Published online Feb 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i6.955

Revised: November 6, 2012

Accepted: November 11, 2012

Published online: February 14, 2013

Processing time: 137 Days and 23.5 Hours

Iatrogenic gastric perforation is one of the most serious complications during therapeutic endoscopy, despite significant advances in endoscopic techniques and devices. This case study evaluated the clinical efficacy and safety of the rescue endoscopic band ligation (EBL) technique in iatrogenic gastric wall perforation following the failure of primary endoclip closure. Five patients were enrolled in this study. These patients underwent emergency endoscopy following the onset of acute gastric wall perforation during endoscopic procedures. The outcome measurements were primary technical success and immediate or delayed procedure-related complications. Successful endoscopic closure using band ligation was reported in all patients, with no complication occurring. We conclude that EBL may be a feasible and safe alternate technique for the management of acute gastric perforation, especially in cases where closure is difficult with endoclips.

- Citation: Han JH, Lee TH, Jung Y, Lee SH, Kim H, Han HS, Chae H, Park SM, Youn S. Rescue endoscopic band ligation of iatrogenic gastric perforations following failed endoclip closure. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(6): 955-959

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i6/955.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i6.955

The management of gut perforation, including successful primary endoscopic repair, has been increasingly reported in endoscopic trials. Primary endoscopic therapy is now often recommended as an alternative to surgical intervention in select cases[1-3]. However, the commonly used endoclip technique for endoscopic closure has some limitations, depending on the perforation size and anatomic site. Endoscopic clip closure may be difficult for a large perforation, one with a tangential angle, and/or on a necrotic or ulcerated surface. Even when clipping is successful, dehiscence might occur due to strong wall tension. Newly developed devices have been introduced and show promise, but many of these devices are expensive, require additional equipment, and are not readily available in many countries[2,3].

Endoscopic band ligation (EBL) is commonly performed in the management of varix or Dieulafoy’s bleeding[4-6]. EBL is a safe and feasible method that can reduce procedure time and be useful in the primary repair of colonic or duodenal perforations[7-9]. Our group previously reported the use of EBL to successfully close two colonic perforations in which endoclip closure initially failed due to the presence of a large perforation and a severe tangential angle in endoscopic procedures assisted with a transparent cap[9].

In this case study, we evaluated the clinical efficacy and safety of the rescue EBL technique in iatrogenic gastric wall perforations in which primary endoclip closure failed.

Patients with acute gastric wall perforations were enrolled in this study between September 2011 and August 2012. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and the study was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

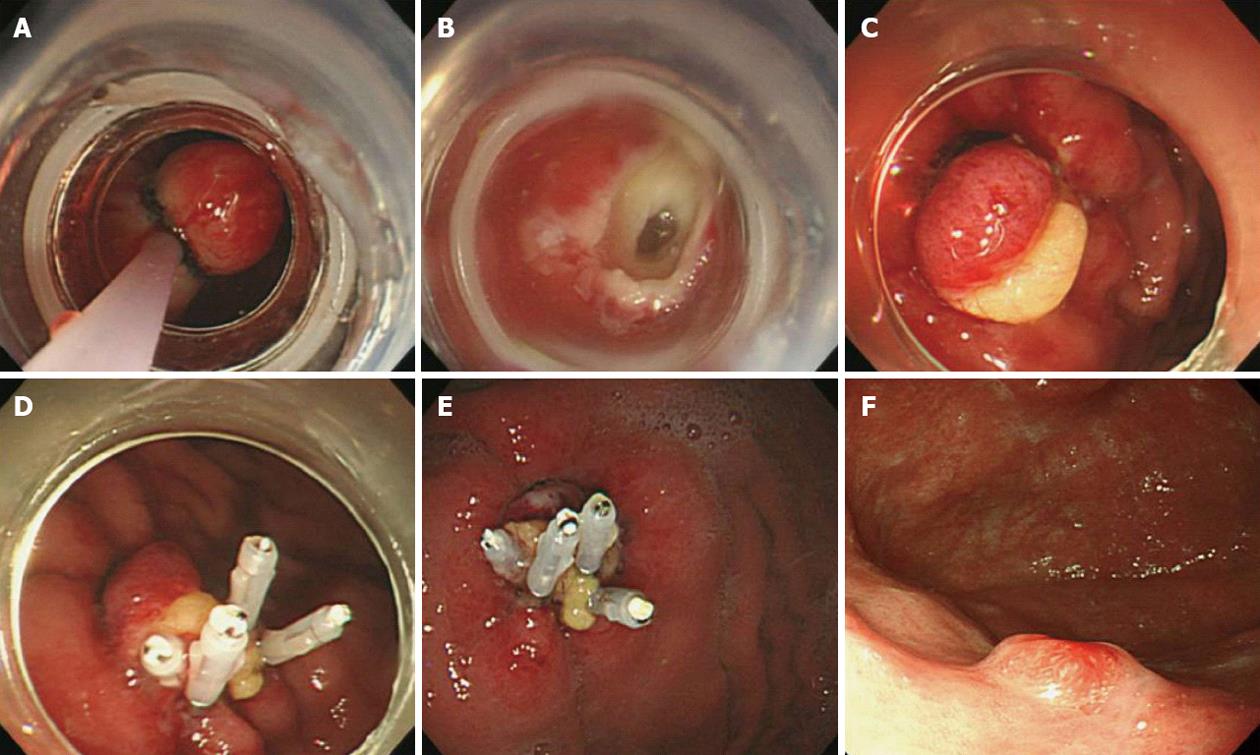

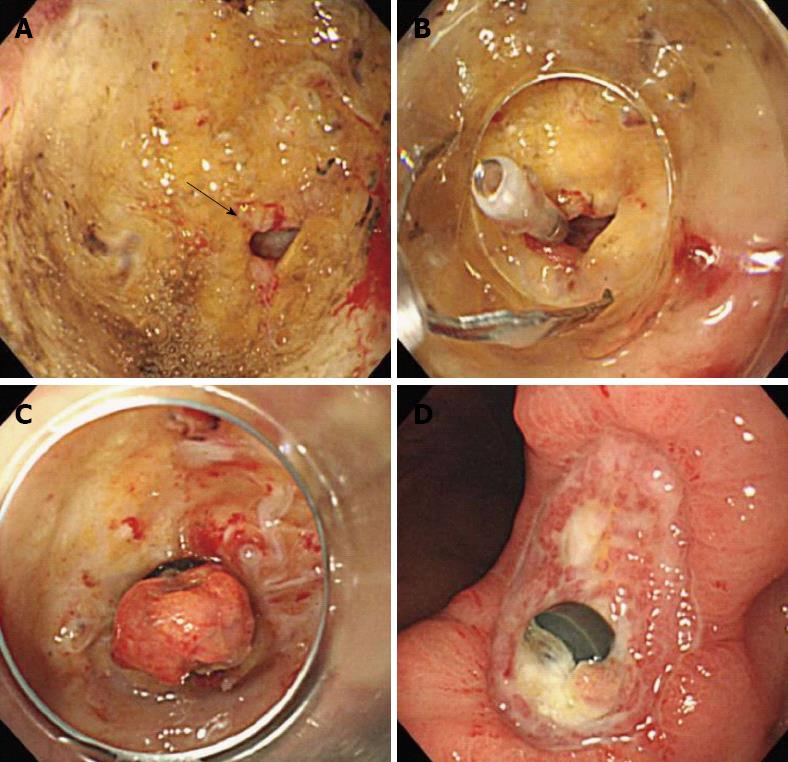

All patients underwent emergency endoscopy following the onset of acute gastric wall perforation during endoscopic procedures. Primary endoscopic closure using an endoclip (Endoclip HX-600-090L; Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was attempted initially, immediately upon recognition of the perforation. Patients in whom primary endoclip closure failed or was technically difficult subsequently underwent rescue EBL to achieve closure. After endoscopic confirmation of the perforation site, the endoscope was withdrawn and reinserted after attachment of a pneumoactive, single-band ligator (MD-48709; Akita Sumitomo Bakelite Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). The hood of the ligation device was then placed over the target lesion site. Following successful ligation of the approximate targeted edge of the perforation, additional bands or clips were used to completely close the site (Figure 1). After endoscopic closure, patients’ recovery was managed with vital sign monitoring, no oral intake, and intravenous fluid therapy with broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics and acid suppression. Early oral intake was allowed when clinical symptoms such as abdominal pain or fever resolved, appetite and bowel function returned, and laboratory test values were normalized. Surgical intervention was planned if the patient’s clinical condition deteriorated.

The outcome measurements were primary technical success and immediate or delayed procedure-related complications. All endoscopic procedures, including EBL, were performed by experienced faculty endoscopists in tertiary referral centers.

Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics of five patients who underwent rescue closure by EBL. Gut perforation rates following therapeutic endoscopic procedures were ranging from 0.9% to 1.8% in two participated units. Three patients underwent endoscopic mucosal resection with ligation (EMR-L) due to gastric adenoma (n = 2) or neuroendocrine tumor (n = 1); one patient received endoscopic submucosal dissection due to adenocarcinoma; and one patient underwent endoscopic biopsy due to a chronic gastric ulcer. The mean perforation size was 8.6 (range 5-11) mm. The primary causes of endoclip failure were difficulty in approximating the location of adjacent gastric mucosa due to wall tension and a tangential angle. In the case of ulcer base perforation occurred by biopsy (iatrogenic perforation following biopsy; Figure 2), the fibrotic ulcer base made endoscopic clipping difficult.

| No. | Age (yr)/sex | Diagnosis | Cause | Perforation location | Size (mm) | Causes of clip failure |

| 1 | 65/M | Neuroendocrine tumor | EMR-L | Fundus | 9 | Tangential angle and wall tension |

| 2 | 52/M | Gastric adenoma | EMR-L | Angle | 11 | Severe belching |

| 3 | 68/M | Gastric adenoma | EMR-L | Upper body, great curvature | 8 | Tangential angle |

| 4 | 91/F | Gastric ulcer | Biopsy | Angle | 5 | Fibrotic tissue and tension |

| 5 | 73/M | Adenocarcinoma | ESD | Antrum, great curvature | 10 | Friable mucosa |

The rescue EBL technique was performed successfully in all patients (Table 2). The mean procedure time for complete band ligation was 111.8 (range 39-334) s. Two band ligations were performed in the cases of large and ulcer base perforations. Additional endoclips were applied in four cases to achieve complete closure. No procedure-related complication or delayed dehiscence occurred following successful EBL with or without clipping. Patients resumed their normally scheduled diet an average of 4 (range 2-7) d after the procedure, and were discharged an average of 7.4 (range 4-14) d after the procedure.

| No. | Procedure time for endoclips (s) | Procedure time for EBL (s) | No. of bands | No. of clips before/after EBL | Success | Days until diet resumption/ discharge |

| 1 | 198 | 66 | 1 | 3/3 | Yes | 3/7 |

| 2 | 102 | 42 | 2 | 2/1 | Yes | 4/5 |

| 3 | 138 | 78 | 1 | 0/4 | Yes | 2/4 |

| 4 | 894 | 334 | 2 | 6/0 | Yes | 7/14 |

| 5 | 353 | 39 | 1 | 1/2 | Yes | 4/7 |

Iatrogenic gut perforations occurring during endoscopic procedures are generally managed surgically. Although surgical operation remains the gold standard treatment for intestinal perforation, the clinician’s familiarity with endoclips and their immediate availability and proper use may replace surgery for a selected group of patients with a high surgical risk. The mainstays of treatment of early perforations without systemic upset are nasogastric suction, antibiotics, bowel rest, and parenteral nutrition. This type of conservative management may be undertaken in patients with asymptomatic perforations or localized peritonitis that is expected to improve clinically without complication[1,10-14]. In presented cases, perforation was recognized immediately during procedure, and treated by endoscopic band and clipping successfully. So that, did not use nasogastic suction. However, in patients whose condition deteriorates despite conservative management or alternative endoscopic management, surgical treatment should be considered immediately.

Recent studies have reported high technical success rates for primary closure of an acute iatrogenic perforation with endoclips, newly developed devices, or a band[1,10-12]. Endoscopic repair using endoclips can be limited in large perforations or in those with tangential angles. A wide perforation is difficult to close because of slippage of the perforation edge from the clip while the clip is maneuvered across the defect to grasp the opposite edge of the perforation. Everted perforation edges also make it impossible to grasp the tissue with endoclips. Newly developed devices have recently been introduced and successfully used to close perforations[15]. These devices include through-the-scope (TTS) clips, such as the QuickClip 2 (Olympus Inc., Center Valley, PA, United States), the Resolution clip (Boston Scientific Inc., Natick, MA, United States), and the Tri-Clip and Instinct clip (Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC, United States); the over-the-scope clip (OTSC) system (Ovesco Endoscopy AG, Tubingen, Germany); and endoscopic suturing devices such as T-tags (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, United States) and the flexible Endo Stitch (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, United States). Closure of luminal perforation > 20 mm in size may be difficult. For larger gastric defects, TTS clips can be placed around the circumference of the perforation and lassoed together with a detachable plastic snare (Endo-loop; Olympus)[16]. Among the newly developed devices, OTSC was approved for the closure of perforation < 20 mm in size, and ex vivo studies shown that colon defects 10 to 30 mm in size can be closed with a single OTSC[2]. However, although some techniques have been developed to correct deficits in clip placement, they are not commonly practiced. Some of these devices may prove suitable for the closure of defects throughout the intestinal tract, but their use is limited by the endoscopist’s experience, device availability, and cost[2]. Currently, no particular technique has demonstrated proven efficacy or greater reliability than other closure modalities.

EBL was first used in 1988 to treat bleeding from esophageal varices[15]. The simplicity of the technique and low complication rates compared with sclerotherapy have contributed to its growing popularity[4]. Technically, EBL is a simple procedure, even if the targeted site must be approached tangentially or is located in the posterior wall of the proximal body. EBL has been widely used in the management of non-variceal hemorrhage from Dieulafoy’s ulcer, gastric angiodysplasia, and polypectomy-induced bleeding[4-6]. In addition, several reports have described the use of EBL in rectal and duodenal perforations during EMR[7-9]. Our group previously reported the use of EBL to successfully close two colonic perforations when endoscopic closure with endoclips initially failed[9]. Primary endoscopic repair can be difficult in some cases because the clips may not hold the tissue of large perforations together successfully, the tissue may slip in perforations with everted edges, or a fibrotic ulcer base may hinder successful manipulation. In contrast, acute perforations with no hardening can be readily closed with suction and band ligation.

Theoretically, EBL can readily approximate both edges of the perforation. Thus, complete suture to the remaining wall by additional bands or endoclips may be simple, even with a large perforation. EBL can also reduce procedure time in comparison with clipping. Immediate closure could prevent the need for surgery or the development of serious peritonitis caused by gastric content leakage. Additionally, in the case of ulcer base perforation, clipping of the fibrotic membrane is difficult due to strong wall tension, which may result in tearing or dehiscence after closure. EBL with suction could reduce such damage throughout the lesion. No dehiscence occurred after EBL in our cases. Finally, the use of additional clips to suture the perforation after EBL might not be necessary. Follow-up endoscopy has detected clip deterioration, with only the band holding the perforated mucosa tightly. Prudent banding may thus be important for successful closure, and one or more band ligations may be sufficient. However, due to the limited number of cases included in our study, we could not confirm that additional clipping is unnecessary, and we generally recommend additional clipping to maintain tight closure of the primary band.

Several factors can be identified as limitations in our study. Our case study was not comparative and included a limited number of patients, preventing us from drawing concrete conclusions. Also, this result cannot be generalized due to an experimental trial. Additionally, we did not evaluate closure dehiscence or ischemic necrosis following band ligation. Although ischemic necrosis induced by band ligation is limited to the mucosa or submucosa, further prospective studies should be conducted to examine whether the perforation risk may be lower with conventional sclerosant injection therapy, heater probe therapy, or electrocoagulation[4,17]. Secondary risks may also develop due to suction of the adjacent mesentery. None of these complications was observed in our study.In summary, EBL can be used as a rescue method to repair full-thickness perforations and may facilitate complete repair by enabling the approximation of the perforation when initial band ligation is not sufficient to achieve complete closure. EBL may be a feasible and safe alternate technique for the management of acute gastric perforation, especially in cases where closure with endoclips is difficult due to tangential angles, severe belching, or narrow space availability. To evaluate the suitability of EBL for wide clinical use, comparative controlled studies should be conducted.

P- Reviewers Cho YS, Drastich P, Farias AQ S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Lee TH, Bang BW, Jeong JI, Kim HG, Jeong S, Park SM, Lee DH, Park SH, Kim SJ. Primary endoscopic approximation suture under cap-assisted endoscopy of an ERCP-induced duodenal perforation. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2305-2310. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Baron TH, Wong Kee Song LM, Zielinski MD, Emura F, Fotoohi M, Kozarek RA. A comprehensive approach to the management of acute endoscopic perforations (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:838-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | von Renteln D, Schmidt A, Vassiliou MC, Rudolph HU, Gieselmann M, Caca K. Endoscopic closure of large colonic perforations using an over-the-scope clip: a randomized controlled porcine study. Endoscopy. 2009;41:481-486. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Van Stiegmann G, Goff JS. Endoscopic esophageal varix ligation: preliminary clinical experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:113-117. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Brown GR, Harford WV, Jones WF. Endoscopic band ligation of an actively bleeding Dieulafoy lesion. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:501-503. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Slivka A, Parsons WG, Carr-Locke DL. Endoscopic band ligation for treatment of post-polypectomy hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:230-232. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Moon SY, Park CH, Yoon SM, Chung Ys, Chung YW, Kim KO, Hahn TH, Yoo KS, Park SH, Kim JH. Repair of an endoscopic submucosal dissection-induced rectal perforation with band ligation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:160-161; discussion 161. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Fan CS, Soon MS. Repair of a polypectomy-induced duodenal perforation with a combination of hemoclip and band ligation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:203-205. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Han JH, Park S, Youn S. Endoscopic closure of colon perforation with band ligation; salvage technique after endoclip failure. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:e54-e55. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kaneko T, Akamatsu T, Shimodaira K, Ueno T, Gotoh A, Mukawa K, Nakamura N, Kiyosawa K. Nonsurgical treatment of duodenal perforation by endoscopic repair using a clipping device. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:410-413. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Katsinelos P, Paroutoglou G, Papaziogas B, Beltsis A, Dimiropoulos S, Atmatzidis K. Treatment of a duodenal perforation secondary to an endoscopic sphincterotomy with clips. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6232-6234. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Baron TH, Gostout CJ, Herman L. Hemoclip repair of a sphincterotomy-induced duodenal perforation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:566-568. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Iqbal CW, Cullinane DC, Schiller HJ, Sawyer MD, Zietlow SP, Farley DR. Surgical management and outcomes of 165 colonoscopic perforations from a single institution. Arch Surg. 2008;143:701-706; discussion 706-707. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Damore LJ, Rantis PC, Vernava AM, Longo WE. Colonoscopic perforations. Etiology, diagnosis, and management. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1308-1314. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Mangiavillano B, Viaggi P, Masci E. Endoscopic closure of acute iatrogenic perforations during diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy in the gastrointestinal tract using metallic clips: a literature review. J Dig Dis. 2010;11:12-18. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Matsuda T, Fujii T, Emura F, Kozu T, Saito Y, Ikematsu H, Saito D. Complete closure of a large defect after EMR of a lateral spreading colorectal tumor when using a two-channel colonoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:836-838. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Akahoshi K, Yoshinaga S, Fujimaru T, Harada N, Nawata H. Hypertonic saline-epinephrine injection plus endoscopic band ligation therapy for gastric Dieulafoy’s lesion. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:911-912. [PubMed] |