Published online Apr 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i16.4745

Revised: January 13, 2014

Accepted: February 26, 2014

Published online: April 28, 2014

Processing time: 195 Days and 9.6 Hours

AIM: To investigate the short-term and long-term efficacy of entecavir versus lamivudine in patients with spontaneous reactivation of hepatitis B presenting as acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF).

METHODS: This was a single center, prospective cohort study. Eligible, consecutive hospitalized patients received either entecavir 0.5 mg/d or lamivudine 100 mg/d. All patients were given standard comprehensive internal medicine. The primary endpoint was survival rate at day 60, and secondary endpoints were reduction in hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, and improvement in Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores at day 60 and survival rate at week 52.

RESULTS: One hundred and nineteen eligible subjects were recruited from 176 patients with severe acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B: 65 were included in the entecavir group and 54 in the lamivudine group (full analysis set). No significant differences were found in patient baseline clinical parameters. At day 60, entecavir did not improve the probability of survival (P = 0.066), despite resulting in faster virological suppression (P < 0.001), higher rates of virological response (P < 0.05) and greater reductions in the CTP and MELD scores (all P < 0.05) than lamivudine. Intriguingly, at week 52, the probability of survival was higher in the entecavir group than in the lamivudine group [42/65 (64.6%) vs 26/54 (48.1%), respectively; P = 0.038]. The pretreatment MELD score (B, 1.357; 95%Cl: 2.138-7.062; P = 0.000) and virological response at day 30 (B, 1.556; 95%Cl: 1.811-12.411; P =0.002), were found to be good predictors for 52-wk survival.

CONCLUSION: Entecavir significantly reduced HBV DNA levels, decreased the CTP and MELD scores, and thereby improved the long-term survival rate in patients with spontaneous reactivation of hepatitis B presenting as ACLF.

Core tip: This study compared the short-term and long-term efficacy of entecavir and lamivudine in patients with spontaneous reactivation of hepatitis B presenting as acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). Entecavir significantly reduced hepatitis B virus DNA levels, decreased the Child-Turcotte-Pugh and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores, and thereby improved the long-term survival rate in patients with spontaneous reactivation of hepatitis B presenting as ACLF. Pretreatment MELD score and virological response at 30 d were good predictors of long-term survival.

-

Citation: Zhang Y, Hu XY, Zhong S, Yang F, Zhou TY, Chen G, Wang YY, Luo JX. Entecavir

vs lamivudine therapy for naïve patients with spontaneous reactivation of hepatitis B presenting as acute-on-chronic liver failure. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(16): 4745-4752 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i16/4745.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i16.4745

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is a major type of liver failure in the Asian region. The incidence of ACLF was reported as 91.7% in an epidemiological investigation from China[1]. ACLF has an extremely high short-term mortality rate, ranging from 50%-90%[2,3], and 77% of patients died of multi-organ failure[4]. Liver transplantation is the definitive therapy, but is limited by donor shortage and high costs[5,6]. Thus, it is necessary to explore other effective therapies, especially in patients without liver transplantation.

In China, chronic HBV infection is the cause of approximately 90% of ACLF[1]. In these patients, severe acute exacerbation (SAE) of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) often occurs spontaneously: it was seen in 15%-37% of patients with chronic HBV infection after 4 years of follow-up[7]. Although there is no consensus definition of SAE, it usually refers to the abrupt reappearance or rise in serum hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA in a patient with previously inactivated or resolved HBV infection[8]. A high HBV DNA level (> 105 copies/mL) was suggested as useful to identify SAE of CHB in a previous study[9]. Continuous high levels of viral replication is one of the key factors causing severe liver damage[10]. Therefore, antiviral treatment should be promptly instituted.

Lamivudine is the first approved oral therapy for anti-HBV treatment, and has an excellent safety and tolerability profile. Early studies e proved that the potential short-term benefits of lamivudine in patients with the disease are superior to historical controls[11,12]. However, prolonged lamivudine monotherapy has been found to be associated with an increased risk of re-exacerbation after temporary relief of the initial SAE, because of treatment-induced HBV variants with YMDD mutations[13,14]. Entecavir is another oral anti-HBV compound with potent activity. Its in vitro potency is 100- to 1000-fold greater than that of lamivudine[15]. Furthermore, the cumulative rate of resistance to entecavir was only 1.2% in 5 years[16]. Theoretically, entecavir may be more suitable for the long-term treatment of ACLF because of severe reactivation of HBV.

However, the lack of large sample sizes, contemporary controls and long-term research, has lead to inconsistent clinical data with regard to the efficacy and safety of entecavir in these studies. This prospective cohort study was performed to compare the efficacy of entecavir and lamivudine in terms of the reduction in HBV DNA levels, improvement in biochemical and disease severity, likely improvement in survival and to identify prognostic factors in patients with severe reactivation of HBV presenting as ACLF.

In this prospective cohort study, eligible consecutive hospitalized patients with ACLF were recruited from the Department of Infectious Diseases, Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), from November 2007 to July 2011. All recruited patients were examined by clinicians and were enrolled into the study according to the criteria of ACLF[17]. The inclusion criteria were: (1) age from 18 to 65 years; (2) the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen in the serum for at least 6 mo; (3) HBV DNA level > 105 copies/mL; (4) alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level > 5 times the upper limit of normal; and (5) acute hepatic insult manifesting as jaundice (serum total bilirubin ≥ 171 μmol/L or a daily increase ≥ 17.1 μmol/L) and coagulopathy [international normalized ratio (INR) ≥ 1.5 or prothrombin activity < 40%], complicated within 4 wk by ascites and/or encephalopathy. The exclusion criteria were: (1) super-infection or co-infection with hepatitis A, C, D, E viruses, or human immunodeficiency virus; (2) coexistence of any other liver diseases, such as autoimmune hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, drug hepatitis or Wilson’s disease; (3) hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosed by computed tomography; (4) coexistence of any other serious systemic or psychiatric diseases; (5) jaundice caused by obstructive or hemolytic diseases; (6) prolonged prothrombin time induced by blood system disease; and (7) a previous course of any antiviral, immunomodulator or cytotoxic/immunosuppressive therapy for chronic hepatitis or other illnesses within at least the preceding 12 mo.

The study protocol was in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. The ethics committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu University of TCM approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient or their relatives before enrollment. Furthermore, the non-availability of artificial liver support therapy and liver transplantation facilities were also explained to the patients.

This was a prospective cohort study. All consecutive hospitalized patients spontaneously formed two cohorts (entecavir/lamivudine cohort), according to their preferences for antiviral therapy. Eligible subjects were given comprehensive internal medicine for 60 d (study period), and were followed up until 52 wk after enrollment (follow-up period) or death.

The sample size was calculated based on the data from previous studies[18,19], which suggested a survival rate in the lamivudine-treated group of 50% and a survival rate in the entecavir-treated group of approximately 65%. The match ratio was 1:1. The sample size in each group was 54, with a type I error (one-sided) of 5%, and a power of at least 80%[20]. On the assumption of a rate of 10% loss to follow-up, a target sample size of 119 was required.

All eligible patients were requested to accept antiviral treatment both in the study period and in the follow-up period. The entecavir cohort was given entecavir 0.5 mg/d (Baraclude, Bristol-Myers Squibb, China), while the lamivudine cohort was given lamivudine 100 mg/d (QO, GlaxoSmithKline, China). In addition, each patient was given standard comprehensive internal medicine during the study period. This routinely included absolute bed rest, barrier nursing, high calorie diet (35-40 cal/kg per day), lactulose, and intensive care monitoring, intravenous plasma, maintenance water, electrolyte and acid-base equilibrium monitoring, and prevention and treatment of complications. Patients also received albumin, terlipressin, and proton pump inhibitors if required. Enteral or parenteral nutrition was provided for patients whose caloric requirement was not fulfilled by mouth.

Patient clinical and laboratory data were collected prospectively. The latter included: (1) biochemical tests reflecting hepatocyte damage, for example serum ALT, total bilirubin (TBIL), albumin (ALB), and creatinine (CREA), all assayed using a colorimetric method (Automatic Analyzer 7170A, Hitachi, Japan); (2) INR for prothrombin time, performed following the manufacturer’s instructions (STA-evolution, STAGO, France); (3) serum HBV DNA, determined by a fluorescent quantifying polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method with a low limit of detection of 1000 copies/mL (Lightcycler-480, Roche, Switzerland); and (4) HBV markers, for example HBV antigens and antibodies, detected using commercially available enzyme immunoassays (Alisei Quality System, RADIM, Italy).

The severity of liver disease was assessed by the Child-Turcotte Pugh (CTP) score[21] and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score. The MELD score was calculated according to the following equation[22]: 3.78 × ln. [total bilirubin (mg/dL)] + 11.2 × ln INR+ 9.57 × ln [creatinine (mg/dL)] + 6.43 × (constant for liver disease etiology: 0 if cholestatic or alcoholic, 1 otherwise).

Patients were examined every 15 d in the first 60 d, followed by every 3 mo up to 52 wk. Clinical and laboratory data, adverse events, and compliance were monitored during the first 60 d of treatment, and both adverse events and compliance were monitored every 3 mo up to 52 wk.

The primary endpoint of this study was survival rate at day 60. Secondary endpoints were reduction in HBV DNA and ALT levels, and improvement in CTP and MELD scores at day 60, and survival rate at week 52. All patients were followed up and the outcome (recovery, bridging to artificial liver support therapy or liver transplantation, or death) of treatment was recorded. The date and cause of each death were documented.

The patients were questioned regarding adverse events. All adverse events, regardless of their possible association with antiviral drugs, were recorded.

Efficacy and safety analyses were performed according to intention-to-treat (ITT), and were conducted on the full analysis set (FAS). This set principally included the data from all patients receiving at least 1 dose of the study drugs. Partially missing data of the clinical evaluation were carried forward with the principle of the last visit carried forward. Deaths occurring in the study or follow-up period were not regarded as discontinued subjects.

Quantitative data were described by the mean ± SD. Independent-samples t test or Mann-Whitney U tests were performed to compare differences between quantitative data. A χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was performed to calculate differences between qualitative data. A survival curve was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared statistically using a log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to assess the associations between survival and independent variables, and multivariate Cox regression analysis with conditional stepwise forward was then used to calculate the relative risk ratios and 95%CI. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a significance level (P) of 0.05 was used. The statistical tests were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 17.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

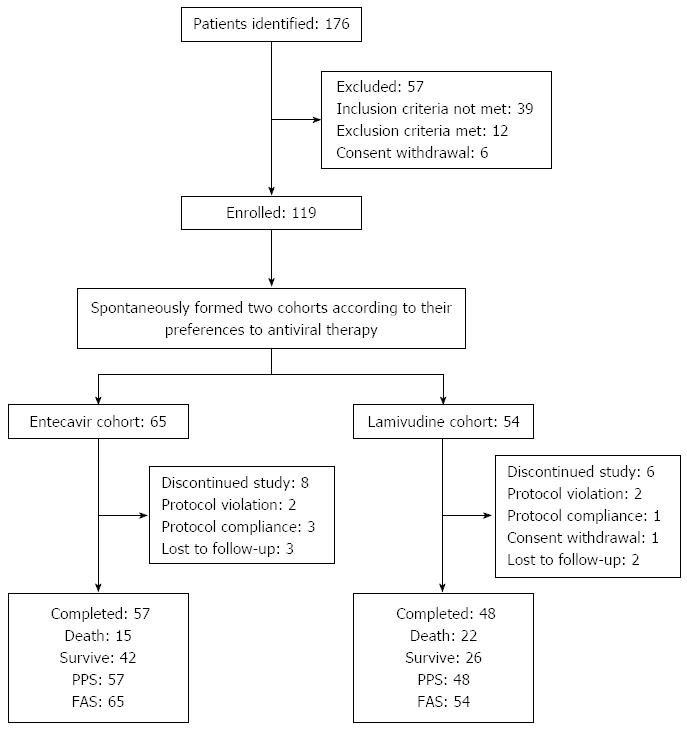

Subject disposition during the study is shown in Figure 1. A total of 176 patients with SAE of CHB were assessed for eligibility, and 119 eligible patients were enrolled. One hundred and five patients completed the study, 57 in the entecavir group and 48 in the lamivudine group. Fourteen patients did not complete the study, but received treatment and had complete observations on at least one related record at a time point; the clinical data of these patients were analyzed on the basis of ITT. The FAS population included 119, with 65 in the entecavir group and 54 in the lamivudine group.

Baseline characteristics of all patients are shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference in age, gender, serum ALT, ALB, TBIL, PTA, CREA, Na, CTP and MELD score, HBV DNA level, HBeAg (±), or complications between the two groups before treatment (all P > 0.05).

| Group | Entecavir (n = 65) | Lamivudine (n = 54) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Age (yr) | 42.8 ± 13.1 | 45.6 ± 11.4 | 1.230 | 0.221 |

| Males | 41 (63.1) | 36 (66.7) | 0.166 | 0.683 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 331.6 ± 74.8 | 320.1 ± 82.4 | 0.797 | 0.427 |

| ALT level (U/L) | 352.5 ± 77.2 | 345.2 ± 89.5 | 0.478 | 0.634 |

| HBeAg-positive | 21 (32.3) | 23 (42.6) | 1.339 | 0.247 |

| anti-HBc IgM | 40 (61.5) | 29 (53.7) | 0.743 | 0.389 |

| HBV DNA (log10 copies/mL) | 7.0 ± 1.4 | 7.2 ± 1.6 | 0.727 | 0.469 |

| Prothrombin activity (%) | 24.7 ± 6.0 | 25.1 ± 5.7 | 0.370 | 0.712 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 28.7 ± 6.9 | 29.4 ± 5.3 | 0.611 | 0.543 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 106.3 ± 42.1 | 109.7 ± 38.6 | 0.455 | 0.650 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 130.6 ± 11.4 | 127.2 ± 12.6 | 1.544 | 0.125 |

| Ascites | 52 (80.0) | 45 (75.9) | 0.217 | 0.641 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 17 (26.2) | 15 (27.8) | 0.040 | 0.842 |

| I-II | 14 (21.5) | 13 (24.1) | 0 | 1 |

| III-IV | 3 (4.6) | 2 (3.7) | 0 | 1 |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 15 (23.1) | 11 (20.4) | 0.127 | 0.722 |

| CTP points | 11.2 ± 2.4 | 10.7 ± 2.1 | 1.196 | 0.234 |

| MELD points | 27.2 ± 6.5 | 26.8 ± 6.3 | 0.339 | 0.735 |

Viral and host responses to nucleoside analog therapy in the two groups are presented in Table 2. Posttreatment HBV DNA levels in the entecavir and lamivudine group were significantly lower than pretreatment levels. Compared with patients in the lamivudine group, patients in the entecavir group had significantly lower HBV DNA levels at days 15, 30, 45, and 60 (all P < 0.001). Undetectable HBV DNA (lower than 1000 copies/mL) was observed in 33 of the 119 (27.7%) patients during treatment, and the entecavir group had a higher proportion of patients achieving undetectable viremia at days 45 and 60 (all P < 0.05). With regard to the ALT response between the two groups, there was a statistical difference at day 15 (P < 0.01), but no significant difference at days 30, 45, and 60 (all P > 0.05).

| Characteristics | Entecavir (n = 65) | Lamivudine (n = 54) | t/χ2/z | P value |

| Virological | ||||

| Serum HBV DNA level (log10 copies/mL) | ||||

| Day 15 | 4.6 ± 1.1 | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 3.790 | < 0.001 |

| Day 30 | 3.9 ± 1.0 | 4.8 ± 1.3 | 4.266 | < 0.001 |

| Day 45 | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 1.0 | 5.454 | < 0.001 |

| Day 60 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 7.653 | < 0.001 |

| Undetectable HBV DNA n (%) | ||||

| Day 15 | 3 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1.024 | 0.312 |

| Day 30 | 15 (23.1) | 6 (11.1) | 2.906 | 0.088 |

| Day 45 | 21 (32.3) | 8 (14.8) | 4.897 | 0.027 |

| Day 60 | 24 (36.9) | 9 (16.7) | 6.039 | 0.014 |

| Biochemical | ||||

| Serum ALT level (U/L) | ||||

| Day 15 | 187.4 ± 67.5 | 231.6 ± 81.1 | 3.231 | 0.002 |

| Day 30 | 86.2 ± 22.4 | 94.7 ± 37.3 | 1.410 | 0.163 |

| Day 45 | 54.4 ± 19.6 | 60.8 ± 28.7 | 1.222 | 0.226 |

| Day 60 | 45.1 ± 20.8 | 51.6 ± 22.3 | 1.455 | 0.149 |

| Severity | ||||

| CTP score | ||||

| Day 15 | 10.4 ± 2.7 | 10.2 ± 3.4 | 0.348 | 0.348 |

| Day 30 | 8.7 ± 3.6 | 9.9 ± 4.2 | 1.678 | 0.096 |

| Day 45 | 7.4 ± 2.1 | 8.5 ± 3.7 | 2.035 | 0.044 |

| Day 60 | 6.6 ± 2.4 | 8.2 ± 3.5 | 2.478 | 0.016 |

| MELD score | ||||

| Day 15 | 25.2 ± 7.1 | 25.7 ± 8.4 | 0.350 | 0.727 |

| Day 30 | 22.6 ± 6.7 | 24.5 ± 7.2 | 1.489 | 0.139 |

| Day 45 | 17.8 ± 7.4 | 20.6 ± 8.2 | 1.956 | 0.052 |

| Day 60 | 13.7 ± 4.6 | 16.1 ± 6.5 | 2.352 | 0.020 |

CTP and MELD scores in both groups of patients are presented in Table 3. Post-treatment CTP and MELD scores in the entecavir and lamivudine group were significantly lower than pretreatment scores. In addition, CTP scores at days 45 and 60 in the entecavir group were superior to those in the lamivudine group, with statistical significance (P < 0.05). Similarly, post-treatment MELD scores in the entecavir group were significantly lower than those in the lamivudine group (P < 0.05).

| Group | Survivors (n = 68) | Non-survivors (n = 51) | t/χ2/z | P value |

| Age (yr) | 39.4 ± 11.7 | 43.2 ± 9.9 | 1.871 | 0.064 |

| Males | 38 (55.9) | 39 (76.5) | 5.409 | 0.020 |

| Platelet count (103/μL) | 93.5 ± 38.2 | 87.3 ± 34.1 | 0.917 | 0.361 |

| ALT level (U/L) | 367.3 ± 80.4 | 345.0 ± 72.6 | 1.560 | 0.121 |

| HBeAg-positive | 20 (29.4) | 24 (47.1) | 3.895 | 0.048 |

| HBV DNA (log10 copies/mL) | 7.2 ± 1.4 | 6.9 ± 1.5 | 1.122 | 0.264 |

| HBV DNA undetectable (< 103 copies/mL) | ||||

| Day 15 | 3 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2.309 | 0.129 |

| Day 30 | 17 (25.0) | 5 (9.8) | 4.466 | 0.035 |

| Day 45 | 20 (29.4) | 9 (17.6) | 2.189 | 0.139 |

| Day 60 | 21 (30.9) | 12 (23.5) | 1.020 | 0.313 |

| Treatment with entecavir | 42(61.8) | 23 (45.1) | 3.266 | 0.071 |

| CTP points (> 10/< 10) | 30/38 | 33/18 | 4.958 | 0.026 |

| MELD points (> 25/< 25) | 28/40 | 32/19 | 5.423 | 0.020 |

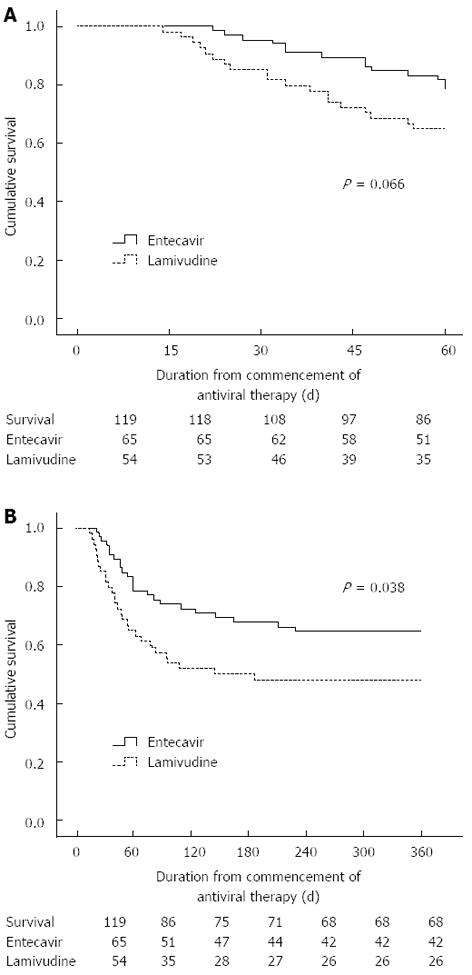

Of the 119 patients in FAS, 51 (78.5%) survived in the entecavir group and 35 (64.8%) survived in the lamivudine group at day 60 (P = 0.066 by log-rank test, Figure 2A). However, at the end of the follow-up period of 52 wk, 42 (64.6%) in the entecavir group and 26 (48.1%) in the lamivudine group survived (P = 0.038 by log-rank test, Figure 2B).

The causes of death were analyzed for 37 patients who had a complete and reliable death record. The major causes were hepatorenal syndrome (8/57, 14.0%), multiple organ failure (3/57, 5.3%), encephalopathy (2/57, 3.5%) and upper gastrointestinal bleeding (2/57, 3.5%) in the entecavir group; hepatorenal syndrome (10/48, 20.8%), multiple organ failure (5/48, 10.4%), encephalopathy (4/48, 8.3%), liver failure (2/48, 4.2%) and upper gastrointestinal bleeding (1/48, 2.1%) in the lamivudine group. There were no significant differences between the two groups (all P > 0.05).

On univariate analysis, gender (P = 0.020), HBeAg (±) (P = 0.048), undetectable HBV DNA at day 30 (P = 0.035), pretreatment CTP score (P = 0.026), and MELD score (P = 0.020) were found to be significantly associated with long-term survival. However, age, platelet count, serum ALT, HBV DNA level, and treatment with entecavir were not associated with fatal outcomes. In the forward Cox regression analysis, pretreatment MELD (B, 1.357; 95%CI: 2.138-7.062; P = 0.000), and undetectable HBV DNA at day 30 (B, 1.556; 95%Cl: 1.811-12.411; P = 0.002) were found to be unfavorable predictors of long-term survival.

None of the patients developed drug-induced severe lactic acidosis or other serious adverse events, and all patients tolerated the therapy without dose modification or early discontinuation.

In this prospective cohort, compared with lamivudine treatment, entecavir treatment did not improve short-term prognosis, despite resulting in faster virological suppression, higher rates of virological response, and a greater reduction in CTP and MELD scores at day 60 in patients with ACLF. Intriguingly, continuation of entecavir treatment significantly benefited 52-wk survival. In addition, pretreatment MELD score and virological response at day 30 were significantly related to long-term prognosis.

Chronic HBV infection is a rapid, dynamic process with vast amounts of virus and infected cells produced and killed each day. When patients with chronic HBV infection receive nucleoside analogs, HBV DNA levels are generally attenuated. Frequent sampling of viral load showed a bi-phasic decline. During the initial phase, the antiviral drug, via almost complete blocking of virus replication in hepatocytes, reduces the release of free virus into the peripheral blood, resulting in a fast decline in serum HBV DNA level. In the subsequent slow viral decline phase, virus-infected liver cells are degraded because of the basic immunity response of the host[23,24]. Thus, early rapid viral decline is dependent on the efficient inhibition of viral production, as determined by the dose and potency of antiviral therapy. As seen in previous studies[25], entecavir, with a stronger and more potent activity, achieved faster viral decline and higher rates of virological response.

In previous studies, early rapid viral decline was reported to be associated with the prognosis of patients with ACLF because of severe reactivation of HBV[26-28]. However, another cohort trial suggested that a fast viral decline conferred no survival benefit and did not prevent rapid progression of the disease to multi-organ failure[18]. In a recent study in Hong Kong, fast viral decline was found to be related to increased 48-wk mortality, which may have led to an exaggerated immune response and exacerbated the liver injury[29]. In the present study, entecavir treatment in patients with ACLF resulting from SAE of CHB rapidly reduced serum HBV DNA levels (P < 0.001), improved the CTP and MELD scores (P = 0.016 and 0.020, respectively) at day 60, and thus reduced 52-wk mortality (P = 0.038).

Host immunity in the pathogenesis of liver failure has been widely recognized. Cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs), the core of cellular immunity, play a key role in the clearance of intracellular virus, which is most closely associated with cell apoptosis or necrosis[30]. High levels of HBV replication is the major pathogenesis of ACLF because of reactivation of hepatitis B. Persistent viral replication causes a vigorous cellular immune response (especially in CTLs), resulting in severe hepatic damage. In this study, antiviral therapy with entecavir, compared with lamivudine, was found to be more effective in improving survival in patients with ACLF. This may be attributed to the weak activity of lamivudine, leading to the delayed commencement (median time 7-30 d) and viral suppression during the initial 4-8 wk of high viral replication[31]. Conversely, entecavir, which is more potent and has lower resistance, was more likely to achieve rapid and persistent action. By rapidly suppressing HBV replication and reducing serum viral load, entecavir lowers the expression of HBV antigens on the liver cell membrane, and consequently partially blocks CTLs from damaging hepatic cells[32]. Furthermore, a continuous decline in serum viral load caused a reduction in the number of infected hepatic cells[24]. This might prevent vigorous immune damage in normal hepatic cells.

Univariate analysis showed that gender, HBeAg status, HBV DNA response status at day 30, CTP and MELD scores were significantly associated with mortality. On multivariate analysis, only pretreatment MELD score and virological response at day 30 were found to be independent predictors of 52-wk survival. A previous study suggested that pretreatment HBV DNA load was related to the prognosis of patients with chronic severe hepatitis B[26]. However, our results showed that there was no significant difference (P = 0.264), despite the higher mean pretreatment HBV DNA load [(7.2 ± 1.4) log10 copies/mL] in survivors than [(6.9 ± 1.5) log10 copies/mL] in non-survivors. This may be correlated with the different baseline information in the subjects, sample size and study design. To obtain a more precise conclusion, more studies with a larger sample size, and a similar subject and trial design are needed. Moreover, it seems that virological response, which occurred late, did not always improve long-term patient survival. This might be associated with severe damage to residual hepatocytes, which limits the regenerative capacity of the liver[33]. Therefore, potent nucleoside drugs, such as entecavir or tenofovir, should be given as quickly as possible.

This study also had some limitations. One limitation of the trial was that grouping was not in accordance with the randomization principle. Effective randomization can eliminate bias in grouping and improve the comparability of research data. The results of randomized, controlled trials (RCT) are considered to be evidence of the highest grade. However, it was not ethical to conduct an ideal RCT for such serious diseases. Therefore, we conducted a prospective cohort study. To accurately estimate the effectiveness of the therapeutic agents and improve the validity of the cohort study, our study was designed using rigorous methods that mimicked those of an RCT, such as inclusion and exclusion criteria, and statistical methods including ITT analysis. Another limitation was the lack of a placebo. Previous studies have indicated that entecavir or lamivudine could effectively improve the prognosis of ACLF patients compared with placebo. In our study, there was no need to repeat this conclusion. Moreover, it was medically unethical that patients with liver failure should undergo placebo therapy. Thus, the trial was designed to directly compare entecavir and lamivudine.

In conclusion, antiviral treatment with entecavir significantly reduced HBV DNA levels, decreased the CTP and MELD scores, and thereby improved the long-term survival rate in patients with spontaneous reactivation of hepatitis B presenting as ACLF. Entecavir was well tolerated throughout the study. Pretreatment MELD score and virological response at day 30 were related to 52-wk survival. To obtain a more objective and accurate conclusion, larger and longer-term multi-center studies are needed. In addition, it is critical to investigate whether combined nucleoside analogs can achieve faster viral decline, and whether relationships exist between the prognosis of patients and host immunity, especially cellular immunity, such as T helper 17 cells, regulatory T cells, and CTLs.

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is a severe clinical syndrome. Spontaneous acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B is a leading cause of ACLF. Liver transplantation is the definitive therapy, but is limited by donor shortage and high costs. Thus, it is necessary to explore other effective therapies.

Lamivudine improved short-term prognosis in ACLF patients. However, continuous lamivudine therapy increased the risk of re-exacerbation after temporary relief, because of hepatitis B virus (HBV) variants with YMDD mutations. Entecavir is another oral anti-HBV compound with potent activity and low resistance. Theoretically, entecavir may be more suitable for the long-term treatment of ACLF due to severe reactivation of HBV.

The present study demonstrates that entecavir significantly reduced HBV DNA levels, decreased the Child-Turcotte-Pugh and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores, and thereby improved the long-term survival rate in patients with spontaneous reactivation of hepatitis B presenting as ACLF. The pretreatment MELD score and virological response at 30 d affected patient survival.

The data from this study provide a rational basis for nucleoside analog treatment in clinical practice for patients with severe reactivation of HBV presenting as ACLF.

ACLF is a clinical syndrome where acute hepatic insult, manifesting as jaundice and coagulopathy, is complicated within 4 wk by ascites and/or encephalopathy in a patient with previously diagnosed or undiagnosed chronic liver disease.

The results in the study are interesting and may help clinicians to select anti-HBV therapy.

P- Reviewers: Akbar SMF, Arai M, Ye XG, Zhao HT S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Stewart GJ E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Liu XY, Hu JH, Wang HF, Chen JM. [Etiological analysis of 1977 patients with acute liver failure, subacute liver failure and acute-on-chronic liver failure]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Zazhi. 2008;16:772-775. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Katoonizadeh A, Laleman W, Verslype C, Wilmer A, Maleux G, Roskams T, Nevens F. Early features of acute-on-chronic alcoholic liver failure: a prospective cohort study. Gut. 2010;59:1561-1569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Evenepoel P, Laleman W, Wilmer A, Claes K, Maes B, Kuypers D, Bammens B, Nevens F, Vanrenterghem Y. Detoxifying capacity and kinetics of prometheus--a new extracorporeal system for the treatment of liver failure. Blood Purif. 2005;23:349-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Garg H, Kumar A, Garg V, Sharma P, Sharma BC, Sarin SK. Clinical profile and predictors of mortality in patients of acute-on-chronic liver failure. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:166-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sass DA, Shakil AO. Fulminant hepatic failure. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:594-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yuan D, Liu F, Wei YG, Li B, Yan LN, Wen TF, Zhao JC, Zeng Y, Chen KF. Adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation for acute liver failure in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:7234-7241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lok AS, Lai CL. Acute exacerbations in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Incidence, predisposing factors and etiology. J Hepatol. 1990;10:29-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lok AS, Lai CL, Wu PC, Leung EK, Lam TS. Spontaneous hepatitis B e antigen to antibody seroconversion and reversion in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1839-1843. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kumar M, Jain S, Sharma BC, Sarin SK. Differentiating acute hepatitis B from the first episode of symptomatic exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:594-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Polson J, Lee WM, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease. AASLD position paper: the management of acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2005;41:1179-1197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 644] [Cited by in RCA: 642] [Article Influence: 32.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chien RN, Lin CH, Liaw YF. The effect of lamivudine therapy in hepatic decompensation during acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2003;38:322-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sun LJ, Yu JW, Zhao YH, Kang P, Li SC. Influential factors of prognosis in lamivudine treatment for patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:583-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Papatheodoridis GV, Dimou E, Papadimitropoulos V. Nucleoside analogues for chronic hepatitis B: antiviral efficacy and viral resistance. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1618-1628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chan HL, Wong VW, Hui AY, Tsang SW, Chan JL, Chan HY, Wong GL, Sung JJ. Long-term lamivudine treatment is associated with a good maintained response in severe acute exacerbation of chronic HBeAg-negative hepatitis B. Antivir Ther. 2006;11:465-471. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Yao G. Entecavir is a potent anti-HBV drug superior to lamivudine: experience from clinical trials in China. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:201-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, Pokornowski KA, Eggers BJ, Fang J, Wichroski MJ, Xu D, Yang J, Wilber RB. Long-term monitoring shows hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naïve patients is rare through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1503-1514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 615] [Cited by in RCA: 633] [Article Influence: 39.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Liver Failure and Artificial Liver Group, Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association; Severe Liver Diseases and Artificial Liver Group, Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association. [Diagnostic and treatment guidelines for liver failure]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Zazhi. 2006;14:643-646. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Cui YL, Yan F, Wang YB, Song XQ, Liu L, Lei XZ, Zheng MH, Tang H, Feng P. Nucleoside analogue can improve the long-term prognosis of patients with hepatitis B virus infection-associated acute on chronic liver failure. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2373-2380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yu S, Jianqin H, Wei W, Jianrong H, Yida Y, Jifang S, Liang Y, Zhi C, Hongyu J. The efficacy and safety of nucleos(t)ide analogues in the treatment of HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure: a meta-analysis. Ann Hepatol. 2013;12:364-372. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd edition. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates 1988; . |

| 21. | Christensen E, Schlichting P, Fauerholdt L, Gluud C, Andersen PK, Juhl E, Poulsen H, Tygstrup N. Prognostic value of Child-Turcotte criteria in medically treated cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1984;4:430-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Gordon FD, Peine CJ, Rank J, ter Borg PC. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology. 2000;31:864-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1967] [Cited by in RCA: 2069] [Article Influence: 82.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tsiang M, Rooney JF, Toole JJ, Gibbs CS. Biphasic clearance kinetics of hepatitis B virus from patients during adefovir dipivoxil therapy. Hepatology. 1999;29:1863-1869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wolters LM, Hansen BE, Niesters HG, Zeuzem S, Schalm SW, de Man RA. Viral dynamics in chronic hepatitis B patients during lamivudine therapy. Liver. 2002;22:121-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, Schiff E, Han KH, Lai CL, Safadi R, Lee SS, Halota W, Goodman Z. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;52:886-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in RCA: 772] [Article Influence: 51.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yu JW, Sun LJ, Zhao YH, Li SC. Prediction value of model for end-stage liver disease scoring system on prognosis in patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure after plasma exchange and lamivudine treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1242-1249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chen L, Zheng CX, Lin MH, Gan QR, Lin RS, Gao HB, Huang JR, Pan C. [The impact of early rapid virological response on the outcomes of hepatitis B associated acute on chronic liver failure during antiviral treatment]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Zazhi. 2011;19:734-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yu JW, Sun LJ, Zhao YH, Kang P, Li SC. The study of efficacy of lamivudine in patients with severe acute hepatitis B. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:775-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lange CM, Bojunga J, Hofmann WP, Wunder K, Mihm U, Zeuzem S, Sarrazin C. Severe lactic acidosis during treatment of chronic hepatitis B with entecavir in patients with impaired liver function. Hepatology. 2009;50:2001-2006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Shimizu Y. T cell immunopathogenesis and immunotherapeutic strategies for chronic hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2443-2451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Garg H, Sarin SK, Kumar M, Garg V, Sharma BC, Kumar A. Tenofovir improves the outcome in patients with spontaneous reactivation of hepatitis B presenting as acute-on-chronic liver failure. Hepatology. 2011;53:774-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Shaikh T, Cooper C. Reassessing the role for lamivudine in chronic hepatitis B infection: a four-year cohort analysis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:148-150. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Organization Committee of 13th Asia-Pacific Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 13th Asia-Pacific Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infection Consensus Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of liver failure. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2013;12:346-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |