Published online Nov 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i43.7594

Revised: September 16, 2013

Accepted: September 29, 2013

Published online: November 21, 2013

Processing time: 172 Days and 10.5 Hours

Ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) remains an unresolved and complicated situation in clinical practice, especially in the case of organ transplantation. Several factors contribute to its complexity; the depletion of energy during ischemia and the induction of oxidative stress during reperfusion initiate a cascade of pathways that lead to cell death and finally to severe organ injury. Recently, the sirtuin family of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent deacetylases has gained increasing attention from researchers, due to their involvement in the modulation of a wide variety of cellular functions. There are seven mammalian sirtuins and, among them, the nuclear/cytoplasmic sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) and the mitochondrial sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) are ubiquitously expressed in many tissue types. Sirtuins are known to play major roles in protecting against cellular stress and in controlling metabolic pathways, which are key processes during IRI. In this review, we mainly focus on SIRT1 and SIRT3 and examine their role in modulating pathways against energy depletion during ischemia and their involvement in oxidative stress, apoptosis, microcirculatory stress and inflammation during reperfusion. We present evidence of the beneficial effects of sirtuins against IRI and emphasize the importance of developing new strategies by enhancing their action.

Core tip: Sirtuins are responsible for the regulation of protein activation by deacetylating a range of proteins that play important roles in the pathophysiology of various diseases. The present review summarizes the beneficial effects of sirtuins 1 and 3, the two most prominent sirtuins involved in mammalian energy homeostasis and oxidative stress. We conclude that both sirtuins might be attractive targets for counteracting the detrimental effects of ischemia-reperfusion injury.

- Citation: Pantazi E, Zaouali MA, Bejaoui M, Folch-Puy E, Abdennebi HB, Roselló-Catafau J. Role of sirtuins in ischemia-reperfusion injury. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(43): 7594-7602

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i43/7594.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i43.7594

Sirtuins belong to the highly conserved class III histone deacetylases with homology to the yeast silent information regulator 2. To date, seven sirtuins have been described in mammals. They posses nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent deacetylase activity, with the exception of sirtuin 4 (SIRT4) which has only ADP-ribosyltransferase activity, and SIRT1 and SIRT6 which have not only deacetylase activity but also relatively weak ADP-ribosyltransferase activity[1]. Their enzymatic activity depends on their protein expression levels, the availability of NAD+ and the presence of proteins that modulate sirtuin enzymatic activity. For instance, SIRT1 expression increases during starvation or when cells are exposed to conditions of oxidative stress and DNA damage[2,3].

Sirtuins are found in several subcellular locations, including the nucleus (SIRT1, SIRT6, and SIRT7), cytosol (SIRT2), and mitochondria (SIRT3-SIRT5). In some studies, however, SIRT1 has been found to possess cytosolic activity, and SIRT2 has been found to be associated with nuclear proteins[4].

Several recent studies have shown that sirtuins regulate a wide variety of cellular processes, such as gene transcription, metabolism and cellular stress response[5-7]. SIRT1, the most studied member of the family, plays an important role in several processes ranging from cell cycle regulation to energy homeostasis[8,9]. SIRT3 has recently been reported to have a considerable impact on mitochondrial energy metabolism and function[10,11]. In this review, we will focus mainly on SIRT1 and SIRT3 functions in ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI).

IRI is one of the most significant problems in graft injury, contributing to primary graft dysfunction or non-function after organ transplantation[12-14]. Many factors contribute to IRI. First of all, the loss of oxygen supply during ischemia results in the reduction of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis and subsequent changes in ion influx, acidosis and cell swelling which may eventually lead to cell death. The restoration of blood flow is followed by an excessive acute inflammatory response triggering the reperfusion injury. Although the ischemic insult causes significant damage in cells, the tissue injury generated during reperfusion is much more severe. On reperfusion, oxygen is suddenly available, and metabolism proceeds rapidly, resulting in a sudden production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), cytokines and chemokines which increase the accumulation of inflammatory cells (monocytes, dendritic cells and granulocytes). In combination with excessive nitric oxide (NO), ROS are able to induce DNA damage and activate various types of cell death pathways[15-17].

Understanding the mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of IRI is the first step to mitigate its adverse effects. Sirtuins are known to regulate many important processes in cell physiology, including those affecting IRI, such as cellular metabolism and stress response. This makes them potentially appealing targets for therapeutic interventions against IR-induced injury.

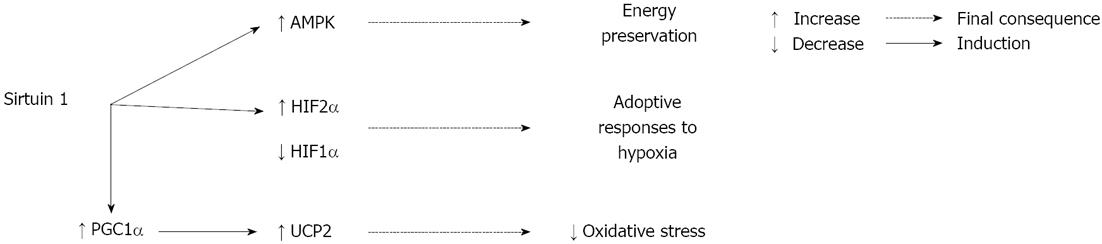

The low energy state during ischemia results in activation of adenosine monophosphate protein kinase (AMPK), a fuel-sensing enzyme that is positively regulated by an increased ratio of adenosine monophosphate to ATP. When AMPK is activated, it stimulates processes that restore ATP levels (e.g., fatty acid oxidation) and inhibits other processes that consume ATP (e.g., protein synthesis)[18]. The activity of sirtuins is directly related to the metabolic state of the cell due to their dependence on NAD+. Suchankova and collaborators found that glucose-induced changes in AMPK are linked to alterations in the NAD+/reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide ratio and SIRT1 abundance and activity[19]. These results may suggest a possible interaction between AMPK and SIRT1 in ischemic conditions. Indeed, an activator of AMPK, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside, has been found to improve IRI and increase SIRT1 expression in the rat kidney[20]. Furthermore, enhancing the activity of SIRT1 through the application of resveratrol, a SIRT1 activator, has been demonstrated to protect against cerebral ischemia[21].

Another element that plays an essential role in triggering cellular protection and preventing metabolic alterations caused by oxygen deprivation is hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs). Mammals possess three isoforms of HIFα, of which HIF1α and HIF2α are the most structurally similar and the best characterized. During hypoxia, protein levels of HIF2α increase slightly, but it presents significant activation, which suggests that its activity is regulated by additional post-translational mechanisms. One of these post-translational modulations may be deacetylation, since in hypoxic Hep3B cells SIRT1 deacetylates lysine residues in the HIF2α protein, enhancing its transcriptional activity[22].

Additionally, SIRT1 interacts with HIF1α, but in this case SIRT1 represses HIF1α transcriptional activity[23]. Under hypoxic stress, decreased cellular NAD+ downregulates SIRT1, increases HIF1α acetylation, and thereby promotes the expression of HIF1α target genes[23]. Interestingly, other studies have shown that HIF2α compete with HIF1α for binding to SIRT1[24]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that SIRT6 is also linked to HIF1α by repressing the transcription of HIF1α target genes[25].

Likewise, the effects of SIRT3 appear to be protective in the context of hypoxic stress in human cancer cells. SIRT3 overexpression resulted in decreased ROS production, impediment of HIF1α stabilization and subsequent suppression of tumorigenesis[26,27]. However, the effect of SIRT3 in HIF1α stabilization in IRI has not been reported to date.

One of the most important factors involved in the metabolic control regulated by SIRT1 is peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α (PGC1α), a transcriptional co-activator of many nuclear receptors and transcriptional factors. SIRT1 functionally interacts with PGC1α and deacetylates it, thus inducing the expression of mitochondrial proteins involved in ATP-generating pathways[28]. Increased PGC1α activity is also associated with lower levels of oxidative damage during ischemia, as shown by the decrease ROS scavenging in rodents lacking PGC1α subjected to global ischemia[29]. Furthermore, the uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2), an inner mitochondrial membrane protein, regulates the proton electrochemical gradient and in neuronal cells PGC1α is required for the induction of UCP2 and subsequent protection against oxidative stress[30]. It has also been shown that enhanced activity of SIRT1 during ischemic preconditioning (IPC) or resveratrol preconditioning confers protection against cerebral ischemia by reducing UCP2 levels, which results in increased ATP levels[21]. However, a more recent study associated the protective effect of resveratrol against oxidative stress in cerebral ischemia with increased levels of SIRT1/PGC1α and UCP2[31]. Moreover, the exact role of UCP2 during ischemia is not fully understood, as studies of its effects have produced conflicting results[32-35].

Deprivation of oxygen to the grafts during ischemia induces severe lesions, but the most important damage is caused during reperfusion, when oxygen entry to the organ is restored. During reperfusion, the cellular metabolism returns to aerobic pathways, which results in the generation of a wide variety of ROS, including superoxide, hydrogen peroxide and reactive nitrogen species, such as peroxynitrite. ROS are mainly produced in mitochondria and trigger several phenomena, including accumulation of Ca2+, caspase activation, cytokine upregulation, lipid, protein and DNA damage[36-38]. ROS can be eliminated by enzymatic pathways including manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), catalase (Cat) and peroxidases. Imbalance between ROS generation and elimination produces oxidative stress[15,16].

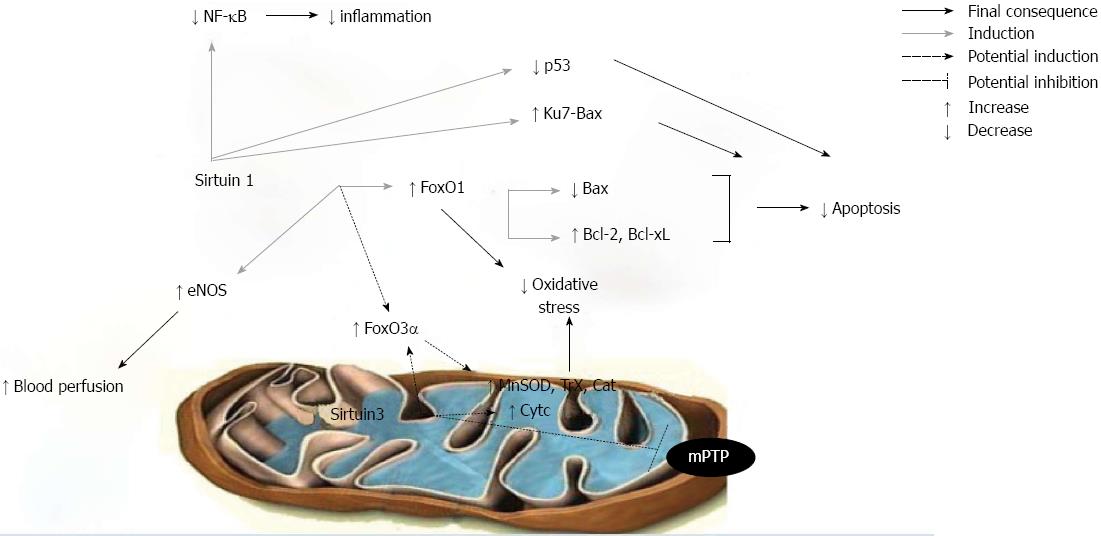

Various reports in cardiomyocytes have demonstrated the protective role of SIRT1 against oxidative stress[39,40]. Hearts overexpressing SIRT1 were more resistant to oxidative stress in response to IRI, as SIRT1 upregulated the expression of anti-oxidants like MnSOD and thioredoxin 1[41]. SIRT1 also deacetylated Forkhead box-containing protein O (FoxO) 1 transcription factor, inducing its nuclear translocation and subsequent transcription of anti-oxidant molecules[41,42]. Moreover, the question of whether SIRT1 can induce the transcription of other FoxO transcription factors, like FoxO3α, has not yet been investigated. However, the levels of SIRT1 activation are decisive for its protective role, as very high cardiac SIRT1 expression induces mitochondrial dysfunction and increases oxidative stress[39]. Furthermore, in a model of kidney IRI, the protective effect of SIRT1 against oxidative stress has also been demonstrated since SIRT1 upregulated Cat levels and maintained peroxisome number and function[43].

Although mitochondrial sirtuins (SIRT3-SIRT5) have not been studied as extensively as SIRT1, an increasing body of evidence indicates the importance of SIRT3 in mitochondrial biology and function. Lombard et al[44] demonstrated that SIRT3 is the dominant mitochondrial deacetylase, as a significant number of mitochondrial proteins are hyperacetylated in SIRT3-/- mice. SIRT3 deacetylates and thus enhances the activity of various proteins that appear to be an important part of the antioxidative defense mechanisms of mitochondria, such as MnSOD[45,46], regulatory proteins of the glutathione[47-49] and thioredoxin system[50].

Transcriptional upregulation of the antioxidant enzymes MnSOD, Cat and peroxiredoxin can also be achieved by FoxO3α transcription factor, which is translocated to the nucleus after being deacetylated by SIRT3[51,52]. Furthermore, SIRT3 is necessary for the enhanced expression of cytochrome c, which presents peroxidase- and superoxidase-scavenging capacity[47,49,53]. However, a similar anti-oxidant effect of SIRT3 in models of IRI has not yet been established.

A wide array of functional alterations develop in mitochondria during reperfusion injury[36,54]. In healthy cells, their primary function is the provision of ATP through oxidative phosphorylation in order to meet the high energy demands. There is increasing evidence of the involvement of a multi-protein complex called the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) in the decline in mitochondrial function, which is a common finding during reperfusion injury[55-57]. SIRT3 is known to deacetylate the regulatory component of the mPTP, cyclophilin D, and thereby reduce its activity and the subsequent mitochondrial swelling in the heart[58]. It has also been shown that SIRT4 interacts with the adenine nucleotide translocator, another component of mPTP, and that SIRT5 deacetylates cytochrome c, but the physiological importance of these interactions has not yet been established[59,60], especially in models of IRI.

Microcirculatory alterations play an important part in IRI. During the ischemic period, vascular hypoxia can cause increased vascular permeability. After reperfusion, complement system activation, leukocyte-endothelial cell adhesion and platelet-leukocyte aggregation further aggravate microvascular dysfunction[61].

NO produced by endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) is a key regulator of endothelial function, as it opposes the vasoconstrictive actions of endothelins and provokes vasodilatation. Thus, it can abrogate the microcirculatory stress generated during reperfusion[62]. However, NO produced by inducible NO synthase (iNOS) exacerbates IRI through the NOS-derived superoxide production or the generation of peroxynitrite[12]. There is a large body of evidence in favor of the relationship between eNOS and SIRT1; SIRT1 interacts and modifies the acetylation state of eNOS, resulting in the activation of the enzyme[63-65]. In SIRT1+/+ hearts subjected to IRI SIRT1 was associated with eNOS activation[66]. SIRT1 activation by resveratrol protected against subacute intestinal IRI by reducing the NO production through iNOS[67] Moreover, various experimental models showed that resveratrol inhibits endothelin-1 levels, providing better regulation of vascular tone[68-70]. However, a recent study in human umbilical vein endothelial cells has shown that the inhibitory effects of resveratrol on endothelin-1 levels are SIRT1-independent[71].

IRI results in a profound inflammatory tissue reaction with immune cells infiltrating the tissue. The damage is mediated by various cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, and compounds of the extracellular matrix. The expression of these factors is regulated by specific transcription factors with nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) being one of the key modulators of inflammation. After activation, the transcription factor migrates to the nucleus and enhances the transcription of pro-inflammatory genes potentiating the inflammatory response. This is followed by an infiltration of lymphocytes, mononuclear cells/macrophages, and granulocytes into the injured tissue[72-74].

In this way, SIRT1 plays an important role in neuroprotection against brain ischemia by deacetylation and subsequent inhibition of p53 and NF-κB pathways[75]. In SIRT1+/+ hearts subjected to IRI SIRT1 was correlated with decreased acetylation of NF-κB and possible prevention of inflammation[66]. Moreover, the anti-inflammatory action of SIRT1 by deacetylating NF-κB and thus inhibiting the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules has also been demonstrated in human aortic endothelial cells[74].

Apoptotic cell death is a well known mechanism involved in IRI which occurs via activation of caspases that cleave DNA and other cellular components[16,17,76]. There is evidence that SIRT1 is associated with longevity in mammals and enhances mammalian cell survival under stress conditions via regulating the specific substrates[77-79]. In fact, several studies have mentioned the anti-apoptotic effect of SIRT1 in IRI. SIRT1 deacetylates known mediators of apoptosis, such as the tumor-suppressor p53, resulting in inhibition of its transcriptional activity[80,81] . SIRT1 also deacetylates the DNA repair factor Ku70[2,82,83]; thus Ku70 prevents the translocation of Bax, a pro-apoptotic B cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) family protein, to the mitochondria. In ischemic kidney and brain SIRT1 has been identified as an important survival mediator, given that increased SIRT1 was associated with reduced p53 expression and apoptosis[75,84]. SIRT1 also modulates apoptosis-related molecules through the deacetylation of the FoxO family of transcription factors. During IRI in heart-specific SIRT1+/+ transgenic mice, SIRT1 induces nuclear translocation of FoxO1, which upregulates the anti-apoptotic factors Bcl-2 and Bcl-like X and downregulates Bax[41]. As regards other members of the FoxO family, Brunet et al[85] revealed a dual role of SIRT1 in the cell cycle depending on stress conditions; SIRT1 inhibited the ability of FoxO3 to induce cell death, thus promoting cell survival and, surprisingly, it also increased the ability of FoxO3 to induce cell cycle arrest and resistance to oxidative stress.

A possible pro-apoptotic role of SIRT1 in IRI has not been reported previously. However, studies in human embryonic kidney cells have revealed that SIRT1 can promote cell death by inhibiting NF-κB in response to tumor necrosis factor alpha[86]. Further investigation is required to define the conditions under which SIRT1 may promote apoptosis.

Apoptotic pathways are known to be initiated during reperfusion upon the opening of the mPTP which leads to the release of caspase-activating molecules[87,88]. Since SIRT3 is located in the mitochondria, it may be involved in anti-apoptotic pathways. In this regard, SIRT3 protects various types of cells from apoptotic cell death triggered by genotoxic or oxidative stress[89-92]. The pro-apoptotic role of SIRT3 has also been associated with tumor suppression and restraint of ROS[93]. However, SIRT3 has also been reported to contribute to Bcl-2- and JNK-related apoptotic pathways in human colorectal carcinoma cells[94]. In any case, the potential anti-apoptotic mechanisms of SIRT3 during IRI are yet to be elucidated.

A wide range of pathological processes contribute to IRI. Particularly during organ transplantation, IRI contributes to early graft dysfunction. For this reason, it is important to gain additional mechanistic insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying this injury. In the past few years, sirtuins have emerged as critical modulators of various cellular processes, including those that contribute to the pathogenesis of IRI.

In this paper, we have reviewed the signaling pathways of SIRT1 and SIRT3 protection in IRI. SIRT1 has been shown to exert its beneficial effect against oxidative stress, hypoxic injury or inflammation associated with IRI by activating FoxO1, PGC1α and HIF2α or by inhibiting NF-κB transcription factors (Figures 1 and 2). SIRT3’s protective role in IRI is mainly mediated by activating FoxO3α and mitochondrial anti-oxidant enzymes (Figure 2). Investigations that can further determine other intracellular signaling, trafficking and post-translational modifications by SIRT1 and SIRT3 in a variety of cell systems and environments will allow us to translate this knowledge into effective treatment strategies that will be applicable in multiple disorders.

Numerous studies have demonstrated key roles for SIRT1 and SIRT3 in brain, heart and kidney IRI. However, the protective effect of these sirtuins against ischemic processes in other organs such as the liver has not yet been demonstrated. The relevance of SIRT3 in the hepatic metabolism has been confirmed in a study showing that its overexpression in hepatocytes decreased the accumulation of lipids via AMPK activation[95]. Furthermore, deletion of hepatic SIRT1 resulted in hepatic steatosis, hepatic inflammation and endoplasmatic reticulum stress[96]. Since SIRT1 and SIRT3 have been shown to exert a beneficial effect in regulating hepatic fatty acid metabolism, it would be interesting to investigate their role in the context of liver transplantation. Currently, the shortage of organs for transplantation has obliged physicians to utilize marginal grafts, including grafts with moderate steatosis. Steatotic livers exhibit a more severe inflammatory reaction and more exacerbated oxidative stress and consequently a higher vulnerability to IRI[12]. Thus, activating SIRT1 and SIRT3 might be a potential strategy to protect steatotic livers from IRI as well as to expand the donor pool for liver transplantation. In fact, in preliminary studies our group observed that SIRT1 is involved in the protective mechanisms against IRI elicited by IPC in fatty livers.

For this reason, both surgical and pharmacological strategies should be developed to enhance the activity of sirtuins and thus mitigate the detrimental effect of IRI. Recent studies have highlighted the important role of SIRT1 in IPC-mediated protection in the heart and brain; in IPC brain, SIRT1 prevents neuronal death[97], whereas during cardiac IPC, SIRT1 regulates HIF1α protein levels[98,99]. A recent review has also associated SIRT1 with the protective effects of hyperbaric oxygen preconditioning against apoptosis in the rat brain[100]. However, it is still to be established whether SIRT1 contributes to the protective effects of preconditioning through the regulation of other signalling pathways. Furthermore, its possible implication in IPC related mechanisms in other organs, including the liver or kidney, remains to be elucidated.

Nor has the potential role of sirtuins in cold ischemia and reperfusion yet been established. In the context of liver IRI, a previous study by our group demonstrated that during normoxic reperfusion, after cold ischemia, the presence of NO favors HIF1α accumulation, also promoting the activation of other cytoprotective proteins, such as heme oxygenase-1[101]. Among these cytoprotective proteins, SIRT1 may be ideally suited to enhance the protective effect.

This review summarizes the basic mediators of IRI influenced by the action of SIRT1 and SIRT3 and highlights the importance of their regulation. Future research should aim to elucidate the complete action of all members of the sirtuins family in IRI, and to develop pharmacological strategies that can allow their action to be modulated.

P- Reviewers: Du C, Zhang Y S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Nakagawa T, Guarente L. Sirtuins at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:833-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cohen HY, Miller C, Bitterman KJ, Wall NR, Hekking B, Kessler B, Howitz KT, Gorospe M, de Cabo R, Sinclair DA. Calorie restriction promotes mammalian cell survival by inducing the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;305:390-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1456] [Cited by in RCA: 1504] [Article Influence: 71.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rodgers JT, Lerin C, Haas W, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM, Puigserver P. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1alpha and SIRT1. Nature. 2005;434:113-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2318] [Cited by in RCA: 2502] [Article Influence: 125.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Morris KC, Lin HW, Thompson JW, Perez-Pinzon MA. Pathways for ischemic cytoprotection: role of sirtuins in caloric restriction, resveratrol, and ischemic preconditioning. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:1003-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nogueiras R, Habegger KM, Chaudhary N, Finan B, Banks AS, Dietrich MO, Horvath TL, Sinclair DA, Pfluger PT, Tschöp MH. Sirtuin 1 and sirtuin 3: physiological modulators of metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:1479-1514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in RCA: 547] [Article Influence: 42.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pillarisetti S. A review of Sirt1 and Sirt1 modulators in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Recent Pat Cardiovasc Drug Discov. 2008;3:156-164. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Gorenne I, Kumar S, Gray K, Figg N, Yu H, Mercer J, Bennett M. Vascular smooth muscle cell sirtuin 1 protects against DNA damage and inhibits atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2013;127:386-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Al Massadi O, Quiñones M, Lear P, Dieguez C, Nogueiras R. The Brain: A New Organ for the Metabolic Actions of SIRT1. Horm Metab Res. 2013;Aug 15; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gillum MP, Kotas ME, Erion DM, Kursawe R, Chatterjee P, Nead KT, Muise ES, Hsiao JJ, Frederick DW, Yonemitsu S. SirT1 regulates adipose tissue inflammation. Diabetes. 2011;60:3235-3245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Brenmoehl J, Hoeflich A. Dual control of mitochondrial biogenesis by sirtuin 1 and sirtuin 3. Mitochondrion. 2013;Apr 11; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rardin MJ, Newman JC, Held JM, Cusack MP, Sorensen DJ, Li B, Schilling B, Mooney SD, Kahn CR, Verdin E. Label-free quantitative proteomics of the lysine acetylome in mitochondria identifies substrates of SIRT3 in metabolic pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:6601-6606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 345] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Casillas-Ramírez A, Mosbah IB, Ramalho F, Roselló-Catafau J, Peralta C. Past and future approaches to ischemia-reperfusion lesion associated with liver transplantation. Life Sci. 2006;79:1881-1894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Treska V, Kobr J, Hasman D, Racek J, Trefil L, Reischig T, Hes O, Kuntscher V, Molacek J, Treska I. Ischemia-reperfusion injury in kidney transplantation from non-heart-beating donor--do antioxidants or antiinflammatory drugs play any role? Bratisl Lek Listy. 2009;110:133-136. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Schemmer P, Lemasters JJ, Clavien PA. Ischemia/Reperfusion injury in liver surgery and transplantation. HPB Surg. 2012;2012:453295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Czubkowski P, Socha P, Pawlowska J. Oxidative stress in liver transplant recipients. Ann Transplant. 2011;16:99-108. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Datta G, Fuller BJ, Davidson BR. Molecular mechanisms of liver ischemia reperfusion injury: insights from transgenic knockout models. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1683-1698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Murphy E, Steenbergen C. Mechanisms underlying acute protection from cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:581-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1161] [Cited by in RCA: 1121] [Article Influence: 65.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ruderman NB, Xu XJ, Nelson L, Cacicedo JM, Saha AK, Lan F, Ido Y. AMPK and SIRT1: a long-standing partnership? Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E751-E760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 600] [Cited by in RCA: 705] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Suchankova G, Nelson LE, Gerhart-Hines Z, Kelly M, Gauthier MS, Saha AK, Ido Y, Puigserver P, Ruderman NB. Concurrent regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase and SIRT1 in mammalian cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;378:836-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lempiäinen J, Finckenberg P, Levijoki J, Mervaala E. AMPK activator AICAR ameliorates ischaemia reperfusion injury in the rat kidney. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166:1905-1915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Della-Morte D, Dave KR, DeFazio RA, Bao YC, Raval AP, Perez-Pinzon MA. Resveratrol pretreatment protects rat brain from cerebral ischemic damage via a sirtuin 1-uncoupling protein 2 pathway. Neuroscience. 2009;159:993-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dioum EM, Chen R, Alexander MS, Zhang Q, Hogg RT, Gerard RD, Garcia JA. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha signaling by the stress-responsive deacetylase sirtuin 1. Science. 2009;324:1289-1293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 353] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lim JH, Lee YM, Chun YS, Chen J, Kim JE, Park JW. Sirtuin 1 modulates cellular responses to hypoxia by deacetylating hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Mol Cell. 2010;38:864-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 508] [Cited by in RCA: 601] [Article Influence: 40.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Majmundar AJ, Wong WJ, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40:294-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1923] [Cited by in RCA: 1817] [Article Influence: 121.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhong L, D’Urso A, Toiber D, Sebastian C, Henry RE, Vadysirisack DD, Guimaraes A, Marinelli B, Wikstrom JD, Nir T. The histone deacetylase Sirt6 regulates glucose homeostasis via Hif1alpha. Cell. 2010;140:280-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 847] [Cited by in RCA: 795] [Article Influence: 53.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bell EL, Emerling BM, Ricoult SJ, Guarente L. SirT3 suppresses hypoxia inducible factor 1α and tumor growth by inhibiting mitochondrial ROS production. Oncogene. 2011;30:2986-2996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 365] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Finley LW, Carracedo A, Lee J, Souza A, Egia A, Zhang J, Teruya-Feldstein J, Moreira PI, Cardoso SM, Clish CB. SIRT3 opposes reprogramming of cancer cell metabolism through HIF1α destabilization. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:416-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 675] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 46.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Nemoto S, Fergusson MM, Finkel T. SIRT1 functionally interacts with the metabolic regulator and transcriptional coactivator PGC-1{alpha}. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16456-16460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 786] [Cited by in RCA: 861] [Article Influence: 43.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chen SD, Lin TK, Yang DI, Lee SY, Shaw FZ, Liou CW, Chuang YC. Protective effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors gamma coactivator-1alpha against neuronal cell death in the hippocampal CA1 subfield after transient global ischemia. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:605-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | St-Pierre J, Drori S, Uldry M, Silvaggi JM, Rhee J, Jäger S, Handschin C, Zheng K, Lin J, Yang W. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell. 2006;127:397-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1871] [Cited by in RCA: 1816] [Article Influence: 95.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Shin JA, Lee KE, Kim HS, Park EM. Acute resveratrol treatment modulates multiple signaling pathways in the ischemic brain. Neurochem Res. 2012;37:2686-2696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mattiasson G, Shamloo M, Gido G, Mathi K, Tomasevic G, Yi S, Warden CH, Castilho RF, Melcher T, Gonzalez-Zulueta M. Uncoupling protein-2 prevents neuronal death and diminishes brain dysfunction after stroke and brain trauma. Nat Med. 2003;9:1062-1068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in RCA: 412] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | McLeod CJ, Aziz A, Hoyt RF, McCoy JP, Sack MN. Uncoupling proteins 2 and 3 function in concert to augment tolerance to cardiac ischemia. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33470-33476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | de Bilbao F, Arsenijevic D, Vallet P, Hjelle OP, Ottersen OP, Bouras C, Raffin Y, Abou K, Langhans W, Collins S. Resistance to cerebral ischemic injury in UCP2 knockout mice: evidence for a role of UCP2 as a regulator of mitochondrial glutathione levels. J Neurochem. 2004;89:1283-1292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Bodyak N, Rigor DL, Chen YS, Han Y, Bisping E, Pu WT, Kang PM. Uncoupling protein 2 modulates cell viability in adult rat cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H829-H835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sanderson TH, Reynolds CA, Kumar R, Przyklenk K, Hüttemann M. Molecular mechanisms of ischemia-reperfusion injury in brain: pivotal role of the mitochondrial membrane potential in reactive oxygen species generation. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;47:9-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 404] [Cited by in RCA: 504] [Article Influence: 38.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Rodrigo R, Prieto JC, Castillo R. Cardioprotection against ischaemia/reperfusion by vitamins C and E plus n-3 fatty acids: molecular mechanisms and potential clinical applications. Clin Sci (Lond). 2013;124:1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 38. | Raedschelders K, Ansley DM, Chen DD. The cellular and molecular origin of reactive oxygen species generation during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;133:230-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Alcendor RR, Gao S, Zhai P, Zablocki D, Holle E, Yu X, Tian B, Wagner T, Vatner SF, Sadoshima J. Sirt1 regulates aging and resistance to oxidative stress in the heart. Circ Res. 2007;100:1512-1521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 784] [Cited by in RCA: 886] [Article Influence: 49.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Vinciguerra M, Santini MP, Martinez C, Pazienza V, Claycomb WC, Giuliani A, Rosenthal N. mIGF-1/JNK1/SirT1 signaling confers protection against oxidative stress in the heart. Aging Cell. 2012;11:139-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Hsu CP, Zhai P, Yamamoto T, Maejima Y, Matsushima S, Hariharan N, Shao D, Takagi H, Oka S, Sadoshima J. Silent information regulator 1 protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation. 2010;122:2170-2182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 461] [Cited by in RCA: 458] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Daitoku H, Hatta M, Matsuzaki H, Aratani S, Ohshima T, Miyagishi M, Nakajima T, Fukamizu A. Silent information regulator 2 potentiates Foxo1-mediated transcription through its deacetylase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10042-10047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 462] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Hasegawa K, Wakino S, Yoshioka K, Tatematsu S, Hara Y, Minakuchi H, Sueyasu K, Washida N, Tokuyama H, Tzukerman M. Kidney-specific overexpression of Sirt1 protects against acute kidney injury by retaining peroxisome function. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13045-13056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Lombard DB, Alt FW, Cheng HL, Bunkenborg J, Streeper RS, Mostoslavsky R, Kim J, Yancopoulos G, Valenzuela D, Murphy A. Mammalian Sir2 homolog SIRT3 regulates global mitochondrial lysine acetylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:8807-8814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 980] [Cited by in RCA: 989] [Article Influence: 54.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Chen Y, Zhang J, Lin Y, Lei Q, Guan KL, Zhao S, Xiong Y. Tumour suppressor SIRT3 deacetylates and activates manganese superoxide dismutase to scavenge ROS. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:534-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in RCA: 448] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Qiu X, Brown K, Hirschey MD, Verdin E, Chen D. Calorie restriction reduces oxidative stress by SIRT3-mediated SOD2 activation. Cell Metab. 2010;12:662-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 928] [Cited by in RCA: 1027] [Article Influence: 68.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Zhao S, Xu W, Jiang W, Yu W, Lin Y, Zhang T, Yao J, Zhou L, Zeng Y, Li H. Regulation of cellular metabolism by protein lysine acetylation. Science. 2010;327:1000-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1637] [Cited by in RCA: 1557] [Article Influence: 103.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Someya S, Yu W, Hallows WC, Xu J, Vann JM, Leeuwenburgh C, Tanokura M, Denu JM, Prolla TA. Sirt3 mediates reduction of oxidative damage and prevention of age-related hearing loss under caloric restriction. Cell. 2010;143:802-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 956] [Cited by in RCA: 905] [Article Influence: 60.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Choudhary C, Kumar C, Gnad F, Nielsen ML, Rehman M, Walther TC, Olsen JV, Mann M. Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science. 2009;325:834-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3070] [Cited by in RCA: 3258] [Article Influence: 203.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Palacios OM, Carmona JJ, Michan S, Chen KY, Manabe Y, Ward JL, Goodyear LJ, Tong Q. Diet and exercise signals regulate SIRT3 and activate AMPK and PGC-1alpha in skeletal muscle. Aging (Albany NY). 2009;1:771-783. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Sundaresan NR, Gupta M, Kim G, Rajamohan SB, Isbatan A, Gupta MP. Sirt3 blocks the cardiac hypertrophic response by augmenting Foxo3a-dependent antioxidant defense mechanisms in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2758-2771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 524] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Jacobs KM, Pennington JD, Bisht KS, Aykin-Burns N, Kim HS, Mishra M, Sun L, Nguyen P, Ahn BH, Leclerc J. SIRT3 interacts with the daf-16 homolog FOXO3a in the mitochondria, as well as increases FOXO3a dependent gene expression. Int J Biol Sci. 2008;4:291-299. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Kong X, Wang R, Xue Y, Liu X, Zhang H, Chen Y, Fang F, Chang Y. Sirtuin 3, a new target of PGC-1alpha, plays an important role in the suppression of ROS and mitochondrial biogenesis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 510] [Cited by in RCA: 583] [Article Influence: 38.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Andrews DT, Royse C, Royse AG. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its role in anaesthesia-triggered cellular protection during ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2012;40:46-70. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Halestrap AP. Calcium, mitochondria and reperfusion injury: a pore way to die. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:232-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Halestrap AP, Clarke SJ, Javadov SA. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening during myocardial reperfusion--a target for cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:372-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 869] [Cited by in RCA: 860] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Shahzad T, Kasseckert SA, Iraqi W, Johnson V, Schulz R, Schlüter KD, Dörr O, Parahuleva M, Hamm C, Ladilov Y. Mechanisms involved in postconditioning protection of cardiomyocytes against acute reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;58:209-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Hafner AV, Dai J, Gomes AP, Xiao CY, Palmeira CM, Rosenzweig A, Sinclair DA. Regulation of the mPTP by SIRT3-mediated deacetylation of CypD at lysine 166 suppresses age-related cardiac hypertrophy. Aging (Albany NY). 2010;2:914-923. [PubMed] |

| 59. | Ahuja N, Schwer B, Carobbio S, Waltregny D, North BJ, Castronovo V, Maechler P, Verdin E. Regulation of insulin secretion by SIRT4, a mitochondrial ADP-ribosyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33583-33592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 302] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Schlicker C, Gertz M, Papatheodorou P, Kachholz B, Becker CF, Steegborn C. Substrates and regulation mechanisms for the human mitochondrial sirtuins Sirt3 and Sirt5. J Mol Biol. 2008;382:790-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 427] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Eltzschig HK, Collard CD. Vascular ischaemia and reperfusion injury. Br Med Bull. 2004;70:71-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Schmitt CA, Heiss EH, Dirsch VM. Effect of resveratrol on endothelial cell function: Molecular mechanisms. Biofactors. 2010;36:342-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Ota H, Eto M, Ogawa S, Iijima K, Akishita M, Ouchi Y. SIRT1/eNOS axis as a potential target against vascular senescence, dysfunction and atherosclerosis. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2010;17:431-435. [PubMed] |

| 64. | Donato AJ, Magerko KA, Lawson BR, Durrant JR, Lesniewski LA, Seals DR. SIRT-1 and vascular endothelial dysfunction with ageing in mice and humans. J Physiol. 2011;589:4545-4554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Mattagajasingh I, Kim CS, Naqvi A, Yamamori T, Hoffman TA, Jung SB, DeRicco J, Kasuno K, Irani K. SIRT1 promotes endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation by activating endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14855-14860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 640] [Cited by in RCA: 695] [Article Influence: 38.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Nadtochiy SM, Yao H, McBurney MW, Gu W, Guarente L, Rahman I, Brookes PS. SIRT1-mediated acute cardioprotection. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1506-H1512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Dong W, Li F, Pan Z, Liu S, Yu H, Wang X, Bi S, Zhang W. Resveratrol ameliorates subacute intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Surg Res. 2013;185:182-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Liu JC, Chen JJ, Chan P, Cheng CF, Cheng TH. Inhibition of cyclic strain-induced endothelin-1 gene expression by resveratrol. Hypertension. 2003;42:1198-1205. [PubMed] |

| 69. | Zou JG, Wang ZR, Huang YZ, Cao KJ, Wu JM. Effect of red wine and wine polyphenol resveratrol on endothelial function in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Int J Mol Med. 2003;11:317-320. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Liu Z, Song Y, Zhang X, Liu Z, Zhang W, Mao W, Wang W, Cui W, Zhang X, Jia X. Effects of trans-resveratrol on hypertension-induced cardiac hypertrophy using the partially nephrectomized rat model. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2005;32:1049-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Yang J, Wang N, Li J, Zhang J, Feng P. Effects of resveratrol on NO secretion stimulated by insulin and its dependence on SIRT1 in high glucose cultured endothelial cells. Endocrine. 2010;37:365-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Fondevila C, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury--a fresh look. Exp Mol Pathol. 2003;74:86-93. [PubMed] |

| 73. | Stein S, Matter CM. Protective roles of SIRT1 in atherosclerosis. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:640-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Stein S, Schäfer N, Breitenstein A, Besler C, Winnik S, Lohmann C, Heinrich K, Brokopp CE, Handschin C, Landmesser U. SIRT1 reduces endothelial activation without affecting vascular function in ApoE-/- mice. Aging (Albany NY). 2010;2:353-360. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Hernández-Jiménez M, Hurtado O, Cuartero MI, Ballesteros I, Moraga A, Pradillo JM, McBurney MW, Lizasoain I, Moro MA. Silent information regulator 1 protects the brain against cerebral ischemic damage. Stroke. 2013;44:2333-2337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Kosieradzki M, Rowiński W. Ischemia/reperfusion injury in kidney transplantation: mechanisms and prevention. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:3279-3288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Bordone L, Cohen D, Robinson A, Motta MC, van Veen E, Czopik A, Steele AD, Crowe H, Marmor S, Luo J. SIRT1 transgenic mice show phenotypes resembling calorie restriction. Aging Cell. 2007;6:759-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 530] [Cited by in RCA: 543] [Article Influence: 30.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Satoh A, Brace CS, Rensing N, Cliften P, Wozniak DF, Herzog ED, Yamada KA, Imai S. Sirt1 extends life span and delays aging in mice through the regulation of Nk2 homeobox 1 in the DMH and LH. Cell Metab. 2013;18:416-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 516] [Cited by in RCA: 562] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Radak Z, Koltai E, Taylor AW, Higuchi M, Kumagai S, Ohno H, Goto S, Boldogh I. Redox-regulating sirtuins in aging, caloric restriction, and exercise. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;58:87-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Vaziri H, Dessain SK, Ng Eaton E, Imai SI, Frye RA, Pandita TK, Guarente L, Weinberg RA. hSIR2(SIRT1) functions as an NAD-dependent p53 deacetylase. Cell. 2001;107:149-159. [PubMed] |

| 81. | Cheng HL, Mostoslavsky R, Saito S, Manis JP, Gu Y, Patel P, Bronson R, Appella E, Alt FW, Chua KF. Developmental defects and p53 hyperacetylation in Sir2 homolog (SIRT1)-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10794-10799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 863] [Cited by in RCA: 916] [Article Influence: 41.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Anekonda TS, Adamus G. Resveratrol prevents antibody-induced apoptotic death of retinal cells through upregulation of Sirt1 and Ku70. BMC Res Notes. 2008;1:122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Jeong J, Juhn K, Lee H, Kim SH, Min BH, Lee KM, Cho MH, Park GH, Lee KH. SIRT1 promotes DNA repair activity and deacetylation of Ku70. Exp Mol Med. 2007;39:8-13. [PubMed] |

| 84. | Fan H, Yang HC, You L, Wang YY, He WJ, Hao CM. The histone deacetylase, SIRT1, contributes to the resistance of young mice to ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2013;83:404-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Brunet A, Sweeney LB, Sturgill JF, Chua KF, Greer PL, Lin Y, Tran H, Ross SE, Mostoslavsky R, Cohen HY. Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;303:2011-2015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2498] [Cited by in RCA: 2577] [Article Influence: 122.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 86. | Yeung F, Hoberg JE, Ramsey CS, Keller MD, Jones DR, Frye RA, Mayo MW. Modulation of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J. 2004;23:2369-2380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1942] [Cited by in RCA: 2188] [Article Influence: 104.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Zhao G, Ma H, Shen X, Xu GF, Zhu YL, Chen B, Tie R, Qu P, Lv Y, Zhang H. Role of glycogen synthase kinase 3β in protective effect of propofol against hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Surg Res. 2013;185:388-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Cui J, Li Z, Qian LB, Gao Q, Wang J, Xue M, Lou XE, Bruce IC, Xia Q, Wang HP. Reducing the oxidative stress mediates the cardioprotection of bicyclol against ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2013;14:487-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Chen CJ, Fu YC, Yu W, Wang W. SIRT3 protects cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress-mediated cell death by activating NF-κB. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;430:798-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Pellegrini L, Pucci B, Villanova L, Marino ML, Marfe G, Sansone L, Vernucci E, Bellizzi D, Reali V, Fini M. SIRT3 protects from hypoxia and staurosporine-mediated cell death by maintaining mitochondrial membrane potential and intracellular pH. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1815-1825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Cheng Y, Ren X, Gowda AS, Shan Y, Zhang L, Yuan YS, Patel R, Wu H, Huber-Keener K, Yang JW. Interaction of Sirt3 with OGG1 contributes to repair of mitochondrial DNA and protects from apoptotic cell death under oxidative stress. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Yang H, Yang T, Baur JA, Perez E, Matsui T, Carmona JJ, Lamming DW, Souza-Pinto NC, Bohr VA, Rosenzweig A. Nutrient-sensitive mitochondrial NAD+ levels dictate cell survival. Cell. 2007;130:1095-1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 780] [Cited by in RCA: 797] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Kim HS, Patel K, Muldoon-Jacobs K, Bisht KS, Aykin-Burns N, Pennington JD, van der Meer R, Nguyen P, Savage J, Owens KM. SIRT3 is a mitochondria-localized tumor suppressor required for maintenance of mitochondrial integrity and metabolism during stress. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:41-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 603] [Cited by in RCA: 643] [Article Influence: 42.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Allison SJ, Milner J. SIRT3 is pro-apoptotic and participates in distinct basal apoptotic pathways. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2669-2677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Shi T, Fan GQ, Xiao SD. SIRT3 reduces lipid accumulation via AMPK activation in human hepatic cells. J Dig Dis. 2010;11:55-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Purushotham A, Schug TT, Xu Q, Surapureddi S, Guo X, Li X. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of SIRT1 alters fatty acid metabolism and results in hepatic steatosis and inflammation. Cell Metab. 2009;9:327-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 912] [Cited by in RCA: 881] [Article Influence: 55.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Raval AP, Dave KR, Pérez-Pinzón MA. Resveratrol mimics ischemic preconditioning in the brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1141-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Nadtochiy SM, Redman E, Rahman I, Brookes PS. Lysine deacetylation in ischaemic preconditioning: the role of SIRT1. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;89:643-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Rane S, He M, Sayed D, Vashistha H, Malhotra A, Sadoshima J, Vatner DE, Vatner SF, Abdellatif M. Downregulation of miR-199a derepresses hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and Sirtuin 1 and recapitulates hypoxia preconditioning in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2009;104:879-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 489] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Yan W, Fang Z, Yang Q, Dong H, Lu Y, Lei C, Xiong L. SirT1 mediates hyperbaric oxygen preconditioning-induced ischemic tolerance in rat brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:396-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Zaouali MA, Ben Mosbah I, Boncompagni E, Ben Abdennebi H, Mitjavila MT, Bartrons R, Freitas I, Rimola A, Roselló-Catafau J. Hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha accumulation in steatotic liver preservation: role of nitric oxide. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3499-3509. [PubMed] |