Published online Jun 25, 1996. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v2.i2.92

Revised: May 5, 1996

Accepted: May 28, 1996

Published online: June 25, 1996

AIM: To explore and enlarge the application range of laparoscopic video technology in biliary surgery.

METHODS: Since November 1992, 45 cases were treated with laparoscopic video choledocholithotomy T-tube drainage (LCTD) and 5 cases were treated with laparoscopic video choledochojejunostomy (LCJS). The indications and main technical procedures for these two technologies are discussed and presented here.

RESULTS: The LCTD procedure was successfully applied in all 45 cases. One patient with sustained biliary leakage and one patient with sustained residual choledocholith were completely cured. The LCJS procedure was also successfully applied to all 5 cases, and all the patients recovered in a short period without any complications.

CONCLUSION: The results show that LCTD and LCJS are characterized by minor trauma, less sufferings, fast postoperative recovery and good curative effect; these procedures are worth popularizing and extending their application. The laparoscopic video biliary operations that were designed and performed in this study are not only in conformity with the biliary surgical therapeutic principle, but also easy to conduct, economically beneficial, practical and convenient.

- Citation: Xu HB, Xiao YQ, Li WM, Li HC, Tu XQ. Design and performance of laparoscopic video biliary operations. World J Gastroenterol 1996; 2(2): 92-94

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v2/i2/92.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v2.i2.92

Since November 1992, the application range of laparoscopic video technology in biliary surgery has been further explored and enlarged on the basis of successful application of the laparoscopic video cholecystectomy (LC). In our hospital, laparoscopic video biliary operations have been successfully applied, including laparoscopic video choledocholithotomy T-tube drainage (LCTD)[1] for 45 cases and laparoscopic video choledochojejunostomy (LCJS)[2] for 5 cases. The results, for all cases, have been satisfactory. Here, we present these cases and discuss the indications and main technical parameters of LCTD and LCJS.

The instruments used for LCTD included a 25° wide-angle laparoscope (WOLF Co., Germany), an Olympus P-20 choledochofiberscope (Japan), and self-made common additional biliary appliances. The instruments used for LCJS included an Endo GIA, Endo Gauge, Endo Babcock, Endo Retractor and Endo Clip (ETHICON Co., United States), and LCTD instruments.

Under general anesthesia, the patient was placed in the semi-supination position at 20°, inclining to the left at 10°-15° and with a slight elevation of the right lumbar region. After the artificial pneumoperitoneum was established, four trocars were inserted into the abdomen. The viewing incision was located in the lower margin of the umbilicus, and the main operational incision was located at 3 cm under the xiphoid and 3 cm to the right of midline; the two trocars were 1 cm in diameter each. The other two additional incisions were located in the right intercostal midclavicular line and the anterior axillary line; the two trocars were 0.5 cm in diameter each.

For LCJS, the anesthesia, posture and the first four incisions were the same as those described above for LCTD, but the diameter was 1 cm for all. In addition, an insertion incision for Endo GIA was added, located in the intermediate part of the straight muscle of the right upper abdomen, and this trocar had a diameter of 1.2 cm.

The cystic duct was first dissected and clipped with a titanium clip. The common bile duct (CBD) was exposed and the junction of the cystic duct and common hepatic duct (CHD) was confirmed by a puncture, after which it was incised (2 cm in length) using a sickle-type surgical knife. The choledochofiberscope was inserted into the CBD and the gallstones are removed with gallstone forceps and scoops; if the number of gallstones was < 3 (small and free), they were able to be removed with the lithotomy net of the choledochofiberscope. Next, No. 3-6 biliary tract bougies were passed through Oddi′s muscle and a urinary catheter was inserted into the CBD for douching, after which the choledochofiberscope was re-inserted into the CBD to confirm the extraction of all gallstones. The two short arms of the T-tube were put into the CBD, the incision was closed with 1-3 stitches, and a tight knot was tied with a short thread or both the suture roots were clipped to suture the incision. The gallbladder itself was excised and removed through the umbilical incision. Finally, the long arm of the T-tube was pulled out through the incision in the midclavicular line, and a drainage tube was placed in Winslow′s foramen and pulled out through the incision in the anterior axillary line. In case of biliogenic pancreatitis, the tube (used as a drainage tube or a perfusion tube) was inserted into the omental bursa through Winslow′s foramen, after which the gastrocolic ligament was opened and the head of the other emulsion tube was placed in the tail region of the pancreas and the tail of the tube was pulled out through the other incision that had entered into the left upper abdomen for the postoperative lavage of the pancreas. According to the patient’s condition, decompression gastrostomy and nutritional jejunostomy were performed under the video laparoscope guidance.

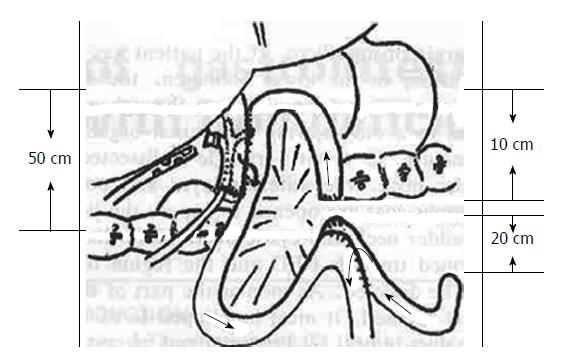

The anterior layer of the hepatoduodenal ligament was striped so that the duodenal posterior segment of the CBD was fully exposed and its inferior extremity was incised by 1 cm to remove the stones. The opposite mesangial margin of the jejunum, which was 30 cm from Treitz′s ligament, was transected by 1 cm in length. An Endo GIA 30 was inserted upwards through the two small incisions in the CBD and jejunum in order to facilitate the precolonic choledochojejunostomy (CJS) at 3 cm; the two short arms of the T-tube were put into the CHD through the small incision made beneath the anastomotic stoma. The small incision was closed with a continuous whole layer inversion suture and an interrupted sero-muscular suture. A jejunal afferent loop, at 20 cm from Treitz′s ligament, was made by a 1 cm small incision, and the efferent loop, at 50 cm from the CJS, was also made by a 1 cm small incision. An Endo GIA 30 was inserted downwards through the two small incisions of the loops for the jejunal afferent-efferent loop anastomosis at 3 cm, near the anastomotic stoma. The afferent loop was severed with an Endo GIA 30 and, simultaneously, both severed ends were closed. The small incision was closed in the above-mentioned way. Like in LCTD, the gallbladder was excised and removed, with the T-tube and drainage tube being pulled out. The LCJS procedure is diagramed in Figure 1.

The LCTD procedure was successfully applied to all 45 cases. One patient with sustained biliary leakage and one patient with sustained residual choledocholith were cured completely. The LCJS procedure was successfully applied to all 5 cases, and all the patients recovered without any complications. Usually, gastrointestinal functions were restored within 24 h after the LCTD and LCJS procedures, at which time the patients could take food. The T-tube was extracted at 2-3 wk after the LCTD or LCJS procedure if the T-tube cholangiography did not show any abnormal results.

LCTD: LCTD is suitable for patients with gallstones that are complicated with secondary choledocholith, especially for patients who have excess fat, are aged, or are complicated with diabetes (i.e. these patients usually cannot tolerate a major surgical operation), or for patients with primary or secondary choledocholith that is complicated with acute cholangitis or biliogenic pancreatitis (i.e. these patients are considered high risk and cannot tolerate major operations but are operated on under emergency conditions). Simple choledocholithotomy with T-tube drainage for primary choledocholith usually yields a poor result, since biliary stones can be easily missed and leading to high risk of recurrence; these patients should be treated with LCJS. However, in cases of severe cholangitis or acute hemorrhagic necrotic pancreatitis, if patients present with shock and diffuse peritonitis, they should be treated with routine surgical operations.

LCJS: LCJS is suitable for patients with primary choledocholith or hepatolith, but who present without stricture of the intrahepatic duct and with a CBD diameter > 1.5 cm, for patients with benign distal obstruction of CBD with co-existence of pancreatitis, cholangitis or duodentitis, or for patients with malignant obstruction and late stage cancer who are in need of palliative treatment of jaundice. However, in cases of stricture of intrahepatic duct or high-level malignant biliary obstruction, there is no indication for LCJS.

LCTD: First, the viewing incision is located in the lower margin of the umbilicus. If the patient has an operative history involving the lower abdomen, the trocars must be inserted into the abdomen through an incision so as to avoid injuring abdominal organs by a blind puncture. Second, Calot′s triangle is dissected from the gallbladder neck, after which the anterior layer and posterior layer of serous coat are opened to expose the junction of the gallbladder neck and cystic duct and blunt dissection is performed towards the CBD; the CBD region must not be dissected. As soon as the part of the cystic duct is exposed, it must be clipped so as to prevent bile duct injury. Third, the proximal end of the cystic duct is clipped with two titanium clips, the dissection of the cystic artery is not “skeletal-changed” so that the chances of creating cystic duct stump leakage and bleeding are decreased. Fourth, the CBD can be seen clearly after the lumbar region is raised. Fifth, the incision under the xiphoid is at the right midline, facilitating easy performance of LCTD. Sixth, if the gallstones have passed to the CBD during the operation, the cystic duct is first dissected and clipped with a titanium clip. For the time being, the cystic duct is not amputated and the gallbladder is not dissected either, so that traction of the gallbladder could push the hepatic margin up simultaneously and the gallbladder bed could be protected from early denuding with bleeding that would otherwise blur the operative field. Seventh, the sickle-type surgical knife blade must be used to incise the CBD, which can not only help to make the incised margins regular but also avoid injuring the posterior wall of the CBD. Eighth, lithotomy relies mainly on the common lithotomic apparatus, making the fiberscope subsidiary. When it is impossible to tie the two sutures of the incision into a tight knot, both of the suture roots should be clipped to close the incision; therefore, the operation is simple and economical, and will be easy to adopt more widely. Ninth, a thicker cystic duct is amputated by repeated clipping and cutting. Tenth, if the stones in the CBD are numerous, necessitating a longer lithotomy time, the lithotomy can be stopped and a T-tube can be put in. Three weeks after the LCTD, then, the lithotomy can be performed again with the fiberscope passing through the T-tube sinus. Eleventh, in cases of biliogenic pancreatitis, decompression gastrostomy and nutritional jejunostomy can be performed under the video laparoscope.

LCJS: First, the Endo GIA is inserted through the intermediate part of the straight muscle of the right upper abdomen, so that the LCJS could be performed easily. Second, at first the gallbladder is not excised, so that the traction of the gallbladder can help to expose the CBD more clearly. Third, the CBD is dissected until the duodenal posterior segment and inferior extremity are incised, to gain access for removal of the stones. Fourth, precolonic ansiform CJS is much easier and simpler than the postcolonic Roux-en-Y CJS. Fifth, the anastomotic stoma of CJS is 30 cm from the Treitz′s ligament, and a T-tube is inserted into the CBD through the small incision beneath the anastomotic stoma. Sixth, the jejunal afferent-efferent loop anastomosis is performed. Located above the anastomotic stoma, the afferent loop is 10 cm and the efferent loop is 50 cm; after the afferent loop is severed, the ansiform CJS is nearly changed into a Roux-en-Y CJS, and development of infection can be avoided. Seventh, near the afferent-efferent loop anastomotic stoma, the afferent loop is severed so that a cecum cannot survive, thereby helping to avoid a secondary infection.

Laparoscopic video biliary operations which we have developed and performed are not only in conformity with the biliary surgical therapeutic principle, but also easy to operate, inexpensive, practical and convenient for performance. Our results show that LCTD and LCJS have the benefits of producing minimal trauma and less suffering, while providing a quick postoperative recovery and good curative effect. Therefore, we suggest that LCTD and LCJS be popularized and more widely applied in medical practice.

Presented at the ′95 Shanghai International Laparoscopic Surgery Symposium in Shanghai China, 1995.

Original title:

S- Editor: Filipodia L- Editor: Jennifer E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Xu HB, Li HC, Xiao YQ, Zhou YP, Li WM. Clinical studies on LCTD. Endosc Sur. 1994;1:245-246. |

| 2. | Xu HB, Xiao YQ, Li HC, Peng XX, Li WM. The design and operation of laparoscopic video choledochojejunostomy. J Endosc Sur. 1994;1 suppl:286-287. |