Published online May 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5548

Revised: March 2, 2014

Accepted: March 12, 2014

Published online: May 14, 2014

Processing time: 215 Days and 20.4 Hours

AIM: To compare the efficacy and safety of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation (EPLBD) with endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) in retrieval of common bile duct stones (≥ 10 mm).

METHODS: PubMed, Web of Knowledge, EBSCO, the Cochrane Library, and EMBASE were searched for eligible studies. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared EPLBD with EST were identified. Data extraction and quality assessment were performed by two independent reviewers using the same criteria. Any disagreement was discussed with a third reviewer until a final consensus was reached. Pooled outcomes of complete bile duct stone clearance, stone clearance in one session, requirement for mechanical lithotripsy, and overall complication rate were determined using relative risk and 95%CI. The separate post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography complications were pooled and determined with the Peto odds ratio and 95%CI because of the small number of events. Heterogeneity was evaluated with the chi-squared test with P≤ 0.1 and I2 with a cutoff of ≥ 50%. A fixed effects model was used primarily. A random effects model was applied when significant heterogeneity was detected. Sensitivity analysis was applied to explore the potential bias.

RESULTS: Five randomized controlled trials with 621 participants were included. EPLBD compared with EST had similar outcomes with regard to complete stone removal rate (93.7% vs 92.5%, P = 0.54) and complete duct clearance in one session (82.2% vs 77.7%, P = 0.17). Mechanical lithotripsy was performed less in EPLBD in the retrieval of whole stones (15.5% vs 25.2%, P = 0.003), as well as in the stratified subgroup of stones larger than 15 mm (24.2% vs 40%, P = 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of overall adverse events (7.9% vs 10.7%, P = 0.25), post-ERCP pancreatitis (4.0% vs 5.0%, P = 0.54), hemorrhage (1.7% vs 2.8%, P = 0.32), perforation (0.3% vs 0.9%, P = 0.35) or acute cholangitis (1.3% vs 1.3%, P = 0.92).

CONCLUSION: EPLBD could be advocated as an alternative to EST in the retrieval of large common bile duct stones.

Core tip: Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation (EPLBD) was as effective as endoscopic sphincterotomy in large common bile duct stone clearance. However, it had less requirement for endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy, even in stones larger than 15 mm. Besides, EPLBD could be conducted with limited or without precutting of the papilla which may be promising for application in patients with coagulopathy or with surgically modified anatomy. Further investigations are required to confirm this claim.

-

Citation: Jin PP, Cheng JF, Liu D, Mei M, Xu ZQ, Sun LM. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation

vs endoscopic sphincterotomy for retrieval of common bile duct stones: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(18): 5548-5556 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i18/5548.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5548

Per-oral endoscopy has been widely accepted as the first-line treatment in removal of common bile duct (CBD) stones, and has gradually replaced conventional surgery. Endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), as the most commonly used technique, was first introduced in 1974[1]. It involved a maximal papillotomy, which not only accounted for 8%-12% of acute adverse events like hemorrhage, perforation[2], but also for long term adverse events like sphincter dysfunction. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation, introduced as an alternative to EST by Staritz et al[3], could lower the risk of bleeding and perforation, but might result in higher risk of post-procedure pancreatitis[4-6]. Furthermore, it could only be applied in removing small to moderate sized stones (≤ 10 mm)[6]. Approximately 10%-15% of stones could not be removed by either of the above-mentioned techniques, most of which occurred with stones larger than 10-15 mm[7]. In addition, difficult stones (larger than 15 mm, and multiple, barrel-shaped and impacted stones), challenging access to papilla (periampullary diverticulum or postoperative variation), and tortuosity and tapering of the distal common bile duct[8,9] increased the failure rate of stone retrieval.

In 2003, Ersoz et al[10] recommended a modification of endoscopic papillary balloon dilation which combined large balloon dilation (15-20 mm) with a limited precut of the papilla. It was designed with the aim of reducing adverse events by avoiding a full incision, shortening the procedure time, reducing the use of endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy (EML) and minimizing the adverse events associated with EML[11]. However, it has not been fully accepted by all endoscopists on account of its potential adverse events. A recent meta-analysis revealed that EST plus large balloon dilation was an effective and safe technique based on the pooled rate of clearance at index endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (89%), related pancreatitis (2.7%), and bleeding (1.06%)[12,13]. Some published studies had made a comparison of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation (EPLBD) with EST for extraction of CBD stones, and the outcomes varied among different institutions[14-21]. Thus, it remains controversial whether EPLBD is superior to EST in the retrieval of stones from the CBD, especially large and difficult stones. We performed the present meta-analysis to assess the efficacy and safety of EPLBD by comparing it with EST in patients whose bile duct stones were larger than 10 mm.

First, a literature search was performed in electronic databases including PubMed, Web of Knowledge, EBSCO, the Cochrane Library, and EMBASE up to July 2013. Then, Digestive Disease Week and European Gastroenterology Week meetings were scanned for relevant meeting abstracts. References cited in all retrieved articles were also reviewed for additional articles. The search terms used were “catheterization”, “endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation”, “balloon dilation”, “balloon catheter”, “endoscopic sphincterotomy”, “vater papillotomy”, “sphincterotomy”, “biliary sphincterotomy”, “gallstone”, “common bile duct stone”, “common blie duct calculi”, “choledocholithiasis”. All the above were combined with “AND” or “OR”.

Randomized controlled trials with a full text available that compared the efficacy and safety of EPLBD and EST in the removal of common bile duct stones (≥ 10 mm) were included for further meta-analysis.

Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers (Mei M and Xu ZQ). Both used the same form for extracting relevant data as follows: baseline trial data (e.g., first author, publication year, article type, number of subjects, sex ratio, intervention, number of stones, mean diameter of stones, balloon size in EPLBD, extent of the sphincterotomy in EPLBD); complete stone removal rate; duct clearance in one session; the requirement for mechanical lithotripsy; the adverse events rate (pancreatitis, perforation, bleeding and acute cholangitis)[22]. A third reviewer (Jin PP) joined the discussion to make the final judgment in cases of disagreement.

The Jadad score[23] was applied to assess the quality of the randomized trials by two investigators (Jin PP and Sun LM). The quality was ranked according to three aspects: randomization, double-blindness and description of withdrawals or dropouts. The final score ranged from 0 to 5: a score lower than 2 indicated lower quality whereas studies achieving a score higher than 3 were considered high quality. Again, if disputes arose, resolution would be made after discussion with a third reviewer (Mei M).

Data analysis was conducted with Review Manager (Version 5.1, Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom). The primary outcome was the efficacy of each procedure, including complete stone removal rate, and stone clearance in the first ERCP session. The secondary outcomes were overall requirement for mechanical lithotripsy, the overall post-ERCP adverse event rate, and incidences of pancreatitis, hemorrhage, acute cholangitis and perforation. Comparisons of pooled effects of complete stone removal rate, stone clearance in the first ERCP session, requirement for mechanical lithotripsy, and overall adverse event rate were described by the RR and 95%CI. While separate post-ERCP adverse events were pooled and compared using the Peto OR, because of the small number of events. A statistically significant difference was defined as P < 0.05. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed by the χ2 test with P≤ 0.1 and calculating I2 with a cutoff of ≥ 50%[24]. A fixed effects model was primarily used, and a random effects model was applied when a significant heterogeneity was detected.

Sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the stability of the original pooled outcomes. First, it was carried out by reanalyzing data using another statistical effects model (e.g., switching from the fixed effects model to the random effects model). Then, sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding the study of Oh and Kim, in which EPLBD was conducted without pre-sphincterotomy[16]. If the exclusion of this study did not cause substantial variation from the primary outcome, the study would be kept in the final analyses.

Subgroup analysis was performed to explore the requirement of EML in management of CBD stones whose diameter were larger than 15 mm.

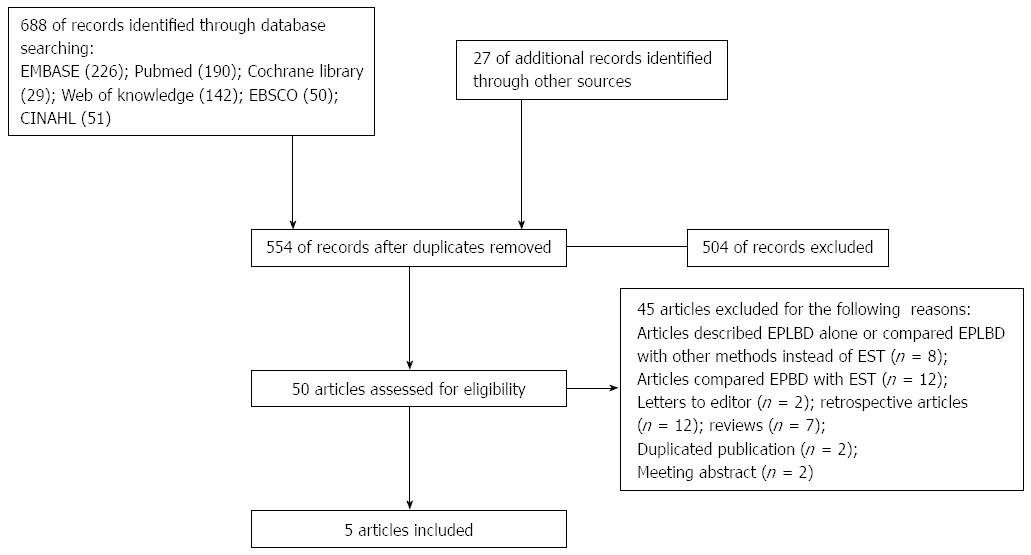

The search of the above-mentioned database yielded 715 articles, and 161 articles were excluded because of duplication. Among the 554 included articles, 504 were further excluded for the following reasons: a review, case series or irrelevant articles, and 50 were potentially included for full text review. Finally, 5 randomized controlled trials (RCTs)[14-16,25,26] with 621 subjects met the inclusion criteria and were selected for evaluation and analysis. The detailed procedure of literature searching is shown in Figure 1. The baseline characteristics of all articles were listed in Table 1. The quality of the 5 RCTs was assessed with the Jadad score. As shown in Table 2, all included studies had a final score ≥ 3 and were of high quality.

| Ref. | Sex (male/female) | Intervention | Mean diameter of stones (mm) | Mean number of CBD stones | Balloon size (mm) in EPLBD | Extent of sphincterotomy in EPLBD | |||

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 1 | Group 2 | ||||

| Qian et al[25], 2013 | 32/31 | 36/33 | Group 1 small EST plus EPLBD (n = 63) | 20.6 ± 5.4 | 20.3 ± 5.3 | 2.2 ± 1.2 | 2.3 ± 1.3 | 12-20 | Limited to one-third that in the minor EST group |

| Group 2 conventional EST (n = 69) | |||||||||

| Teoh et al[26], 2012 | 32/41 | 40/38 | Group 1 limited EST plus EPLBD (n = 73) | 12.47 | 13.26 | ≥ 1 | ≥ 1 | ≤ 15 | One third to one half of the size of papilla |

| Group 2 complete EST (n = 78) | |||||||||

| Oh et al[16], 2012 | 20/20 | 23/20 | Group 1 EPLBD alone (n = 40) | 13.2 ± 3.6 | 13.1 ± 3.9 | NA | NA | 10-18 | No precut |

| Group 2 EST (n = 43) | |||||||||

| Kim et al[15], 2009 | NA | NA | Group 1 small EST plus ELPBD (n = 27) | 20.8 ± 4.1 | 21.3 ± 5.2 | 2.2 ± 1.3 | 2.3 ± 1.2 | 15-18 | Mid-portion of papilla |

| Group 2 EST alone (n = 28) | |||||||||

| Heo et al[14], 2007 | 48/52 | 50/50 | Group 1 EST plus EPLBD (n = 100) | 16.0 ± 0.7 | 15.0 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 2.7 | 2.2 ± 1.9 | 12-20 | A third of the size of EST group |

| Group 2 EST alone (n = 100) | |||||||||

| Ref. | Jadad score of RCTs | Article type | Score | ||

| Randomization | Blindness | Withdrawal | |||

| Qian et al[25], 2013 | Appropriate | NA | Clear | Full text | 3 |

| Teoh et al[26], 2012 | Appropriate | Double | Clear | Full text | 5 |

| Oh et al[16], 2012 | Appropriate | Single | Clear | Full text | 4 |

| Kim et al[15], 2009 | Appropriate | NA | Clear | Full text | 3 |

| Heo et al[14], 2007 | Appropriate | NA | Clear | Full text | 3 |

Complete stone removal rate and complete duct clearance in one session: All 5 RCTs had reported a comparison of the outcomes of EPLBD and EST as complete stone removal rate and complete duct clearance in one session. Only one trial by Qian et al[25] reported significant superiority of EPLBD in the first session for complete duct clearance (80.9% vs 60.8%, P = 0.046). While no heterogeneity was found in our meta-analysis in either of the aspects above, a fixed effects model was applied. The pooled outcomes demonstrated similar efficacy of EPLBD and EST in complete CBD stone clearance (93.7% vs 92.5%, P = 0.54) and complete duct clearance in one session (82.2% vs 77.7%, P = 0.17), as shown in Table 3.

| Items | Incidence of | Number of subjects | Hetero-geneity I2 (P) | Analysis model | Test for overall effect | RR/Peto OR (95%CI) | ||

| EPLBD | EST | Z | P value | |||||

| (n = 303) | (n = 318) | |||||||

| Complete stone removal rate | 93.7 (284) | 92.5 (294) | 621 | 0% (0.82) | Fixed | 0.61 | 0.54 | RR = 1.01 |

| (M-H) | (0.97-1.06) | |||||||

| Complete ductal clearance in one session | 82.2 (249) | 77.7 (247) | 621 | 44% (0.13) | Fixed | 1.36 | 0.17 | RR = 1.06 |

| (M-H) | (0.98-1.14) | |||||||

| Requirement for EML | 15.5 (47) | 25.2 (80) | 621 | 10% (0.35) | Fixed | 2.98 | 0.003a | RR = 0.62 |

| (M-H) | (0.45-0.85) | |||||||

| Overall Adverse events | 7.9 (24) | 10.7 (34) | 621 | 0% (0.97) | Fixed | 1.16 | 0.25 | RR = 0.75 |

| (M-H) | (0.46-1.22) | |||||||

| Post-ERCP pancreatitis | 4.0 (12) | 5.0 (16) | 621 | 0% (0.98) | Peto | 0.62 | 0.54 | Peto OR = 0.79 |

| (0.37-1.68) | ||||||||

| Hemorrhage | 1.7 (5) | 2.8 (9) | 621 | 28% (0.25) | Peto | 1.00 | 0.32 | Peto OR = 0.57 |

| (0.19-1.71) | ||||||||

| Perforation | 0.3 (1) | 0.9 (3) | 621 | 34% (0.22) | Peto | 0.93 | 0.35 | Peto OR = 0.39 |

| (0.06-2.81) | ||||||||

| Acute cholangitis | 1.3 (4) | 1.3 (4) | 621 | 0% (0.71) | Peto | 0.11 | 0.92 | Peto OR = 1.08 |

| (0.27-4.37) | ||||||||

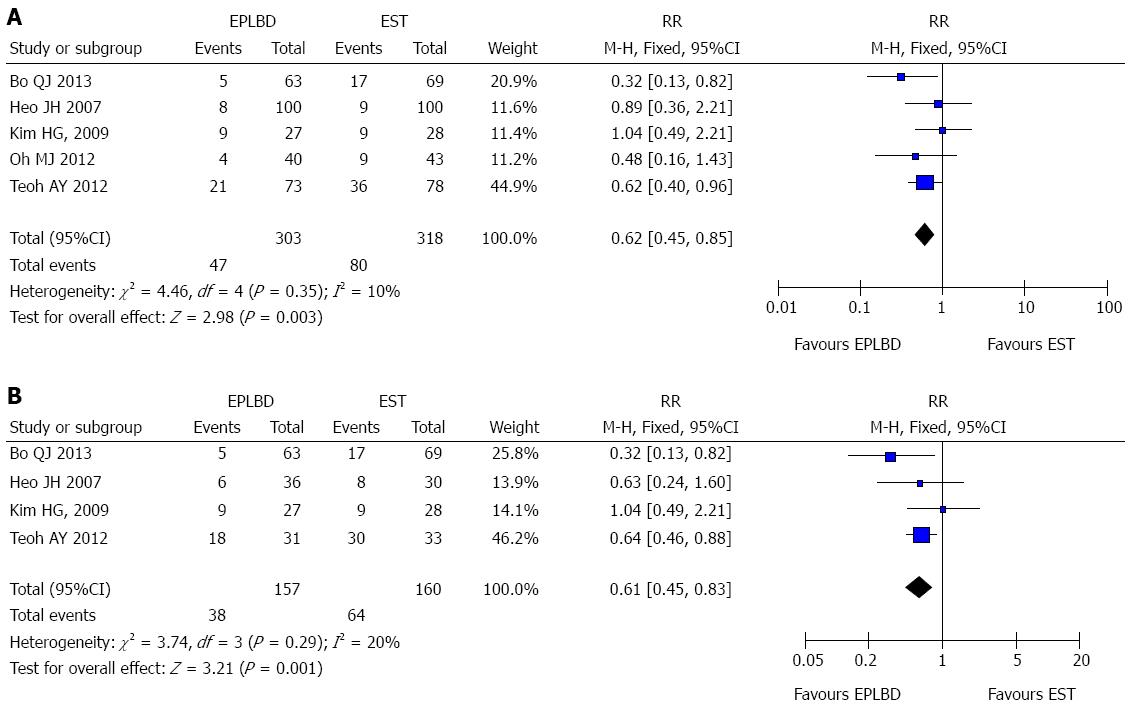

Requirement for mechanical lithotripsy: All the included articles provided data on the use of EML. Two articles[25,26] mentioned the difference between EPLBD and EST (P < 0.05). The pooled outcome of the current analysis implied that EPLBD might reduce the need for EML when compared with EST in the management of CBD stones (15.5% vs 25.2%, P = 0.003) (See Figure 2A). No heterogeneity was detected.

Overall adverse events: Adverse events overall included procedure-related pancreatitis, hemorrhage, perforation, acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. Morbidities in the 5 RCTs were all defined and graded according to the modified 1991 Cotton consensus[22]. One trial[15] mentioned that no adverse events occurred with either EPLBD or EST (0/27 vs 0/28). In the light of the pooled RR of our current meta-analysis (RR = 0.75; 95%CI: 0.46-1.22), the overall adverse event rates showed similar rates for EPLBD compared with EST. This conclusion was consistent with that in each article included.

Analysis of the separate postoperative adverse events: Procedure-related pancreatitis was defined as epigastric pain for more than 24 h duration with at least a 3-fold elevation in serum amylase and/or lipase concentration. Hemorrhage was defined as a decrease in hemoglobin concentration of > 2 g/dL or clinical manifestation of bleeding (not only endoscopic) after the procedure, such as melena or hematemesis[22]. Cholangitis was considered when the temperature was above 38 °C and accompanied by right upper quadrant pain[22]. Given the rare incidence of these adverse events, the Peto OR method was used. No statistically significant difference was found in terms of post-ERCP pancreatitis (Peto OR = 0.79; 95%CI: 0.37-1.68), hemorrhage (Peto OR = 0.57; 95%CI: 0.19-1.71), cholangitis (Peto OR = 1.08; 95%CI: 0.27-4.37) or perforation (Peto OR = 0.39; 95%CI: 0.06-2.81) for EPLBD compared with EST, as shown in Table 3.

Final conclusions were not altered when the results were reanalyzed by the random effects model. Moreover, both primary and secondary outcomes showed no substantial change after we eliminated the trial by Oh and Kim[16]. Only the heterogeneity of complete duct clearance in one session increased (I2 = 58%, P = 0.07), so we had to use the random effects model, as shown in Table 4.

| Items | Adjusted pooled outcome of RCTs with article excluded | ||

| Heterogeneity I2 (P) | P value | RR or Peto OR (95%CI) | |

| Complete stone removal rate | 0% (0.70) | 0.63 | 1.01 (0.97-1.06) |

| Complete ductal clearance in one session | 58% (0.07) | 0.37 | 1.06 (0.93-1.22) |

| Requirement of EML | 27% (0.25) | 0.007a | 0.64 (0. 46-0.89) |

| Overall adverse events | 0% (1.00) | 0.24 | 0.69 (0.37-1.29) |

| Post-ERCP pancreatitis | 0% (0.93) | 0.61 | 0.80 (0.35-1.86) |

| hemorrhage | 35% (0.22) | 0.68 | 0.69 (0.12-4.01) |

| perforation | 0% (0.99) | 0.09 | 0.14 (0.01-1.40) |

| Acute cholangitis | 0% (0.70) | 0.72 | 0.72 (0.12-4.20) |

Four RCTs reported the need for EML in retrieval of large sized stones (≥ 15 mm). The heterogeneity was acceptable with χ2 = 3.74, I2 = 20%, and P = 0.29. The fixed effects model of the pooled outcome (24.2% vs 40%, P = 0.001) revealed that EPLBD was superior to EST in reducing the use of EML for large stones as shown in Figure 2B.

EPLBD is an effective and safe approach for the extraction of large CBD stones (≥ 10 mm). It facilitates stone removal, but not at the expense of increased pancreatitis, hemorrhage and use of EML.

In previous retrospective articles, EPLBD was reported to be more efficient than EST in initial CBD stone clearance (P < 0.05)[18,19,21], while our current meta-analysis of RCTs suggested that EPLBD achieved equivalent success to EST both for complete stone removal or stone clearance in the first session. It was consistent with a former meta-analysis by Feng et al[27], but in contrast with the meta-analysis of 6 retrospective articles by Liu et al[28]. The reason for this discrepancy is possibly related to study design including sample size, the extent of EST, the size or shape of the stone or CBD, the papillary balloon and the operator’s personal experience.

EML might be performed less in EPLBD than EST based on our pooled outcome. EML is generally used in cases of failed stone removal using the Dormia basket. However, disadvantages such as lengthy procedure time, possible injury of the EST site or CBD as a result of using accessories, and impaction of the stone-capturing basket[11] hampered its wide application. Stefanidis et al[29] compared EPLBD plus EST with EML plus EST in a RCT, where similar efficacy was found but there was a higher frequency of adverse events in the latter. This raised the question whether EPLBD could reduce the use of EML. Though a few of the studies[18-21,25,26,30] tried to explore this, no definite consensus has been reached up to now. Even in 2 previous meta-analyses, different outcomes were achieved. The need for EML in our review was significantly reduced with EPLBD compared to EST. The same conclusion was also made for large stones (≥ 15 mm). The possible explanation was that a large diameter balloon could tear the sphincter and offer a more adequate orifice for removal of large stones[27]. However, the requirement for EML might depend on stone size, the extent of EST, the shape of stones and the bile duct[14]. Therefore, EML could still be applied when large balloon dilation by itself could not stretch the distal bile duct wall enough to be effective for removal of large stones[15].

Regarding safety, our meta-analysis suggested that EPLBD did not increase the frequency of overall adverse events, or any single one.

To our knowledge, the common maximum balloon diameter adopted in EPBD was 10 mm. In EPLBD, the balloon was enlarged to 12 to 20 mm or more, which resulted in a major concern of pancreatitis. The balloon size in our included RCTs ranged from 10 to 20 mm as shown in Table 1. However, there was no increase in pancreatitis observed (EPLBD vs EST, 4.0% vs 5.0%, P = 0.54). One explanation might be that a prior EST helps to separate the pancreatic orifice from the biliary orifice and guide the orientation of the dilated balloon towards the CBD, thus preventing pressure overload on the main pancreatic duct[18,20]. The other possible reason may be the longstanding CBD stones which lead to the dilation of CBD and make the papillary orifice persistently open[16]. In addition, the inflation time in the 5 full texts[14-16,25,26] were set around 30-60 s. Pancreatitis may not happen within this time frame. It is speculated that post-procedure pancreatitis might not be associated with larger balloon size, but related more to longer procedure time and a less dilated CBD[31].

Although no statistically significant difference was found, hemorrhage seemed to occur less often in EPLBD (1.7% vs 2.8%). It may be attributed to the partial precut before large balloon insertion, which has an advantage over a major incision for EST, since the possibility of cutting the large vessel in the papillary roof is reduced. Meanwhile, some intra-procedural bleeding can be more easily controlled in the procedure of EST plus EPLBD owing to balloon tamponade of the sphincterotomy site. Furthermore, EPLBD could be performed without prior EST, and large balloon dilation alone had good efficacy and safety for patients with periampullary diverticula and Billroth II gastrectomy[32-34]. Therefore, it might be attractive for patients with a bleeding tendency and cirrhosis, as well as for those with anatomical problems. However, further clinical trials are expected to confirm this conclusion.

The most serious adverse event of EPLBD may be perforation and it is more likely to occur in those with a distal CBD stricture[11,20]. Thus, appropriate patient selection becomes important. Generally, patients targeted for EPLBD may be those with CBD dilation but without strictures of the distal CBD[35], and the size of the selected balloon should not exceed the maximal diameter of the CBD. The advantage of EPLBD is that endoscopists can directly observe the remaining intact mucosa during gradual balloon inflation after partial EST, which helps to minimize the risk of perforation by avoiding excessive pressure[35]. The frequency of cholangitis did not seem to increase after EPLBD. This may due to the wider papillary access achieved with large balloon inflation and effective biliary drainage, both of which contribute to prevent the obstruction of the ampullary orifice and relieve papillary edema.

Long-term complications such as sphincter dysfunction could not be compared in the current meta-analysis, because of the short duration of follow-up in all articles included. However, Lee et al[11] had mentioned in his review that EPLBD might not preserve the function of the sphincter of Oddi, but may cause an even worse condition than EST. The pressure gradient between the CBD and the duodenum will probably be eliminated after EPLBD, just as with surgical sphincteroplasty. So far, there has been no relevant RCT or evidence to confirm this claim.

It is important to point out that an operator’s proficiency of EPLBD or EST might give rise to a different result of overall stone clearance rate and adverse event rate. Operators with experience of at least 100 procedures were more likely to achieve a safe precut sphincterotomy[36]. In our present review, only one article by Heo et al[14] referred to the background of endoscopists, with performance of more than 300 biliary interventions per year. Others did not mention or simply mentioned “experienced endoscopists”. Thus, the varying personal experience in the 2 techniques may have a potential influence over the outcome of successful stone clearance and adverse event rates.

Several limitations existed in the current meta-analysis. Firstly, the EPLBD group consisted of 2 different surgical methods (EPLBD with pre-cut and EPLBD alone), which likely caused a potential bias. Even though our pooled outcomes showed no substantial changes in the later sensitivity analysis when the trial of EPLBD alone was excluded, whether single EPLBD is similar to EST plus EPLBD needs further investigation. Secondly, EPLBD was first advocated in 2003 and has become popular in recent years, therefore, the number of RCTs comparing EPLBD and EST was limited (less than 10). As a result, a funnel plot could not be performed to test publication bias in the current meta-analysis. Thirdly, the 5 RCTs were mainly carried out in China and South Korea. Thus, relevant research, especially from Western countries is warranted to enhance the reliability of the conclusion. Finally, reports in languages other than English were excluded. The risk of language bias had to be considered, but it may not result in any notable bias in the assessment of interventional effectiveness.

In summary, EPLBD is an excellent option in managing difficult CBD stones. Given the minor incision necessary, the reduced requirement for EML and the low frequency of adverse events, EPLBD may be prospectively applied in patients with complicated papillary anatomy, coagulopathy or those who cannot tolerate EST or endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for any other reasons. Further investigation is required to confirm the current conclusions.

Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation (EPLBD) is a newly developed technique applied in retrieval of large common bile duct (CBD) stones (≥ 10 mm). Generally, a balloon with a diameter of 12-20 mm would be used to dilate the CBD after limited pre-cutting of the papilla. It is believed to combine the advantages of endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) and endoscopic papillary balloon dilation but minimize the complications of both.

The comparison of the efficacy and safety of EPLBD and EST showed different outcomes in previous trials. The authors performed a meta-analysis of RCTs to explore whether EPLBD is comparable or superior to EST in the extraction of CBD stones.

In the current review, the pooled outcome of 5 RCTs showed that EPLBD was as efficient as EST in stone removal. Although the balloon in EPLBD was enlarged, the frequency of post-ERCP pancreatitis was not increased. The incidences of hemorrhage, perforation and cholangitis after EPLBD were similar to those after EST. Most importantly, there was a lower need for endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy (EML), even in the retrieval of stones larger than 15 mm. This is the first meta-analysis to compare EPLBD with EST based on RCTs. Therefore, it is meaningful, reliable and has high quality.

EPLBD is suggested as an alternative to EST in the extraction of large or difficult CBD stones. When compared with EST, EPLBD appears safe and effective and also decreases the need for EML. In addition, EPLBD could be performed without pre-cutting the papilla, which may be attractive for patients with coagulopathy.

Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation: This technique involves dilation of the biliary sphincter with a balloon typically 6-10 mm in diameter followed by stone extraction. Endoscopic sphincterotomy: This is the most commonly used therapy in the removal of CBD stones. It could eliminate the principal anatomic barrier impeding stone passage by cutting the biliary sphincter and facilitating stone extraction. Endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy: This technique is used to break stones into fragments when the diameter of the CBD stone is larger than the papillary sphincter.

The current meta-analysis is a serious scholarly work. The method is painstaking, objective and scientific. The conclusion is trustworthy. It is a valuable study.

P- Reviewers: Abd Ellatif ME, LiuYB, Lobo D, Wang SJ S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: Cant MR E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Kawai K, Akasaka Y, Murakami K, Tada M, Koli Y. Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the ampulla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc. 1974;20:148-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in RCA: 454] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1690] [Article Influence: 58.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Staritz M, Ewe K, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH. Endoscopic papillary dilatation, a possible alternative to endoscopic papillotomy. Lancet. 1982;1:1306-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Weinberg BM, Shindy W, Lo S. Endoscopic balloon sphincter dilation (sphincteroplasty) versus sphincterotomy for common bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD004890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liu Y, Su P, Lin S, Xiao K, Chen P, An S, Zhi F, Bai Y. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy in the treatment for choledocholithiasis: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:464-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Baron TH, Harewood GC. Endoscopic balloon dilation of the biliary sphincter compared to endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy for removal of common bile duct stones during ERCP: a metaanalysis of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1455-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Attam R, Freeman ML. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation for large common bile duct stones. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:618-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | McHenry L, Lehman G. Difficult bile duct stones. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2006;9:123-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Itoi T, Wang HP. Endoscopic management of bile duct stones. Dig Endosc. 2010;22 Suppl 1:S69-S75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ersoz G, Tekesin O, Ozutemiz AO, Gunsar F. Biliary sphincterotomy plus dilation with a large balloon for bile duct stones that are difficult to extract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:156-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lee D, Lee B. EST, EPBD, and EPLBD (Cut, Stretch, or Both?). New Challenges in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Tokyo: Spring-Verlag Tokyo 2008; 385-397. |

| 12. | Mummadi RR, Fukami N, Shah RJ, Brauer BC, Yen RD, Chen YK. Safety and efficacy of endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) followed by endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation (EPLBD) for extraction of large common bile duct stones (LBDS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:AB161. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Madhoun MF, Wani S, Hong S, Tierney WM, Maple JT. Endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) combined with endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation (EPLBD) reduces the need for mechanical lithotripsy in patients with large bile duct stones: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75 Suppl:381. |

| 14. | Heo JH, Kang DH, Jung HJ, Kwon DS, An JK, Kim BS, Suh KD, Lee SY, Lee JH, Kim GH. Endoscopic sphincterotomy plus large-balloon dilation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of bile-duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:720-76; quiz 768, 771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim HG, Cheon YK, Cho YD, Moon JH, Park do H, Lee TH, Choi HJ, Park SH, Lee JS, Lee MS. Small sphincterotomy combined with endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation versus sphincterotomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4298-4304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Oh MJ, Kim TN. Prospective comparative study of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation and endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of large bile duct stones in patients above 45 years of age. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1071-1077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yoon KT, Jeon TJ, Hong SP, Park JY, Bang S, Park SW, Song SY, Chung JB. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation after limited endoscopic sphincterotomy compared with endoscopic sphincterotomy in the management of common bile duct stone. J Gastroen Hepatol. 2006;21 Suppl s6:A475-A476. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Rosa B, Moutinho Ribeiro P, Rebelo A, Pinto Correia A, Cotter J. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation after sphincterotomy for difficult choledocholithiasis: A case-controlled study. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:211-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kim TH, Oh HJ, Lee JY, Sohn YW. Can a small endoscopic sphincterotomy plus a large-balloon dilation reduce the use of mechanical lithotripsy in patients with large bile duct stones? Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3330-3337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Itoi T, Itokawa F, Sofuni A, Kurihara T, Tsuchiya T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N, Moriyasu F. Endoscopic sphincterotomy combined with large balloon dilation can reduce the procedure time and fluoroscopy time for removal of large bile duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:560-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Bang SJ, Eum JB, Du Jeong I, Jung SW, Shin JW, Park NH, Kim D, Lee JH, Jung YK. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation compared to endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of large common bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65S:AB214. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2037] [Article Influence: 59.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12275] [Cited by in RCA: 12887] [Article Influence: 444.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39087] [Cited by in RCA: 46546] [Article Influence: 2115.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 25. | Qian JB, Xu LH, Chen TM, Gu LG, Yang YY, Lu HS. Small endoscopic sphincterotomy plus large-balloon dilation for removal of large common bile duct stones during ERCP. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29:907-912. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Teoh AY, Cheung FK, Hu B, Pan YM, Lai LH, Chiu PW, Wong SK, Chan FK, Lau JY. Randomized trial of endoscopic sphincterotomy with balloon dilation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy alone for removal of bile duct stones. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:341-345.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Feng Y, Zhu H, Chen X, Xu S, Cheng W, Ni J, Shi R. Comparison of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation and endoscopic sphincterotomy for retrieval of choledocholithiasis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:655-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Liu Y, Su P, Lin Y, Lin S, Xiao K, Chen P, An S, Bai Y, Zhi F. Endoscopic sphincterotomy plus balloon dilation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis: A meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:937-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Stefanidis G, Viazis N, Pleskow D, Manolakopoulos S, Theocharis L, Christodoulou C, Kotsikoros N, Giannousis J, Sgouros S, Rodias M. Large balloon dilation vs. mechanical lithotripsy for the management of large bile duct stones: a prospective randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:278-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kim TH, Oh HJ, Im CJ, Choi CS, Kweon JH, Sohn YW. A comparative study of outcomes between endoscope sphincterotomy plus endoscope papillary large balloon dilatation and endoscopic sphincterotomy alone in patients with large extrahepatic bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:B156. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Youn YH, Lim HC, Jahng JH, Jang SI, You JH, Park JS, Lee SJ, Lee DK. The increase in balloon size to over 15 mm does not affect the development of pancreatitis after endoscopic papillary large balloon dilatation for bile duct stone removal. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1572-1577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kim KH, Kim TN. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation in patients with periampullary diverticula. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:7168-7176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Jang HW, Lee KJ, Jung MJ, Jung JW, Park JY, Park SW, Song SY, Chung JB, Bang S. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilatation alone is safe and effective for the treatment of difficult choledocholithiasis in cases of Billroth II gastrectomy: a single center experience. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1737-1743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Fujisawa T, Kagawa K, Hisatomi K, Kubota K, Nakajima A, Matsuhashi N. Endoscopic papillary large-balloon dilation versus endoscopic papillary regular-balloon dilation for removal of large bile-duct stones. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;Oct 14; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lee DK, Han JW. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation: guidelines for pursuing zero mortality. Clin Endosc. 2012;45:299-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Akaraviputh T, Lohsiriwat V, Swangsri J, Methasate A, Leelakusolvong S, Lertakayamanee N. The learning curve for safety and success of precut sphincterotomy for therapeutic ERCP: a single endoscopist’s experience. Endoscopy. 2008;40:513-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |