Published online Oct 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6849

Revised: August 13, 2013

Accepted: September 13, 2013

Published online: October 28, 2013

Processing time: 190 Days and 10.1 Hours

AIM: To investigate the effect of antiviral therapy with nucleoside analogs in hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related cirrhosis and esophageal varices.

METHODS: Eligible patients with HBV-related cirrhosis and esophageal varices who consulted two tertiary hospitals in Beijing, China, the Chinese Second Artillery General Hospital and Chinese PLA General Hospital, were enrolled in the study from January 2005 to December 2009. Of 117 patients, 79 received treatment with different nucleoside analogs and 38 served as controls. Bleeding rate, change in variceal grade and non-bleeding duration were analyzed. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression was used to identify factors related to esophageal variceal bleeding.

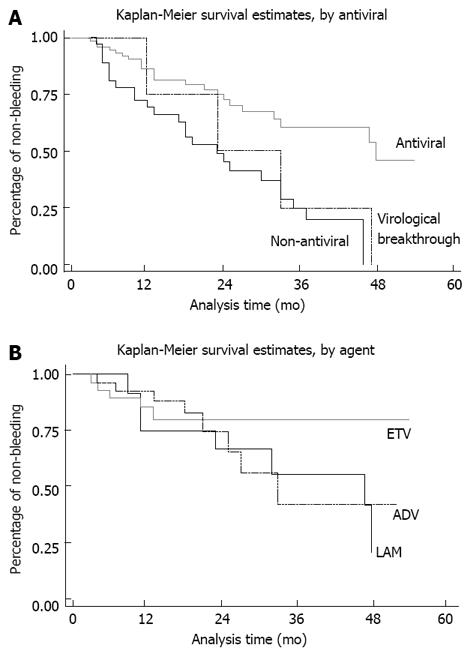

RESULTS: The bleeding rate was decreased in the antiviral group compared to the control group (29.1% vs 65.8%, P < 0.001). Antiviral therapy was an independent factor related to esophageal bleeding in multivariate analysis (HR = 11.3, P < 0.001). The mean increase in variceal grade per year was lower in the antiviral group (1.0 ± 1.3 vs 1.7 ± 1.2, P = 0.003). Non-bleeding duration in the antiviral group was prolonged in the Kaplan-Meier model. Viral load rebound was observed in 3 cases in the lamivudine group and in 1 case in the adefovir group, all of whom experienced bleeding. Entecavir and adefovir resulted in lower bleeding rates (17.2% and 28.6%, respectively) than the control (P < 0.001 and P = 0.006, respectively), whereas lamivudine (53.3%) did not (P = 0.531).

CONCLUSION: Antiviral therapy delays the progression of esophageal varices and reduces bleeding risk in HBV-related cirrhosis, however, high-resistance agents tend to be ineffective for long-term treatment.

Core tip: Antiviral therapy with nucleoside analogs improves clinical outcome in hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related decompensated cirrhosis. However, the emergence of resistance results in liver injury. The consequences may be worse in patients with esophageal varices (EV), in which bleeding and death often occur. This study evaluated the efficacy of antiviral treatment over 5 years in patients with HBV-related cirrhosis and EV and found that antiviral therapy decreased the risk of bleeding. However, agents with a high rate of virological breakthrough were ineffective in preventing bleeding. These findings provide evidence-based suggestions for the treatment of this special group of patients.

- Citation: Li CZ, Cheng LF, Li QS, Wang ZQ, Yan JH. Antiviral therapy delays esophageal variceal bleeding in hepatitis B virus-related cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(40): 6849-6856

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i40/6849.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6849

Liver cirrhosis is a common disease that poses a serious threat to the health of patients, and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is one of the main causes of cirrhosis. The 5-year survival rate of decompensated liver cirrhosis is reported to be only 14%-28%[1,2]. Nucleoside analogs, by inhibiting HBV polymerase and decreasing HBV load, have been widely used in the treatment of hepatitis B. Antiviral therapy with sustained suppression of viral replication has shown benefits in decompensated cirrhotic patients. However, there are no detailed reports of the effects of antiviral therapy in esophageal variceal bleeding, one of the most dangerous and life-threatening complications of cirrhosis.

About 30% of patients with cirrhosis and esophageal varices (EV) will experience bleeding during their lifetime[3]. A single episode of uncontrolled variceal bleeding results in immediate death in 5%-8% of patients and has a six-week mortality rate of at least 20%[4]. Therefore, prevention of variceal bleeding is of paramount importance.

A number of studies have shown that antiviral therapy with nucleoside analogs is associated with improved clinical outcome in patients with HBV-related decompensated cirrhosis[5,6]. However, the problem of drug resistance has also emerged with the long-term use of these agents[7,8]. The emergence of resistance results in a loss of virological suppression, which in turn causes progressive liver injury and even severe liver failure[9]. The consequences may be worse in patients with EV. Virological breakthrough in patients with EV usually results in EV bleeding or even death.

A retrospective study by Koga et al[10] demonstrated an improvement in patients with esophageal varices following lamivudine (LAM) treatment. However, the study consisted of only 12 patients treated with LAM and 6 controls, and there were no data on bleeding rate and the effect of virological breakthrough. As patients usually experience bleeding when virological breakthrough takes place, it is necessary to separate the patients and evaluate the harm of drug resistance and the benefit of HBV suppression in these patients to provide evidence-based treatment suggestions. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy of antiviral treatment over 5 years in patients with HBV-related cirrhosis and EV.

This study evaluated the efficacy of antiviral therapy with different nucleoside analogs in patients with HBV-related cirrhosis and EV. Eligible patients with HBV-related cirrhosis who consulted two tertiary hospitals in Beijing, China, the Chinese Second Artillery General Hospital and Chinese PLA General Hospital, were enrolled in the study from January 2005 to December 2009.

The study population had HBV-related cirrhosis and EV. All patients had serum HBV DNA > 500 copies/mL as measured by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Fluorescence Quantitation kit; Shanghai Kehua Bio-engineering, Shanghai, China). Exclusion criteria included: history of hepatitis C or D, viral hepatitis, evidence of alcoholic cirrhosis, history of surgery for portal hypertension (splenectomy, shunt or devascularization), suspected liver cancer, hepatic encephalopathy or hepatorenal syndrome, or life-threatening diseases.

In accordance with clinical practice guidelines[11-13], endoscopic eradication of varices was performed in cases with a history of bleeding. Other treatment modalities, such as polyene phosphatidylcholine, reduced glutathione and diuretics, were administered as required. Propranolol was prescribed to all patients except for those who could not tolerate, or had contraindications to, beta-blocker use.

Because no evidence-based suggestions on antiviral therapy in patients with esophageal varices were available, the benefit and potential harm (such as drug resistance and adverse effects) of antiviral therapy were introduced to the patients. Patients received one of the following antiviral treatments immediately after enrollment: lamivudine (LAM) (100 mg/d, Glaxo Wellcome, United Kingdom), adefovir (ADV) (10 mg/d, Tianjin Pharmaceutical, China), entecavir (ETV) (0.5 mg/d, Bristol-Myers Squibb, United States), telbivudine (LdT) (600 mg/d, Novartis, Switzerland), a combination of LAM and ADV (LAM 100 mg/d + ADV 10 mg/d), or no antiviral therapy according to their wishes. As antiviral therapy may have a greater risk in patients with esophageal varices, it was not prescribed if the patients refused it for reasons such as adverse effects and resistance.

The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of both Hospitals. All patients provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study.

Patients were followed up at a 3-mo interval over 5 years, and levels of HBV DNA, glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (GPT), glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT), total bilirubin, serum albumin, prothrombin time, platelet count, diameter of portal vein and splenic area on ultrasound scan were recorded.

Endoscopic findings were graded according to the criteria of the Japanese Association of Portal Hypertension[14] as Grade I, II or III, and given a score of 1, 2 or 3, respectively. Bleeding was scored as 4. Patients whose varices were eradicated were scored as 0. Those who showed newly visible, small vessels after endoscopic eradication, but did not reach grade I were scored as 0.5. Patients without a history of bleeding underwent endoscopic examination every 2 follow-up visits (at a 6-mo interval). Cases with a history of bleeding underwent endoscopic eradication of the varices and follow-up at month 3, and then at a 6-mo interval over the remaining study period. Variceal scores were recorded.

The end-point of this observational study was bleeding or time to study conclusion (December 2009) if the patient did not experience any bleeding. The duration from study enrollment to bleeding or to study conclusion was defined as non-bleeding duration.

The incidence of adverse events, discontinuations and deaths were documented. Complete blood counts, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, creatine kinase, lactic acid and electrolytes were also monitored.

The software STATA 10.0 (Stata Corporation, United States) was used in the statistical analysis of data. The bleeding rates (defined as the cumulative proportion of patients who experienced an esophageal variceal bleeding episode during the study) in the antiviral and control groups were compared using the χ2 test. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression was used to identify factors related to esophageal variceal bleeding. Non-bleeding duration of the different groups was determined using the Kaplan-Meier model. Increases in variceal score were compared between groups using the Student’s t test. The portal vein diameter and splenic area on ultrasound scan, levels of GPT, GOT, total bilirubin, serum albumin, prothrombin time and platelet counts were also compared using the Student’s t test. All tests were two-sided and a P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 117 patients who fulfilled the study criteria were enrolled from January 2005 to December 2009. Of these, 79 patients received antiviral therapy, including ETV (n = 29), ADV (n = 28), LAM (n = 15), LdT (n = 4) and combination treatment with LAM and ADV (n = 3). Patients not receiving antiviral therapy (n = 38) were followed up as a control group, and received the same treatment as the antiviral group minus antiviral therapy. Of the total study population, 63 patients (42 in the antiviral group and 21 in the control group) who had a history of bleeding underwent endoscopic eradication of varices, while the other 54 cases (37 in the antiviral group and 17 in the control group) without a history of esophageal variceal bleeding did not undergo endoscopic eradication treatment. Primary prevention was not performed in this study population. In addition, a total of 95 patients (65 patients in the antiviral group and 30 patients in the control group) received propranolol. Both propranolol and endoscopic eradication patterns were not significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.801 and P = 0.846, respectively). The antiviral treatment and control groups were well matched with regard to gender, age, hepatic function, grade of EV, HBV DNA level, HBeAg status, portal vein diameter and splenic section area on ultrasound (Table 1).

| Non- antiviral (n = 38) | Antiviral (n = 79) | P value | Normal range | |

| Gender (male/female) | 30/8 | 62/17 | 1.000 | |

| Age (yr) | 51.8 ± 10.3 | 50.4 ± 8.8 | 0.443 | |

| Median Child-Pugh score | 8 | 8 | 0.887 | |

| Previous grade of EV (0/1/2/3) | 21/0/6/11 | 41/4/18/16 | 0.330 | |

| Previous copies of HBVDNA (log10) | 4.2 ± 1.1 | 4.6 ± 2.5 | 0.176 | (-) |

| Previous hepatitis B e antigen (+/-) | 24/14 | 46/33 | 0.689 | (-) |

| Previous diameter of portal vein (mm) | 11.8 ± 2.1 | 12.6 ± 2.2 | 0.392 | < 10 |

| Previous splenic section area (cm2) | 35.3 ± 9.5 | 37.4 ± 13.2 | 0.384 | < 20 |

| GPT (IU/L) | 49.7 ± 21.1 | 53.3 ± 64.9 | 0.315 | 5-40 |

| GOT (IU/L) | 48.1 ± 32.8 | 57.9 ± 56.2 | 0.231 | 5-40 |

| TB (mmol/L) | 26.7 ± 14.6 | 25.1 ± 15.5 | 0.635 | 3.4-17.1 |

| ALB (g/L) | 24.7 ± 4.9 | 25.4 ± 5.0 | 0.667 | 35-50 |

| PT (s) | 14.9 ± 2.5 | 16.5 ± 7.9 | 0.236 | < 12 |

| PLT (1012/L) | 83.1 ± 41.8 | 78.7 ± 41.9 | 0.600 | 100-300 |

| Endoscopic eradication (yes/no) | 17/21 | 37/42 | 0.846 | |

| Propranolol (yes/no) | 30/8 | 65/14 | 0.801 |

By week 12 of treatment, HBV DNA decreased to undetectable levels (defined as < 500 copies/mL, by PCR) in 58 (73.4%) of the 79 patients in antiviral treatment group. This was observed in 23 (79.3%) patients in the ETV group, 19 (67.8%) patients in the ADV group, 12 (80.0%) patients in the LAM group, 2 patients in the Ldt group (n = 4) and 2 patients in the LAM/ADV treatment group (n = 3). The number of patients achieving undetectable HBV DNA levels increased to 67 at week 24. At week 48, a total of 71 patients in the antiviral group achieved undetectable HBV DNA levels. None of the patients in the control group (n = 38) achieved undetectable HBV DNA during the study.

The portal vein diameter and area of splenic section tended to increase at the conclusion of the study compared to baseline. However, there was a smaller mean increase in the diameter of the portal vein and area of splenic section on ultrasound in the antiviral group compared to the control group (Table 2). Analysis of biochemical profiles (alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, serum albumin, total bilirubin and prothrombin time) showed progressive improvements in liver function in the group receiving antiviral treatment (Table 2). Median Child-Pugh score increased from 8 to 10 in control patients (P = 0.018), and decreased from 8 to 7 in the antiviral group (P = 0.686).

| Non-antiviral | Antiviral | P value | |

| (n = 38) | (n = 79) | ||

| GPT (IU/L) | 19.2 ± 53.1 | -28.6 ± 58.8 | < 0.001 |

| GOT (IU/L) | 19.9 ± 52.8 | -34.9 ± 86.2 | 0.001 |

| TB (mmol/L) | 3.9 ± 9.6 | -3.8 ± 9.5 | 0.009 |

| ALB (g/L) | -2.8 ± 5.5 | 1.2 ± 6.1 | 0.003 |

| PT (s) | 1.4 ± 2.2 | -0.2 ± 2.1 | 0.001 |

| PLT (1012/L) | -18.9 ± 28.8 | -10.3 ± 16.9 | 0.029 |

| Diameter of portal vein (mm) | 1.0 ± 0.9 | 0.2 ± 0.8 | < 0.001 |

| Splenic section area (cm2) | 8.6 ± 7.2 | 3.6 ± 9.8 | 0.012 |

By the end of the study, the bleeding rate was significantly decreased in the antiviral group (n = 79) compared to the control group (n = 38) (29.1% vs 65.8%, P < 0.001). The bleeding rate was also statistically different when all the patients were stratified into the endoscopic eradication group and non-endoscopic intervention group (Table 3). The mean ± SD increase in variceal score was reduced in the antiviral treatment group compared with the control group (Table 3).

| Non-antiviral | Antiviral | P value | |

| All the cases (n = 117) | 1.7 ± 1.2 | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 0.003 |

| Endoscopic eradication (n = 63) | 1.8 ± 1.5 | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 0.098 |

| No endoscopic intervention (n = 54) | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 0.8 ± 0.9 | 0.003 |

Multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to identify the factors associated with increased or decreased esophageal bleeding. The results showed that antiviral therapy (OR = 11.3, 95%CI: 3.1-38.5; P < 0.001), endoscopic eradication of varices (OR = 15.8, 95%CI: 4.1-51.1; P < 0.001), baseline portal vein diameter (OR = 39.1, 95%CI: 1.6-842.6; P = 0.025) and baseline serum HBV DNA level (OR = 0.8, 95%CI: 0.6-1.1; P = 0.042) were independent factors related to esophageal bleeding.

Four cases showed undetectable HBV DNA initially, however, viral load rebound was observed during follow-up, which was defined as virological breakthrough. All 4 cases bled in contrast to other patients who benefited from antiviral therapy.

In the LAM group (n = 15), three cases were found to have virological breakthrough during the study. All 3 cases had no history of bleeding and therefore were not treated with endoscopy. In the first case, virological breakthrough was detected at week 48 (1.8 × 105 copies/mL) and ADV was administered immediately, however, the patient exhibited re-bleeding at week 53 and the HBV DNA level reached 3.3 × 105 copies/mL. In the second case, the patient bled at week 192 and eventually died due to bleeding. Examination revealed HBV DNA at 5.1 × 105 copies/mL. In the third case, the patient bled at week 90 and HBV DNA breakthrough was detected on examination (3.1 × 108 copies/mL). The patient was treated with vasoactive drugs, endoscopic eradication of varices and switched to ETV after cessation of bleeding. HBV DNA levels were subsequently undetectable at 12 wk after treatment, and the patient was bleed-free for 48 wk by the end of the study.

One patient in the ADV group (without a history of bleeding and endoscopic intervention) experienced bleeding at week 130. HBV DNA was 9.8 × 103 copies/mL at examination. The patient was switched to ETV after cessation of bleeding and was bleed-free for 36 wk by the end of the study.

As more cases suffered from virological breakthrough and bleeding, the bleeding rate in the LAM group was not statistically different from that in the control group (8/15 vs 25/38, P = 0.531), while the ETV (5/29) and ADV (8/28) groups showed a lower bleeding rate (P < 0.001 and P = 0.006, respectively) compared to the control group. ETV was statistically better than LAM (P = 0.019), and no significant differences were found between the other agents.

There was one case of bleeding in both the LdT (n = 4) and combination treatment (LAM/ADV) groups (n = 3), and due to the small number of cases, they were not included in the statistical analysis.

Kaplan-Meier analyses demonstrated that bleeding was postponed in the antiviral treatment group compared to the control group (Figure 1A). However, the curve of virological breakthrough cases was close to that of the control group (Figure 1A). The Kaplan-Meier curves of ETV, ADV and LAM crossed each other within the first 2 years, but deviated beyond the 2-year mark (Figure 1B).

One patient died of esophageal variceal bleeding as stated above; no other severe adverse events were reported in the study. Most reported side effects were mild such as fatigue (n = 1), headache (n = 1), dyspepsia (n = 2), nausea (n = 1), dizziness (n = 1) and insomnia (n = 1). Discontinuation of treatment due to adverse events was not observed.

In this study, follow-up ended if the patient bled. Additional follow-up was included to determine the effect of antiviral therapy on patient survival. The cumulative 1-year survival rate was 97.5% (77/79) and 89.5% (34/38) for the antiviral group and control group, respectively (P = 0.086). The cumulative 2-year survival rate was 93.7% (74/79) and 86.3% (29/38) for the antiviral group and control group, respectively (P = 0.012). However, 8 patients in the control group switched to antiviral therapy. When these 8 patients were excluded, the cumulative 2-year survival rate in the control group was 70.0% (21/30), which was also lower than in the antiviral group (P = 0.002). Most of the patients in the control group switched to antiviral therapy during the additional follow-up period, and a comparison of the 5-year survival rate of the control group and antiviral group was not available. In addition to the patient who died of drug resistance and bleeding, 17 patients died (9 due to bleeding, 3 due to hepatic encephalopathy, 2 due to chronic liver failure and 3 due to liver cancer) and 17 were lost during the additional follow-up in the antiviral group. The overall 5-year survival rate in the antiviral group was 71.0%, which was higher than in the general cirrhotic patients[1].

Esophageal variceal bleeding is a life-threatening complication of decompensated cirrhosis, and bleeding from varices is a medical emergency which requires immediate treatment. If bleeding is not controlled quickly, the patient may go into shock or die. Aside from the urgent need to stop the bleeding, treatment is also aimed at the prevention of future bleeding. Treating the underlying cause of variceal bleeding can help prevent recurrence and early treatment of liver disease may prevent the development of varices.

Propranolol is accepted as the main treatment modality for the prevention of esophageal variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients[15,16]. Preventive endoscopic intervention is advocated by some medical experts in high-risk cases. For patients who have experienced bleeding, the accepted modalities for the prevention of re-bleeding include endoscopic eradication of varices (secondary prophylaxis)[11-13], continuous administration of propranolol and regular endoscopic follow-up plus supplementary endoscopic intervention[17-19]. The present study examined the role of antiviral therapy as an additional option for the prevention of esophageal variceal bleeding in hepatitis B patients.

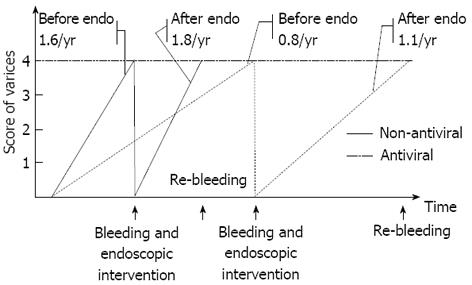

Nucleoside analog treatment in decompensated cirrhosis has been widely accepted in recent years[20-22], however, there have been no studies on the efficacy of antiviral treatment in patients with both cirrhosis and esophageal varices. In this study, antiviral therapy delayed progression of EV and decreased bleeding rates in cirrhotic patients with actively replicating HBV. Figure 2 shows the model of varices development. The grade of EV increases with time resulting in bleeding. After endoscopic eradication, the variceal score increases again until bleeding recurs. Antiviral therapy delayed both the progression of varices before and after endoscopic therapy and postponed esophageal variceal bleeding (i.e., effective in both primary and secondary prophylaxis).

The delayed progression of EV and decreased bleeding rates in patients receiving antiviral therapy may be explained by relief of portal hypertension. Decreased inflammation due to antiviral therapy might contribute to lower pressure of hepatic sinusoids. In addition, it has been reported that long-term antiviral therapy can lead to histological improvement of cirrhosis, slowing the rate of deterioration[23]. Although biopsy of the liver was not performed in this study, the improvement in liver structure was reflected by the delayed dilation of portal veins, delayed increase in spleen size, the reversion of levels of GPT, GOT, bilirubin, prothrombin time, albumin and delayed decrease in platelets count. These clinical benefits, together with delayed bleeding, are the ultimate aims in clinical practice. Recently, an on-line published study reported that ETV therapy reduced the risks of hepatic events in hepatitis B cirrhosis patients within 5 years[24]. The results of our study are in accordance with the findings of this published study.

However, drug-resistance was found to be the main obstacle in the benefit of antiviral therapy for the prevention of EV bleeding. All 3 LAM-resistant cases and 1 ADV-resistant case experienced bleeding. As a result, the efficacy of LAM in the prevention of EV bleeding decreased to a level that was not statistically different from that of the control group in the present study. The Kaplan-Meier curves of ETV, ADV and LAM crossed each other within the first 2 years, but deviated beyond the 2-year mark. It is known that drug resistance increases with time. A plausible explanation for this is that the high incidence of virological breakthrough observed with LAM reduced the efficacy of LAM in the prevention of esophageal bleeding. As studies have reported a lower rate of resistance for ETV[25], this agent may be a better choice in the prevention of esophageal bleeding in cirrhotic patients with active viral hepatitis B replication. The LAM/ADV combination has also been reported to have lower drug resistance rates[26]. However, combination therapy may be more expensive and result in more adverse events, and therefore, may not be well received by patients.

One limitation of the present study is that genetic screening for emergence of antiviral resistance was not performed. This is an important issue as current treatment guidelines recommend long-term treatment of patients with cirrhosis. Consequently, it is unknown whether the patients who experienced virological breakthrough also had emergence of genotypic resistance. In this study, the levels of HBV DNA, GOT, GPT and other biochemical parameters were tested in all patients at a 3-mo interval, however, only one case was found to have developed virological break through during routine examination. Although rescue treatment with additional ADV was administered immediately, the patient still experienced esophageal bleeding after a few weeks. In the other three patients who experienced bleeding, virological breakthrough had not been previously detected. As all four cases with virological breakthrough were compliant with the antiviral treatment, the most likely explanation for virological breakthrough is antiviral resistance. Investigations of the underlying gene mutations and switching to a more appropriate treatment regimen as early as possible may be useful in enhancing the effectiveness of antiviral therapy.

In conclusion, antiviral therapy with nucleoside analogs may delay progression of varices, decrease the risk of bleeding and improve liver function in patients with HBV-related cirrhosis and EV. However, drug resistance usually leads to bleeding in this special group of patients. Agents with a high rate of virological breakthrough may not be effective in the long-term prevention of esophageal variceal bleeding. The major limitation of the present study is the relatively small sample size of heterogeneous use of antiviral agents. These conclusions should be confirmed in further randomized controlled clinical studies.

Editorial assistance with preparation of the manuscript was provided by MediTech Media Asia Pacific Ltd (Shanghai, China).

Antiviral therapy with nucleoside analogs improves the clinical outcome of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. However, the emergence of resistance results in liver injury. The consequences may be worse in patients with esophageal varices (EV), in which bleeding and death often occur.

Recently, an on-line published study demonstrated that entecavir therapy reduced the risks of hepatic events in hepatitis B cirrhosis patients within 5 years. Koga et al reported an improvement in esophageal varices in patients following lamivudine (LAM) treatment in a retrospective study. However, the study only consisted of 12 patients treated with LAM and 6 controls, and there were no data on bleeding rate and the effect of virological breakthrough. As patients usually experience bleeding when virological breakthrough takes place, it is necessary to separate the patients and evaluate the harm of drug resistance and the benefit of HBV suppression in these patients to provide evidence-based treatment suggestions.

The present study evaluated the efficacy of antiviral treatment over 5 years in patients with HBV-related cirrhosis and EV, and found that antiviral therapy decreased the risk of bleeding; and agents with a high rate of virological breakthrough were ineffective in preventing bleeding. These findings for the first time provide evidence-based treatment suggestions for this special group of patients.

Antiviral therapy with nucleoside analogs may delay progression of varices, decrease the risk of bleeding and improve liver function in patients with HBV-related cirrhosis and EV. Agents with a high rate of virological breakthrough may not be effective in the long-term prevention of esophageal variceal bleeding.

Nucleoside analogs, are molecules that can inhibit HBV polymerase, and therefore decrease HBV load. They have been widely used in the treatment of hepatitis B. Virological breakthrough indicates that the viral load decreased to an undetectable level initially, and rebounded during follow-up. Virological breakthrough often leads to progressive liver injury and even severe liver failure.

The article provides statistical analysis of data from HBV patients who went through antiviral therapy to determine the role of antiviral therapy in esophageal varices and bleeding in HBV-related cirrhosis. This article provides information important to clinicians and HBV patients in general.

P- Reviewers Husa P, Liu ZW, Mir MA, Wong GLH S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Wang CH

| 1. | Fattovich G, Giustina G, Schalm SW, Hadziyannis S, Sanchez-Tapias J, Almasio P, Christensen E, Krogsgaard K, Degos F, Carneiro de Moura M. Occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma and decompensation in western European patients with cirrhosis type B. The EUROHEP Study Group on Hepatitis B Virus and Cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1995;21:77-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Realdi G, Fattovich G, Hadziyannis S, Schalm SW, Almasio P, Sanchez-Tapias J, Christensen E, Giustina G, Noventa F. Survival and prognostic factors in 366 patients with compensated cirrhosis type B: a multicenter study. The Investigators of the European Concerted Action on Viral Hepatitis (EUROHEP). J Hepatol. 1994;21:656-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shah V, Long KH. Modeling our way toward the optimal management of variceal hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1289-1290. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Carbonell N, Pauwels A, Serfaty L, Fourdan O, Lévy VG, Poupon R. Improved survival after variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis over the past two decades. Hepatology. 2004;40:652-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 568] [Cited by in RCA: 527] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yao FY, Terrault NA, Freise C, Maslow L, Bass NM. Lamivudine treatment is beneficial in patients with severely decompensated cirrhosis and actively replicating hepatitis B infection awaiting liver transplantation: a comparative study using a matched, untreated cohort. Hepatology. 2001;34:411-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hann HW, Fontana RJ, Wright T, Everson G, Baker A, Schiff ER, Riely C, Anschuetz G, Gardner SD, Brown N. A United States compassionate use study of lamivudine treatment in nontransplantation candidates with decompensated hepatitis B virus-related cirrhosis. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:49-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wright TL. Clinical trial results and treatment resistance with lamivudine in hepatitis B. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24 Suppl 1:31-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hadziyannis SJ, Tassopoulos NC, Heathcote EJ, Chang TT, Kitis G, Rizzetto M, Marcellin P, Lim SG, Goodman Z, Ma J. Long-term therapy with adefovir dipivoxil for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B for up to 5 years. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1743-1751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 674] [Cited by in RCA: 681] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Peters MG, Singer G, Howard T, Jacobsmeyer S, Xiong X, Gibbs CS, Lamy P, Murray A. Fulminant hepatic failure resulting from lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus in a renal transplant recipient: durable response after orthotopic liver transplantation on adefovir dipivoxil and hepatitis B immune globulin. Transplantation. 1999;68:1912-1914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Koga H, Ide T, Oho K, Kuwahara R, Hino T, Ogata K, Hisamochi A, Tanaka K, Kumashiro R, Toyonaga A. Lamivudine treatment-related morphological changes of esophageal varices in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatol Res. 2007;37:503-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Qureshi W, Adler DG, Davila R, Egan J, Hirota W, Leighton J, Rajan E, Zuckerman MJ, Fanelli R, Wheeler-Harbaugh J. ASGE Guideline: the role of endoscopy in the management of variceal hemorrhage, updated July 2005. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:651-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1229] [Cited by in RCA: 1209] [Article Influence: 67.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | de Franchis R. Evolving consensus in portal hypertension. Report of the Baveno IV consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2005;43:167-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 794] [Cited by in RCA: 733] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Japanese Association of Portal Hypertension. Criteria for record of endoscopic findings of esophagogastric varices. Kanzo. 1980;21:779-783. |

| 15. | Turnes J, Garcia-Pagan JC, Abraldes JG, Hernandez-Guerra M, Dell’Era A, Bosch J. Pharmacological reduction of portal pressure and long-term risk of first variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:506-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J, Grace ND, Burroughs AK, Planas R, Escorsell A, Garcia-Pagan JC, Patch D, Matloff DS. Beta-blockers to prevent gastroesophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2254-2261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 714] [Cited by in RCA: 653] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Woods KL, Qureshi WA. Long-term endoscopic management of variceal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1999;9:253-270. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Krige JE, Kotze UK, Bornman PC, Shaw JM, Klipin M. Variceal recurrence, rebleeding, and survival after endoscopic injection sclerotherapy in 287 alcoholic cirrhotic patients with bleeding esophageal varices. Ann Surg. 2006;244:764-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li CZ, Cheng LF, Wang ZQ, Gu Y. Attempt of photodynamic therapy on esophageal varices. Lasers Med Sci. 2009;24:167-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2125] [Cited by in RCA: 2171] [Article Influence: 135.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2323] [Cited by in RCA: 2401] [Article Influence: 184.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liaw YF, Leung N, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, Gane E, Han KH, Guan R, Lau GK, Locarnini S. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2008 update. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:263-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 666] [Cited by in RCA: 743] [Article Influence: 43.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, Schiff E, Han KH, Lai CL, Safadi R, Lee SS, Halota W, Goodman Z. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;52:886-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in RCA: 772] [Article Influence: 51.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wong GL, Chan HL, Mak CH, Lee SK, Ip ZM, Lam AT, Iu HW, Leung JM, Lai JW, Lo AO. Entecavir treatment reduces hepatic events and deaths in chronic hepatitis B patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2013;[Epub ahead of print]. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 347] [Cited by in RCA: 396] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, Pokornowski KA, Eggers BJ, Fang J, Wichroski MJ, Xu D, Yang J, Wilber RB. Long-term monitoring shows hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naïve patients is rare through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1503-1514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 615] [Cited by in RCA: 633] [Article Influence: 39.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yun TJ, Jung JY, Kim CH, Um SH, An H, Seo YS, Kim JD, Yim HJ, Keum B, Kim YS. Treatment strategies using adefovir dipivoxil for individuals with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6987-6995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |