Published online Apr 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i16.4718

Revised: January 10, 2014

Accepted: March 5, 2014

Published online: April 28, 2014

Processing time: 186 Days and 12.8 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy of endoscopy with a transparent cap on biopsy positioning in Barrett’s esophagus (BE).

METHODS: One hundred and sixty-eight patients with suspected BE at endoscopy were enrolled in our study from November 2007 to December 2009 and divided into two groups: transparent cap group (n = 60) and control group (n = 108). Endoscopy with or without a transparent cap and subsequent biopsy of suspected lesions were performed by five experienced endoscopists in our hospital. In both groups, two biopsy specimens were taken from each patient, and the columnar epithelium or goblet cells in histological assessment were used as the diagnostic standard for BE.

RESULTS: In the transparent cap group, 41 cases were tongue type, while 17 and two cases were identified as island type and circumferential type, respectively. In the control group, 65 tongue-type cases were confirmed, with 38 island-type and five circumferential-type cases. Moreover, there was no significant difference with regard to the composition of endoscopic BE types in the two groups (P > 0.05). In the biopsy specimens, BE was detected in 50 cases in the transparent cap group (83.3%, 50/60), whereas the detection rate in the control group (69.4%, 75/108) was lower compared to that in the transparent cap group (P < 0.05). In addition, goblet cells were recognized in only eight cases (all with columnar epithelium) (8/60, 13.3%) in the transparent cap group, with 11 cases in the control group.

CONCLUSION: Transparent cap-fitted endoscopy can guide biopsy positioning in BE without other accompanying complications, thus increasing the detection rate of BE.

Core tip: A transparent cap applied to endoscopy can guide biopsy positioning in Barrett’s esophagus without other accompanying complications, thus increasing biopsy accuracy.

- Citation: Chen BL, Xing XB, Wang JH, Feng T, Xiong LS, Wang JP, Cui Y. Improved biopsy accuracy in Barrett’s esophagus with a transparent cap. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(16): 4718-4722

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i16/4718.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i16.4718

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is a premalignant lesion of esophageal carcinoma, with a relative risk of developing adenocarcinoma ranging from 30- to 125-fold higher than in the healthy population[1]. Endoscopy is considered to be an effective approach in the detection of BE. However, even when using current technologies, the detection rate of BE is low, and small lesions, such as tongue-type and island-type, are often missed[2]. In addition, due to frequent cardiac peristalsis, the diagnostic rate of BE is decreased. We found that the use of a transparent cap on the tip of the endoscope can help exposure and retention of lesions in the small lumen in clinical practice. However, there is a lack of statistical data to show whether application of the transparent cap can help biopsy positioning and improve the diagnosis of BE.

Therefore, the goal of this study was to determine whether endoscopy with the transparent cap device was helpful in guiding accurate tissue sampling and increasing BE detection rate without accompanying complications.

BE is the transformation of stratified squamous epithelium into a single layer of columnar epithelium in the lower esophagus, with or without intestinal metaplasia[3]. The presence of specialized intestinal metaplasia is the precancerous state of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Visible extension of the columnar epithelium into the lower esophagus under endoscopy is defined as endoscopically suspected BE[4]. In the present study, endoscopic BE was classified into three types: tongue, island and circumferential, according to the macroscopic appearance of the mucosa[5]. In addition, columnar epithelium identified by histological assessment was a diagnostic criterion for BE[6]. Columnar-lined esophagus was confirmed when the columnar mucosa of the cardiac (junctional), oxyntic or intestinal types was found on biopsy.

We recruited 168 patients (97 male; mean age: 48 years, range: 16-77 years) with endoscopically suspected BE from November 2007 to December 2009. Endoscopy and subsequent biopsy were performed by five experienced endoscopists, two of whom were accustomed to operating endoscopes with a transparent cap. All patients were informed of the purpose of the study and gave signed informed consent, in accordance with the ethics committee guidelines of the hospital.

An Olympus GIF-XQ240, GIF-H20 GASTROSCOPE (Olympus Optical Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), standard biopsy forceps (FB-25k, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and an improved transparent cap with the rigid front-end part clipped with only 2-mm left outside[7] (six-shooter, Saeed Multi-Band Ligator, Wilson-Cook Company, United States) were used in this study (Figure 1).

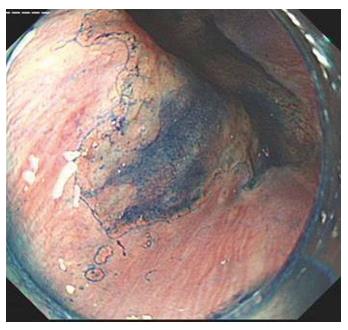

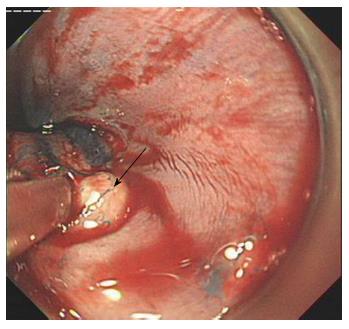

One hundred and sixty-eight patients with suspected BE were randomly allocated to an endoscopist and underwent endoscopy. Sixty patients underwent endoscopy with a transparent cap and 108 cases underwent endoscopy without a cap (control group). In both groups, routine endoscopy without magnification was performed to identify visible mucosal lesions of suspected BE. When lesions were found, the endoscope was retracted and the transparent cap was subsequently installed on the front end of the endoscope in the transparent cap group. When the lesions were large and obvious in some cases, especially the circumferential-type, methylene blue staining was performed to help decide on the biopsy site and improve the detection rate of goblet cells. Two specimens were taken from the suspected BE lesions, fixed in formaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections (4-5 μm thick) were cut for hematoxylin and eosin staining. Histological assessment was undertaken by two experienced gastrointestinal histopathologists.

The data were presented as frequency and analyzed using the χ2 test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

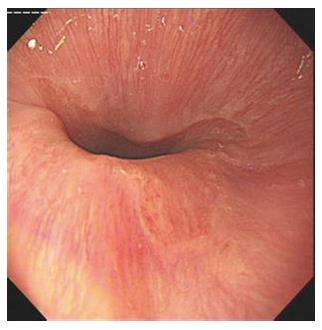

In the transparent cap group, 41 cases were tongue-type, 17 were island-type, and two were circumferential-type. In the control group, 65 tongue-type cases were confirmed, along with 38 island-type and five circumferential-type cases. There was no significant difference with regard to the composition of endoscopic BE types in the two groups (P > 0.05) (Figures 2-5).

Histological assessment revealed that columnar epithelium was found in 50 cases in the transparent cap group (83.3%), with goblet cells present in only eight cases (all with columnar epithelium, 13.3%). In the control group, the detection rate of BE was 69.4% (75/108), which was significantly lower compared to the transparent cap group (P < 0.05). In addition, 11 cases in the control group exhibited goblet cells, accompanied by columnar epithelium (10.2%).

Severe complications, such as massive hemorrhage or perforation, were not observed in either group. However, in the control group, one case demonstrated active hemorrhage from a small blood vessel, and bleeding was subsequently stopped using a titanium clamp. In the transparent cap group, difficulty occurred when the endoscope with the transparent cap passed through the patient’s throat.

Since the 1980s, the prevalence of cancer in the gastric cardia and lower esophagus has shown an increasing trend. Numerous studies have reported that nearly all lower esophageal adenocarcinoma originates from BE, and approximately 40% of cardiac cancer is associated with BE[8]. Therefore, early diagnosis and long-term follow-up of BE are of great importance. Currently, diagnosis and surveillance of BE remain controversial in gastroenterology. A widely accepted and practical definition of BE, which is endorsed by the American College of Gastroenterology, is a change in normal esophageal squamous mucosa (of any length) that is visible endoscopically and demonstrates intestinal metaplasia on biopsy[9]. In the United Kingdom, the presence of intestinal metaplasia is not mandatory for the diagnosis of columnar-lined esophagus, which may be diagnosed when columnar mucosa of cardiac (junctional), oxyntic, or intestinal type is seen on biopsy[10,11]. Recently, Kelty et al[12] found that patients who had glandular mucosa on biopsy, without the presence of intestinal metaplasia, still carried a significant risk of cancer development over their lifetime, and more importantly, it added weight to the argument proposed by the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) that glandular mucosa should still be classified as BE, and such patients should be entered into a surveillance program. This is contrary to the current thinking in the United States, which demands the presence of specialized intestinal metaplasia to make the diagnosis[9]. However, it should be acknowledged that biopsy protocols in the United States are more rigorous than elsewhere. A recent study also demonstrated that a minimum of eight biopsies are required from a columnar-lined esophagus to show intestinal metaplasia[13]. In the present study, the biopsy was performed by experienced endoscopists and a similar number of biopsies were undertaken in each group. However, because the number of biopsies was fewer than that required by present guidelines, only 19 patients were found to have intestinal metaplasia in our study.

To date, the accurate biopsy of suspected lesions is the major approach in BE diagnosis. Prof. Raj Goyal from Harvard Medical School and Prof. Qin Huang from the Pathology Department of Brown Medical School have indicated that multiple repeated biopsies can reduce the misdiagnosis rate, and avoid sampling error. The current international four-quadrant biopsy approach recommends that, due to up-shift of the Z line in BE, endoscopic biopsy specimens should be taken between the Z line and gastroesophageal junction, and four specimens at intervals of 1-2 cm along the major axis of the lesion should be obtained for histological assessment[14]. Therefore, the method and accuracy of biopsy are the basic guarantee of BE diagnosis.

Recently, transparent-cap fitted colonoscopy has been widely used in the screening of colorectal neoplasia based on the following benefits: improving and extending visualization[15-17], shortening cecal intubation[18-20] and reducing patient discomfort[21]. However, the detection rate of adenoma remains controversial. Similarly, due to frequent peristaltic movement of the cardia, endoscopic vision is often unclear, making biopsy difficult and time consuming. We found that the transparent cap helped to expose the mucosa in the lumen with stenosis or frequent peristaltic movement, and guided biopsy positioning in our center[22-24]. The question then arose as to whether the application of the transparent cap could enhance the detection rate of BE on biopsy. We thus used endoscopes with or without transparent caps to perform mucosal biopsy of suspected BE lesions and compared the detection rate of both methods. Using columnar epithelium as the diagnostic standard of BE, application of the transparent cap significantly raised the detection rate from 69.4% to 83.3% in our study. In contrast, the detection rate for goblet cells in the two groups did not differ significantly. The majority of the cases enrolled in this study were tongue- and island-type, increasing the difficulty of biopsy when compared with long-segment circumferential-type lesions. This resulted in difficulty in accurate positioning in the control group, and therefore, the detection rate of BE using a traditional endoscope without a transparent cap might miss several BE cases. In addition, application of the transparent cap did not lead to serious complications such as massive hemorrhage or perforation, indicating the safety of this approach.

High tension in the luminal wall and frequent peristaltic movement of the cardia often result in close contact of the mucosa with the front end of the endoscope, thus blurring vision. This increases the difficulty of observation and biopsy of the lesions, especially small lesions, such as tongue- or island-type, prolongs the operation time, and decreases the accuracy of the biopsy. Installation of a transparent cap protruding 2 cm from the front end of the endoscope leads to clear exposure of the lesion and stability of the front end of the endoscope, thus facilitating the targeted biopsy of suspected BE. Therefore, this approach makes early detection of intestinal epithelium, goblet cells and dysplasia possible, providing a reliable basis for further diagnosis and treatment of BE. However, installation of the transparent cap causes increasing patient discomfort, therefore, patient tolerance should be taken into account and strengthened by improvement of techniques or use of sedatives.

In conclusion, transparent-cap-assisted biopsy improved the detection rate of BE without increasing complications. Although a number of new endoscope-assisted biopsy techniques, such as dye endoscopy, narrow-band endoscopic imaging[25,26], and confocal endoscopy[27], have facilitated biopsy and increased the detection rate of BE in recent years, the application of these techniques remains limited by the required experience of the endoscopist, high cost, and complex manipulation. The transparent-cap-assisted biopsy is more economic, simpler and safer, therefore, this technique is of more practical value and worthy of further promotion in clinical practice.

We gratefully thank our colleagues from our department for their support and suggestions.

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is a premalignant lesion of esophageal carcinoma, with a relative risk of developing adenocarcinoma ranging from 30- to 125-fold higher than in the healthy population. Endoscopy is considered to be an effective approach in the detection of BE. However, even when using current technologies, the detection rate of BE is low, and small lesions, such as tongue- and island-type are often missed. In addition, due to frequent peristalsis of the cardia, the diagnostic rate of BE is decreased.

A transparent cap is widely used for endoscopic variceal ligation. The authors have found that the use of a transparent cap on the tip of an endoscope could help with exposure and retention of lesions in the small lumen in BE in clinical practice. However, there is a lack of statistical data.

To date, accurate biopsy of suspected lesions is the major approach in BE diagnosis. Due to frequent peristaltic movement of the cardia, endoscopic vision is often unclear. The authors found that a transparent cap helped to expose the mucosa in the lumen with stenosis or frequent peristaltic movement, and guided biopsy positioning in clinical practice.

Transparent-cap-fitted endoscopy can guide biopsy accurately in BE without increasing other complications, thus increasing the detection rate of BE.

BE is the transformation of stratified squamous epithelium into a single layer of columnar epithelium in the lower esophagus, with or without intestinal metaplasia. The presence of specialized intestinal metaplasia is the precancerous state of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

This was a good intervention study in which the authors tried to improve the macroscopic evaluation of the distal esophagus regarding BE detection.

P- Reviewers: Guo YM, Hoff DAL, Pace F S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Ackroyd R, Wakefield SE, Williams JL, Stoddard CJ, Reed MW. Surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus: a need for guidelines? Dis Esophagus. 1997;10:185-189. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Levine DS, Haggitt RC, Blount PL, Rabinovitch PS, Rusch VW, Reid BJ. An endoscopic biopsy protocol can differentiate high-grade dysplasia from early adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:40-50. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Spechler SJ. Barrett’s esophagus: the American perspective. Dig Dis. 2013;31:10-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2368] [Cited by in RCA: 2453] [Article Influence: 129.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Herlihy KJ, Orlando RC, Bryson JC, Bozymski EM, Carney CN, Powell DW. Barrett’s esophagus: clinical, endoscopic, histologic, manometric, and electrical potential difference characteristics. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:436-443. [PubMed] |

| 6. | DeVault K, McMahon BP, Celebi A, Costamagna G, Marchese M, Clarke JO, Hejazi RA, McCallum RW, Savarino V, Zentilin P. Defining esophageal landmarks, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and Barrett’s esophagus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1300:278-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cui Y. Improved transparent cap in the application of gastroendoscopy. Zhonghua Xiaohua Neijing Zazhi. 2008;25:380-381. |

| 8. | Hamilton SR, Smith RR, Cameron JL. Prevalence and characteristics of Barrett esophagus in patients with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus or esophagogastric junction. Hum Pathol. 1988;19:942-948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sampliner RE. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis, surveillance, and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1888-1895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 567] [Cited by in RCA: 504] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shepherd NA. Barrett’s esophagus: Its pathology and neoplastic complications. Esophagus. 2003;1:17-29. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Shepherd NA, Hellier MD; British Society of Gastroenterology. Diagnosis of columnar-lined oesophagus. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Columnar-lined Oesophagus. London: BMJ Publishing 2005; 13-17. |

| 12. | Kelty CJ, Gough MD, Van Wyk Q, Stephenson TJ, Ackroyd R. Barrett’s oesophagus: intestinal metaplasia is not essential for cancer risk. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:1271-1274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Harrison R, Perry I, Haddadin W, McDonald S, Bryan R, Abrams K, Sampliner R, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P, Jankowski JA. Detection of intestinal metaplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: an observational comparator study suggests the need for a minimum of eight biopsies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1154-1161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ishaq S, Harper E, Brown J. Survey of current clinical practice in the diagnoisis, management and surveillance of Barrett’s metaplasia: A UK national survey. Gut. 2003;53:A32. |

| 15. | Frieling T, Neuhaus F, Heise J, Kreysel C, Hülsdonk A, Blank M, Czypull M. Cap-assisted colonoscopy (CAC) significantly extends visualization in the right colon. Z Gastroenterol. 2012;50:279-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yap CK, Ng HS. Cap-fitted gastroscopy improves visualization and targeting of lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:93-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Frieling T, Neuhaus F, Kuhlbusch-Zicklam R, Heise J, Kreysel C, Hülsdonk A, Blank M, Czypull M. Prospective and randomized study to evaluate the clinical impact of cap assisted colonoscopy (CAC). Z Gastroenterol. 2013;51:1383-1388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Morgan JL, Thomas K, Braungart S, Nelson RL. Transparent cap colonoscopy versus standard colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:353-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kim HH, Park SJ, Park MI, Moon W, Kim SE. Transparent-cap-fitted colonoscopy shows higher performance with cecal intubation time in difficult cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1953-1958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Morgan J, Thomas K, Lee-Robichaud H, Nelson RL. Transparent Cap Colonoscopy versus Standard Colonoscopy for Investigation of Gastrointestinal Tract Conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD008211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dai J, Feng N, Lu H, Li XB, Yang CH, Ge ZZ. Transparent cap improves patients’ tolerance of colonoscopy and shortens examination time by inexperienced endoscopists. J Dig Dis. 2010;11:364-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhang S, Wang J, Wang J, Zhong B, Chen M, Cui Y. Transparent cap-assisted endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper esophagus: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1339-1342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lei PG, Wu JW, Cui Y, Yan JY, Li QL, Lu LL, Li Q. The value of transparent-cap assisted endoscopy in the diagnosis of esophageal tiny foreign bodies. Zhongguo Yixue Gongcheng. 2008;3:175-176. |

| 24. | Zhang S, Cui Y, Gong X, Gu F, Chen M, Zhong B. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract in South China: a retrospective study of 561 cases. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1305-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Anagnostopoulos GK, Yao K, Kaye P, Hawkey CJ, Ragunath K. Novel endoscopic observation in Barrett’s oesophagus using high resolution magnification endoscopy and narrow band imaging. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:501-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Giacchino M, Bansal A, Kim RE, Singh V, Hall SB, Singh M, Rastogi A, Moloney B, Wani SB, Gaddam S. Clinical utility and interobserver agreement of autofluorescence imaging and magnification narrow-band imaging for the evaluation of Barrett’s esophagus: a prospective tandem study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:711-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Liu H, Li YQ, Yu T, Zhao YA, Zhang JP, Zuo XL, Li CQ, Zhang JN, Guo YT, Zhang TG. Confocal laser endomicroscopy for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Endoscopy. 2009;41:99-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |