. The average MELD score before corticosteroid treatment was 21 and 29 in survivors and non-survivors, respectively. Infection occurred in six patients during corticosteroid therapy, including oral and pulmonary fungal infection. The patients recovered after newly developed antifungal therapy (caspofungin and voriconazole).

Only one patient underwent liver biopsy. Diagnostic pathological changes, including interface hepatitis, massive necrosis, and plasma cell infiltration were observed in that patient.

There is a paucity of published data on patients with AIH-induced liver failure; consisting mostly of small case series[13,15,20]. Thus, the clinical characteristics, response to immunosuppressants, and outcomes without liver transplantation of this cohort remain poorly described. Unfortunately, the previous criteria[17,18] were designed to differentiate AIH from other causes of chronic liver disease, rather than to address diagnostic considerations of ALF. Recently, clinical and histological criteria for autoimmune ALF have been suggested by groups in the US and Japan[21,22]. In our study, the patients who met the IAIHG criteria for AIH and the criteria for liver failure were diagnosed with AIH-induced liver failure.

The prevalence of AIH-induced liver failure differs according to geographical location. From 2004 to 2012, 22 patients were diagnosed with AIH-induced liver failure in our hospital. The 22 patients only accounted for 0.6% of liver failure in our survey. The incidence was significantly lower than that reported before[6,23], due to a high incidence of chronic HBV infection and cryptogenic liver failure[7]. Our previous study showed that AIH comprised 5.3% of patients with cryptogenic liver diseases[24]. The American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) suggests performing liver biopsy when AIH is suspected as the cause of ALF and autoantibodies are negative[25]. However, liver biopsy may be difficult or impossible for patients with liver failure because of the severity of the hepatic insult. Thus, it is likely that the cases of AIH-induced liver failure were confused with those of unknown etiology.

Our study showed that, similar to other studies[9,14], AIH-induced liver failure was more common in female patients, with a female:male ratio of roughly 6: 1. Serum autoantibodies have been established as biomarkers for the diagnosis of AIH. In our study, all patients had a high titer of serum ANA. IgG was the predominant immunoglobulin that was elevated in the serum of AIH patients. Thirteen of 16 patients had elevated levels of IgG, with an average of 2473 ± 983 mg/dL, which was about 1.5-fold higher than the normal serum level. A previous study has reported that immunoparesis is commonly seen in patients with liver failure in whom both autoantibodies and/or elevated IgG concentrations may be absent[26]. However, elevated serum levels of ANA and/or IgG were still critical markers for diagnosis of AIH-induced liver failure when liver biopsy was not performed in our study.

The outcome of liver failure induced by AIH is poor. In a recent series of 12 patients with fulminant forms of AIH reported by Fujiwara et al[9], two (17%) survived without liver transplantation, one (8%) survived with liver transplantation, and eight (67%) died without liver transplantation. In a Japanese nationwide survey between 1998 and 2003, the survival rate of patients with fulminant hepatitis and late-onset hepatic failure without liver transplantation was 17.1% in AIH[27]. In accordance with previous studies, the survival rate was 18.2% (4/22) in patients without liver transplantation in our study. The results also showed that patients with low admission MELD scores and corticosteroid therapy had better prognosis.

Whether corticosteroids increase the risk of septic complications in patients with severe liver disease is subject to an ongoing debate because liver failure itself is associated with an increased risk of bacterial and fungal infections[28]. In the study of Ichai et al[15], 42.3% of patients developed a septic event. In our study, among seven patients who received corticosteroid therapy, six developed fungal infections: of which, there was oral fungal infection in six and pulmonary fungal infection in two patients. These patients with fungal infections recovered because of early diagnosis using serum (1, 3)-β-D-glucan determination and use of newly developed antifungal agents, such as caspofungin and voriconazole[29,30]. Fungal infections seemed not to be related to prognosis in our study. Therefore, it is necessary to determine potential infections in the context of corticosteroid therapy and initiation of effective antifungal therapy as soon as possible.

In conclusion, patients with AIH-induced liver failure comprise a small proportion of those with liver failure in China. We should be aware of the possibility that cryptogenic liver failure is induced by AIH. The outcomes of patients with AIH-induced liver failure without liver transplantation are poor. Their prognosis might be improved by the introduction of sufficient immunosuppressive therapy either at an early stage or in patients with less disease severity. Multicenter studies with a large number of patients are also needed to clarify the clinical features of AIH-induced liver failure and define the treatment strategies.

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a liver disease of unknown etiology that often affects young women. The majority of patients present with subclinical or chronic disease. However, a subset of patients may develop acute and subacute liver failure. Although the incidence of AIH-induced liver failure is low, the prognosis of these patients remains poor in the absence of liver transplantation.

The use of corticosteroid therapy is controversial. To date, there are insufficient data regarding the clinical features, response to corticosteroids, and prognosis of AIH-induced liver failure in China.

The authors described the clinical characteristics and prognosis of AIH-induced liver failure in China. Twenty-two patients with AIH-induced liver failure from 2004 to 2012 were enrolled. The results showed that AIH-induced liver failure is a life-threatening liver disease with a survival rate of 18% without liver transplantation. Seven patients received corticosteroid therapy, of whom, four responded and survived and three died. Survivors showed young age, shorter duration from diagnosis to corticosteroid therapy, low Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score, and absence of hepatic encephalopathy at the time of corticosteroid administration.

The results suggest that early diagnosis and initiation of corticosteroid therapy at an early stage may be essential for improving the prognosis of patients with AIH-induced liver failure without liver transplantation.

A diagnosis of AIH-induced liver failure was based on the presence of antinuclear antibody and/or anti-smooth muscle antibody, and the criteria defined by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. The criteria for liver failure were those of the Diagnostic and Treatment Guidelines of Liver Failure suggested by the Liver Failure and Artificial Liver Group, Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases of Chinese Medical Association.

This was a good descriptive study with the strengths of a large sample assessed over a long period of time. It is the first study of the field done in China. The conclusions drawn from the analysis are reasonable and well considered.

P- Reviewers: Aggarwal A, Juergens KU S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Logan S E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Czaja AJ, Freese DK. Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2002;36:479-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 414] [Cited by in RCA: 389] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kessler WR, Cummings OW, Eckert G, Chalasani N, Lumeng L, Kwo PY. Fulminant hepatic failure as the initial presentation of acute autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:625-631. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Miyake Y, Iwasaki Y, Terada R, Onishi T, Okamoto R, Sakai N, Sakaguchi K, Shiratori Y. Clinical characteristics of fulminant-type autoimmune hepatitis: an analysis of eleven cases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1347-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee WM, Squires RH, Nyberg SL, Doo E, Hoofnagle JH. Acute liver failure: Summary of a workshop. Hepatology. 2008;47:1401-1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 566] [Cited by in RCA: 513] [Article Influence: 30.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Escorsell A, Mas A, de la Mata M. Acute liver failure in Spain: analysis of 267 cases. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1389-1395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Brandsaeter B, Höckerstedt K, Friman S, Ericzon BG, Kirkegaard P, Isoniemi H, Olausson M, Broome U, Schmidt L, Foss A. Fulminant hepatic failure: outcome after listing for highly urgent liver transplantation-12 years experience in the nordic countries. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:1055-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | You S, Rong Y, Zhu B, Zhang A, Zang H, Liu H, Li D, Wan Z, Xin S. Changing etiology of liver failure in 3,916 patients from northern China: a 10-year survey. Hepa Inter. 2013;7: 714-720. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiødt FV, Larson A, Davern TJ, Han SH, McCashland TM, Shakil AO, Hay JE, Hynan L. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:947-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1562] [Cited by in RCA: 1458] [Article Influence: 63.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fujiwara K, Yasui S, Tawada A, Okitsu K, Yonemitsu Y, Chiba T, Arai M, Kanda T, Imazeki F, Nakano M. Autoimmune fulminant liver failure in adults: Experience in a Japanese center. Hepatol Res. 2011;41:133-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Krawitt EL. Autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:897-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG, Williams R. Azathioprine for long-term maintenance of remission in autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:958-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sugawara K, Nakayama N, Mochida S. Acute liver failure in Japan: definition, classification, and prediction of the outcome. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:849-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Takikawa Y, Suzuki K. Clinical epidemiology of fulminant hepatitis in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2008;38 Suppl 1:S14-S18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yasui S, Fujiwara K, Yonemitsu Y, Oda S, Nakano M, Yokosuka O. Clinicopathological features of severe and fulminant forms of autoimmune hepatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:378-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ichai P, Duclos-Vallée JC, Guettier C, Hamida SB, Antonini T, Delvart V, Saliba F, Azoulay D, Castaing D, Samuel D. Usefulness of corticosteroids for the treatment of severe and fulminant forms of autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:996-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Crean JM, Niederman MS, Fein AM, Feinsilver SH. Rapidly progressive respiratory failure due to Aspergillus pneumonia: a complication of short-term corticosteroid therapy. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:148-150. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, Chapman RW, Cooksley WG, Czaja AJ, Desmet VJ. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929-938. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Parés A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, Bittencourt PL, Porta G, Boberg KM, Hofer H. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1205] [Cited by in RCA: 1251] [Article Influence: 73.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liver Failure and Artificial Liver Group, Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association; Severe Liver Diseases and Artificial Liver Group, Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association. [Diagnostic and treatment guidelines for liver failure]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Zazhi. 2006;14:643-646. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Herzog D, Rasquin-Weber AM, Debray D, Alvarez F. Subfulminant hepatic failure in autoimmune hepatitis type 1: an unusual form of presentation. J Hepatol. 1997;27:578-582. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Onji M. Proposal of autoimmune hepatitis presenting with acute hepatitis, severe hepatitis and acute liver failure. Hepatol Res. 2011;41:497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Stravitz RT, Lefkowitch JH, Fontana RJ, Gershwin ME, Leung PS, Sterling RK, Manns MP, Norman GL, Lee WM. Autoimmune acute liver failure: proposed clinical and histological criteria. Hepatology. 2011;53:517-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Verma S, Torbenson M, Thuluvath PJ. The impact of ethnicity on the natural history of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2007;46:1828-1835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rong YH, You SL, Liu HL, Zhu B, Zang H, Zhao JM, Li BS, Xin SJ. [Clinical and pathological analysis of 566 patients with cryptogenic liver diseases]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Zazhi. 2012;20:300-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Polson J, Lee WM. AASLD position paper: the management of acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2005;41:1179-1197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 644] [Cited by in RCA: 641] [Article Influence: 32.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gregorio GV, Portmann B, Reid F, Donaldson PT, Doherty DG, McCartney M, Mowat AP, Vergani D, Mieli-Vergani G. Autoimmune hepatitis in childhood: a 20-year experience. Hepatology. 1997;25:541-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 469] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Fujiwara K, Mochida S, Matsui A, Nakayama N, Nagoshi S, Toda G. Fulminant hepatitis and late onset hepatic failure in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2008;38:646-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Karvellas CJ, Pink F, McPhail M, Cross T, Auzinger G, Bernal W, Sizer E, Kutsogiannis DJ, Eltringham I, Wendon JA. Predictors of bacteraemia and mortality in patients with acute liver failure. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1390-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Maertens J, Boogaerts M. Caspofungin in the treatment of candidosis and aspergillosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2003;7:94-101. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Myrianthefs P, Markantonis SL, Evaggelopoulou P, Despotelis S, Evodia E, Panidis D, Baltopoulos G. Monitoring plasma voriconazole levels following intravenous administration in critically ill patients: an observational study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;35:468-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |