CASE REPORT

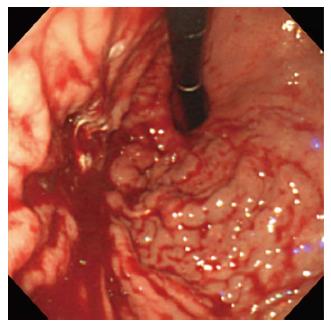

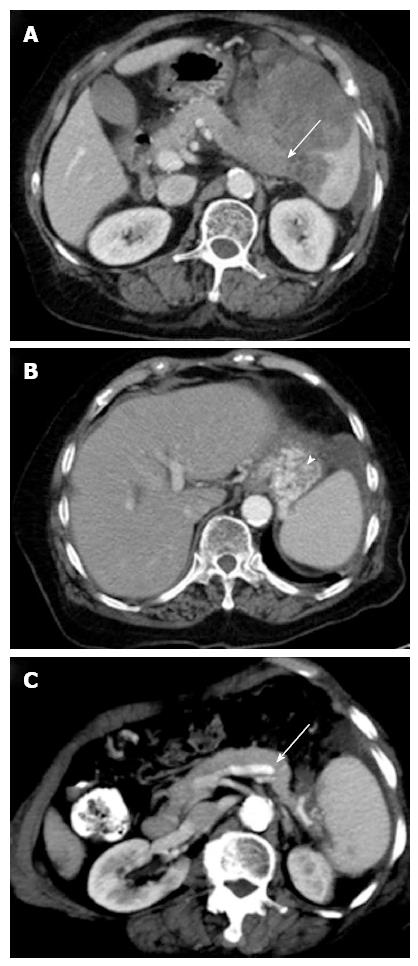

A 77-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital due to two episodes of bloody vomitus and three episodes of tarry stool. She did not have a significant medical or surgical history or any known allergies, nor was she taking any medication. The physical examination revealed pale conjunctiva without any jaundice, lymphadenopathy, or pedal edema. An abdominal palpation demonstrated an enlarged spleen, palpable below the left costal margin, and a digital rectal examination showed melena. The remainder of the patient’s systemic examination results was unremarkable. The blood pressure was 97/55 mmHg, the pulse rate was 96/min, the hemoglobin level was 8.9 g/dL, the platelet count was 118000/μL, and the stool occult blood test was positive. The patient’s biochemistry tests, including those for liver and renal function, were within the normal limits, apart from a high serum lactate dehydrogenase level (1112 U/L). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy demonstrated an isolated gastric varices (IGV) at the cardia and high body of the stomach, with active bleeding (Figure 1); thus, sclerotherapy with cyanoacrylate was successfully performed. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a large mass in the enlarged spleen, with near total occlusion of the splenic vein (Figure 2A). This splenic vein occlusion led to the development of a gastric varices at the fundus (Figure 2B), and the portal and superior mesenteric veins were patent. The laboratory findings indicated the patient’s carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 levels were normal.

Figure 1 Engorged varices at the cardia and high body of the stomach, with active bleeding.

Figure 2 Imaging findings.

A: Axial contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) at the level of the splenic hilum shows a large low-attenuation mass in the enlarged spleen. The mass involves the splenic vein with near total occlusion (arrow); B: The development of a gastric varice (arrowhead) at the fundus; C: The 6-mo follow-up CT shows that the splenic mass has almost completely resolved, allowing the splenic vein (arrow) to return to patency.

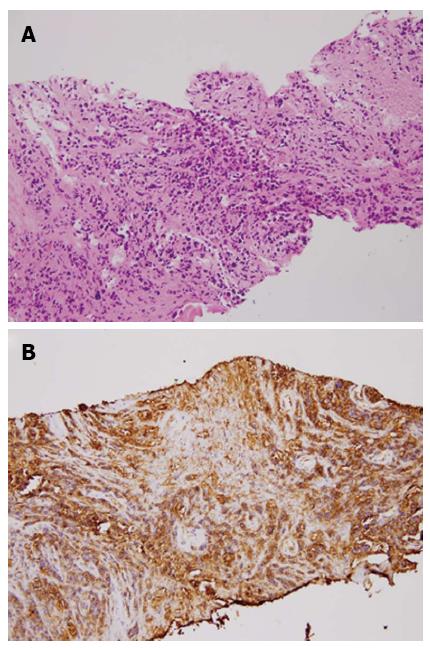

The patient underwent ultrasound-guided aspiration biopsy, and histopathology confirmed a high-grade B-cell lymphoma (Figure 3). Thereafter, the patient received chemotherapy with a cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin, and prednisolone (CHOP) regimen, and the splenic vein occlusion resolved after the lymphoma regressed (Figure 2C).

Figure 3 Pathologic findings (hematoxylin/eosin staining) and immunohistochemical staining.

A: The predominant fibrous tissue with necrotic foci and scattered atypical cells characterized by pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nuclei with discohesive arrangement. B: The B-lymphocyte marker (CD20) was strongly positive in the atypical cells.

DISCUSSION

IGVs are observed in up to 5% of patients with cirrhosis and in up to 10% of patients with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension[1]. Such varices can occur in patients with segmental or left-sided portal hypertension (LSPH), and the incidence has increased over the past three decades because of increased awareness of the entity and advances in diagnostic approaches[2,3]. When a segment of the portal venous bed is obstructed, varices can develop in the area to decompress the blocked segment. In cases of segmental portal hypertension, the blood drains in a retrograde manner through the short and posterior gastric veins and the gastroepiploic veins. This process results in blood flow and a pressure increase, which causes dilation of the submucosal structures, leading to the formation of a gastric varice[4].

LSPH primarily occurs as a result of splenic vein obstruction, most commonly resulting from pancreatic disorders[5]. Because the splenic vein is posterior to the pancreas and in direct contact with it, any type of pancreatic disease, including cancer, pancreatitis, abscess formation, or a pseudocyst, can affect the splenic vein[6-8]. In a study by Moosa et al, pancreatitis, diagnosed by either biopsy or surgery, was part of the LSPH etiology in 87 (60%) of 144 cases, while pancreatic malignancy was detected in only 13 (9%) patients[9,10]. Various disorders other than pancreatic diseases, such as partial gastrectomy, metastatic carcinoma, retroperitoneal fibrosis, or protein S deficiency, have a wide spectrum of mechanisms involved in causing splenic vein occlusion[5,11-13]. Among the metastatic carcinomas, oat cell carcinoma[14], colon cancer[5], gastric cancer[5], renal cancer[12], and rare retroperitoneal liposarcoma[9] have been reported to cause splenic vein occlusion. Primary pancreatic lymphoma, with splenic vein thrombosis and IGV bleeding, has been reported as well[15]. Our patient had a rare case of splenic B-cell lymphoma that caused splenic vein occlusion and IGV bleeding.

In general, IGVs are asymptomatic and identified incidentally. In symptomatic cases, the most common clinical manifestation is gastrointestinal bleeding from ruptured gastric varices; statistically, 45%-72% of patients with LSPH present with the above-mentioned symptom[3]. Splenomegaly and abdominal pain are observed in 71% and 25%-38% of patients with LSPH, respectively[5,9], whereas ascites seldom develop[16]. Various radiological examinations can assist in making an IGV diagnosis, including upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, angiography, ultrasonography, contrast-enhanced CT portography, and magnetic resonance imaging. In one study, gastric varices could be accurately diagnosed and localized in nearly 90% of cases by endoscopy[17]. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) appears to be a more accurate test than transabdominal ultrasonography, which is useful for evaluating the pancreatic parenchyma and splenic vasculature[18]. Contrast-enhanced CT portography can quickly elucidate the portal venous system, but it requires a large amount of iodinated contrast material. Magnetic resonance angiography with gadopentetate dimeglumine is a promising noninvasive test that is being increasingly used to diagnosis patency or thrombosis of the portal venous system[19].

The treatment of IGV bleeding should be directed toward the splenic side of the portal circulation because the pressure increases only on that side[14]. Several choices such as conservative therapy (e.g., pharmacotherapy, balloon tamponade, endoscopic therapy with sclerotherapy or band ligation) and interventional radiologic techniques, are available for bleeding control. Japanese endoscopists have reported using a combination technique of endoscopic variceal ligation injection sclerotherapy to treat acute gastric varice bleeding; when using this procedure, the rebleeding rate was low (0%-8%), the gastric varice eradication rate was 85% at up to 2 years post-treatment, and hemostasis was achieved in 100% of patients[20]. Transcatheter splenic artery embolization has also been attempted with varying degrees of success, but it has not become a preferred approach. If a patient with active bleeding is unresponsive to conservative management, then splenectomy is indicated. A large splenectomy series that included patients with isolated splenic vein thrombosis showed that none of the patients had recurrent bleeding during the 11-mo mean follow-up period after splenectomy[9].

The current case was a rare incidence of IGV bleeding induced by splenic lymphoma-associated splenic vein occlusion. In this patient, chemotherapy was an alternative treatment for splenic vein occlusion caused by chemotherapy-sensitive tumors. Our patient responded well to chemotherapy, and the splenic vein occlusion resolved after the lymphoma regressed.