Published online May 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i17.5131

Revised: December 25, 2013

Accepted: February 20, 2014

Published online: May 7, 2014

Processing time: 173 Days and 8 Hours

We report the case of a 57-year-old man who was diagnosed with a large unresectable cholangiocarcinoma associated with 2 satellite nodules and without clear margins with the right hepatic vein. Despite 4 cycles of GEMOX (stopped due to a hypertransaminasemia believed to be due to gemcitabine) and 4 cycles of FOLFIRINOX, the tumor remained stable and continued to be considered unresectable. Radioembolization (resin microspheres, SIRS-spheres®) targeting the left liver (474 MBq) and segment IV (440 MBq) was performed. This injection was very well tolerated, and 4 more cycles of FOLFIRINOX were given while waiting for radioembolization efficacy. On computed tomography scan, a partial response was observed; the tumor was far less hypervascularized, and a margin was observed between the tumor and the right hepatic vein. A left hepatectomy enlarged to segment VIII was performed. On pathological exam, most of the tumor was acellular, with dense fibrosis around visible microspheres. Viable cells were observed only at a distance from beads. Radioembolization can be useful in the treatment of cholangiocarcinoma, allowing in some cases a secondary resection.

Core tip: A 57-year-old man with abdominal pain was diagnosed with a large unresectable hepatic tumor. On liver biopsy, this intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma was observed within the normal liver parenchyma. After 2 systemic chemotherapy regimens, the tumor remained stable. A radioembolization (SIRS-Spheres®) delivering 120 Gy to the tumor, 7 Gy to the normal liver and 4 Gy to the lungs was performed. Three months later, the tumor was less vascularized and had shrunk, and a resection could be performed. On pathological examination, most of the tumor was acellular with fibrosis centered on microspheres, and only a few viable cells were noticed.

- Citation: Servajean C, Gilabert M, Piana G, Monges G, Delpero JR, Brenot I, Raoul JL. One case of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma amenable to resection after radioembolization. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(17): 5131-5134

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i17/5131.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i17.5131

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is the second most common primary liver cancer[1,2] after hepatocellular carcinoma, with approximately 10000 new cases/year in Europe[3], and exhibits a dismal prognosis. The incidence of ICC is growing in many countries[4]. Cure can be expected only from surgical resection[5] and in the early stages. However, the vast majority of patients presents with advanced disease or experience tumor recurrence after initial resection. In locally advanced or metastatic patients, systemic chemotherapy combining cisplatin and gemcitabine is the current gold standard[6], but tumor response and overall survival remain poor. Intra-arterial treatment in locally advanced unresectable cases seems promising in cases of liver-confined disease. Radioembolization with 90Y-loaded beads has been reported in a few studies as efficient in ICC. We present the case of a locally advanced ICC receiving systemic chemotherapy without major efficacy, followed by treatment with 90Y radioembolization (resin microspheres) that permitted resection with major (near complete) histologic response related histologically to the radioembolization.

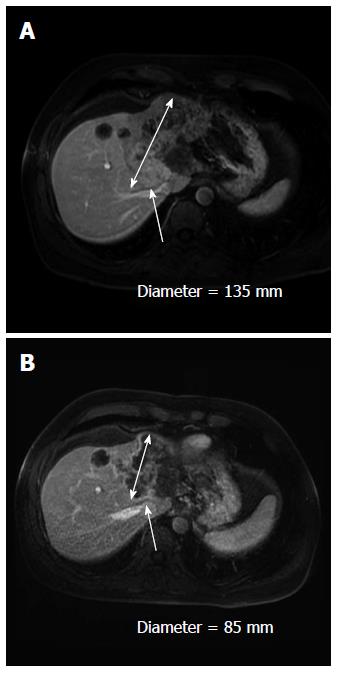

A 57-year-old man without any past history presented with abdominal pain on his right side in December 2011. Ultrasound (US) and computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a large tumor on the median part of the liver without any abdominal lymph nodes or extrahepatic tumors. Alpha-fetoprotein levels were 29 ng/mL (ULN = 5 mg/mL), and carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 serum levels were normal. On magnetic resonance imaging, an 11-cm nodule with two satellite tumors was identified. The main tumor was invading the left portal pedicle and the left and median supra-hepatic veins and exhibited no security margin with the right supra-hepatic vein (Figure 1A) and the right hepatic artery. Colonoscopy and gastroscopy were normal. Pathological analysis of the liver biopsy confirmed an ICC; the surrounding liver parenchyma was normal.

The patient was treated with a GEMOX regimen (gemcitabine 1000 mg/m² D1 and oxaliplatin 100 mg/m² D2) every 2 wk. After the fourth cycle, the appearance of hepatic cytolysis likely due to gemcitabine led us to stop this treatment and to shift to a FOLFIRINOX regimen. After 4 cycles, the CT scan revealed a stable disease, and resection was considered impossible.

Local hepatic treatment with radioembolization was subsequently attempted. A biodistribution analysis of 99 mTc macroaggregated albumin injected in the target arteries did not reveal any lung shunting of extrahepatic uptake. The therapeutic injection was performed on 23rd July 2012 with two selective injections: one in the left hepatic artery of 474 Mbq of 90Y-resin microspheres (SIRS-Spheres®, Sirtex Medical, Lane Cove, Australia) and the other of 440 Mbq in the segment IV artery arising from the right hepatic artery. Dosimetry calculations (BSA method) corresponded to 120 Gy delivered to the tumor, 7 Gy to the non-tumorous liver and 4 Gy to the lungs. No side effects were noted, and 4 more cycles of FOLFIRINOX were administered. In September 2012 (2 mo after the radioembolization), the CT scan revealed a partial response (Figure 1B), but at the arterial phase, the hypervascular component of the tumor had clearly declined, and a margin between the tumor and the right hepatic vein could be observed. The volume of the left lobe only slightly increased after radioembolization from 1323 mL up to 1420 mL.

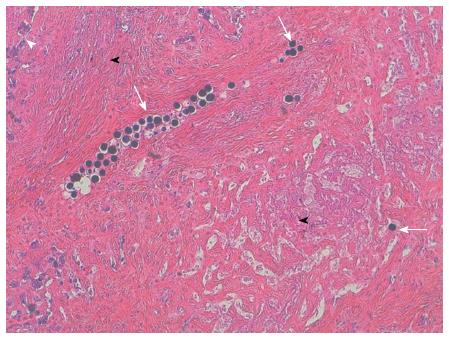

A left hepatectomy enlarged to segment VIII was performed on October 30th, 2012 without major difficulty. The pathological examination revealed that most of the tumor was composed of acellular, dense, collagen fibrosis with many beads included. The center of the tumor was entirely fibrotic; at the periphery of the tumor (Figure 2), some neoplastic cords could be identified in the fibrosis at a distance from beads; these cords were largely unicellular and sometimes organized around a glandular cavity. This response was classified as a major tumoral regression with a R0 resection. The patient was alive without evidence of recurrence 1 year after the surgery.

This case of partial radiologic tumor response allowing a complete R0 tumor resection and major histological tumor response after chemotherapy and one single radioembolization illustrates the usefulness of multidisciplinary approaches in locally advanced liver tumors, particularly ICC, and the efficacy of radioembolization. In this case, pathological examination revealed a close relationship between the presence of beads and severe necrosis/fibrosis; conversely viable tumor cells were only observed at the periphery of the tumor, at considerable distances from beads.

Radioembolization involves the injection of microspheres loaded with 90Y into the feeding artery. These spheres had a diameter ranging from 25 to 60 μm. Currently, two different types of microspheres are available, glass (TheraSphere®, Nordion, Canada) and resin (SIR Sphere, SIRTEX, Australia), and these differ in size and activity per sphere, which is important for glass spheres but less important for resin microspheres. This treatment achieves the microembolization of tumorous vessels and delivers local irradiation; 90Y is a very energetic isotope with a cytotoxic range of several millimeters (median 2.5 mm) and a short half-life of 64.2 h. This isotope is only a beta emitter, and patients can be discharged the same day. This treatment is a therapeutic option in hepatocellular carcinoma and in hepatic colorectal metastases. Large-scale randomized trials are ongoing to determine the best place for these loco-regional treatments.

Few data are available on 90Y radioembolization in advanced cholangiocarcinoma[7-9]; both resin and glass microspheres have been used. All series are retrospective and have confirmed tolerance to this therapeutic option. The response rate is difficult to summarize, as some series used the classical Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST)/WHO criteria, whereas others used EASL criteria or mRECIST more “logically” with this approach to measure the vascularized part of the tumor. The response rate was approximately 25%-30% using WHO or RECIST and higher (73%) with EASL. In one series, 5 of 46 patients benefited from downstaging from an R0 surgery[10], as in our case. In most cases, the future remnant liver volume increased after radioembolization of the contralateral lobe[11]; this increase was not obvious in our case.

Therefore, in unresectable but localized ICC, radioembolization can be considered a useful tool that results in curative resection in some cases. This option should be considered in some borderline cases for surgical resection.

Authors report the case of a 57-year-old man who was diagnosed with a large unresectable cholangiocarcinoma associated with 2 satellite nodules and without clear margins with the right hepatic vein.

Despite 4 cycles of GEMOX (stopped due to a hypertransaminasemia believed to be due to gemcitabine) and 4 cycles of FOLFIRINOX, the tumor remained stable and continued to be considered unresectable. Radioembolization (resin microspheres, SIRS-spheres®) targeting the left liver (474 MBq) and segment IV (440 MBq) was performed.

On computed tomography scan, a partial response was observed; the tumor was far less hypervascularized, and a margin was observed between the tumor and the right hepatic vein. A left hepatectomy enlarged to segment VIII was performed.

Radioembolization can be useful in the treatment of cholangiocarcinoma, allowing in some cases a secondary resection.

Interesting case report dealing with the value of radioembolization in the treatment of initially unresectable CCC. Useful aspect of a multimodal pathway.

P- Reviewers: Chetty R, Detry O, Izbicki JR, Lau WYJ, Pinlaor S, Ramia JM, Shindoh J S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Khan SA, Thomas HC, Davidson BR, Taylor-Robinson SD. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet. 2005;366:1303-1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 872] [Cited by in RCA: 899] [Article Influence: 45.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Blechacz B, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma: advances in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Hepatology. 2008;48:308-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 553] [Cited by in RCA: 536] [Article Influence: 31.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Parkin DM, Whelan SL, Ferlay J, Teppo L, Thomas DB. Cancer incidence in five continents, vol VIII. Lyon: IARC Press 2002; 155. |

| 4. | Shaib YH, Davila JA, McGlynn K, El-Serag HB. Rising incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a true increase? J Hepatol. 2004;40:472-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in RCA: 543] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Casavilla FA, Marsh JW, Iwatsuki S, Todo S, Lee RG, Madariaga JR, Pinna A, Dvorchik I, Fung JJ, Starzl TE. Hepatic resection and transplantation for peripheral cholangiocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:429-436. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, Madhusudan S, Iveson T, Hughes S, Pereira SP. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273-1281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2617] [Cited by in RCA: 3167] [Article Influence: 211.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Saxena A, Bester L, Chua TC, Chu FC, Morris DL. Yttrium-90 radiotherapy for unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a preliminary assessment of this novel treatment option. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:484-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hyder O, Marsh JW, Salem R, Petre EN, Kalva S, Liapi E, Cosgrove D, Neal D, Kamel I, Zhu AX. Intra-arterial therapy for advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a multi-institutional analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:3779-3786. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Rafi S, Piduru SM, El-Rayes B, Kauh JS, Kooby DA, Sarmiento JM, Kim HS. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for unresectable standard-chemorefractory intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: survival, efficacy, and safety study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36:440-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mouli S, Memon K, Baker T, Benson AB, Mulcahy MF, Gupta R, Ryu RK, Salem R, Lewandowski RJ. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: safety, response, and survival analysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24:1227-1234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Edeline J, Lenoir L, Boudjema K, Rolland Y, Boulic A, Le Du F, Pracht M, Raoul JL, Clément B, Garin E. Volumetric changes after (90)y radioembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: an option to portal vein embolization in a preoperative setting? Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2518-2525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |