Published online Feb 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i8.1264

Revised: February 10, 2012

Accepted: March 10, 2012

Published online: February 28, 2013

AIM: To compare small bowel (SB) cleanliness and capsule endoscopy (CE) image quality following Ensure®, polyethylene glycol (PEG) and standard preparations.

METHODS: A preparation protocol for CE that is both efficacious and acceptable to patients remains elusive. Considering the physiological function of the SB as a site for the digestion and absorption of food and not as a stool reservoir, preparation consisting of a liquid, fiber-free formula ingested one day before a CE study might have an advantage over other kinds of preparations. We conducted a prospective, blind-to-preparation, two-center study that compared four types of preparations. The participants’ demographic and clinical data were collected. Gastric and SB transit times were calculated. The presence of bile in the duodenum was scored by a single, blinded-to-preparation gastroenterologist expert in CE, as was cleanliness within the proximal, middle and distal part of the SB. A four-point scale was used (grade 1 = no bile or residue, grade 4 ≥ 90% of lumen full of bile or residual material).

RESULTS: The 198 consecutive patients who were referred to CE studies due to routine medical reasons were divided into four groups. They all observed a 12-h overnight fast before undergoing CE. Throughout the 24 h preceding the fast, control group 1 (n = 45 patients) ate light unrestricted meals, control group 2 (n = 81) also ate light meals but free of fruits and vegetables, the PEG group (n = 50) ate unrestricted light meals and ingested the PEG preparation, and the Ensure group (n = 22) ingested only the Ensure formula. Preparation with Ensure improved the visualization of duodenal mucosa (a score of 1.76) by decreasing the bile content compared to preparation with PEG (a score of 2.9) (P = 0.053). Overall, as expected, there was less residue and stool in the proximal part of the SB than in the middle and distal parts in all groups. The total score of cleanliness throughout the length of the SB showed some benefit for Ensure (a score of 1.8) over control group 2 (a score of 2) (P = 0.06). The cleanliness grading of the proximal and distal parts of the SB was similar in all four groups (P = 0.6 for both). The cleanliness in the middle part of the SB in the PEG (a score of 1.8) and Ensure groups (a score of 1.7) was equally better than that of control group 2 (a score of 2.1) (P = 0.057 and P = 0.07, respectively). All 50 PEG patients had diarrhea as an anticipated side effect, compared with only one patient in the Ensure group.

CONCLUSION: Preparation with Ensure, a liquid, fiber-free formula has advantages over standard and PEG preparations, with significantly fewer side effects than PEG.

- Citation: Niv E, Ovadia B, Ron Y, Santo E, Mahajna E, Halpern Z, Fireman Z. Ensure preparation and capsule endoscopy: A two-center prospective study. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(8): 1264-1270

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i8/1264.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i8.1264

Capsule endoscopy (CE) has become a commonly applied technology for examining the small bowel (SB) mucosa[1-8]. A review of the literature revealed that there is no universally accepted protocol for bowel preparation before a CE study[9-23]. A proper preparation is one that decreases the presence of debris, food remnants, bile and stool content in the intestinal lumen and significantly increases diagnostic accuracy. Preparation by a 12-h fast and light meals one day before the procedure, as suggested by the manufacturer of the capsule, is inadequate. Investigators have prepared the bowels of their patients with different doses of purgatives [polyethylene glycol (PEG) or sodium phosphate solution] or prokinetics (erythromycin, metoclopramide, domperidone and tegaserod) and/or anti-bubble agents (simethicone)[9-23]. The main disadvantage of purgatives is that they are not well tolerated by patients. Moreover, the efficacy of both purgatives and prokinetics is controversial.

The physiologic function of the small intestine is very different from that of the colon. While the colon functions as a stool reservoir and is full of stool even during a fast, the small intestine is free of stool or any content after a 24- to 48-h fast. Since instructing patients to observe such prolonged fasting before undergoing CE is unreasonable, ingestion of a liquid, fiber-free formula instead of food during the 24 h preceding a CE examination would appear to be a more practical option for ensuring sufficient cleanliness of the small intestine as well as good patient compliance. This idea has not been investigated before.

The aim of this two-center prospective study was to compare the SB cleanliness and the quality of CE images of patients who were prepared by ingestion of Ensure (a fiber-free liquid formula) with those of patients who were assigned the PEG and two control groups.

This prospective, blind-to-preparation investigation was conducted in two Israeli medical centers, the Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center (TASMC) and the Hillel-Yaffe Medical Center (HYMC). The protocol of the study was approved by the local Helsinki committees of both centers. Consecutive patients who were referred to CE studies were asked to sign informed consent forms to participate in the study. The usual medical indications for CE referral were: (1) suspected Crohn’s disease (CD); (2) gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding of unknown origin (normal gastroscopy and colonoscopy); (3) iron deficiency anemia of unknown origin (normal gastroscopy and colonoscopy, negative celiac serology); (4) suspected malabsorption disease; (5) unexplained abdominal pain; (6) unexplained chronic diarrhea; and (7) abnormal SB findings on abdominal computerized tomogram (CT).

The exclusion criteria were: age < 18 and > 70 year, pregnancy, previous surgery involving the GI tract, previous intestinal obstruction, and refusal to participate in the study. Because of its sucrose content, diabetes mellitus was an exclusion criterion for the Ensure group only. The relevant demographic and medical data were collected, including: age, gender, the indication for a CE study, chronic diseases, medications, previous surgeries, and previous GI endoscopic examinations.

The patients were divided into four groups and they all observed a 12-h overnight fast before undergoing CE, whatever preparation protocol they followed.

The patients who were evaluated at HYMC were randomly divided into two groups. Those assigned to the PEG group were instructed to eat light meals and to ingest two liters of PEG one day before undergoing CE. Those assigned to the Ensure group were instructed to drink up to four cans of the Ensure Plus® formula ad libitum throughout 24 h, and to stop all other food/beverage intake except for water. Ensure Plus® (Abbott Laboratories) is a popular, fiber-free, polymeric-balanced formula with a caloric content of 355 kcal/can, 13 g protein, 50.1 g carbohydrates, 11.4 g fat, minerals, trace elements and vitamins.

The patients who underwent the CE study due to medical indications in TASMC during the same period of time comprised the two control groups: the control group 1 patients were instructed to eat light meals during the day before the CE, and the control group 2 patients followed a low-fiber diet (without fruits, vegetables and fiber supplements) for 2 d before CE and ate light meals one day before undergoing CE.

The CE procedure was standard in both centers. All patients ingested a PillCamTM SB 2 wireless video capsule (Given® Diagnostic Imaging System, Yokneam, Israel) with a small amount of water. An array of 8 sensors was attached to the abdominal wall, and a recorder with a battery was fastened around their waists with a belt. The patients were allowed to drink liquids two hours after ingesting the capsule and to eat a light meal four hours later. Eight hours after capsule ingestion, the recorder was disconnected and the sensors were removed. The recorded digital information was downloaded onto the computer and the images were analyzed using RAPID® software. The CE films were examined by gastroenterologists with CE expertise in both medical centers. Afterwards, a single independent expert who was unaware of the provenance of the films reviewed all films for the presence of bile and degree of cleanliness.

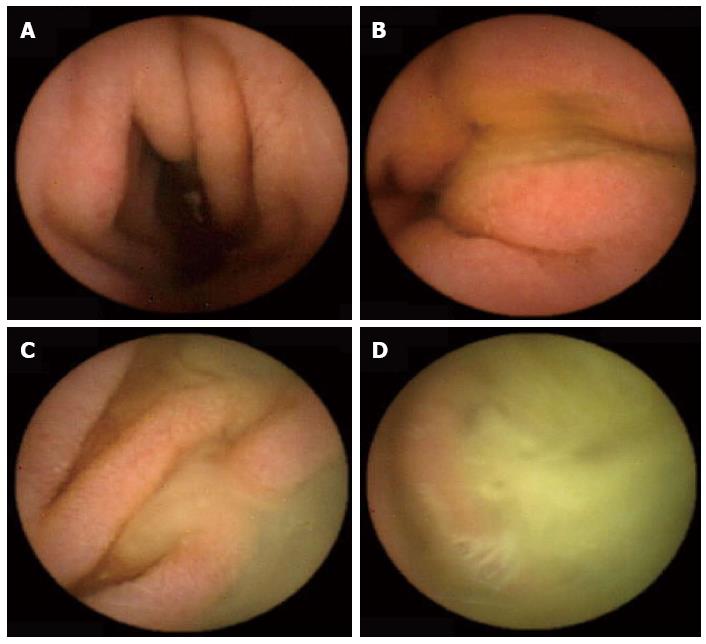

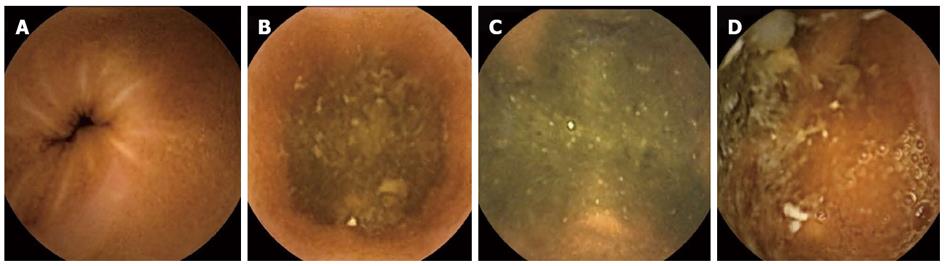

The following data were collected and analyzed from the CE studies: (1) Indications for the CE study grouped into 3 categories (suspected CD, obscure GI bleeding, others); (2) Gastric transit time as calculated from the first view of the gastric mucosa to the first image of the duodenum, expressed in minutes; (3) SB transit time as calculated from the first view of the duodenum up to the first cecal image, expressed in minutes; (4) Final diagnosis grouped into six categories (established CD, angiodysplasia, polyps, nonspecific findings, normal examination, others); (5) Cecum arrival: a CE study was defined as having been completed if the capsule reached the cecum. An abdominal X ray was performed to exclude capsule retention in cases of non-arrival; (6) The bile presence score: the presence of bile in the duodenum lumen was evaluated using a scale of 1 to 4, with 1 representing none and 4 indicating more than 90% of the lumen being full of bile (Figure 1); (7) The cleanliness score: SB cleanliness was evaluated by a 4-point scale, with 1 indicating no residual material in the lumen and 4 indicating more than 90% of the lumen having residual material (Figure 2). The SB section of the CE study was divided into three parts: proximal, middle and distal. Each part received a separate cleanliness score; (8) Extra-SB findings, i.e., the number of recorded findings in the esophagus, stomach and cecum; and (9) Follow-up, including the number of Ensure cans that were consumed, possible side effects of Ensure and PEG, level of satisfaction from preparation in PEG and Ensure groups, patient compliance with the preparation’s protocol.

Descriptive statistics are given as mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and frequency distribution for categorical variables. Comparisons between patients with different protocols of preparation with regard to demographics (age, gender), clinical parameters (indications for CE study) and CE data (final diagnosis, gastric and SB transit times, cecal arrival rate, duodenal bile score and cleanliness score) were performed using the Chi-square, Fisher’s Exact and unpaired t-tests. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was also applied if the continuous parameters did not follow a normal distribution. Pairwise comparisons were performed when the results of the overall tests were significant. The False Discovery Rate method for adjustment of significance level was used. Comparison of continuous variables between groups was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the non-parametric ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis test.

Ryan-Einot-Gabriel-Welsch pair-wise comparisons between groups were employed when the ANOVA indicated significant results. Additionally, post-hoc tests using Mann-Whitney tests with Bonferroni adjustment were performed when Kruskal-Wallis test revealed significant relations between groups and other clinical parameters. The relationships between transit time and other continuous parameters were examined by the Spearman’s correlation coefficients. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS for Windows 9.2. The statistical tests were defined as having a confidence interval of 95%. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 139 patients were screened to participate in the PEG and Ensure groups. Sixty-seven of them were excluded from the study due to the following reasons: About 13 patients had diabetes mellitus, 18 patients were younger than 18 years, 11 patients had previous intestinal surgeries, 8 patients had an urgent CE study, and 17 patients refused to participate in the study. The remaining 72 patients were divided into either the PEG (n = 50) or Ensure (n = 22) groups. Control group 1 consisted of 45 patients and control group 2 consisted of 81 patients.

Table 1 presents the demographic data of these four groups of patients. The PEG and Ensure groups were younger than both control groups. About 24%-25% of all patients in the control groups were referred to the CE study in order to rule out CD, about 60%-65% to identify a reason for obscure GI bleeding and about 11%-14% for other indications. The percentage of cases with suspected CD was higher in the PEG and Ensure groups than in the control groups. The reason for these age and referral differences between the study and control groups was related to the refusal of more of the older patients to drink PEG or Ensure. The rate of cases with non-arrival of the capsule to the cecum was not significantly different between the groups (P = 0.14). Capsule retention was excluded in all cases of incomplete studies by abdominal X-ray. One control patient and two Ensure patients had an extremely prolonged gastric transit time (> 4 h) without any anatomic reason on gastroscopy. These three patients were considered as having gastroparesis and were not included in the evaluation of the rate of non-arrival to the cecum. These patients with a gastroparesis were 25, 33 and 56 years old with no previous intestinal surgery and no diabetes mellitus. They were referred to CE study to exclude CD and celiac disease and to identify a reason for iron deficiency anemia.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | P value | |

| Overnight fast | Low fiber diet and overnight fast | PEG and overnight fast | Ensure and overnight fast | ||

| Number of patients | 45 | 81 | 50 | 22 | |

| Male/female | 21/24 | 42/39 | 27/23 | 8/14 | |

| Average age (yr) | 55.3 | 53 | 48.5 | 41.1 | 0.0138 (groups 1 and 2 vs 4) |

| Indication for CE | |||||

| Suspected CD | 11 (24.4) | 20 (24.7) | 18 (36) | 13 (59) | 0.0151 (groups 1 and 2 vs 4) |

| Obscure GI bleeding | 29 (64.4) | 50 (61.7) | 24 (48) | 6 (27.3) | 0.0124 (groups 1 and 2 vs 4) |

| Others | 5 (11.2) | 11 (13.6) | 8 (16) | 3 (13.7) | 0.9265 |

| Number of incomplete cases1 | 3 (6.7) | 5 (6.2) | 7 (14) | 3 (13.6) | 0.14 |

| +1 gastroparesis | +2 gastroparesis |

In order to provide a reliable analysis of image quality of CE studies, all cases of incomplete studies (non-arrival to cecum and gastroparesis) and those with incomplete data were excluded from the analyses in Table 2. All four resultant groups were very similar to the original groups with respect to age and indications for CE study. Overall, 107 of those 157 cases had a normal study or non-specific findings (68%). The rate of positive findings by CE was 32%. Twelve of 53 patients with suspected CD were diagnosed as having definite CD, with a yield of 23% (7.6% of all CE studies). There was an 18% rate of various extra-SB findings. Both gastric transit time and SB transit time for the four groups showed no statistical difference (P = 0.29 and P = 0.7, respectively), ranging between 29.1-40.1 min and 220.4-228 min for gastric and SB transit times, respectively.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | P value | |

| Overnight fast | Low fiber diet and overnight fast | PEG and overnight fast | Ensure and overnight fast | ||

| Number of patients | 36 | 61 | 43 | 17 | |

| Male/female | 15/21 | 34/27 | 24/19 | 5/12 | |

| Average age (yr) | 55.9 | 53 | 46.9 | 41.9 | |

| Indication for CE | |||||

| Suspected CD | 8 (22.2) | 17 (27.8) | 17 (39.5) | 10 (58.9) | |

| Obscure GI bleeding | 23 (63.9) | 37 (60.7) | 18 (41.9) | 4 (23.5) | |

| Others | 5 (13.9) | 7 (22.5) | 8 (18.6) | 3 (17.6) | |

| Final SB diagnosis | |||||

| Established CD | 2 (5.56) | 6 (9.8) | 2 (4.6) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Angioectasia | 4 (11.1) | 11 (18) | 4 (2.3) | 1 (5.9) | |

| SB Polyp | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 0 | 2 (11.8) | |

| Celiac disease | 0 | 3 (4.9) | 0 | 0 | |

| Nonspecific findings | 2 (5.56) | 7 (11.5) | 5 (11.6) | 3 (17.6) | |

| Normal study | 25 (69.4) | 29 (47.5) | 29 (67.4) | 7 (42.2) | |

| Others | 2 (5.56) | 5 (8.2) | 3 (7) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Extra-SB findings | 5 (13.9) | 16 (26.2) | 6 (14) | 4 (23.5) | |

| Mean gastric transit time (min) | 29.1 ± 35.5 | 34.9 ± 31.3 | 35.8 ± 29.8 | 40.1 ± 41 | General = 0.29; 0.075 (group 1 vs group 2); 0.08 (group 1 vs group 3) |

| Mean SB transit time(min) | 228 ± 95.4 | 220.4 ± 81.4 | 239.6 ± 84 | 222.4 ± 100.4 | General = 0.7 |

The presence of duodenal bile was similar in both control groups (Table 3). Much more bile interfered with the visualization of duodenal mucosa in the PEG group (a score of 2.9) than in the Ensure group (a score of 1.76), and the difference almost reached a level of significance (P = 0.053). Overall, as expected, there was less residue and stool in the proximal part of the SB than in the middle and distal parts in all groups. The cleanliness grading of the proximal and distal parts of the SB was similar in all four groups (P = 0.6 and P = 0.6, respectively). The scores of the middle part of the SB in the PEG and Ensure groups were lower than that of the control group 2 (P = 0.057 and P = 0.07, respectively). The total cleanliness score for the entire length of the SB showed some difference between that same control group and the Ensure group (P = 0.06), with a benefit for the latter.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | P value | |

| Overnight fast | Low fiber diet and overnight fast | PEG and overnight fast | Ensure and overnight fast | ||

| Number of patients | 36 | 61 | 43 | 17 | |

| Duodenal bile score | 1.96 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 1.76 ± 0.6 | General = 0.15; 0.053 (group 3 vs group 4) |

| Cleanliness of proximal SB | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.34 | General = 0.6 |

| Cleanliness of middle SB | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | General = 0.16; 0.057 (group 2 vs group 3); 0.07 (group 2 vs group 4) |

| Cleanliness of distal SB | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | General = 0.6 |

| Total score of clearness | 1.97 ± 0.7 | 2 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | General = 0.4; 0.06 (group 2 vs group 4) |

Patient compliance among the PEG and Ensure groups was similar (1.25 and 1.2, respectively, P = 0.7), as was subjective feeling during the preparation for CE (P = 0.163). The patients succeeded in drinking an average of two cans of Ensure, ranging from 0.25 to 4 cans per day. All 50 PEG patients had diarrhea during the day they drank it, compared to only one of the 22 patients in the Ensure group.

Our prospective, blind-to-preparation, two-center study demonstrated that a preparation by a liquid, fiber-free formula (Ensure) before a CE study has several advantages over other types of preparation. First, it improved the visualization in the duodenum by slightly decreasing the amount of bile compared with the control groups and by decreasing the amount of bile to a level that almost reached statistical significance compared with the PEG group (P = 0.053). Secondly, the total score of cleanliness throughout the length of the SB showed some benefit for the Ensure preparation over one of the control groups (P = 0.06). Finally, the cleanliness in the middle part of the SB of the patients in both the PEG and Ensure groups was better than that of one of control groups (P = 0.057 and P = 0.07, respectively). However, all patients in the PEG group had diarrhea as a side effect, compared to only one patient in the Ensure group.

Many studies have dealt with the issue of preparation before a CE study by means of different kinds of prokinetics and purgatives[9-23]. In contrast, our current study approached this problem by considering the physiological function of the SB as a place for the digestion and absorption of food and not as a reservoir for stools. As such, we expected that preparation with a liquid, fiber-free formula for one day before the CE study (followed by a 12-h overnight fast) should ensure SB cleanliness by keeping the amount of residue in the SB to a minimum. The results of our study bore out these expectations by demonstrating a positive impact of Ensure preparation on the bile score in the duodenum compared with the score for the PEG group and a total cleanliness score compared with one of the control groups. The Ensure preparation proved itself as good as PEG in terms of cleanliness in the middle part of the SB, with much less reported diarrhea. The statistical differences that showed strong trends but that rarely decreased below 0.05 to indicate significance could probably be related to the relatively small number of patients in the Ensure preparation group.

Our choice of Ensure Plus to serve as a very low-residue diet was arbitrary. We could have used any other commercially available free-fiber liquid formula and even a milkshake or soy-milkshake.

The efficacy of the PEG preparation is controversial. Some studies showed its benefit over a 12-h fast[17,18,20], while others reported no advantage[16,23]. It is obvious that preparation with 2 liters of PEG is as good as 4 liters[20]. More bile in the images of the PEG group led to poorer image quality in the duodenum than that of the Ensure group. The cleanliness in the middle part of the SB was similar to that of the Ensure group and better than that of the control groups, without there being any effect on the cleanliness of the proximal and distal parts. However, diarrhea as a common side effect was a significant disadvantage of PEG compared with Ensure and the control groups.

This study has a number of limitations. Although we succeeded in recruiting enough patients in the PEG and control groups for conducting capsule studies, the Ensure group was small. Therefore, some of our results could not reach a level of statistical significance. In addition, there were some basic differences between the groups: the PEG and ENSURE groups included younger populations with a higher percentage of CD patients. One important advantage of this study was the fact that all the scoring was done by a single blind-to-preparation expert in CE studies.

In summary, this prospective, two-center study raised, for the first time, the option of preparation for CE study with a liquid, fiber-free formula, and showed that it has some advantage over standard preparation or/and PEG, with significantly fewer side effects than PEG.

Esther Eshkol is thanked for editorial assistance.

Capsule endoscopy (CE) has become a commonly used technology for examining the small bowel (SB) mucosa. A proper preparation decreases the amount of debris, food remnants, bile and stool present in the intestinal lumen and significantly increases diagnostic accuracy. However, there is no universally accepted protocol for SB preparation before a CE study. A standard preparation by 12-h fast and light meals one day before the procedure is inadequate. Preparations with purgatives are not well tolerated by patients, and their efficacy is controversial.

Considering the physiological function of the SB as a site for the digestion and absorption of food and not as a stool reservoir, a preparation consisting of a liquid, fiber-free formula (like Ensure®) ingested one day before a CE study might have an advantage over other kinds of preparations. The aim of this two-center prospective, blind-to-preparation study was to compare the SB cleanliness and the quality of CE images of patients who were prepared by ingestion of Ensure® with those of patients who were assigned to the polyethylene glycol (PEG) group and two control groups that received standard preparation.

Preparation with Ensure® improved the visualization of duodenal mucosa by decreasing the bile content compared to preparation with PEG. The total score of cleanliness throughout the length of the SB showed some benefit for Ensure® over one of control groups. The cleanliness in the middle part of the SB in the PEG and Ensure® groups was equally better over of one of the control groups. As expected, all 50 PEG patients had diarrhea as a side effect, compared with only one patient in the Ensure group. This study presents for the first time a novel idea that preparation for undergoing CE of the SB should be completely different from the preparation for endoscopic examination of a colon and should be based on fasting and a liquid, fiber-free formula and not on purgatives.

This study results suggest that the preparation with Ensure®, a liquid, fiber-free formula has advantages over standard and PEG preparations, with significantly fewer side effects than PEG.

Capsule endoscopy: CE is a technology that uses a swallowed wireless video capsule for photographing the inside of the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine. The images are transmitted it to a belt-holded recorder. It is a well-accepted tool which provides a direct and noninvasive approach to view the entire small bowel mucosa. This technology has enriched the knowledge on small bowel pathology and revolutionized the overall management of SB diseases.

The manuscript is well-written and refers to an important issue in light of the increasing utility of the CE modality. The authors present a novel approach to a common “real life” issue and provide a new opportunity for an easy and convenient preparation.

P- Reviewer Tóth E S- Editor Lv S L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature. 2000;405:417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1994] [Cited by in RCA: 1384] [Article Influence: 55.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Scapa E, Jacob H, Lewkowicz S, Migdal M, Gat D, Gluckhovski A, Gutmann N, Fireman Z. Initial experience of wireless-capsule endoscopy for evaluating occult gastrointestinal bleeding and suspected small bowel pathology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2776-2779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Costamagna G, Shah SK, Riccioni ME, Foschia F, Mutignani M, Perri V, Vecchioli A, Brizi MG, Picciocchi A, Marano P. A prospective trial comparing small bowel radiographs and video capsule endoscopy for suspected small bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:999-1005. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Ell C, Remke S, May A, Helou L, Henrich R, Mayer G. The first prospective controlled trial comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with push enteroscopy in chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2002;34:685-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 435] [Cited by in RCA: 408] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fireman Z, Glukhovsky A, Jacob H, Lavy A, Lewkowicz S, Scapa E. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4:717-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mylonaki M, Fritscher-Ravens A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy: a comparison with push enteroscopy in patients with gastroscopy and colonoscopy negative gastrointestinal bleeding. Gut. 2003;52:1122-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rey JF, Ladas S, Alhassani A, Kuznetsov K. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE). Video capsule endoscopy: update to guidelines (May 2006). Endoscopy. 2006;38:1047-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mishkin DS, Chuttani R, Croffie J, Disario J, Liu J, Shah R, Somogyi L, Tierney W, Song LM, Petersen BT. ASGE Technology Status Evaluation Report: wireless capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:539-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Villa F, Signorelli C, Rondonotti E, de Franchis R. Preparations and prokinetics. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2006;16:211-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | de Franchis R, Avgerinos A, Barkin J, Cave D, Filoche B. ICCE consensus for bowel preparation and prokinetics. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1040-1045. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Niv Y. Efficiency of bowel preparation for capsule endoscopy examination: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1313-1317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Caddy GR, Moran L, Chong AK, Miller AM, Taylor AC, Desmond PV. The effect of erythromycin on video capsule endoscopy intestinal-transit time. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:262-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Leung WK, Chan FK, Fung SS, Wong MY, Sung JJ. Effect of oral erythromycin on gastric and small bowel transit time of capsule endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4865-4868. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Niv E, Bonger I, Barkay O, Halpern Z, Mahajna E, Depsames R, Kopelman Y, Fireman Z. Effect of erythromycin on image quality and transit time of capsule endoscopy: a two-center study. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2561-2565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Selby W. Complete small-bowel transit in patients undergoing capsule endoscopy: determining factors and improvement with metoclopramide. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:80-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fireman Z, Paz D, Kopelman Y. Capsule endoscopy: improving transit time and image view. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5863-5866. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Viazis N, Sgouros S, Papaxoinis K, Vlachogiannakos J, Bergele C, Sklavos P, Panani A, Avgerinos A. Bowel preparation increases the diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:534-538. [PubMed] |

| 18. | van Tuyl SA, den Ouden H, Stolk MF, Kuipers EJ. Optimal preparation for video capsule endoscopy: a prospective, randomized, single-blind study. Endoscopy. 2007;39:1037-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wei W, Ge ZZ, Lu H, Gao YJ, Hu YB, Xiao SD. Purgative bowel cleansing combined with simethicone improves capsule endoscopy imaging. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:77-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Park SC, Keum B, Seo YS, Kim YS, Jeen YT, Chun HJ, Um SH, Kim CD, Ryu HS. Effect of bowel preparation with polyethylene glycol on quality of capsule endoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1769-1775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Postgate A, Tekkis P, Patterson N, Fitzpatrick A, Bassett P, Fraser C. Are bowel purgatives and prokinetics useful for small-bowel capsule endoscopy? A prospective randomized controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1120-1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wi JH, Moon JS, Choi MG, Kim JO, Do JH, Ryu JK, Shim KN, Lee KJ, Jang BI, Chun HJ. Bowel preparation for capsule endoscopy: a prospective randomized multicenter study. Gut Liver. 2009;3:180-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kalantzis C, Triantafyllou K, Papadopoulos AA, Alexandrakis G, Rokkas T, Kalantzis N, Ladas SD. Effect of three bowel preparations on video-capsule endoscopy gastric and small-bowel transit time and completeness of the examination. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:1120-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |