Published online Feb 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i6.889

Revised: November 1, 2012

Accepted: November 14, 2012

Published online: February 14, 2013

AIM: To investigate the effect of mesalazine granules on small intestinal injury induced by naproxen using capsule endoscopy (CE).

METHODS: This was a single center, non-randomized, open-label, uncontrolled pilot study, using the PillCam SB CE system with RAPID 5 software. The Lewis Index Score (LIS) for small bowel injury was investigated to evaluate the severity of mucosal injury. Arthropathy patients with at least one month history of daily naproxen use of 1000 mg and proton pump inhibitor co-therapy were screened. Patients with a minimum LIS of 135 were eligible to enter the 4-wk treatment phase of the study. During this treatment period, 3 × 1000 mg/d mesalazine granules were added to ongoing therapies of 1000 mg/d naproxen and 20 mg/d omeprazole. At the end of the 4-wk combined treatment period, a second small bowel CE was performed to re-evaluate the enteropathy according to the LIS results. The primary objective of this study was to assess the mucosal changes after 4 wk of mesalazine treatment.

RESULTS: A total of 18 patients (16 females), ranging in age from 46 to 78 years (mean age 60.3 years) were screened, all had been taking 1000 mg/d naproxen for at least one month. Eight patients were excluded from the mesalazine therapeutic phase of the study for the following reasons: the screening CE showed normal small bowel mucosa or only insignificant damages (LIS < 135) in five patients, the screening esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed gastric ulcer in one patient, capsule technical failure and incomplete CE due to poor small bowel cleanliness in two patients. Ten patients (9 female, mean age 56.2 years) whose initial LIS reached mild and moderate-to-severe enteropathy grades (between 135 and 790 and ≥ 790) entered the 4-wk therapeutic phase and a repeat CE was performed. When comparing the change in LIS from baseline to end of treatment in all patients, a marked decrease was seen (mean LIS: 1236.4 ± 821.9 vs 925.2 ± 543.4, P = 0.271). Moreover, a significant difference between pre- and post-treatment mean total LIS was detected in 7 patients who had moderate-to-severe enteropathy gradings at the inclusion CE (mean LIS: 1615 ± 672 vs 1064 ± 424, P = 0.033).

CONCLUSION: According to the small bowel CE evaluation mesalazine granules significantly attenuated mucosal injuries in patients with moderate-to-severe enteropathies induced by naproxen.

- Citation: Rácz I, Szalai M, Kovács V, Regőczi H, Kiss G, Horváth Z. Mucosal healing effect of mesalazine granules in naproxen-induced small bowel enteropathy. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(6): 889-896

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i6/889.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i6.889

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are among the most commonly prescribed medications worldwide[1,2]. The side effects of NSAIDs on the upper gastrointestinal tract are well-known, however, toxicity to the small bowel mucosa is an increasingly recognized problem and is emerging as a more prevalent site of injury than the stomach[3-7].

Advances in small bowel imaging have led to direct observation at enteroscopy and during the last decade by video capsule endoscopy (CE) allowing a full investigation of the entire small intestine[8-15].

Capsule endoscopy is capable of demonstrating NSAIDs-induced pathology in the small bowel. CE studies comparing NSAIDs users and healthy volunteers found a higher rate of lesions in the former group (55%-76% vs 7%-11%)[16-19]. The most common NSAID-induced lesions in the small bowel are mucosal breaks, reddened folds, petechial or red spots, and blood in the lumen without a visualized source of bleeding. The conclusion from these initial studies was that CE is the optimal diagnostic tool to obtain direct evidence of macroscopic injury of the small intestine, resulting from short-term (2-4 wk) administration of conventional NSAIDs.

Studies in long-term NSAID users suggest that 60%-70% have an asymptomatic enteropathy characterized by increased intestinal permeability and mild mucosal inflammation[18,20]. Occult intestinal bleeding resulting from long-term NSAID usage is an increasing clinical challenge, especially in elderly patients[21,22].

Management options for NSAID enteropathy are limited. Co-administration of proton pump inhibitors failed to prevent NSAID-induced small intestinal damage[7,8]. Cessation of NSAIDs is not tolerable for most arthropathy patients. Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors have fewer toxic effects in the small bowel[23-25]. However, due to increased cardiovascular event risk many physicians prefer to prescribe conventional NSAIDs[17]. Although a recently published short-term study showed promising results indicating that prostaglandin (PG) reduced the incidence of small-intestinal lesions induced by diclofenac sodium[19], there are no convincing long-term clinical data on the usefulness of PG co-therapy with NSAIDs. Sulfasalazine significantly reduced NSAID-provoked intestinal permeability in an experimental study[26].

Mesalazine has not yet been studied in the treatment of NSAID-induced enteropathy. However, according to the release patterns of the oral preparations of mesalazine some therapeutic efficacy was noted in Crohn’s disease, e.g., with Salofalk® tablets from the duodenum to the ileum[27-29]. Pharmacokinetic data indicate a release pattern of 5-aminosalicylate from Salofalk® granules preparation starting in the same intestinal region as that for Salofalk® tablets[30].

Thus, it would be valuable in a clinical setting to determine the therapeutic effect of mesalazine granules on NSAID-induced small intestine injury. Therefore, we investigated the effect of mesalazine granules on small intestinal injury induced by NSAIDs in an open label, uncontrolled pilot study. We assessed naproxen-induced mucosal changes using CE before and after 4 wk of treatment with 3 g mesalazine granules.

This was a single center, non-randomized, open label, uncontrolled pilot study. Entry criteria included men and women, 18-75 years of age, with at least one month history of daily naproxen use of 1000 mg for osteoarthrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or nonspecific arthritis. To avoid gastroduodenal mucosal injury, the patients were treated with a standard dose of proton pump inhibitor. A complete small bowel CE examination within 7 d of inclusion was performed to diagnose small bowel NSAID-induced enteropathy. Patients with a Lewis CE scoring index of at least 135 were eligible to enter the 4-wk treatment phase of the study. During this treatment period 3 × 1000 mg/d mesalazine granules (Salofalk® Granu-Stix®) medication was added to ongoing 1000 mg/d naproxen and 20 mg/d omeprazole therapy. At the end of the 4-wk combined therapy period, a second small bowel CE examination was performed to re-evaluate the CE enteropathy scoring index.

Patients with evidence of small bowel strictures as previously proven by barium small bowel follow through, enteroclysis or patency test capsule, or with swallowing disorders, gastroduodenal ulcer in the patient history or proven by upper endoscopy were excluded. Further exclusion criteria were a history of IBD and colon diverticulosis, mesalazine treatment within 12 wk and corticosteroid treatment within 30 d prior to baseline endoscopy. Known previous or concurrent malignancy was also an exclusion criterion.

This study was approved by the central ethics committee of the National Health Scientific Board, and all patients provided written informed consent before their enrollment in this study.

We used the PillCam SB capsule endoscopy system with RAPID 5 software (Given Imaging Ltd, Yokneam, Israel). The patients had a liquid diet on the day before the CE examination. For preparation of the small bowel, 2 L of polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution on the day before and 1 L of PEG on the morning of the CE examination were administered. The CE procedure and methodology for review of images were conducted as previously described[5,7]. Briefly, the patients were equipped with a sensor array and recorder-battery belt pack, and then swallowed a capsule, which continuously transmitted video images at 2 frames per second for 8 h, at which point, the apparatus was disconnected and the images were processed. All video images were independently analyzed by 2 reviewers per video for pathology detection. All images were saved for final comprehensive analysis.

We investigated the Lewis Index Score (LIS) for small bowel enteropathy alterations to strengthen the validity of the results[31,32]. The LIS is incorporated as an integral part of Given’s RAPID 5 version. The scoring index is based on three capsule endoscopy variables: villous appearance, ulceration, and stenosis. The changes in villous appearance and ulceration were assessed by tertiles, dividing the small bowel transit time into three equal time allotments. Villous appearance was defined as edema where villous width was equal or greater than villous height. Ulcerations were defined as mucosal breaks with white or yellow bases surrounded by red or pink collars. Ulcer size was based on the entire lesion including its surrounding collar and was measured according to the percentage of the capsule image occupied by the ulcerated lesion. The evaluation of stenosis was carried out for one entire study. The total score was the sum of the highest tertile score plus the stenosis score. The results were classified into the three categories by the final numerical score: normal or clinically insignificant change (< 135), mild change (between 135 and 790), and moderate-to-severe change (≥ 790).

The rate of successful arrival of the capsule in the cecum was assessed on the capsule endoscopic images. Gastric transit time was defined as the time taken from the first gastric image to the first duodenal image. Small bowel transit time was defined as the time from the first duodenal image to the first cecal image.

Small bowel cleanliness was graded using a 4-point scale (excellent[1] or good[2], fair[3] or poor[4]) for each tertile. Each small bowel tertile was scored separately, with the final cleansing score being the average of the sum of the three tertile cleansing scores[31].

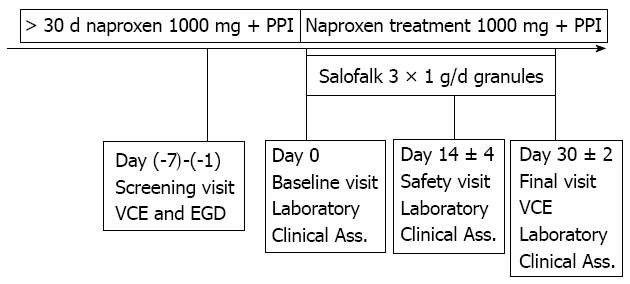

At the screening visit, patients taking 1000 mg/d naproxen and 20 mg/d omeprazole first underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to exclude active peptic ulcer. Those without active ulcer underwent the baseline CE examination. Eligible patients with LSI higher than 135 were administered 1000 mg mesalazine granules three times daily and 500 mg naproxen two times daily, and 20 mg omeprazole once daily immediately after meals for a period of 4 wk. Post-treatment CE was performed within 24 h after completion of the drug regimen (Figure 1). Patients who developed symptoms that warranted withdrawal from the study or with incomplete CE were excluded from the study and analysis.

The Lewis Index Score results, gastric transit time, small bowel transit time, cleanliness scores, hemoglobin results, results of baseline CE and the 4 wk control were compared and tested using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. In addition, paired t tests were also performed. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The effect of treatment on the presence of ulcers with a diameter of at least 3 mm was tested using the binomial sign test. McNemar tests were also performed but due to the small sample size, the binomial test was more relevant.

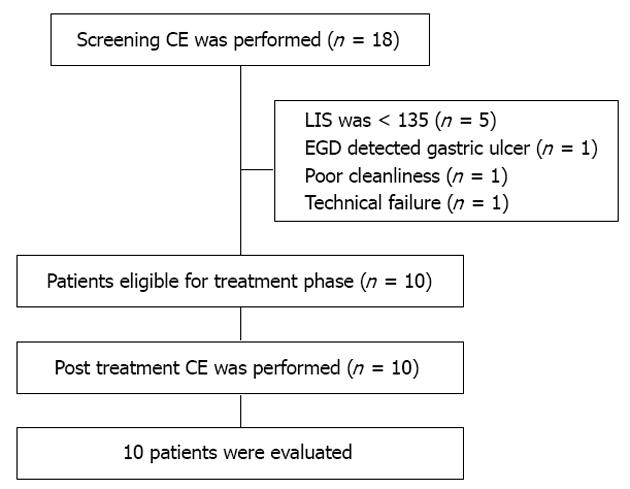

A total of 18 patients (16 females), ranging in age from 46 to 78 years (mean age 60.3 years) were screened, all had been taking 1000 mg/d naproxen for at least one month. Eight patients were excluded from the mesalazine therapeutic phase of the study for the following reasons: the screening CE showed normal small bowel mucosa or only insignificant damage (LIS < 135) in five patients, the screening EGD revealed gastric ulcer in one patient, and capsule technical failure and incomplete CE due to poor small bowel cleanliness in two patients (Figure 2). Ten patients whose initial LIS reached the mild and moderate-to-severe enteropathy grades (between 135 and 790, and ≥ 790, respectively) entered the therapeutic study phase and a second CE was carried out 4 wk later (Table 1). The CE enteropathy scores for small bowel are presented in Table 2.

| Characteristic | |

| Sex (female) | 9 |

| Age, yr (mean ± SD) | 56.2 ± 9.7 |

| Reason for NSAID therapy | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 |

| Osteoarthritis | 8 |

| Medication use | |

| Anti-hypertensive agents | 3 |

| Anti-diabetic agents | 2 |

| Low dose aspirin | NA |

| Statin | 2 |

| Subject No. | First tertile | Second tertile | Third tertile | Total LIS score |

| NSAID | ||||

| 1 | 429 | 3040 | 1404 | 3040 |

| 2 | 225 | 450 | 0 | 450 |

| 3 | 1630 | 225 | 225 | 1630 |

| 4 | 1462 | 204 | 1462 | 1462 |

| 5 | 247 | 247 | 0 | 247 |

| 6 | 1104 | 654 | 562 | 1104 |

| 7 | 1312 | 712 | 135 | 1312 |

| 8 | 361 | 0 | 0 | 361 |

| 9 | 1068 | 1068 | 225 | 1068 |

| 10 | 1690 | 393 | 135 | 1690 |

| NSAID + mesalazine | ||||

| 1 | 900 | 1208 | 1237 | 1208 |

| 2 | 1462 | 165 | 0 | 1462 |

| 3 | 247 | 0 | 247 | 247 |

| 4 | 1068 | 339 | 1012 | 1068 |

| 5 | 112 | 0 | 0 | 112 |

| 6 | 1068 | 900 | 225 | 1068 |

| 7 | 1068 | 1068 | 233 | 1068 |

| 8 | 225 | 225 | 135 | 225 |

| 9 | 1104 | 0 | 0 | 1104 |

| 10 | 1690 | 1554 | 1104 | 1690 |

At the screening CE, seven out of the ten enteropathy patients showed moderate-to-severe abnormalities according to the LIS grades (≥ 790).

In six of these seven moderate-to-severe small bowel enteropathy cases, the characteristic alterations were already seen in the first tertile, and in only three patients in the third tertile.

The average small bowel cleanliness grades were 1.3 ± 0.67 at the screening CE, and 1.4 ± 0.69 at the control CE examinations, respectively. The mean hemoglobin levels at screening and at the end of therapy were 131.1 ± 5.8 g/L and 127.1 ± 7.8 g/L, respectively (Table 3).

| Inclusion | After mesalazine gran therapy | P value | |

| Total Lewis Index Score | 1236.4 ± 821.9 | 925.2 ± 543.4 | 0.271 |

| 1st tertile | 952.8 ± 584.9 | 894.4 ± 534.3 | 0.569 |

| 2nd tertile | 699.3 ± 877.9 | 545.9 ± 580.9 | 0.649 |

| 3rd tertile | 415.3 ± 561.5 | 319.3 ± 403.3 | 0.247 |

| Ulcers with a diameter of > 3 mm, n | |||

| 1st tertile | 8 | 7 | 1.000 |

| 2nd tertile | 8 | 6 | 0.625 |

| 3rd tertile | 3 | 4 | 1.000 |

| Gastric transit time (min) | 43.8 ± 32 | 49.8 ± 35.6 | 0.470 |

| Small bowel transit time (min) | 261.9 ± 108 | 250.9 ± 93.9 | 0.470 |

| Cleanliness score | 1.3 ± 0.67 | 1.4 ± 0.69 | 0.345 |

| Hemoglobin | 131.1 ± 5.8 | 127.1 ± 7.8 | 0.103 |

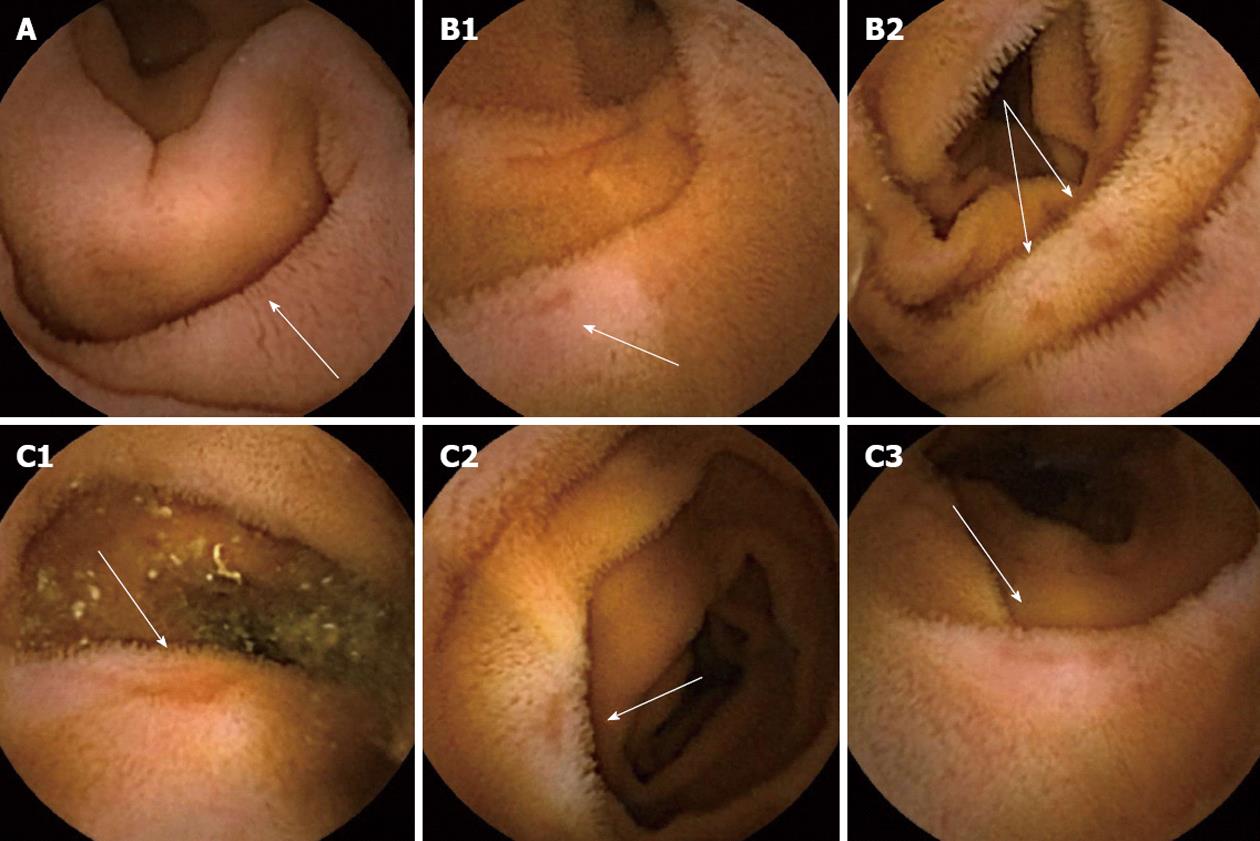

The most frequently observed NSAID-induced morphological alterations were villous edema which was present in all 10 patients at inclusion, and 19 ulcers were detected at baseline CE examinations (Figure 3). No stenosis was seen in any of the patients, either at inclusion or at the control CE examinations.

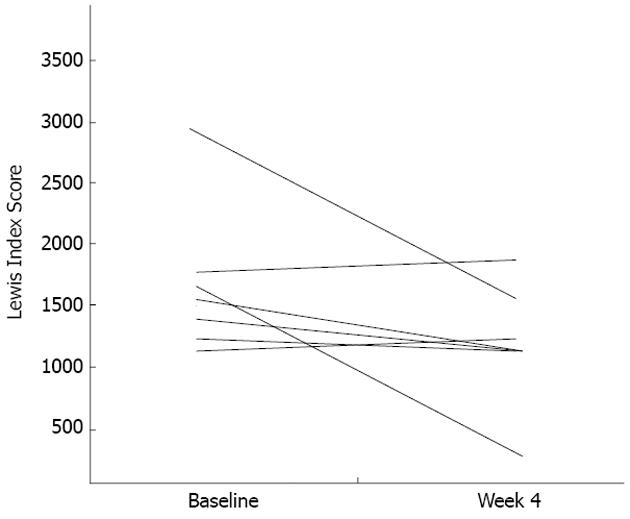

No dyspepsia or other significant abdominal symptoms were reported by the patients at any of the study visits. When comparing the LIS results assessed at inclusion and at the control CE after treatment with mesalazine granules, a marked decrease was seen (mean LIS: 1236.4 ± 821.9 vs 925.2 ± 543.4), however, the difference was not significant (P = 0.271).

In contrast, a significant difference in pre- and post-treatment LIS was detected in the seven patients who had moderate-to-severe enteropathy gradings at the inclusion CE visit (mean LIS: 1615 ± 672 vs 1064 ± 424, P = 0.033). Further analysis showed that two patients (subject number 9 and 10) in the group with moderate-to-severe NSAID-induced enteropathy at inclusion, the total LIS score was unchanged or worsened after mesalazine treatment. However, even in these two patients a decrease in LIS scores was detected either in the first or second small bowel tertile which was also seen in the other 5 cases (Figure 4).

In the present pilot study we found that mesalazine granules reduced the severity of small intestine lesions induced by the administration of naproxen, a non-selective NSAID. Patients, who received naproxen therapy with mesalazine granules showed markedly lower enteropathy scores compared with the period when naproxen was taken alone. Importantly, the co-administration of mesalazine granules significantly attenuated the mucosal damage caused by naproxen in patients with moderate-to-severe enteropathy.

NSAIDs are known to increase intestinal permeability; the severity of the mucosal injury is dose-dependently related to the potency of NSAIDs to inhibit COX-1. The increase in intestinal permeability is the most important factor which provokes NSAID-induced inflammation and injury in the small intestine[2,3].

Previous studies evaluating NSAID-associated mucosal injury have shown various ways to interpret and compare CE data. Goldstein et al[17], who compared the effects of naproxen versus celecoxib on the small bowel, simply counted the number of mucosal breaks per tertile to measure adverse drug effects. Graham et al[18] assessed small bowel mucosal injury in chronic NSAIDs users. In their study, CE lesions were scored as normal, red spots, small erosions, large erosions or ulcers. Maiden et al[16] graded diclofenac-induced lesions as category 1 (reddened folds), category 2 (denuded area), category 3 (petechia/red spot), category 4 (mucosal break), or category 5 (presence of blood without a visualized lesion).

A new score index has been developed by Gralnek et al[32] to assess mucosal changes in the small bowel detected by CE. The LIS offers objective scoring of small bowel injuries and has the potential to measure and document mucosal healing in response to therapy[33-36]. Therefore, in our study we used the LIS to assess the mucosal effect of naproxen as well as the effects of mesalazine granules therapy.

In the present pilot study we found mild and moderate-to-severe changes in the LIS in 66% of patients (10/15) who received NSAID and proton pump inhibitor therapy. These results are in a good correlation with the data from other CE studies in which NSAID-induced intestinal injury was directly evaluated. Maiden et al[16] found intestinal lesions using CE in 68% of healthy volunteers; Goldstein et al[17] reported that 55% of subjects on naproxen developed small-bowel injuries, while Fujimori et al[19] found small bowel mucosal breaks in 53% of subjects taking diclofenac. In these three studies, CE examinations were performed in healthy volunteers after two wk of NSAID medication. Graham et al[18] performed small bowel CE in chronic NSAID users with at least 3 mo history of daily NSAIDs for rheumatologic diseases. Small bowel injury was seen in 71% of these patients. Similar to this study we also recruited patients taking NSAIDs chronically which better reflects the real life situation in the small bowel compared to short-term NSAID exposure.

We analyzed the LIS results for NSAID-induced mucosal changes according to the small bowel tertiles. This analysis revealed that mucosal injuries tended to decrease in severity in the distal part of the small bowel. This result is inconsistent with a previous report in which chronic low dose aspirin-associated ulcers were observed mainly in the distal part of the small bowel[36]. However, there are no other available data regarding the topical distribution of NSAID-induced small bowel changes.

Management of NSAID-induced enteropathy is an unsolved problem. Moreover, the clinical significance of small bowel lesions is also a challenge. Proton-pump-inhibitors have been proved to be ineffective for the prevention of NSAID-induced injury[16-19]. Celecoxib, a selective COX-2 inhibitor effectively decreased the number of mucosal breaks and the percentage of subjects with at least one mucosal break[17]. Nevertheless, due to the risk of cardiovascular events, the use of COX-2 inhibitors is limited. In a recent pilot study co-administration of misoprostol was effective in preventing small bowel injury induced by NSAID medication in healthy volunteers[19]. Although the results of this short-term trial are promising, the clinical outcome of misoprostol therapy in typical chronic NSAIDs users is still an open question.

The role of sulfasalazine has been evaluated in 40 patients with rheumatoid arthritis on NSAIDs[26]. After 3-9 mo treatment, sulfasalazine (1.5-3.5 g/d) significantly reduced intestinal permeability, as measured by 111In-labelled leucocytes.

Mesalazine has not yet been studied for the prevention or treatment of NSAID-induced enteropathy. Based on the hypothesis that mesalazine granules may have some therapeutic effect against NSAID-induced small bowel injury we designed a short-term therapeutic trial instead of a preventive trial. The primary objective of our pilot study was to assess the mucosal changes according to the LIS results detected by CE after 4 wk of treatment with mesalazine granules in patients receiving naproxen therapy. To avoid to inclusion of patients with clinically insignificant small bowel injuries, only patients with a LIS > 135 were recruited into the mesalazine granules therapeutic phase. When comparing the pre- and post-therapeutic LIS results in all 10 patients, a marked but not significant improvement in NSAID-induced enteropathy was observed. However, in the analysis of the 7 patients with moderate-to-severe initial enteropathy a significant improvement in the LIS was seen after treatment with mesalazine granules. These results demonstrate that patients whose initial enteropathy was more advanced benefited most from mesalazine treatment. Importantly, the improvement in LIS results was detected mainly in the first and second small bowel tertiles indicating that the mesalazine granules were effective even in the upper part of the small intestine. Although this is in contrast to the normal release profile of mesalazine, this may be due to the concomitant therapy with omeprazole.

According to the patient diaries and despite continuous NSAID treatment, our patients did not have dyspeptic symptoms or any other adverse effects. Significant anemia was not detected, either at inclusion or at the controls during the treatment phase. Ulcer-like clinical symptoms and dyspepsia are driven most probably by the gastroduodenal effect of NSAIDs which can be abolished or prevented by omeprazole co-therapy.

This is the first study to demonstrate using CE that mesalazine granules can reduce NSAID-induced macroscopic damage throughout the small intestine. This was also the first study to use the LIS system to evaluate the therapeutic effect of mesalazine granules on NSAID-induced small bowel injury. However, the trial has some inherent limitations. First, our study included only a small number of patients. Second, there was no parallel control group included to test the mucosal effect of the NSAID without mesalazine treatment. Third, this study was an open-label trial, which has a potential bias against neutrality.

Consequently, further studies are necessary to confirm the beneficial effect of mesalazine granules detected in the present pilot study.

We thank Dr. Ralph Müller for help during our clinical research and also for the advices during the manuscript preparation.

The side effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) on the upper gastrointestinal tract are well-known, however, toxicity to the small bowel mucosa is an increasingly recognized problem and is emerging as a more prevalent site of injury than the stomach. Capsule endoscopy (CE) is capable of demonstrating NSAID-induced pathology in the small bowel. CE is the optimal diagnostic tool to obtain direct evidence of macroscopic injury of the small intestine, resulting from short-term (2-4 wk) administration of conventional NSAIDs. Studies in long-term NSAID users suggest that 60%-70% have an asymptomatic enteropathy characterized by increased intestinal permeability and mild mucosal inflammation. Management options for NSAID-induced enteropathy are limited. Mesalazine has not yet been studied in the treatment of NSAID-induced enteropathy. In this article the authors investigated the effect of mesalazine granules on small intestinal injury induced by naproxen in an open label, uncontrolled pilot study. The authors assessed naproxen-induced mucosal changes using CE before and after 4 wk of treatment with 3 g mesalazine granules.

Entry criteria included men and women, 18-75 years of age, with at least one month history of daily naproxen use of 1000 mg for osteoarthrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or nonspecific arthritis. To avoid gastroduodenal mucosal injury, the patients were treated with a standard dose of proton pump inhibitor. A complete small bowel CE examination within 7 d of inclusion was performed to diagnose small bowel NSAID-induced enteropathy. Patients with a Lewis capsule endoscopy scoring index of at least 135 were eligible to enter the 4-wk treatment phase of the study. During this treatment period, 3 × 1000 mg/d mesalazine granules (Salofalk® Granu-Stix®) medication was added to ongoing 1000 mg/d naproxen and 20 mg/d omeprazole therapy. At the end of the 4-wk combined therapy period, a second small bowel CE examination was performed to re-evaluate the capsule endoscopy enteropathy scoring index.

The authors found that mesalazine granules reduced the severity of small intestine lesions induced by the administration of naproxen, a non-selective NSAID. Patients, who received naproxen therapy with mesalazine granules showed markedly lower enteropathy scores compared with the period when naproxen was administered alone. Importantly, the co-administration of mesalazine granules significantly attenuated the mucosal damage caused by naproxen in patients with moderate-to-severe enteropathy.

This study offers a better understanding of the NSAID-induced enteropathy changes evaluated by the Lewis Index Score (LIS). The results demonstrated that patients whose initial naproxen-induced enteropathy was the most advanced benefited most from treatment with mesalazine granules.

The LIS was used to investigate small bowel enteropathy alterations to strengthen the validity of the results. The LIS is incorporated as an integral part of Given’s RAPID 5 version. The scoring index is based on three capsule endoscopy variables: villous appearance, ulceration, and stenosis. The changes in villous appearance and ulceration were assessed by tertiles, dividing the small bowel transit time into three equal time allotments. The results were classified into the three categories by the final numerical score: normal or clinically insignificant change (< 135), mild change (between 135 and 790), and moderate-to-severe change (≥ 790).

Management of NSAID enteropathy is an unsolved problem. The authors present a pilot study in a group of patients with NSAID macroscopic lesions found in small intestine. The authors evaluate the effect of treatment by mesalazine in this group of patients using CE and an objective score (LIS). The result has limited statistical power due to the scarce number of patients included in the study. Nevertheless, the figures are promising and, as said by the authors, open an investigational field on NSAID side effects prevention/treatment, needing further investigation.

P- Reviewers Koulaouzidis A, Bordas JM S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Fries JF, Williams CA, Bloch DA, Michel BA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastropathy: incidence and risk factor models. Am J Med. 1991;91:213-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Allison MC, Howatson AG, Torrance CJ, Lee FD, Russell RI. Gastrointestinal damage associated with the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:749-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 718] [Cited by in RCA: 674] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fortun PJ, Hawkey CJ. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the small intestine. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21:169-175. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Fujimori S, Seo T, Gudis K, Tanaka S, Mitsui K, Kobayashi T, Ehara A, Yonezawa M, Tatsuguchi A, Sakamoto C. Diagnosis and treatment of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding using combined capsule endoscopy and double balloon endoscopy: 1-year follow-up study. Endoscopy. 2007;39:1053-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hawkey CJ. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastropathy. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:521-535. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Langman MJ, Morgan L, Worrall A. Use of anti-inflammatory drugs by patients admitted with small or large bowel perforations and haemorrhage. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;290:347-349. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Manetas M, O’Loughlin C, Kelemen K, Barkin JS. Multiple small-bowel diaphragms: a cause of obscure GI bleeding diagnosed by capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:848-851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature. 2000;405:417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1994] [Cited by in RCA: 1384] [Article Influence: 55.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Yamamoto H, Sekine Y, Sato Y, Higashizawa T, Miyata T, Iino S, Ido K, Sugano K. Total enteroscopy with a nonsurgical steerable double-balloon method. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:216-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 896] [Cited by in RCA: 861] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lewis BS. Expanding role of capsule endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4137-4141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lucendo AJ, Guagnozzi D. Small bowel video capsule endoscopy in Crohn’s disease: What have we learned in the last ten years? World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:23-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Eliakim R, Fischer D, Suissa A, Yassin K, Katz D, Guttman N, Migdal M. Wireless capsule video endoscopy is a superior diagnostic tool in comparison to barium follow-through and computerized tomography in patients with suspected Crohn’s disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:363-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Costamagna G, Shah SK, Riccioni ME, Foschia F, Mutignani M, Perri V, Vecchioli A, Brizi MG, Picciocchi A, Marano P. A prospective trial comparing small bowel radiographs and video capsule endoscopy for suspected small bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:999-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 565] [Cited by in RCA: 517] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Friedman S. Comparison of capsule endoscopy to other modalities in small bowel. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2004;14:51-60. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Chan FK, Graham DY. Review article: prevention of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastrointestinal complications--review and recommendations based on risk assessment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:1051-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Maiden L, Thjodleifsson B, Seigal A, Bjarnason II, Scott D, Birgisson S, Bjarnason I. Long-term effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclooxygenase-2 selective agents on the small bowel: a cross-sectional capsule enteroscopy study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1040-1045. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Goldstein JL, Eisen GM, Lewis B, Gralnek IM, Zlotnick S, Fort JG. Video capsule endoscopy to prospectively assess small bowel injury with celecoxib, naproxen plus omeprazole, and placebo. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:133-141. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Graham DY, Opekun AR, Willingham FF, Qureshi WA. Visible small-intestinal mucosal injury in chronic NSAID users. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:55-59. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Fujimori S, Seo T, Gudis K, Ehara A, Kobayashi T, Mitsui K, Yonezawa M, Tanaka S, Tatsuguchi A, Sakamoto C. Prevention of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced small-intestinal injury by prostaglandin: a pilot randomized controlled trial evaluated by capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1339-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sigthorsson G, Tibble J, Hayllar J, Menzies I, Macpherson A, Moots R, Scott D, Gumpel MJ, Bjarnason I. Intestinal permeability and inflammation in patients on NSAIDs. Gut. 1998;43:506-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Smalley WE, Ray WA, Daugherty JR, Griffin MR. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the incidence of hospitalizations for peptic ulcer disease in elderly persons. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:539-545. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Laine L, Connors LG, Reicin A, Hawkey CJ, Burgos-Vargas R, Schnitzer TJ, Yu Q, Bombardier C. Serious lower gastrointestinal clinical events with nonselective NSAID or coxib use. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:288-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sigthorsson G, Crane R, Simon T, Hoover M, Quan H, Bolognese J, Bjarnason I. COX-2 inhibition with rofecoxib does not increase intestinal permeability in healthy subjects: a double blind crossover study comparing rofecoxib with placebo and indomethacin. Gut. 2000;47:527-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hawkey CJ, Ell C, Simon B, Albert J, Keuchel M, McAlindon M, Fortun P, Schumann S, Bolten W, Shonde A. Less small-bowel injury with lumiracoxib compared with naproxen plus omeprazole. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:536-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Goldstein JL, Eisen GM, Lewis B, Gralnek IM, Aisenberg J, Bhadra P, Berger MF. Small bowel mucosal injury is reduced in healthy subjects treated with celecoxib compared with ibuprofen plus omeprazole, as assessed by video capsule endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1211-1222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bjarnason I, Hopkinson N, Zanelli G, Prouse P, Smethurst P, Gumpel JM, Levi AJ. Treatment of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug induced enteropathy. Gut. 1990;31:777-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gross V, Andus T, Fischbach W, Weber A, Gierend M, Hartmann F, Schölmerich J. Comparison between high dose 5-aminosalicylic acid and 6-methylprednisolone in active Crohn’s ileocolitis. A multicenter randomized double-blind study. German 5-ASA Study Group. Z Gastroenterol. 1995;33:581-584. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Schreiber S, Howaldt S, Raedler A. Oral 4-aminosalicylic acid versus 5-aminosalicylic acid slow release tablets. Double blind, controlled pilot study in the maintenance treatment of Crohn’s ileocolitis. Gut. 1994;35:1081-1085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tromm A, Bunganič I, Tomsová E, Tulassay Z, Lukáš M, Kykal J, Bátovský M, Fixa B, Gabalec L, Safadi R. Budesonide 9 mg is at least as effective as mesalamine 4.5 g in patients with mildly to moderately active Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:425-434.e1; quiz e13-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Brunner M, Greinwald R, Kletter K, Kvaternik H, Corrado ME, Eichler HG, Müller M. Gastrointestinal transit and release of 5-aminosalicylic acid from 153Sm-labelled mesalazine pellets vs. tablets in male healthy volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1163-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Koulaouzidis A, Douglas S, Plevris JN. Lewis score correlates more closely with fecal calprotectin than Capsule Endoscopy Crohn’s Disease Activity Index. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:987-993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Gralnek IM, Defranchis R, Seidman E, Leighton JA, Legnani P, Lewis BS. Development of a capsule endoscopy scoring index for small bowel mucosal inflammatory change. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:146-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Koulaouzidis A, Douglas S, Plevris JN. Blue mode does not offer any benefit over white light when calculating Lewis score in small-bowel capsule endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:33-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rácz I. Is low-dose aspirin really harmful to the small bowel? Digestion. 2009;79:42-43. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Endo H, Hosono K, Inamori M, Kato S, Nozaki Y, Yoneda K, Akiyama T, Fujita K, Takahashi H, Yoneda M. Incidence of small bowel injury induced by low-dose aspirin: a crossover study using capsule endoscopy in healthy volunteers. Digestion. 2009;79:44-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Endo H, Hosono K, Higurashi T, Sakai E, Iida H, Sakamoto Y, Fujita K, Takahashi H, Koide T, Yoneda M. Quantitative analysis of low-dose aspirin-associated small bowel injury using a capsule endoscopy scoring index. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:56-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |