Published online Feb 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i5.715

Revised: September 11, 2012

Accepted: September 28, 2012

Published online: February 7, 2013

Processing time: 192 Days and 6.7 Hours

AIM: This study analyzed clinical long-term outcomes after endoscopic therapy, including the incidence and treatment of relapse.

METHODS: This study included 19 consecutive patients (12 male, 7 female, median age 54 years) with obstructive chronic pancreatitis who were admitted to the 2nd Medical Department of the Technical University of Munich. All patients presented severe chronic pancreatitis (stage III°) according to the Cambridge classification. The majority of the patients suffered intermittent pain attacks. 6 of 19 patients had strictures of the pancreatic duct; 13 of 19 patients had strictures and stones. The first endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP) included an endoscopic sphincterotomy, dilatation of the pancreatic duct, and stent placement. The first control ERP was performed 4 wk after the initial intervention, and the subsequent control ERP was performed after 3 mo to re-evaluate the clinical and morphological conditions. Clinical follow-up was performed annually to document the course of pain and the management of relapse. The course of pain was assessed by a pain scale from 0 to 10. The date and choice of the therapeutic procedure were documented in case of relapse.

RESULTS: Initial endoscopic intervention was successfully completed in 17 of 19 patients. All 17 patients reported partial or complete pain relief after endoscopic intervention. Endoscopic therapy failed in 2 patients. Both patients were excluded from further analysis. One failed patient underwent surgery, and the other patient was treated conservatively with pain medication. Seventeen of 19 patients were followed after the successful completion of endoscopic stent therapy. Three of 17 patients were lost to follow-up. One patient was not available for interviews after the 1st year of follow-up. Two patients died during the 3rd year of follow-up. In both patients chronic pancreatitis was excluded as the cause of death. One patient died of myocardial infarction, and one patient succumbed to pneumonia. All three patients were excluded from follow-up analysis. Follow-up was successfully completed in 14 of 17 patients. 4 patients at time point 3, 2 patients at time point 4, 3 patients at time point 5 and 2 patients at time point 6 and time point 7 used continuous pain medication after endoscopic therapy. No relapse occurred in 57% (8/14) of patients. All 8 patients exhibited significantly reduced or no pain complaints during the 5-year follow-up. Seven of 8 patients were completely pain free 5 years after endoscopic therapy. Only 1 patient reported continuous moderate pain. In contrast, 7 relapses occurred in 6 of the 14 patients. Two relapses were observed during the 1st year, 2 relapses occurred during the 2nd year, one relapse was observed during the 3rd year, one relapse occurred during the 4th year, and one relapse occurred during the 5th follow-up year. Four of these six patients received conservative treatment with endoscopic therapy or analgesics. Relapse was conservatively treated using repeated stent therapy in 2 patients. Analgesic treatment was successful in the other 2 patients.

CONCLUSION: 57% of patients exhibited long-term benefits after endoscopic therapy. Therefore, endoscopic therapy should be the treatment of choice in patients being inoperable or refusing surgical treatment.

- Citation: Weber A, Schneider J, Neu B, Meining A, Born P, von Delius S, Bajbouj M, Schmid RM, Algül H, Prinz C. Endoscopic stent therapy in patients with chronic pancreatitis: A 5-year follow-up study. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(5): 715-720

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i5/715.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i5.715

The optimal treatment for chronic pancreatitis is controversial among surgeons and endoscopists. Endoscopic drainage procedures include optional sphincterotomy, stricture dilation, stone removal, and the insertion of a plastic stent. The surgical approaches are classified as drainage and resective procedures. Resective procedures, such as the duodenum-preserving head resections of Beger and Frey, provide good pain control and preserve pancreatic function[1]. Drainage procedures, such as the pancreaticojejunostomy, are comparable to endoscopic treatments because both of these procedures are based on the same pathophysiological idea. The primary goal is to restore pancreatic drainage to lower the pressure within the pancreatic duct and relieve pain[2-4]. Cahen et al[5] compared the clinical outcome of patients with endoscopic treatment and patients undergoing pancreaticojejunostomy in a prospective randomized trial. The authors concluded that surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct was more effective than endoscopic treatment. However, some patients are inoperable or refuse surgical treatment. Endoscopic therapy offers as an alternative approach for these patients. We reported previously that endoscopic therapy provided good immediate and short-term benefits to patients with obstructive chronic pancreatitis[6]. The current manuscript provides additional data from a 5-year follow-up to analyze clinical long-term outcomes after the successful completion of endoscopic therapy, including the incidence and treatment of relapse.

This section is similar to our previously published 2-year follow-up study[6]. All patients presented severe chronic pancreatitis (stage III°) according to the Cambridge classification[7] at the time of sphincterotomy and the majority of the patients (11/19) suffered intermittent pain attacks according to the Amman Score[8]. About 6 of 19 patients had strictures of the pancreatic duct; 13 of 19 patients had strictures and stones.

The first control endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP) was performed 4 wk after stenting, and the subsequent control ERP was performed after 3 mo to re-evaluate the clinical and morphological conditions. Either a new stent was inserted, or stent therapy was terminated depending on the clinical and morphological conditions.

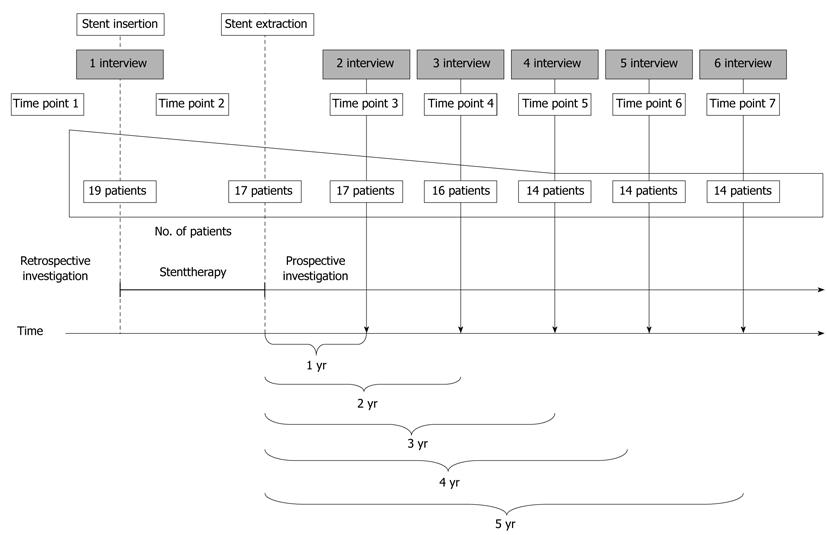

The long-term effects of stent therapy were analyzed after the successful completion of stent therapy. A short overview of the study protocol is illustrated in Figure 1. Follow-up analyses were conducted from 2004 to 2009. The ethical committee stated that the patient’s choice of treatment was protected. Clinical parameters, such as pain and the intake of pain medication, were documented: (1) Prior to endoscopic therapy (time point 1); (2) During endoscopic therapy (time point 2); and (3) Annually during the 5-year follow-up period (time points 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7).

Interviews: The first interview was a two-part session that was conducted during stent therapy. This interview analyzed the technical success of ERP and compared the pain situation prior to and after initial stent therapy (Figure 1). The first session was conducted prior to the first stent implantation (time point 1), and the second session was conducted after the initial stent implantation (time point 2). All 17 patients were interviewed annually during the follow-up period. The interviews primarily evaluated the course of pain. The patients graded their pain on a pain scale from 0 to 10: 0 was no pain, 1-2 slight pain, 3-4 moderate pain, 5-6 strong pain, 7-8 very strong pain, and 9-10 extreme pain. The date and choice of the therapeutic procedure (e.g., conservative pain management, endoscopic or surgical treatment) were documented for instances of relapse.

Statistical analysis was not performed. The evaluation of pain was carried out using a pain score in absolute numbers.

This section is similar to our previously published 2-year follow-up study[6].

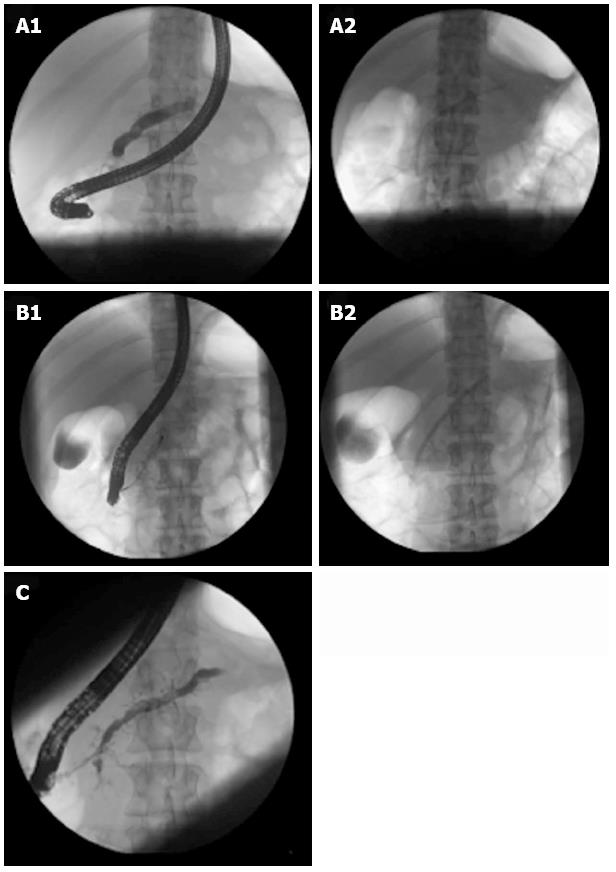

Nineteen patients with chronic obstructive pancreatitis underwent endoscopic stent therapy. Figure 2 is an illustration of a representative ERP procedure. ERP failed in 2 patients in which cannulation or permanent stent therapy was not achieved. One failed patient underwent surgery, and the other patient was treated conservatively with pain medication. We excluded these 2 patients from follow-up analyses. Endoscopic stent therapy was successfully completed in 17 of 19 patients. All 17 patients reported partial or complete pain relief.

The clinical courses of 17 patients were evaluated after the successful completion of stent therapy. Three of the 17 patients were lost during follow-up. One patient was not available for interviews after the 1st year of follow-up (Figure 1). Two patients died during the 3rd year of follow-up, and chronic pancreatitis was excluded as the cause of death. One patient died of myocardial infarction, and one patient succumbed to pneumonia.

Patients consumed the following pain medications during the 5-year follow-up period: paracetamol (500-1000 mg/d), diclofenac (50-100 mg/d), metamizol (500-1000 mg/d) and/or tramadol (100-300 mg/d). 4 patients at time point 3, 2 patients at time point 4, 3 patients at time point 5 and 2 patients at time point 6 and time point 7 used continuous pain medication after endoscopic therapy.

Seven relapses occurred in 6 of the 14 patients (43%). One patient developed 2 relapses during the 1st and 3rd follow-up years. Two relapses were observed during the 1st year, 2 relapses occurred during the 2nd year, one relapse was observed during the 3rd year, one relapse occurred during the 4th year, and one relapse occurred during the 5th follow-up year.

Four of these six patients received conservative treatment with endoscopic therapy or analgesics. Two patients were successfully treated with endoscopic therapy. Two patients achieved pain improvement with analgesic therapy. Only 2 of the 6 patients required surgery.

In contrast, 57% (8/14) of the patients without relapse reported significantly reduced pain or no complaints 5 years after stent extraction. Seven of these patients were completely pain free. Only 1 patient reported continuous moderate pain.

Several reviews[9-14] suggest that the majority of physicians consider pancreatic duct stenting a safe and effective therapy for patients with chronic abdominal pain due to chronic pancreatitis. The primary goal of endoscopic therapy is pain relief. Approximately half of the patients in the current study exhibited clinical long-term benefits. Most patients (57%, 8/14) exhibited significantly reduced pain or no pain complaints 5 years after stent extraction. Endoscopic treatment was an effective alternative to surgery in instances of relapse. Four of six re-treated patients received conservative treatment with endoscopic or analgesic therapy. Only two of these patients required surgery.

The impact of smoking and alcohol on pain development was not evaluated in this study. However, smoking and alcohol are associated with more a progressive disease course[15-20]. Therefore, the cessation of smoking and alcohol consumption was recommended to all patients in the study. No relationship between the duration of stenting and the occurrence of relapse was observed. However, the small number of patients in this study prohibits valid conclusions. Further studies with a larger number of patients are required.

Surgical procedures seem to be superior to endoscopic therapy. Díte et al[21] compared the clinical benefit of endoscopic and surgical therapies in a randomized prospective study. The study included 140 patients with chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopic therapy was performed in 64 patients, and 76 patients underwent surgery. Both therapeutic approaches produced excellent results in initial pain relief (92.1% and 92.2%, respectively). The number of patients with partial or complete pain relief at the 5-year follow-up in the stent group decreased from 92.2% to 65.1%, but 86.2% of patients with surgical procedures reported reduced or no pain. These authors concluded that surgery was superior to endoscopic therapy for long-term pain reduction in patients with painful obstructive chronic pancreatitis. However, 80% of the surgeries were resection procedures. Resection procedures are based on a different pathophysiological concept than endoscopic or surgical drainage. Therefore, these procedures are only comparable to a limited degree. The prospective randomized study of Cahen et al[5] analyzed the clinical benefit of surgical drainage versus endoscopic drainage, which is more suitable for this type of comparison. Nineteen patients underwent endoscopic drainage, and 20 patients received surgical drainage. Two years after intervention, 75% patients with pancreaticojejunostomy were partially or completely pain-free, but complete or partial pain relief was achieved in only 32% of patients with endoscopic therapy. Cahen et al[5] concluded that the surgical drainage of pancreatic duct was more effective than endoscopic treatment in patients with obstruction of pancreatic duct due to chronic pancreatitis. In contrast, the data of our current series demonstrated that ERP failed in only 2 of 19 patients. Complete or partial pain relief was achieved in 17 of 19 patients after initial stent insertion. Approximately half of the patients benefited from endoscopic stent therapy 5 years after endoscopic intervention. The less effective outcome of endoscopic stent therapy in the Cahen study may result from the difficulty of managing the endoscopic group. The complication rate of the endoscopic group (58%) was approximately 4 times higher in their study compared to the average results of other studies[22,23].

Many patients present contraindications or refuse to undergo surgery due to the invasiveness of surgical procedures. Consequently, patients who were American Society of Anesthesiologists class IV, presented with portal vein thrombosis or declined to participate were excluded from the Cahen study[5]. Approximately 12% of patients with chronic pancreatitis exhibit portal hypertension[24]. Izbicki et al[25] evaluated the impact of concomitant nonhepatic portal hypertension in chronic pancreatitis on the outcomes after major pancreatic surgery. Patients with portal hypertension required significantly more blood transfusions and longer operative times than their nonhypertensive counterparts. The overall postoperative complication rate was significantly higher in this subgroup. Izbicki concluded that concomitant extrahepatic portal hypertension is a substantial risk in pancreatic surgery for chronic pancreatitis.

The major limitations of this study are the small number of patients, its single-center character and its non-randomized design. Therefore, randomized long-term follow-up studies with a larger number of patients are required.

In conclusion, endoscopic therapy proved to be a safe and effective alternative to surgery, and endoscopic therapy did not adversely affect the outcome of subsequent surgeries[26]. Our current data demonstrate that endoscopic therapy provided long-term benefits in more than half of the patients (57%) with chronic obstructive pancreatitis. The management of obstructive chronic pancreatitis should be individual. Patients with multiple morbidities profit from low invasive endoscopic therapy. Therefore, endoscopic stent therapy is the treatment of choice in inoperable patients or patients who refuse surgical treatment.

Obstruction of the pancreatic duct is a common feature of chronic pancreatitis, and it often requires interventional therapy. The optimal treatment for chronic pancreatitis is controversial among surgeons and endoscopists. The primary goal of both surgical and endoscopic drainage procedures is the restoration of pancreatic drainage to lower the pressure within the pancreatic duct and relieve pain.

This is the first prospective 5-year follow-up assessment of the incidence and treatment of relapse in patients with chronic obstructive pancreatitis after the successful completion of endoscopic stent therapy.

The current data demonstrate that endoscopic therapy provided long-term benefits in more than half of chronic obstructive pancreatitis patients. Most (57 %) of the patients remained free of relapse 5 years after endoscopic treatment. Endoscopic treatment was an effective alternative to surgery in cases of relapse.

These data suggest that endoscopic therapy is a safe, minimally invasive, and effective procedure in patients who experience pain attacks during chronic pancreatitis. Multimorbid patients benefit from the low invasiveness of endoscopic therapy. Therefore, endoscopic stent therapy should be the treatment of choice in patients who are inoperable or refuse surgical treatment.

Chronic pancreatitis is a continuous inflammation of the pancreas that produces morphological changes, such as calcifications, irregularities of the pancreas duct and the formation of pancreatic stones. The pathogenesis of pain in chronic pancreatitis is controversial. Interstitial hypertension, ongoing pancreatic ischemia, neuronal inflammation, and extrapancreatic complications may contribute to the pathogenesis of pain.

The current study provides interesting and clinically relevant data. The observed patient group was small, but the differences were obvious. The data support the benefit of long-term endoscopic therapy in a subgroup of patients.

P- Reviewers Seicean A, Prinz C, Drewes AM, Gerstenmaier JF S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Hines OJ, Reber HA. Pancreatic surgery. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21:568-572. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Bradley EL. Pancreatic duct pressure in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1982;144:313-316. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Madsen P, Winkler K. The intraductal pancreatic pressure in chronic obstructive pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1982;17:553-554. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Okazaki K, Yamamoto Y, Kagiyama S, Tamura S, Sakamoto Y, Morita M, Yamamoto Y. Pressure of papillary sphincter zone and pancreatic main duct in patients with alcoholic and idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol. 1988;3:457-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cahen DL, Gouma DJ, Nio Y, Rauws EA, Boermeester MA, Busch OR, Stoker J, Laméris JS, Dijkgraaf MG, Huibregtse K. Endoscopic versus surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct in chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:676-684. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Weber A, Schneider J, Neu B, Meining A, Born P, Schmid RM, Prinz C. Endoscopic stent therapy for patients with chronic pancreatitis: results from a prospective follow-up study. Pancreas. 2007;34:287-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ammann RW, Muellhaupt B. The natural history of pain in alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1132-1140. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Godil A, Chen YK. Endoscopic management of benign pancreatic disease. Pancreas. 2000;20:1-13. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Monkemuller KE, Kahl S, Malfertheiner P. Endoscopic therapy of chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis. 2004;22:280-291. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Neuhaus H. Therapeutic pancreatic endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2000;32:217-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Neuhaus H. Therapeutic pancreatic endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2004;36:8-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tringali A, Boskoski I, Costamagna G. The role of endoscopy in the therapy of chronic pancreatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:145-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Delhaye M, Arvanitakis M, Bali M, Matos C, Devière J. Endoscopic therapy for chronic pancreatitis. Scand J Surg. 2005;94:143-153. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB, Müllhaupt B, Cavallini G, Lankisch PG, Andersen JR, Dimagno EP, Andrén-Sandberg A, Domellöf L, Frulloni L. Cigarette smoking accelerates progression of alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2005;54:510-514. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Maisonneuve P, Frulloni L, Müllhaupt B, Faitini K, Cavallini G, Lowenfels AB, Ammann RW. Impact of smoking on patients with idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2006;33:163-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cavallini G, Talamini G, Vaona B, Bovo P, Filippini M, Rigo L, Angelini G, Vantini I, Riela A, Frulloni L. Effect of alcohol and smoking on pancreatic lithogenesis in the course of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1994;9:42-46. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Yadav D, Hawes RH, Brand RE, Anderson MA, Money ME, Banks PA, Bishop MD, Baillie J, Sherman S, DiSario J. Alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and the risk of recurrent acute and chronic pancreatitis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1035-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 317] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Schneider KJ, Scheer M, Suhr M, Clemens DL. Ethanol administration impairs pancreatic repair after injury. Pancreas. 2012;41:1272-1279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Talamini G, Bassi C, Falconi M, Sartori N, Vaona B, Bovo P, Benini L, Cavallini G, Pederzoli P, Vantini I. Smoking cessation at the clinical onset of chronic pancreatitis and risk of pancreatic calcifications. Pancreas. 2007;35:320-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Díte P, Ruzicka M, Zboril V, Novotný I. A prospective, randomized trial comparing endoscopic and surgical therapy for chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2003;35:553-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 384] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rösch T, Daniel S, Scholz M, Huibregtse K, Smits M, Schneider T, Ell C, Haber G, Riemann JF, Jakobs R. Endoscopic treatment of chronic pancreatitis: a multicenter study of 1000 patients with long-term follow-up. Endoscopy. 2002;34:765-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dumonceau JM, Devière J, Le Moine O, Delhaye M, Vandermeeren A, Baize M, Van Gansbeke D, Cremer M. Endoscopic pancreatic drainage in chronic pancreatitis associated with ductal stones: long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:547-555. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Bockhorn M, Gebauer F, Bogoevski D, Molmenti E, Cataldegirmen G, Vashist YK, Yekebas EF, Izbicki JR, Mann O. Chronic pancreatitis complicated by cavernous transformation of the portal vein: contraindication to surgery? Surgery. 2011;149:321-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Izbicki JR, Yekebas EF, Strate T, Eisenberger CF, Hosch SB, Steffani K, Knoefel WT. Extrahepatic portal hypertension in chronic pancreatitis: an old problem revisited. Ann Surg. 2002;236:82-89. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Boerma D, van Gulik TM, Rauws EA, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Outcome of pancreaticojejunostomy after previous endoscopic stenting in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:223-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |