INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation is a well-recognized complication in patients with chronic HBV infection receiving cytotoxic or immunosuppressive chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies[1-4]. Imatinib mesylate (IM) (Glivec; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland), a selective Bcr/Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), is now widely used in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and gastrointestinal stromal tumors[5,6]. Nilotinib (Tasigna; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland), a second generation TKI, was approved in 2007 for CML patients with resistance or intolerance to IM[5]. Although HBV reactivation induced by IM has been reported[7-12], nilotinib-related HBV reactivation has not been documented in current literature. We report here 2 cases of HBV reactivation in CML patients receiving IM and a novel case of nilotinib related Hepatitis B virus reactivation. Possible mechanism of TKI related HBV reactivation is discussed in this manuscript.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

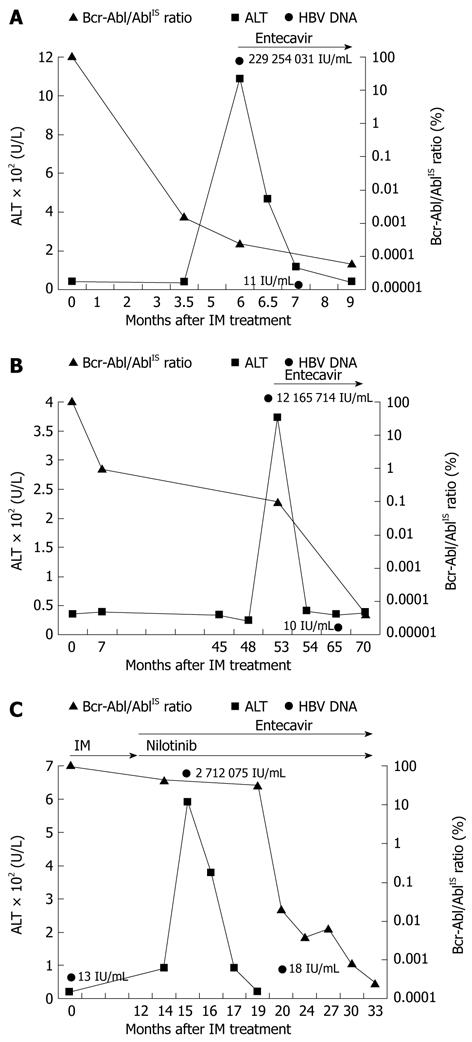

A 43-year-old man was a HBV carrier who received regular follow-ups at our institution. On December 2011, he was diagnosed with CML, which was confirmed by the presence of Philadelphia chromosome (Ph+) in cytogenetic study. He started to receive IM 400 mg once daily. The pretreatment liver panel were alanine transaminase (ALT) = 40 U/L (normal 11-40 U/L), total bilirubin = 0.8 mg/dL (normal 0.3-1.2 mg/dL), albumin = 3.5 g/dL (normal 3.5-5.5 g/dL) and prothrombin time = 11 s (normal 10-12 s). Major molecular response (MMR, < 0.1% Bcr-Abl/Abl ratio according to the international scale (IS) was achieved after 3.5 mo of IM treatment. His liver tests were within normal limits until 6 mo after IM treatment, when he started to feel easy fatigue. The patient denied usage of other medications such as acetaminophen or herbs. Laboratory investigation revealed an increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 273 U/L and an increased ALT level of 1086 U/L (Figure 1A). Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg) were positive. HBV DNA was positive at a concentration of 229 254 031 IU/mL. Results for hepatitis A immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody, hepatitis C antibody, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein Barr virus (EBV) and herpes simples 1/2 (HSV) were negative. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and immunoglobulins were within normal limits. Other biochemical studies such as bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and albumin were normal. Liver ultrasonography showed coarse liver parenchyma and normal biliary tract. Because HBV reactivation was considered, he started to receive entecavir 0.5 mg once daily. IM was not discontinued. After 1-mo treatment with entecavir, his ALT level fell to 117 IU/L and HBV DNA level was 11 IU/mL, as demonstrated in Figure 1A. Clinical symptoms resolved 6 wk later with entecavir. Complete molecular response (CMR, < 0.0001% Bcr-Abl/Abl ratio according to the IS) was achieved 9 mo after IM treatment. The clinical course of this patient is summarized in Figure 1A.

Figure 1 Clinical course of cases.

A: Case 1, showing alanine transaminase (ALT) and Bcr-Abl/AblIS ratio over time; B: Case 2, showing ALT and Bcr-Abl/AblIS ratio over time; C: Case 3, showing ALT and Bcr-Abl/AblIS ratio over time. IM: Imatinib mesylate; IS: International scale.

Case 2

A 67-year-old man with history of diabetes mellitus and HBV carrier received regular follow-ups at our hospital. He was diagnosed with CML with initial presentation of leukocytosis and thrombocytosis. He started to receive IM 400 mg once daily after bone marrow biopsy and cytogenetic study. The pretreatment liver panel were ALT = 26 U/L, total bilirubin = 1.1 mg/dL, albumin = 4.8 g/dL and prothrombin time = 12.6 s. Complete cytogenetic response (CCyR, < 1% Bcr-Abl/Abl ratio according to the IS) was achieved 7 mo after IM treatment. However, jaundice and anorexia developed 53 mo after IM treatment. Laboratory studies revealed an increased AST level of 110 U/L and an increased ALT level of 374 U/L (Figure 1B). Total bilirubin level was 2.74 mg/dL. HBsAg and HBeAg were positive. HBV DNA was positive at a concentration of 12 165 714 IU/mL. Results for hepatitis A IgM antibody, hepatitis C antibody, HSV, EBV, CMV, ANA were within normal limits. Liver ultrasonography showed no biliary tract dilatation. Entecavir 0.5 mg once daily was prescribed under the consideration of HBV reactivation. IM was not discontinued. After 1-mo treatment with entecavir, his ALT level fell to 41 IU/L, as demonstrated in Figure 1B. HBV DNA level was 10 IU/mL 12 mo after entecavir administration. Status of CMR was achieved on April, 2011. The clinical course of this patient is summarized in Figure 1B.

Case 3

A 50-year-old woman was referred to our institution on November 2009 for evaluation of leukocytosis, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. She was a HBV carrier. A diagnosis of CML was made based on the findings of proliferation of myeloid lineage cells and presence of Ph+ in bone marrow biopsy. IM 400 mg daily was used after diagnosis of CML. The pretreatment liver panel were ALT = 23 U/L, total bilirubin = 0.4 mg/dL, albumin = 4.1 g/dL and prothrombin time = 11 s. Because Bcr-Abl/Abl ratio was not significantly reduced 12 mo later with IM, treatment regimen was shifted to nilotinib 400 mg twice daily. However, 3 mo after treatment with nilotinib, the patient experienced tea-colored urine and easy fatigue. The patient denied usage of acetaminophen or herbs. Laboratory studies revealed an increased AST level of 346 U/L and an increased ALT level of 592 U/L (Figure 1C). Total-bilirubin level was 2.54 mg/dL. Coagulation profiles were normal. HBsAg was positive, whereas HBeAg was negative. Results for hepatitis A, hepatitis C, HSV, EBV, and CMV were negative. HBV DNA was positive at a concentration of 27 120 705 IU/mL. Liver ultrasonography showed normal results. Because HBV reactivation was considered, entecavir 0.5 mg once daily was prescribed. Nilotinib was not discontinued. After 2-mo treatment with entecavir, ALT level fell to 92 IU/L, as demonstrated in Figure 1C. HBV DNA was at a lower level of 18 IU/mL 6 mo after treatment with entecavir. Status of MMR was achieved 6 mo after entecavir treatment. The clinical course of this patient is summarized in Figure 1C.

DISCUSSION

HBV reactivation is characterized by an abrupt rise of HBV DNA in patients with previously inactive or resolved HBV infection during or closely after chemotherapy. The current generally accepted definition of HBV reactivation following chemotherapy is the development of hepatitis with a serum ALT greater than three times the upper limit of normal or an absolute increase of 100 IU/L, associated with a demonstrable increase in HBV DNA by at least a 10-fold[1,2]. HBV reactivation not only occurred in HBsAg-positive patients but also in HBsAg-negative patients with anti-hepatitis B core antibody positivity and/or anti-hepatitis B surface antibody positivity[1-4]. In a prospective study of 626 cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, HBV reactivation occurred in nearly 20% of them[1]. The risk factors of HBV reactivation included male gender, younger age, HBeAg seropositivity, high pre-chemotherapy HBV DNA above 3 × 105 copies/mL, use of corticosteroids and anthracyclines, and duration of chemotherapy[1,4,13]. The pathogenesis of chemotherapy-induced HBV reactivation is not clear but may involve a 2-stage process, an initial immunosuppressive stage and an immune-restoration stage[3,4]. The initial immunosuppressive stage is characterized by marked increase in serum levels of HBV DNA and HBeAg. This stage is probably related to the suppression of immune mechanism that serves to control HBV replication. The immune-restoration stage occurs after subsequent withdrawl of immunosuppressive drugs, resulting in rapid destruction of infected hepatocyte.

IM, a rationally designed TKI that blocks the ATP-binding site of Bcr/Abl, is currently recommended as the first line therapy for CML[5,6]. However, resistance to IM may occur. Nilotinib was designed to overcome IM resistance with a better efficacy and mild adverse effects[5]. Hepatotoxicity has been reported in 1%-4% of CML patients treated with IM; however, liver dysfunction may resolve with either dose reduction or discontinuation of IM[14]. In the present study, the TKIs were not discontinued after hepatic flare. Hepatic dysfunction improved in three cases after receiving entecavir, thus excluding the possibility of considering IM or nilotinib related hepatotoxicity as the cause of hepatic flare in our study. In the third case of our study, the diagnosis of HBV reactivation was established by low pretreatment HBV load and high level at the time of hepatic flare. Although the HBV load was not examined before IM treatment in the first and second cases, HBsAg and HBeAg were positive before treatment and high level of HBV load was detected at the time of hepatic flare. It is reasonable to consider HBV reactivation as the cause of hepatic flare in these two cases of our study[15-18].

The mechanism of TKI-induced HBV reactivation remains unclear due to limited case reports. In vitro studies have shown that IM can inhibit T-cell activation[19] and proliferation[20]. Nilotinib inhibited the Src-family kinase LCK and T-cell function and hampered the proliferation and function of CD8+ T lymphocytes[21,22]. It is worth noting that HBV reactivation occurred after achieving MMR in the first case (Figure 1A) and after CCyR in the second case (Figure 1B), a similar condition as that in the report of Ikeda et al[7]. In the study of Mohamad et al[23], CML patients who were in complete molecular or cytogentic response after IM treatment restored function of plasmacytoid dendritic cells, which are crucial effectors in innate immunity. Therefore, the finding of hepatic flare after complete molecular or cytogenetic responses in the first two cases may provide evidence to support the hypothesis of immune-restoration stage of HBV reactivation. Furthermore, in the third case of our study, the hepatic flare occurred 5 mo before achieving CCyR (Figure 1C). This finding suggests that nilotinib treatment might provoke a different pathway other than that of IM to achieve immune restoration. Further studies may be needed to explain this observation. An important issue that should be addressed is the preemptive therapy with nucleoside/nucleotide analogues (NAs) in patients undergoing TKI therapy. Although preemptive treatment with NAs before immunosuppressive chemotherapy is recommended in European Association for the Study of the Liver Clinical Practice guidelines[24], there is no recommendation on whether NAs should be given in patients undergoing TKI therapy due to lack of prospective studies.

In conclusion, this case report highlights the importance that HBV reactivation may occur in hematologic patients undergoing TKI therapy. Once HBV reactivation is suspected during TKI treatment, early detection of HBV load and utilization of antiviral agent are suggested to achieve better clinical outcome.