INTRODUCTION

Bouveret’s syndrome is a rare complication of cholelithiasis that was first reported and named by Bouveret in 1896; this condition comprises a series of syndromes caused by a gastric outflow obstruction due to the migration of gallstones to the pylorus and duodenum via a gallbladder-duodenal fistula[1]. We have only rarely encountered this condition in clinical work, and few cases have been reported in the literature. The most common site of gallstone-induced ileus is the terminal ileum, followed by the proximal ileum and jejunum; only 1%-3% of cases occur in the duodenum, and an obstruction caused by incarcerated stones in the pylorus and duodenal bulb is the rarest form encountered in the clinical setting[2]. Gallstone-induced ileus is 3 to 16 times more common in females than in males, and Bouveret’s syndrome predominately affects older women[3]. Because it often presents in the elderly and with multiple comorbidities, it is associated with a high rate of mortality. The first treatment choice for this syndrome remains debatable.

CASE REPORT

A 55-year-old male was admitted to the hospital with a 2-wk history of upper abdominal distension and vomiting. Nausea and vomiting frequently occurred 4-5 h after a meal. Undigested food was sometimes present in the vomitus. Pain, fever, jaundice and melena were not reported by the patient. Several assays were performed in the outpatient department; the results of the blood analysis, urine analysis, amylase test and lipase test were normal. The patient had experienced a duodenal ulcer 20 years prior. There was a history of acute epigastric pain due to acute cholecystitis and gallbladder stone during the previous year. The pain was relieved by anti-inflammation treatment, and no surgery was performed.

Physical examination revealed mild tenderness in the epigastric area. Succession splash and Murphy’s sign were negative. Bowel sounds were normal. Gastroscopy was arranged for the following day and indicated that chyme could be observed in the gastric antrum and duodenal bulb. A large yellowish-brown hard stone was observed in the duodenal bulb, and a 1.2-cm-wide ulcer was located on the greater curvature side of the bulb. The diagnosis of gastric retention, gastrolithiasis and duodenal bulb ulcer was considered based on the medical history and gastroscopy results. The symptoms, including abdominal distension, nausea and vomiting, were quickly alleviated following a therapy of liquid diet, antacid, gastric mucosa protectant and supportive treatment and litholytic therapy with oral sodium bicarbonate solution.

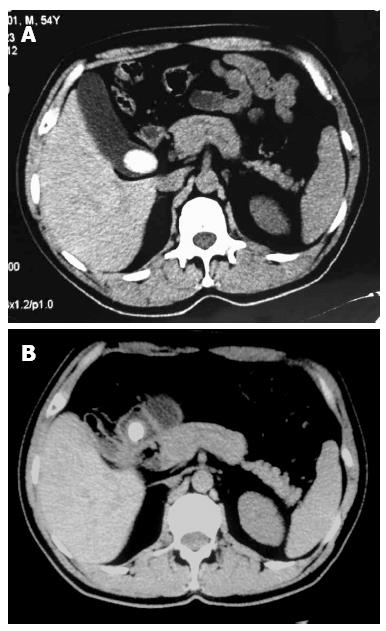

However, on the third day after admission, computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed a thick gallbladder wall and the presence of gas shadows in the gallbladder. The choledoch was slightly wider, and the walls of the gallbladder and the pylorus were indistinct from each other. Additionally, a calcified mass of approximately 2 cm in diameter was observed in the pylorus. A comparison to the CT scan from one year prior (Figure 1A) revealed an inflammatory perforation of the gallbladder and pylorus, the presence of an internal fistula and the migration of the gallstone from the gallbladder to the pylorus (Figure 1B). The upper gastrointestinal contrast also revealed a large round filling defect with a smooth border in the descending part of duodenum. Therefore, a revised diagnosis of Bouveret’s syndrome was made. The patient was transferred to the laparoscopic ward and underwent duodenotomy for gallstone removal, duodenal fistulation and subtotal cholecystectomy using a laparoscope. During the operation, multiple adhesions among the gallbladder, duodenal bulb and omentum were observed. After the adhesions were released, the gallbladder-duodenal fistula could be seen. A large stone with a diameter of approximately 3.0 cm × 4.0 cm was located below the fistula-duodenal opening. After making an incision in the gallbladder wall, it was observed that the cystic duct and sinus crossings had closed. Subsequently, duodenum incision, stone removal, placement of a drainage tube into the duodenum incision and interrupted suture were performed to close the duodenum. A subtotal cholecystectomy was also performed simultaneously. After postoperative hemostatic and anti-inflammatory treatment, the patient was discharged. Three weeks later, the patient was readmitted to remove the duodenal drainage tube. On the next day after the removal, fever and abdominal pain were observed. However, an abdominal CT revealed no obvious abnormalities. After a 5-d controlled diet and anti-inflammatory treatment, the patient recovered and was discharged without further incident.

Figure 1 Abdominal computed tomography.

A: Revealing a large calcified mass in the gallbladder (one year prior); B: Indicating the migration of the large stone from the gallbladder to the pylorus and gas shadows seen in the gallbladder (this time).

DISCUSSION

A gastric outlet obstruction caused by the migration of large gallstones to the pylorus and duodenum via a gallbladder-duodenal fistula, Bouveret’s syndrome, is a special type of gallstone-induced ileus that comprises only 1%-3% of cases[2,4]. This syndrome is extremely rare and appears predominately in older women, at an average age of 74.1 years[2]. Most of these patients experience complications, such as hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or other systemic diseases. Bouveret’s syndrome presents with the common symptoms of abdominal distension; abdominal pain; nausea; vomiting; fever; and occasionally gastrointestinal hemorrhage, such as hematemesis or melena[5,6]. Abdominal CT, upper gastrointestinal imaging and endoscopy offer important diagnostic value for diagnosing the disease[7,8]. In this case, the patient was a middle-aged male, rather than a member of the susceptible population, who presented the main manifestations, including abdominal distension, nausea, vomiting undigested food and a past history of duodenal bulb ulcer. As a result, his condition was easily misdiagnosed as duodenal bulb ulcer and pyloric obstruction. After a foreign body was observed in the duodenal bulb through endoscopy, gastrolithiasis was suspected. However, several doubts remained. First, there was no clear predisposition for gastrolith. Second, the foreign body was too large to have passed through the pylorus to arrive at the duodenum. Based on these doubts surrounding the diagnosis, the patient was submitted to further examination during litholytic and acid suppression therapy. The diagnosis was suddenly clearer based on the results of an abdominal CT. Compared with a CT image of the patient taken one year prior, it was apparent that the original large gallstone near the neck of the gallbladder had disappeared, and the gallbladder had shrunk with some gas remaining in it and a gallstone shadow in the pyloric cavity next to the gallbladder. These abdominal CT results suggested that the endoscopic finding was not a gastrolith but rather that the gallstone had penetrated into the duodenal bulb. Consequently, Bouveret’s syndrome was diagnosed. Upper gastrointestinal imaging results further supported the diagnosis. The treatment choice for Bouveret’s syndrome remains debatable and can include endoscopic treatment, extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy, intracorporeal electrohydraulic lithotripsy, surgery and laparoscopic treatment[9]. Currently, 1-stage or 2-stage surgery is often adopted[10-12]. One-stage surgery refers to a combination of enterolithotomy plus cholecystectomy and fistula repair within a single surgery. Two-stage surgery entails dividing the enterolithotomy and cholecystectomy into two operations. However, surgery is often associated with significant postoperative complications and mortality[3,13]. With the development of laparoscopic and other minimally invasive techniques, the successful application of laparoscopic treatment as a therapy for Bouveret’s syndrome has also been reported[14,15]. In this case, subtotal cholecystectomy, duodenotomy for gallstone removal and duodenal fistulation using a laparoscope were performed, taking into account the large size of the stones, the good general condition of the patient, the closed gallbladder and the duodenum fistula. The patient recovered and was discharged quickly. After the duodenal drainage tube was unplugged, no duodenal fistula was observed, and the condition of the patient remained stable after being followed up for 6 mo. The present case included the following features: (1) The patient was middle-aged, had no chronic systemic disease and did not belong to the usual susceptible population of Bouveret’s syndrome; (2) The clinical symptoms were atypical, with neither infection nor abdominal pain. The onset was similar to that of peptic ulcer and pyloric obstruction, which was initially suspected as gastrolithiasis; (3) Imaging data from one year prior provided an important basis to observe the evolution of the disease and make a diagnosis; and (4) Based on the condition of the patient, disposable laparoscopic lithotomy and cholecystectomy were conducted. The effect was satisfactory, and there were no obvious postoperative complications.

In conclusion, Bouveret’s syndrome is a rare cause of gastric outflow obstruction and is easily misdiagnosed. Therefore, when a patient presents an outbreak of symptoms that are similar to pyloric obstruction with a previous history of gallbladder stones, the clinician should consider Bouveret’s syndrome, which can be differentially diagnosed through a combination of endoscopy and abdominal imaging. As laparoscopic technology gradually matures, the advantages of the laparoscopic treatment of this syndrome have been realized in recent years. Laparoscopic enterolithotomy is safe and effective, with good patient tolerability, rapid postoperative recovery and few wound-related complications.