Published online Oct 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6931

Revised: July 1, 2013

Accepted: August 4, 2013

Published online: October 28, 2013

Processing time: 164 Days and 4.4 Hours

The use of weight reduction surgeries has increased over the years with a higher proportion of these surgeries being sleeve gastrectomies, this has been associated with some complications including staple line leaks. We report a 32-year-old male who had undergone a laparoscopic gastric band surgery and subsequently a laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, this was complicated by both an staple line leak at the gastroesophageal junction as well as a large (> 4 cm) posterior gastric wall defect due to gastric wall necrosis. We used two co-axially inserted self-expandable stents (SEMS) in the management of this patient, 5 stents were used over repeated endoscopy sessions and 20 wk. Both defects had resolved without the need for surgical intervention.This is the first reported case were SEMS are used for both a staple line leak as well as a gastric wall defect. We also review the literature on the use of SEMS in the management of leaks post weight reduction surgeries.

Core tip: Management of staple line leaks has incorporated, in recent years, a non-surgical approach which mainly depends on elimination of oral intake, parenteral nutrition, antimicrobial therapy, and drainage procedures and more recently the use of esophageal self-expandable metal stents for sealing of these leaks as well as the induction of tissue hyperplasia that would close these leaks. This case is the first, to our knowledge, that reports the successful use of self-expandable metal stents for the closure of a posterior gastric wall necrosis as a consequence of repeated bariatric surgery.

- Citation: Almadi MA, Aljebreen AM, Bamihriz F. Resolution of an esophageal leak and posterior gastric wall necrosis with esophageal self-expandable metal stents. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(40): 6931-6933

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i40/6931.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6931

The morbidity and mortality associated with obesity has been well recognized and in some clinical settings the method to curtail such an epidemic is via weight reduction surgeries, such an intervention is associated with some complications of which surgical leaks are one of the most unfavorable as they are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality[1]. The management of these complications has evolved from surgical reintervention to a more conservative approach with elimination of oral intake, parenteral nutrition, antimicrobial therapy, and drainage[1]. A more recent trend has been to use esophageal self-expandable metal stents (SEMS) or self-expandable plastic stents (SEPS)[1] as a method of occluding these leaks. We present an unusual case where SEMS were used in the management of a patient who developed both a staple line leak at the gastroesophageal junction as well as necrosis of the posterior gastric wall.

A 32-year-old male was referred to our institution with a diagnosis of an esophageal leak after a laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG). The patient had already undergone a laparoscopic gastric band weight reduction surgery about 5 years before his presentation with a suboptimal weight loss reduction. Subsequently the patient underwent a LSG and in the first postoperative week the patient developed clinical signs of an enteric leak with the development of tachycardia as well as fever.

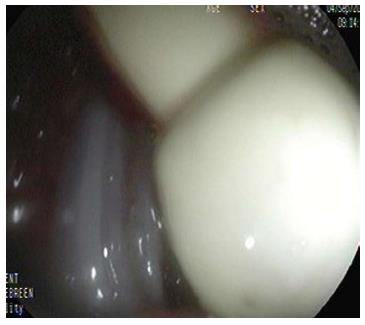

A barium swallow demonstrated a leak at the level of the distal end of the esophagus and a computerized tomography (CT) demonstrated a fluid collection close to the surgical bed. The patient was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics and oral intake was stopped. An endoscopic line of management was planned and an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed and demonstrated an opening in the distal esophagus that corresponded to the leak seen on a barium study, distal to that defect the pouch above the gastric band was seen and a large defect was seen in the posterior wall of the stomach remnant, which through fluid and the drains left post surgery could be seen (Figures 1 and 2). A single A 12 cm fully-covered SEMS, Niti-S (Taewong Medical, Seoul, South Korea), was deployed with the proximal end of the stent left above the level of the leak and the distal end was just proximal to the pylorus.

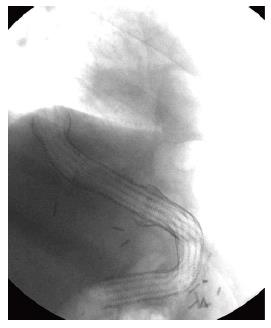

A month latter the patient presented with nausea and vomiting and the stent was found to have migrated, a repeat EGD found that the distal end of the SEMS caused an ulcer in the antrum of the stomach, The stent was removed and the patient was kept on a proton pump inhibitor and 12 d later two 15 cm long partially covered SEMS, Ultraflex (Microvasive, Boston Scientific, United States), were deployed in a co-axial fashion, the proximal end of the first stent lied at 30 cm from the incisors above the level of the leak while the distal end of the second stent lied in the duodenum (Figure 3). A few days after the procedure the patient was started on a liquid diet and subsequently the output from the drains had stopped. After 11 and half weeks a rat-tooth forceps was used for removing both stents but the defects in the lower esophagus and the stomach were still present although they had decreased substantially in size, another two partially covered SEMS esophageal stents (Ultraflex) were inserted in a similar fashion to the initial insertion. After 4 wk both stents were removed easily (Figure 4) and the defects had resolved. The patient had a subsequent CT scan of the abdomen with oral contrast that demonstrated resolution of both leaks and the drains were removed.

The use of enteric stents has evolved from the management of malignant diseases to benign strictures as well as leaks. LSGs are complicated by leaks in 2.2%[3]-2.4%[4] of cases based on two systematic reviews with the majority of these leaks (85%-89%) being located in the proximal third of the stomach near the gastroesophageal junction[1,4] and are associated with a non-trivial mortality rate (6%-14.7%)[1]. The management options for this complication vary from repeat surgery to a more conservative management with an attempt to seal these leaks through enteric stenting. Surgical management has been associated with a high morbidity (up to 50%) and mortality (2%-10%)[1], as a result, initial management has moved towards a more conservative endoscopic treatment. Although there are no randomized controlled trials to assess the efficacy of this approach, a systematic review that included 25 studies, incorporating 267 patients showed that the success rate with the use of SEMS was about 85% with no difference in the rate of clinical success between the type of SEMS used weather they were partially or fully-covered SEMS or SEPS (P = 0.97)[5], of note this systematic review included cases who had esophageal anastomotic leaks or a benign rupture of the esophagus[5]. A second meta-analysis for patients who exclusively had leaks post bariatric surgery and were managed by stenting found a success rate of 87.8% (95%CI: 79.4%-94.2%)[6].

The case we present is unique due to the simultaneous presence of a leak at the gastreosophageal junction as well as a large area of necrosis in the posterior wall of the stomach both of which were eliminated using SEMS for a prolonged period of time and the use of a total of 5 stents and five endoscopy sessions spanning a period of 20 wk. SEMS are usually kept in place on average for 6 wk[5]. In the case reported the duration of stenting was 20 wk mainly due to the large defect seen in the gastric wall.

Stent migration occurred with the first fully covered SEMS that necessitated its removal and exchange. This complication is acceptable as the rate of migration in general in a meta-analysis was 16.9% (95%CI: 9.3%-26.3%)[6] and van Boeckel et al[5] found that fully covered SEMS had a higher migration rate when compared to partially covered SEMS (26% vs 12% respectively, P≤ 0.001)[5]. Although endoscopic repositioning/removal might suffice in the majority of cases, as in our case, some of these stents passed per-rectum spontaneously or had to be removed surgically[6].

The longer the SEMS are left in place the higher the risk of ingrowth of tissue within the stent and subsequently the more difficult its removal[1]. Removal of these SEMS usually require the insertion of a SEPS within the SEMS to induce ingrowth tissue necrosis and after a few days both the SEMS and SEPS can be removed, successful removal of the SEMS after leak closure is 91.6% (95%CI: 84.2%-96.8%)[6]. We intentionally removed the SEMS after predefined durations to reduce the risk of failure to remove the SEMS. Furthermore, due to the initial use of fully covered and then partially covered SEMS they were removed without requiring the insertion of SEPS.

This case is the first to our knowledge where both a staple line leak post LSG and posterior gastric wall necrosis were simultaneously treated using SEMS without the need for repeated surgery.

P- Reviewer Regimbeau JM S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Kumar N, Thompson CC. Endoscopic management of complications after gastrointestinal weight loss surgery. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:343-353. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Márquez MF, Ayza MF, Lozano RB, Morales Mdel M, Díez JM, Poujoulet RB. Gastric leak after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1306-1311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Parikh M, Issa R, McCrillis A, Saunders JK, Ude-Welcome A, Gagner M. Surgical strategies that may decrease leak after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 9991 cases. Ann Surg. 2013;257:231-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Aurora AR, Khaitan L, Saber AA. Sleeve gastrectomy and the risk of leak: a systematic analysis of 4,888 patients. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1509-1515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 427] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 31.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | van Boeckel PG, Sijbring A, Vleggaar FP, Siersema PD. Systematic review: temporary stent placement for benign rupture or anastomotic leak of the oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1292-1301. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Puli SR, Spofford IS, Thompson CC. Use of self-expandable stents in the treatment of bariatric surgery leaks: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:287-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |